Outline of Exhibit Panels (By Natalie Goodwin)

advertisement

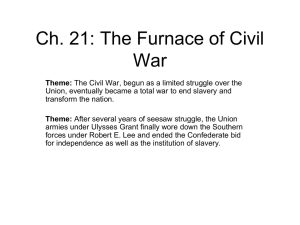

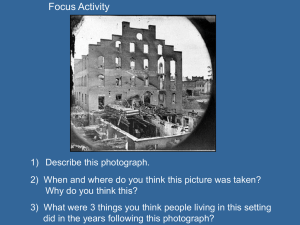

“This Cruel War: The Civil War in Rutherford County” Exhibit Outline Introduction The Civil War transformed the lives of every man, woman, and child in Rutherford County, one of the most contested regions during the war. Bringing heartbreaking losses and financial ruin for many local citizens, it also led to freedom from enslavement. The region’s role as the breadbasket of the Union Army, and the strategic gateway to the Deep South brought the full wrath of the war upon local residents. Despite the brutality and hardships, the Civil War left important legacies that continue to influence the region to this day. Prelude to War (1860-1861) Photos: Graphic—graph* Image—slaves in corn field Image—slave with cotton sack Map—Slavery in TN Map—Southern states map from Dec. 1863 (Harpers’)* Photo—Alice Ready Photo—James M. Haynes Main Panel label: On the eve of the secession crisis in 1860, Rutherford County resembled other Middle Tennessee counties with its thriving agrarian society populated by a mix of enslaved workers, small farmers, planters, merchants, and free people of color. This blend of economic and social interests created a dynamic political culture that favored Unionism until June 1861, when most county voters chose to secede from the Union. Rutherford County citizens could not have predicted that within a few months they would be living in occupied territory. Group label: In the decades prior to 1860, Rutherford County evolved from a frontier landscape to a thriving agrarian society populated by a dynamic mix of economic and social classes. The enslaved population was the fastest growing portion of county residents, increasing from 26% to 47% of the population from 1820 to 1860. Even though slavery provided economic and political power to many local families, they remained bitterly divided on the issue of secession. Group label: Unionists and Secessionists In the 1860 presidential election, the Rutherford County electorate signaled its preference for staying in the Union by voting for John Bell, the candidate for the Constitutional Union Party. Likewise in a referendum in February 1861, after Deep South states had seceded from the Union in response to Abraham Lincoln’s election, the county’s voters chose again to reject secession. After Lincoln’s call for 75,000 troops in response to the attack on Fort Sumter, however, local opinions shifted dramatically. In a June 1861 referendum spoiled by widespread voter intimidation, Rutherford County voters chose to join the Confederacy by a vote of 2,392 to 73. Quotes: “At the time of the election the feelings of the community had been worked up to a fever heat . . . I was known as an outspoken Union man. I lived within about a mile of the polls. Threats were made that if I did not go to the polls and vote for ratification I would be killed.” John J. Neely, farmer and schoolteacher “I was told that no Union man would be allowed to vote . . . I did not know but I might have trouble and therefore took my gun with me to the polls. At the door of the house where the election was being held I met one of my neighbors, a strong secessionist, and he said to me: ‘Joe how are you going to vote?’ I said ‘I am going to vote as I damned well please.’ I voted against ratification.” Joseph R. Thompson, farmer and distiller "All excited and aroused. All united. Secession flag waves over us. All for war." Telegraph from Murfreesboro to Nashville, June 1861 Sidebar: James M. Haynes James M. Haynes was a Unionist in Rutherford County. On June 8, 1861, when he arrived to vote in the second secession referendum, he declared he was “opposed to the cause of rebellion and secession,” and a “very intense feeling was expressed” against him by several angry men. Feeling that he was in danger, he claims he voted against his convictions explaining, “I can vote with you but my feelings are not with you.” Sidebar: Alice Ready Alice Ready was the staunch pro-Confederate daughter of Charles Ready Jr. and his wife Martha Strong Ready. Early in the war, she recorded in her journal that “for the sake of liberty and independence . . . our cause is just and righteous." After Union troops occupied Murfreesboro, it shook her faith in the Confederacy. “Can it be possible that this revolution . . . will result in merely a grand rebellion! God forbid.” Her father’s arrest for secessionist sympathies and her sister’s marriage to famed Confederate cavalry leader John Hunt Morgan strengthened her resolve. War Comes to Rutherford County (1861-1862) Timeline (on one panel; there may be an additional timeline on the GIS panel) Photos: Murfreesboro (1863), Battle of Stones River (1863) Murfreesboro Armory Rifle—refurbished “Tennessee Rifle” William Ledbetter, Sr. William Ledbetter Jr. Bettie Ridley Blackmore “War in the Border States”—Harper’s Weekly image Nathan Bedford Forrest Newspaper headline of Forrest’s Raid* John Beatty Union Occupation (Image: War in the Border States Harper's 1863) Forrest Raid: (Image 3: signpost; Image 5: Murfreesboro News Gore Center, Pittard) Morgan-Ready wedding (Image 2: signpost Gore Center, Pittard Main Panel Label: Rutherford County’s residents never imagined the war would come to their communities. In the initial zeal of the war, local leaders supported the Confederate cause in numerous ways, including offering material support and raising at least six local divisions of soldiers for the Confederate Army. However, when the Union Army arrived in midMarch 1862, citizens of Rutherford County found themselves under the control of a hostile occupying force. Slavery immediately began to break down, and white families were subjected to foraging in their fields, inspections, and arrests. Although a raid by General Forrest in July of 1862 temporarily pushed Union forces out of the county, the Confederate loss at the Battle of Stones River later that year brought the county back under Union control. Group Label: The war resulted in starvation and destruction of property for many residents of Rutherford County. They also began losing their slaves, as the slaves ran away to Union camps, or were confiscated by Union soldiers. In an effort to have all supplies necessary to fight the war, the Union and the Confederacy both did their share of raiding homes and taking possession of residents' food, animals, and property. Food shortages and high prices also made life difficult. Fear and loss gripped at residents as they struggled to make ends meet, and tried to survive the destruction around them. Quotes "But alas! The change! Everything beautiful and comfortable seems to have passed away. From Nashville to Murfreesboro the devastation of homes and farms is complete” Nashville Daily Union, February 15, 1863 “Well when they started off fightin’ at Murfreesboro, it was a continual roar . . . It sounded like the judgment. Nobody felt good. Both sides foraging’ one as bad as the other, hungry, gettin’ everything you put away to live on. That’s ‘war’. I found out all about what it was. Lady it ain’t nothin’ but hell on this earth.” Hammet Dell, WPA Slave Narrative “(General Mitchell) made a little speech on the square, and said that insults to the soldiers would be summarily punished, if the citizens were controlled he should control his soldiers, if not he would have no desire to do so.” Alice Ready Diary, March 19, 1962 “You have but little idea of the privations that “secesh” has brought upon this “glorious Confederacy.” No sugar, no tea, no coffee, no soda, no salt, no kind of cloth but what is made by hand.” Jane C. Warren to Electa Ames, August 27, 1863 Sidebar: William Ledbetter Sr. and the Murfreesboro Armory In 1861 and early 1862, William Ledbetter Sr. operated a Confederate armory in Murfreesboro that produced several hundred new rifles and refurbished over three hundred older flintlock rifles for combat. As one Confederate officer reported, the Murfreesboro Armory “made a very good gun.” The arrival of Union troops in March 1862 forced the armory to close. Sidebar: John Beatty John Beatty was raised in Ohio, joined the 3rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry in 1861, and fought at Stones River. He was part of the occupation of Murfreesboro from January to June 1863, and rose from Lieutenant Colonel to General. He later became a US congressman and banker. In his memoirs, he recalled the devastation that the residents faced. He stated, "Riding by a farmhouse this afternoon, I caught a glimpse of Miss Harris, of Lavergne, at the window and stopped to talk with her for a minute. The young lady and her mother have experienced a great deal of trouble recently. They were shelled out of Lavergne three times, two of the shells passing through her mother’s house. She claims to have been shot at once by a soldier of the One Hundred and Nineteenth Illinois, the ball splintering the window sill near her head. Her mother’s house has been converted into a hospital and the clothes of the family taken for bandages. She is therefore more rebellious now than ever. She is getting her rights, poor girl.” Occupation (1863) Photos: Image: 15: Guerilla War Harper's 1863 Foraging/raids (Image: 13 Foraging raid for food, livestock, and contraband labor Harper's 1863; Image 9:Army beef Harper's 1863) Murfreesboro Square (1864) Bettie Ridley Blackmore Fortress Rosecrans image Fortress Rosecrans map Gen. William S. Rosecrans Women working as nurses in hospitals—Harpers Fort Rosecrans (Image 11: Rosecrans Gore Center, Pittard; Image: 3 Fort Rosecrans CDV) Image: “When this Cruel War is Over” song and image (1862) Main Panel Label: After the Battle of Stones River, the residents of Rutherford County endured traumatic times as they coped with thousands of dead and wounded soldiers and the physical devastation of the battle. As Confederate forces moved southward, thousands of Union troops moved in for a long-term occupation of the county, then continued until after the war ended in 1865. Enslaved Africans on the county’s farms and plantations flocked to the Union camps for protection and employment as they grasped the opportunity for freedom. Nevertheless, all local residents suffered from severe food shortages, foraging raids, and lawlessness in the countryside. Group Label: After the battle of Stone's River, Union General William Rosecrans and his troop constructed Fortress Rosecrans to serve as a supply depot. The fortress was used to store arms, food, and equipment for the Union troops. Fortress Rosecrans was the staging ground for the campaign to the Chattanooga March to the Sea. Group Label: As the war went on around them, residents witnessed the horrors of death and destruction. Hospitals were set up to take care of the injured and dying soldiers, but the injured soldiers, both Union and confederate, were too many to care for. In a letter written to Margaret Blair in January 1863, W.W. Blair, a doctor from Ohio who worked as a Union surgeon in the field hospital in Rutherford County, described the war as "terrible beyond description." War was something that residents had never had to deal with, yet they quickly became a part of the death and destruction. Quotes: “Murfreesboro is one vast hospital, nearly every house having more or less wounded in it, the farm-houses for miles along the various roads are also used for the same purpose.” Nashville Daily Union, January 9, 1863 ‘There are many fine residences in Murfreesboro and vicinity; but the trees and shrubbery, which contributed in a great degree to their beauty and comfort, have been cut or trampled down and destroyed. Many frame houses, and very good ones too, have been torn down, and the lumber and timber used in the construction of hospitals.” John Beatty Memoir, April 5, 1863 “Crowds of insolent Yankees came daily to our house for forage, chickens, horses, meat and everything else they chose to demand.” Journal of Bettie Ridley Blackmore, Winter 1963 Sidebar: Bettie Ridley Blackmore Blackmore was the daughter of a prominent pro-Confederate family living near Jefferson. After her husband left to fight for the Confederacy, she contracted tuberculosis and never fully recovered. Her journal recounts how Union soldiers frequently harassed her and her mother, including twice burning down their home in the middle of the night. Sidebar: Jabez Cox Cox was a Quaker who enlisted as a private in the 133rd Indiana Infantry. Stationed at Murfreesboro from May to August 1864, he kept a diary that captured his thoughts about the problems facing Rutherford County during this time He commented that before the war “the inhabitants of the surrounding mansions were enjoying liberty, peace and prosperity, but alas how many by their own hand have brought ruin on their homes.” After the war, he became a lawyer and a judge in Indiana, and his son, Edward Everett Cox, emerged as a prominent journalist. What Would You Have Done? During the occupation of Rutherford County, it was common for the Union army to raid the homes of local residents and take whatever property they felt would be of their own personal use. If Union soldiers came to your home and told you they were going to take your property from you, what would you have done? Divided Loyalties Photos: Spies/Scouts (Image 16: Hanging Spies in Tennessee Harper's 1863) Morgan-Ready Marriage Thomas Hord Loyalty Oath Main Panel Label: Throughout the war, constantly shifting circumstances made loyalty a difficult issue to determine. From the Union Army’s perspective, loyalty was a matter of security for their troops. They demanded signed loyalty oaths from anyone who wanted to conduct business or to receive a pass to leave town. From the point of view of Confederate sympathizers, loyalty to their cause was a sacred burden. Townspeople were often shocked to hear that friends, family and neighbors had signed an oath of loyalty, and slaveholders were often dismayed to find that their slaves were not loyal to them. At the same time, some citizens, including women, began working as spies for the Confederate cause. Group Label: Loyalty was an important issue that affected how citizens lived their daily lives. In many instances, citizens had to take a loyalty oath before they could conduct business; and in some cases, the oath wasn't enough to keep Union soldiers from taking property. Group Label: Women were also active in the Civil War, and they demonstrated their divided loyalties by either acting as spies for their side, or marrying 'the enemy'. Sophia Lytle Harrison turned in her stepson to the Union army in an effort to gain favor with the Union, and later married a Union captain. On the other hand, Mary Kate Patterson acted as a spy for the Confederate army. Quotes: “And the reins of military despotism are gradually being drawn tighter, still tighter around the people of Murfreesboro. . . no one can go two miles from town . . . without taking the oath of allegiance to the United States.” Alice Ready Diary, April 8, 1862 “I think the southern men had better be turning their heads towards home, many of their wives are getting pretty fast with Yank beaux.” Letter from Martha Ready to Martha Morgan, April 8, 1865 “The people of Tennessee are ready & anxious to embrace the offer of pardon and take and keep the oath (of loyalty) prescribed in good faith, but they have not the opportunity. There is no officer in the state authorized to administer the oath and register it.” Edwin Ewing to Abraham Lincoln, January 23, 1864 Sidebar: Emma Lane Emma Lane was 16 when she began writing in her diary about the war. In the diary, she discusses the capture of a Confederate Spy. "I saw an account of the execution of a friend he was a Confederate soldier and was caught in the Federal lines acting as a spy. What a horrible fate! What a shock it will be to his old Father. O, when will this cruel, cruel war cease, this war which has caused the separation of friends, which has brought trouble sorrow & desolations to the hearthstones of so many." January 25, 1864 Sidebar: Mary Kate Patterson From 1862 to 1865, Mary Kate Patterson was an active Confederate spy who lived near Lavergne. She befriended occupying Union troops to obtain passes to Nashville, where she secretly secured supplies and messages to smuggle in the false bottom of her buggy. Her family also sheltered Confederate soldiers in their home. After Union forces executed family friend Sam Davis in 1864, Patterson traveled to Pulaski to identify the body; she later married Sam's brother John Davis. Upon her death in 1931, she became the first woman buried in the Confederate Circle in Nashville's Mt. Olivet Cemetery. Sidebar: Thomas Hord Hord was an anti-secessionist who was one of sixty-five businessmen who took the loyalty oath to operate businesses in Murfreesboro. Nonetheless, Union soldiers repeatedly ravaged his “Elmwood” plantation because of its proximity to the Stones River battlefield. After the war, he submitted claims in damages to the U.S. government that totaled $59,124.60 (equivalent to about $1.4 million today). His heirs finally received a small settlement in 1911. What Would You Have Done? When the Union Army occupied Murfreesboro, they forced all business owners to sign an oath of loyalty to the United States if they wanted to continue operating their businesses. With so many of their friends and family members supporting the Confederate cause, this created a difficult choice between economic survival and the respect of their community. What would you have done? Emancipation Photos: Emancipation (Image: Emancipation 1863 Harper's; Image 17: Runaway Slaves Harper's) USCT (Image 11 Civil War and Negro Soldiers Harper's) Contraband Labor (Image 12: Contraband Harper's 1863) Slaves escaping to follow troop (maybe Murfree Plantation)—Smithsonian image James Garfield Main Panel Label: Emancipation was also an important and inescapable part of the war. Freedom from slavery came early for African-Americans in Murfreesboro. In farm raids, Union soldiers often took slaves as contraband. For many slaves, however, they did not need to wait for the Union to come to them – they went to the Union on their own. Amid all the chaos that the war brought, slaves saw the opportunity to finally make their way to freedom. Group Label: African Americans abandoned their plantations and fled to Union camps hoping for freedom and acceptance. Leaving brought a new freedom for African-Americans. At the same time, this new freedom for African-Americans brought tension and distress among white residents who had to learn a new way of life without the help of their slaves. Group Label: In the summer of 1863, the first Federal regiment of African-American soldiers was formed in Murfreesboro, and was known as the 2nd U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment. After a reorganization of the troops, the unit's name was changed to the 13th Regiment, United States Colored Troops (USCT). Major General Rosecrans assigned the USCT to work on the Nashville & Northwestern Railroad, a 78-mile long supply line that connected Nashville to the supply depot at Johnsonville. The 17th Regiment, USCT was organized in Middle Tennessee after the Battle of Chicamauga. Possible Quotes: “The Negroes are all in high spirits, think they are soon to be free. You would be surprised at the great change in this country for the last three years. Then if a negro was found away from home without a pass he was taken up and whipped or beat most cruelly with a paddle or a leather strap and stripped naked . . . anyone was punished who was seen conversing with a negro—but now a white man can not go in and out of Murfreesboro without a pass nor can they bring out any goods of any kind without buying a permit.” Jane C. Warren to Electa Ames, February 7, 1864 “Ma’s negroes are growing more and more unruly. They are not only indolent & perfectly trifling every way, but, are very insolent & disobedient.” Journal of Bettie Ridley Blackmore, late 1863 Sidebar: James Garfield James Garfield worked as the chief of staff for General Rosecrans. In a letter to his wife, dated April 12, 1863, Garfield expressed his concern for African Americans and their well-being. He stated, “The Negro question is becoming one of great difficulty. We cannot easily dispose of all the able-bodied male Negroes here, for we take all we can find for teamsters and for workmen on our fortifications. I am urging, and I believe with success, that when the works are finished these Negroes shall be drilled and organized for their defense. But the trouble arises with the swarms of Negro women and children that flock to our lines for protection and support.” Sidebar: Hammett Dell Hammett Dell was a slave before the war. In a WPA slave narrative, Hammett Dell recalled that while he lived with his master after the war, his father ran away during the war. Hammett Dell believed that his father may have joined the Union army. After the War (Image 7: After the war music; Image 8: After the war reconciliation) Photos: Image of Union/Confederate vets at Stones River* Image of KKK* Image—First Vote Image—Freedman’s Bureau Image—Reconciliation image Casualties—Union/Confederate RC deaths? Graph—Avg. household income 1860-1870* Images of veterans who became civic leaders after war Main Panel Label: At the end of the war, Rutherford County was a very different place from what it had been just a few years before. The physical devastation and deforestation of the landscape was profound. Slavery had ended, bringing freedom for nearly half the county’s residents, but legal and economic restrictions left many African-Americans with an unclear future. The Freedman's Bureau worked to help former slaves to find work and resolve complaint of abuse from white residents. However, few former slaves were able to get the rights that were legally theirs. Former slave Ann Matthews recalled, "I dunno of but one slave that got land or nothin' when freedom was declared." Although the Civil War reduced the county’s economic growth for years afterwards, the county eventually rebounded with a dynamic mix of agriculture, commerce and industry. The war left deep scars on the landscape of Rutherford County, and in the hearts of its residents, that continue to heal with each passing generation. GIS This maps show that the Civil War touched virtually every town, hamlet and household in Rutherford County. Battles and skirmishes occurred in every town; foraging raids impacted farms and plantations throughout the county; and fortifications, roundhouses and signal stations could be found in several locations. Although the physical remains of this era have all but disappeared, it is important to remember that every corner of the county was directly impacted by the Civil War. Sponsors and Contributors Fast Signs Rutherford County Mayor’s Office MTSU Public Service Committee MTSU Public History Program MTSU College of Liberal Arts Barry Lamb Shirley Jones Rutherford County Archives Rutherford County Historical Society Albert Gore Research Center Oaklands Association Sam Davis Home Stones River National Battlefield MTSU Center for Popular Music MTSU Center for Historic Preservation MTSU Special Collections at Walker Library Bill Jakes Bill Ledbetter John Lodl Bethany Hall Amy Davis Tennessee State Library and Archives Library of Congress Smithsonian Institute Dr. Robert Hunt Dr. Derek Frisby Dr Van West Denise Carlton Dr. Brenden Martin Kimberly Tucker Jaryn Abdallah Claire Ackerman Jared Bratton Ashley Brown Leslie Crouch Rachel Drayton Kelsey Fields Natalie Goodwin Rachel Morris Charles Nichols Kristen O’Hare Sade Turnipseed