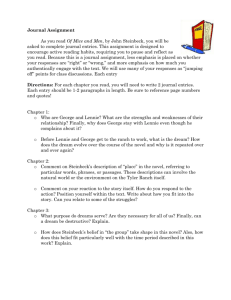

Of Mice and Men - sparknotes 03.doc - 11ENG-HT

advertisement