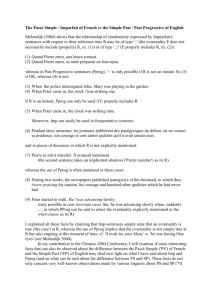

Des gares réelles aux gares fictives : bref panorama de 1890 à 1930

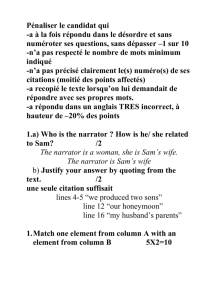

advertisement