Handmaid`s Tale, The

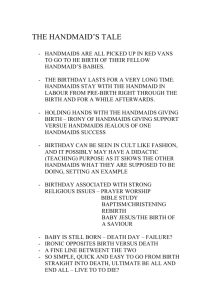

advertisement

Handmaid's Tale, The By MARGARET ATWOOD 1986 Author: Margaret Atwood Characters As in her previous novels, Atwood has chosen a first-person female narrator for the story of the plight of a state "handmaid" reduced to a strictly biological destiny. The reader knows the narrator only as "Offred," in keeping with the Gileadean practice of renaming handmaids as the property of whichever commander they serve at the time (hence "Offred" literally means "of Fred"). Like other Atwood protagonists, Offred begins her narration in a state of psychic numbness, determined to keep from thinking about the nightmarish circumstances of her life. Having become a handmaid following a failed attempt to escape across the Canadian border with her husband and child (the former presumably now dead and the latter placed in an adoptive home with politically correct parents), Offred rejects the premises of the new order but attempts to comply with her captors' agenda. In her passivity, she serves as another of Atwood's studies in the psychology of victimization, and her slow renunciation of that stance creates the novel's central drama. In the course of the narrative she shows a growing willingness to risk rebellion on both emotional and political levels, despite the threat to her oft-voiced goal of survival. Offred cannot repudiate her emotional history, nor can she escape the tacit complicity of her generation in failing to challenge the patriarchal backlash against women's growing autonomy in the late twentieth century. But Offred also reveals herself to be an intelligent and reflective woman possessed of an ironic wit. She wryly traces the odd alignments of left- and right-wing politics that made possible the oppressively intolerant Gilead. Ironically, the fundamentalist revolution has coopted the feminist ideal of a female-centered "women's culture" to serve patriarchy's ends. Offred is well aware that less compliant women offer alternatives to her own acquiescence. For example, her radical feminist mother (under whose rhetorical intensity she had often chafed "back there") is now condemned to a colony for "unwomen." Her college roommate Moira so aggressively resisted her assignment as a handmaid that, following torture, she has been posted to a high-class brothel, her sexual servitude mitigated by the freedom to live out her lesbian identity in "off hours." Finally, Offred personally witnesses the self-sacrifice of Ofglen, a handmaid whose participation in the Mayday Underground demonstrates the fatal lengths to which some women still go to resist Gilead's oppression. Among the other factors that undermine Offred's fearful passivity is her Commander's restiveness within the desexualized culture he ostensibly upholds. Trading on his privilege, he recklessly seeks out Offred for "illicit" rendezvous where he provides her with "forbidden" relics of the past such as women's magazines and scrabble games, both of which violate Gilead's laws against female literacy. Susceptible to the predictable Achilles' heel of sexual appetite, the Commander gives Offred a renewed sense of female power, however problematical its terms. He even brings her to a brothel where the full measure of Gilead's hypocritical efforts to destroy unsanctioned (that is, nonreproductive) sexuality are exposed. The marked bitterness of the most privileged females in Gilead, the Commanders' wives, further dramatizes the kingdom's shaky foundations. Serena Joy, Fred's wife, nationally prominent before the revolution as a Christian fundamentalist advocate of traditional gender roles, has succeeded so well in furthering her cause that she now finds herself relegated to the sidelines; her outrage at her own impotence rips through the idealized facade of her supposedly perfect life. Disabled by arthritis, her crippled condition be-speaks her emotional alienation. Unable to bear her own children, she is subjected to the humiliating necessity of employing a handmaid, whose copulating episodes with her husband she must grimly assist. Like Fred, she proves willing to subvert the prescribed order by arranging a secret affair between Offred and the Commander's chauffeur Nick, justifying this "treason" as a more practical route to pregnancy than reliance on the probably sterile Fred and thus a necessary move to ensure Offred's survival. But her discovery of the Commander's liaisons with his handmaid unleashes her full vindictiveness toward Offred, although she is not the agent who apparently betrays Offred to the authorities. The narrative climaxes with the arrival of a police van which takes the handmaid away as a gender traitor. In fact, through her lover's participation in the Underground, the possibly pregnant Offred is in fact rescued from the sure death that otherwise awaits her at the hands of Serena. Nick's role in the novel is an ambiguous one. Although a male, he lacks the status of more powerful men like the Commander, indicating that other stratifications besides that of gender sustain Gilead's hierarchy. Forbidden to desire the women around whom he works, he too is victimized by the restrictive sexual gospel of the kingdom. Nonetheless, as a measure of their shared rebel impulses, he and Offred enter into a love affair that is simultaneously comforting, exhilarating, and dangerous. Some feminist critics regard Offred's infatuation with Nick as regressive, throwing her back into heterosexual thrall at the very time she should be moving toward greater autonomy and more overtly politicized behavior; others see it as a crucial step in her evolving recovery of self as well as a reaffirmation of the potential for healing male/female bonds beyond the power abuses of patriarchy. The outcome of the relationship approximates a fairy tale denied its happy ending. Nick rescues Offred and acts for her when she proves incapable of acting to save herself. He makes it possible for her to go into hiding; there, perhaps pregnant with Nick's child, she finds time enough to compose the audio tapes that provide historians with the raw material that becomes this "tale" of Gilead. Offred's own destiny beyond the history recorded on those tapes remains a mystery, however. Social Concerns The Handmaid's Tale gives heightened, prophetic urgency to a number of Atwood's long-standing social preoccupations. The novel is set in a futuristic society called the Republic of Gilead, a new nation resulting from a fundamentalist coup in what was once the northern United States. The action occurs in Boston and explicitly recalls Puritan New England, earlier site of a community insistently pursuing a single-minded messianic agenda. (The Canadian Atwood herself has New England ancestors, one of whom was tried as a witch and survived hanging; the novel is dedicated to her, as well as to Harvard scholar Perry Miller, with whom she once studied). Like its historical antecedent, Gilead is a theocracy whose legal, political, and ethical strictures rest upon conservative interpretations of the Bible cannily used to legitimize a patriarchy of elite white males who repress the majority of the population through overtly racist and sexist policies. The inequities of this society are shown to be intimately related to a number of other catastrophes that have ravaged Gilead. In earlier works Atwood had identified the United States as the locus of a dehumanizing capitalistic and technocratic ethos which wages war on nature. Gilead dramatizes the inevitable ecological disasters attendant upon such practices. Nuclear accidents, toxic pollution, virulent new diseases, and the chemical mistreatment of their own bodies have so reduced the fertility rate among whites that the chances of bringing a healthy new baby into the world are now one in four. The schism dividing humans from the ravaged natural world only intensifies human predatoriness and produces a society whose paranoid isolationism propels it into a perpetual state of war against subversive citizens and supposedly hostile neighbor states. War becomes a state of mind justifying a pervasive militarism with its attendant drain on national resources; as such, it reinforces the patriarchal hierarchies that undergird the culture. Gilead bases this social vision on a religious ideology which sanctions its power politics as God's will; the world of this novel is shown to be a logical, if exaggerated, expression of the chauvinistic self-righteousness with which Americans have historically exercised their raw might around the world. Atwood's indictment of modernity's technocratic assault on nature complements an equally unyielding portrait of a decadent mass culture whose consumer fetishism, narcissism, and cultural debasement produces postmodern anarchy and spawns the drastic anti-dote of a Gilead. As with all dystopias, The Handmaid's Tale identifies the seeds of its futuristic nightmare in the excesses of the present and suggests the ease with which those excesses can trigger a violent backlash annihilating the cherished freedoms of the culture it is ostensibly trying to save. Atwood's treatment of contemporary culture is more ambivalent here than in earlier works, however. Although she is clearly repulsed by its pervasive corruption of individual sensibility, she cautions against simplistic efforts to repress its most revolting elements. She thus raises the troubling question: What degree of liberty can a democratic society safely exchange for cultural stability? Themes By making her protagonist a woman of child-bearing age, Atwood foregrounds gender as the central dichotomizing agent within Gilead, illuminating the degree to which misogynist hostility toward female sexuality and envy of women's procreative capacities can lead to their systematic subordination. Atwood creates a nightmarish society which forbids women virtually all access to power, be it financial, educational, political, or familial. At its inception Gilead denies women money and credit, eliminates their jobs, and outlaws female literacy. Later policies group women into segregated categories: Handmaids, whose apparent fertility has been commandeered by the state to "breed" offspring for childless white male Commanders and their wives; Aunts, who serve as the government's indoctrination agents of other women; Marthas, whose function is that of asexual workers in the homes of the elite; Econowives, who marry lower-echelon males and serve in multiple capacities as wives, mothers, and laborers; and Unwomen, whose "unfitness" politically or biologically has relegated them to certain death cleaning up toxic waste sites. Such stratifications pit the women of different groups against one another, illustrating an important component of Gilead's systematic misogyny: the exploitation of hostilities women direct against one another. While such tensions are frequently the result of the power structures that control their lives, the women of Gilead operate in complicity with them by fomenting divisive grievances and distrust among themselves. This in turn thwarts any collective effort by women as a group to resist their institutional helplessness. Animosities among women had permeated the pre-Gilead world as well, polarizing them into opposing camps championing antithetical notions of female possibility. Despite their mutual intolerance, their shared essentialism about women's "nature" and their respective campaigns against the worsening dangers for women in post-industrial economies unwittingly combined to facilitate Gilead's revolution and its reimposition of strict gender roles. There is a grimly ironic link between the women-led protests of escalating violence in pre-Gilead America and the seductive promise of the new society to make life "safe" again for women. The price of moving, as one of the Aunts puts it, from "freedom to" to "freedom from" is nothing less than women's hard-won autonomy. Techniques In The Handmaid's Tale Atwood again uses her trademark Gothicism to convey the grotesque dislocations produced by Gilead's social agenda. The hallucinatory imagery filling Offred's narration, usually Atwood's way of revealing the intense psychic alienation of her protagonists, here derives from horrific governmental policies made all the more haunting by Offred's matter-of-fact delivery. Harvard Yard has been turned into a public torture and execution area, with the bodies of "gender traitors" such as homosexuals, rapists, adulterers, and abortionists regularly displayed as evidence of the fate awaiting the unorthodox. Women participate in violent group assaults called "particicutions," in which supposed criminals are literally ripped to shreds by frenzied female mobs. Gilead's extensive behavioral rules eerily contribute to the ominous climate surrounding women. The red robes and white blinders the handmaids wear, as well as the demure and silent pairings in which they travel in public, offer only two examples of how Atwood builds the disorienting atmosphere of the novel. Offred's first-person interior monologue intensifies the reader's experience of the claustrophobic entrapment women suffer in Gilead. A familiar narrative device in Atwood's fiction, here it receives two compelling twists, both revealed at the novel's conclusion. One is the sudden opening out of the text from its Gileadean milieu to a futuristic frame of reference set in 2195, some two hundred years after the events just described. This epilogue is presented as "a partial transcript" of a yearly conference of academics engaged in the study of Gilead, now a defunct society primarily of interest to antiquarians. Such a transition releases readers from the suffocating confinement of Offred's consciousness and offers the reassurance that the historical nightmare recorded in the text proper has ended. The intertextual complexity generated by the tonal layerings of the epilogue qualifies such effects, however. Atwood presents the scholarly conference satirically, not only exposing the reductive treatment being given Offred's riveting story but raising provocative doubts about just how much of Gilead's patriarchal repression has in fact passed away. While women and men function as seeming equals within this academic community, the female chair of the conference busily orchestrates the social niceties of the occasion as back-drop to the remarks of the male speaker, Professor James Darcy Pieixoto. The professor reveals a penchant for sexist humor and evinces far greater interest in discovering the identity of the Commander than in Offred's own story. Pieixoto also reveals the other narrative "trick" at work in the text: the news that Offred's voice has survived, not as a written document, but as a series of tape-recordings made after her escape from Boston. Just as the recovery of women's history is often dependent upon nonliterary and oral forms, Offred's tapes speak across centuries of a woman's hunger to reclaim and validate her life. Yet the narrative composed from her tapes is the work of an insensitive male and his faceless assistants who have become interpretive mediators intruding between the reader and the speaker. The professor entitles their text The Handmaid's Tale—not only a selfconscious homage to Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales but a smirking sexual distortion of the great poet's original language. To Pieixoto's final comment, "Are there any questions?" one is prompted to ask, in true postmodern perplexity, just whose story exists within these pages after all. Literary Precedents Much has been made of Atwood's obvious indebtedness to the tradition of dystopian fiction preceding The Handmaid's Tale, most notably George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-four (1949) and Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932). Atwood's work is antiutopian in its concern with the power constructions whereby ideologically driven regimes establish and maintain their dominance over select populations. She uses differentiations based on gender, race and class to imagine a rigidly hierarchical society whose absolutist cultural values, permitting no compromise, foster brutal persecution of "deviance." Dystopian fictions are cautionary tales that warn against what their authors view as society's most dangerous existing tendencies. The nightmarish ambiance born of the genre's characteristic extremism saturates The Handmaid's Tale, whose alien philosophical and political foundation rests paradoxically upon enough familiar detail to make it jarringly immediate. Atwood claims that every abuse and horror of Gilead social policy has either been practiced at one time in history or has a direct parallel in the contemporary world. She has been faulted by some critics for not having imagined as self-enclosed and original a new society as exists in Nineteen Eighty-four but Atwood argues that Gilead is intended as a relatively recent historical development without the temporal leap into the future that characterizes other such fictions. She also eschews labeling the novel science fiction, preferring to call it "speculative fiction." In comparison to this dystopian element, very little attention has been paid to the tradition of feminist Utopian writing with which The Handmaid's Tale is also in dialogue. Unlike Charlotte Perkins Gilman's Herland or Marge Piercy's more recent Woman on the Edge of Time (1976), both of which present idealized communities where hierarchical gender polarizations and the conflicts they produce are replaced by virtues associated with female culture such as nurturance and egalitarianism, Atwood's novel posits a dark alternative where female subservience is the central fact of society. Related Titles Earlier in the decade that produced The Handmaid's Tale, Atwood published Bodily Harm (1981), a novel whose protagonist, a Toronto journalist named Rennie Wilford, decides to flee the site of a recent mastectomy and her resultant sense of deformation for the sunnier climes of the Caribbean, which she plans to make the subject of a glib travel piece. Instead, she is exposed to raw political tyranny as she finds herself unwittingly caught up in the stuff of an international thriller even though her point of view on the action remains decidedly marginal and uninformed. Bodily Harm, then, offers a political primer on the fusion of gender and nationalism within the structures of patriarchy that Atwood expands so dramatically in The Handmaid's Tale. In Rennie she creates a woman who, like Offred, has been lulled by her relative privilege to believe herself immune from the abuses visited on the powerless, only to find "She is not exempt. Nobody is exempt from anything." She too is imprisoned and must move beyond her conditioned feminine acceptance of the victim's role to discover avenues of active resistance and moral empowerment. And as a writer, she recognizes that her most subversive talent lies in telling honestly what has happened. Whether she actually escapes to achieve her goal remains as mysterious as Offred's ultimate fate. Adaptations The immense popularity of The Handmaid's Tale and its provocative themes led to its translation to the screen in 1990. Considerable international filmmaking talent was involved in completion of the project: German filmmaker Volker Schlondorff directed (best known in the U.S. for The Tin Drum, 1980, and the 1985 TV version of Death of a Saleman); playwright Harold Pinter wrote the screenplay; high profile Hollywood stars Robert Duvall (as the Commander) and Faye Dunaway (Serena Joy) joined Victoria Tennant (Aunt Lydia), Aidan Quinn (Nick), Elizabeth McGovern (Moira), and Natasha Richardson (Kate/Offred) in the cast; Daniel Wilson produced the $13 million project for Cinecom. The film was marketed and reviewed extensively, and premiered at the Berlin Film Festival in the city where Atwood says she began writing the novel in 1984, but it received mixed critical response. The structural complexity of the novel was sacrificed to create a chronological staging of events leading to a far more conventionally heroic and less ambiguous ending; Offred was given the pre-Gilead name Kate and was made more active in her own behalf; the love story was showcased at the expense of the novel's ideological critique (no doubt a result of the difficulty Wilson had in raising money for the project given its themes, particularly its feminism). The screenplay, albeit satisfactory to Atwood herself, necessarily abandoned the interiority of the novel, created by Offred's ongoing monologue, and instead opened out the action to give visual immediacy to the peculiar mores of daily Gilead society. Schlondorff, at first reluctant to undertake the project, finally accepted when he began envisioning the work "from a Kafka angle rather than as a political prophecy." The acting is strong and the cold precise beauty of the screen imagery successfully conveys the paradoxical familiarity and strangeness that account for the terror aroused by this brave new world. Richardson is too young and nubile to convey Offred's precarious circumstance as a handmaid near the end of her fertility, but she does capture Offred's tentativeness. Duvall effectively blends the banal and the sinister in portraying the Commander; Dunaway aptly depicts the brittle surfaces and barely suppressed rage of Serena Joy. But while the film is unsettling, it lacks the emotional or intellectual impact of the novel. Ideas for Group Discussions No other Atwood fiction has aroused the public debate that has accompanied The Handmaid's Tale, and thus it should provoke lively discussion in any group undertaking to read it. The most obvious focus for attention should be its provocative thesis that religious conservativism around the world threatens to reverse the gains of the contemporary Women's Movement and create a nightmarish subordination of women to a reinvigorated patriarchy. Similarly, readers should examine Atwood's underlying assumption that the oppression of women has some of its most tenacious roots in theology; while her most obvious target is the West's Judeo-Christian tradition, she also incorporates elements from Islam and Hinduism, among other religions. Readers might consider Atwood's claim that there is no political circumstance in the text that she cannot document as having occurred at some point in the historical past or present—it is worth contemplating the impact of so many such practices brought together in one social system. For those familiar with other famous dystopias, a brief comparison with Huxley's Brave New World or Orwell's 1984 might help to clarify the assumptions informing Atwood's imaginary realm and determine where she agrees with her predecessors' premises and where she sets forth premises unique to her own vision of ideologically driven totalitarianism. Another equally controversial facet of Atwood's analysis involves her criticism of the censoring impulses being unleashed by abuses of public expression and eruptions of violence in free societies around the world. The novel asks readers to consider the price of freedom and the potential consequences of circumscribing what can and cannot be said or thought. Atwood is just as uncompromising with feminists as with fundamentalists on this subject, and she lampoons those in both camps who argue for a monolithic imposition of their ideology for the "good" of human society; it is worth asking, then, in what ways political idealisms at any point on the spectrum fall into the trap of absolutism and intolerance. The novel's evocation of ecological apocalypse invites discussion about the plausibility of its nightmare scenario and the relationships Atwood draws among consumerism, militarism, and natural catastrophe. Her placement of infertility at the center of this crisis offers a cunning point of intersection between legal, religious and scientific arguments about human behavior and could provoke lively debate about alternative scenarios dealing with the inability of humans to procreate—including ones already surfacing in contemporary culture such as surrogate motherhood and in vitro fertilization. Why are women the special targets of the new social order devised in Gilead? What other special targets exist, and why? Why do race and gender hierarchies matter so much to the ruling elite of this world? How does class stratification blur and reinforce the other categories of differentiation in Gilead? Why are class designations so important to the workings of this society? How are those in the lower social rungs kept there? Atwood's fictions are routinely set in Canada and involve Canadian characters, but this one is situated squarely in the U.S. Does her critique of what she once called "Americanism" continue in such a choice? What does she seem to consider distinctively American about Gilead and the historical and cultural processes that have brought it into being? Why does religion stand at the center of the backlash Atwood imagines against women's liberation in the late twentieth century? What premises about women does it permit, and what kind of action on those premises does it encourage? Why? What is Offred's world view and how does it shape her behavior in the years before the revolution? What is she like at the start of the novel when she is introduced as a "handmaid?" How does her attitude about her situation change in the course of the narrative? What prompts those changes, and where do they lead? What do the relationships among women both before and after the revolution suggest about women's responsibility for the nightmare that has overtaken them? How are those tensions exploited and institutionalized in Gilead to ensure that women will not organize to change their circumstances? What role does Offred's mother play in her daughter's imaginative life? How does she represent the Women's Movement of an earlier era? In what ways is she satirized? In what ways is she vindicated? How might Moira be seen as an extension of the older woman—and how is she distinctly different? How does the relationship between the Commander and his wife Serena Joy illustrate the nature of gendered relationships in Gilead? Are they a happy couple? What fissures exist between them, and what opportunity for redress does the state provide? Consider the Puritan implications of the novel's New England setting. What is "Puritanical" about the elites' perspective on sexuality? What promises are made to women about the ways the kingdom will safeguard their sexual dignity? How does the sanctioned emphasis upon procreativity backfire against women and men both? What is suggested about the ability of any political system to control the sexual energies of human beings? What is the Commander like? Is he in any way surprising, given his position among the elite? In what ways is he also a cliche of male tendencies? What does he want from Offred? What does it matter that we know of others he has attempted to possess in the same way? The concept of "gender traitor" rests upon very definite notions of what constitutes "proper" masculinity and femininity in Gilead. In what ways can women be gender traitors? Men? Why is homosexuality a particular target in this regard? What kind of relationship does Offred have with her husband before the revolution? How does political upheaval change it? What becomes of her family in the revolution's after-math? How might that earlier relationship compare with the one Offred develops later with Nick? What does the latter suggest about the potential of heterosexual bonding beyond Gilead? Why does "telling" this story become so important to the novel's themes about women's voice and its fate under patriarchies like Gilead? Why does it matter that we have actually been "listening" to tapes Offred composed after her escape? What does it mean that we are denied the satisfaction of knowing what happened to her? What does the final framing device of the novel add to our experience of reading this story? What is the effect of the narrative's projecting us beyond the life of Gilead itself to a time far in the future? Why put Offred's tapes in the hands of academics who seem only interested in their antiquarian value? Is the work of feminism really done? Barbara Kitt Seidman Linfield Colleg