Factors affecting total fertility rates in developing countries

advertisement

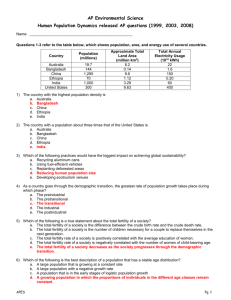

Statistique, Développement et Droits de l‘Homme Session C-Pa 5c Factors Affecting Total Fertility Rates in Developing Countries Abu Jafar SUFIAN Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistique, Développement et Droits de l‘Homme Factors Affecting Total Fertility Rates in Developing Countries Abu Jafar SUFIAN Professor, Department of Urban and regional Planning, King Faisal University PO Box 2397 Dammam 31451, Saudi Arabia T. + 966 3 8951748 (private) F. + 966-3 8578739 (office) drsufian@yahoo.com ABSTRACT Factors Affecting Total Fertility Rates in Developing Countries The effects of socioeconomic factors and family planning program effort on total fertility rate have been examined in this paper with national data for 50 developing countries. The explanatory variables chosen are: life expectancy at birth, infant mortality rate,per capita gross national product, energy consumption per capita, male literacy rate, percent of population with access to sanitation service, population density, per capita daily calories, female literacy rate, percent of urban population, percent of population with access to safe water supply, population per hospital bed, population per physician, number of oral dehydratation solution packets used per 100 diarrhea episodes, and family planning program effort score. The data came from the "Family Planning and Child Survival: 100 Developing Countries" compiled by the Center for Population and Family Health, Columbia University, and from the 1987 World Population Data Sheet. The multiple regression technique has been employed to identify variables that play important roles in determining the total fertility rate. The analysis shows that the family planning program effort has the largest contribution in lowering the total fertility rate, followed by percent of urban population, female literacy rate in that order. Policy implications are discussed RESUME Facteurs d’influence du taux total de fécondité dans les pays en voie de développement Ce document examine, à l’aide de données nationales de 50 pays en voie de développement, les effets des facteurs socio-économiques et des efforts effectués en matière de plannings familiaux sur le taux de fécondité. Les explications retenues sont les suivantes : l’espérance de vie à la naissance, le taux de mortalité infantile, le produit national brut par habitant, la consommation d’énergie par habitant, le taux d’alphabétisation chez les hommes, le pourcentage de la population ayant accès aux services sanitaires, la densité de la population, le nombre de calories par jour et par habitant, le taux d’alphabétisation chez les femmes, le pourcentage de la population vivant dans les villes, le pourcentage de la population ayant accès à l’eau potable, le nombre de lits d’hôpitaux pour la population, le nombre de médecins pour la population, le nombre de paquets de solution d’hydratation pour 100 cas de diarrhée et les efforts du programme de planning familial. Les données sont issues de l’ouvrage « Planning familial et survie chez l’enfant : 100 pays en voie 2 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistique, Développement et Droits de l‘Homme de développement », édité par le « Centre pour la santé de la population et des familles », Université de Columbia, et du rapport sur les données démographiques mondiales de 1987. La technique de régression a été employée pour identifier les variables qui jouent un rôle majeur dans la détermination du taux général de fécondité. Ces analyses montrent que les efforts du programme de planning familial ont très largement contribué à faire baisser le taux de fécondité, ainsi que la population vivant dans les villes et le taux d’alphabétisation chez les femmes. Les conséquences au niveau des mesures politiques sont également discutées. 1. Introduction It is evident that in recent years substantial fertility declines occurred in many of the developing countries – the average total fertility rate declined by half from 6.01 births per woman in 1965-70 to 3.00 births per woman in 1995-2000 (United Nations, 1999). A question of concern to demographers and other social scientists is whether this decline in fertility has been fostered mainly by the family planning programs. Indeed, this reduction in fertility has in some cases led to the belief that the gap between the fertility levels of the developing and developed countries can be substantially reduced by the socialization of family planning services. Available evidence, however, suggests that developing countries have considerable fertility as well as contraceptive use differentials among themselves (Population Reports, 1985). These differentials can well be attributed to the fact that socio-economic factors are often differentially distributed across social groups that exist in a society or between societies. Moreover, given that developing countries themselves differ considerably in terms of socio-economic development, it may be that the greatest reductions in fertility occurred in those countries that experienced significant socio-economic development. The effects of socio-economic factors on fertility have been examined in a number of studies. Education depresses fertility by increasing the age at marriage, and by increasing the likelihood of contraceptive use (Casterline, et al., 1984; Entwisle and Mason, 1985; Jiang, 1986; Kim, 1987; Krishnan, 1988; Prada and Ojeda, 1986; Rubin-Kurtzman, 1987). Total fertility rates are higher among rural women than among urban women (Alam and Casterline, 1984; Rubin-Kurtzman, 1987; Prada and Ojeda, 1986). Income has been found to be negatively related to fertility (RubinKurtzman, 1987; Jiang, 1986). Family planning programs exert very strong direct negative effects on fertility (Poston and Baochang, 1987; Cutright and Kelly, 1981; Mauldin and Berelson, 1978; Tsui and Bogue, 1978). The pivotal question in this paper is whether, and if so, to what extent, socio-economic and other developmental factors do induce changes in the national fertility levels, and how do these effects compare to that induced by the family planning program effort. It is believed that the socioeconomic and other developmental factors do exert significantly independent as well as joint influence on fertility after eliminating the effect of the family planning program effort. An attempt has been made in this paper to identify these factors and their relative contributions towards the variations in national fertility levels. The importance of the study derives from the fact that it is necessary to identify those population groups whose fertility is high but reducible through changes in government policy and a redistribution of available resources. 2. Methods and Findings The total fertility rate (defined as the number of live births a hypothetical woman would have if she survived tFactors Affecting Total Fertility Rates in Developing Countrieso the end of her reproductive period and experienced the given set of age-specific fertility rates) of 50 developing countries from Asia, Africa, aFactors Affecting Total Fertility Rates in Developing Countriesnd Latin America have been analyzed in this paper on the basis of data obtained from Family Planning 3 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistique, Développement et Droits de l‘Homme and Child Survival: 100 Developing Countries (Ross et. al., 1988) compiled by the Centre for Population and Family Health, Columbia University, New York, as well as from the 1987 World Population Data Sheet (Population Reference Bureau, 1987). The explanatory variables considered in this study are those that appeared influential in earlier studies in accounting for fertility variation. These variables are infant mortality rate, i.e., infant deaths per thousand live births, life expectancy at birth, population per square kilometer, per capita daily calories, male and female literacy rates i.e., percent of population 15 years old and over who can read and write, per capita gross national product, per capita energy use, percent of urban population, percent of population with access to safe water supply, population per hospital bed, population per physician, number of oral rehydration solution packets used per hundred diarrhea episodes, percent of population with access to sanitation services, and family planning program effort score based on four components: policy and stage setting, service, record keeping and evaluation, availability and accessibility. Ross et al., (1988) and Population Reference Bureau (1987) discussed these variables in more details. The final analysis was based on 50 observations for which values were available for all sixteen variables. Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations of the Dependent and the Explanatory Variables: 50 Developing Countries Variable Mean Total Fertility Rate 5.548 Life Expectancy at Birth 55.980 Infant Mortality Rate 92.366 Population per Square Kilometer 147.930 Per Capita Daily Calories 2302.980 Male Literacy Rate 68.040 Female Literacy Rate 51.440 Per Capita Gross National Product 796.304 Per Capita Energy Use 12.149 Percent of Urban Population 34.280 Percent of Population With Access to Safe Water Supply 46.240 Population per Hospital Bed 922.180 Population per Physician 11390.600 Number of Oral Rehydration Solution Packets Used per Hundred Diarrhea Episodes 31.900 Percent of Population With Access to Sanitary Services 41.833 Family Planning Program Effort Score 35.142 Standard deviation 1.460 8.639 37.665 376.970 392.486 20.480 26.815 895.908 21.989 17.838 23.723 1041.986 11718.343 32.782 27.791 25.473 The means and standard deviations for the dependent as well as for the explanatory variables are presented in Table 1. The total fertility rate has an average value of 5.6 children per woman varying from lows of 2.3 children in Maritius, and 2.4 children in Chile to highs of 8.5 children in Rwanda, and 8.0 children in Kenya. We hypothesize that life expectancy at birth, per capita gross national product, per capita energy use, percent of urban population, female and male literacy rates, percent of population with access to safe water supply, percent of population with access to sanitation services, per capita daily calories, number of oral rehydration solution packets used per hundred diarrhea episodes, and family planning program effort score will be nagatively related to total fertility rate while positive relationships are expected between total fertility rate and each of 4 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistique, Développement et Droits de l‘Homme infant mortality rate, population per square kilometer, population per hospital bed, and population per physician. Among the explanatory variables, female literacy rate and male literacy rate are highly correlated (0.93), and so are percent of population with access to safe water supply and percent of population with access to sanitation services (0.80) (correlation matrix not shown here). To avoid the problem of multicollinearity which is associated with unstable estimated regression coefficients, male literacy rate and percent of population with access to sanitation services have not been included in the regression model. The bivariate correlations do not take into account the relationship of an independent variable with all other independent variables (Lewis-Beck, 1980), and as such each independent variable (excluding those deleted before) has been regressed on all the other independent variables in order to assess whether there can be any further problem of multicollinearity. Four of the R 2 s from these equations corresponding to the regressions of infant mortality rate, life expectancy at birth, per capita energy use, and per capita gross national product are near 1.0 (0.93, 0.95, 0.94, 0.95 respectively), indicating that multicollinearity is still a problem. To get rid of this problem, these four variables have been dropped out from further analysis. The final analysis has, therefore, been based on the variables total fertility rate (response Y), percent of urban population (X1), percent of population with access to safe water supply (X2), population per square kilometer (X3), per capita daily calories (X4), female literacy rate (X5), family planning program effort score (X6), population per hospital bed (X7), population per physician (X8), and number of oral rehydration solution packets used per hundred diarrhea episodes (X9). The results of fitting the multiple regression model: (1) Y = 0 + 1X1 + 2X2 + 3X3 + 4X4 + 5X5 + 6X6 + 7X7 + 8X8 + 9X9 are presented in table 2. The value 0.72 of R2 can be considered as quite large. This does not, however, imply a good fit (Anscombe, 1973), nor that the model assumptions have not been violated (Chatterjee, and Price, 1977). Plots of the standardized residuals against the fitted values as well as against the explanatory variables did not show any systematic pattern of variation and all the standardized residuals fell between +2 and -2. Neither did they detect the presence of any outliers. Consequently, there is no evidence for model misspecification or for serious violations of model assumptions. The high value of R2 indicates that 72 percent of the variation in the total fertility rate is due to fluctuations in the nine explanatory variables. This reflects the adequacy of the explanatory variables as well as the accuracy of the equation. The F test of the model has also shown a very high significance of the equation. The explanatory variables - percent of urban population, female literacy rate, and the family planning program effort score - affect the total fertility rate significantly, and their effects are negative. The slope estimates show that a one percent increase in the urban population is associated with a decrease of 0.028 children per woman, a one percent increase in the female literacy rate is associated with a decrease of 0.016 children per woman, and a unit increase in the family planning program effort score decreases the number of children per woman by 0.036, in each case holding all other variables constant. Table 2. Unstandardized and Standardized Coefficients of Regression of Total Fertility Rate on the Nine Explanatory Variables. 5 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistique, Développement et Droits de l‘Homme Variable Unstandardized coefficients t-Value pr > T Standardized coefficients Intercept 8.75181651 7.54 0.0001 Percent of urban population (X1) -0.02806448 -2.75 0.0088 -0.3429972 Percent of population with access to safe water supply (X2) -0.00175078 -0.21 0.8312 -0.0284555 Population per square kilometer (X3) -0.00046436 -1.28 0.2085 -0.1199180 Per capita daily calories (X4) 0.00003280 0.07 0.9415 0.0088201 Female literacy rate (X5) -0.01557470 -2.48 0.0173 -0.2861435 Family planning program effort score (X6) -0.03606516 -5.82 0.0001 -0.6294263 Population per hospital bed (X7) 0.00027246 1.85 0.0716 0.1944681 Population per physician (X8) -0.0000334 -1.99 0.0535 -0.2681588 Number of oral rehydration solution packets used per hundred diarrhea episodes (X9) 0.00095609 0.24 0.8149 0.0214720 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------N=50 R2= 0.716068 0.72 S=0.86078647 0.86 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------In order to evaluate the relative importance of the explanatory variables in determining the total fertility rate, the standardized coefficients are examined (table 2). These coefficients show that a one standard deviation increase in the percent of urban population is associated with a 0.34 standard deviation decrease, on the average, in the total fertility rate, a one standard deviation increase in the female literacy rate is expected to induce, on an average, a 0.29 standard deviation decrease in the total fertility rate, while a one standard deviation increase in the family planning program effort score is associated with a 0.63 standard deviation decrease, on the average, in the total fertility rate, in each case, with all other explanatory variables held constant. We conclude that the impact of family planning program effort, as measured in standard deviation units, is the largest in lowering total fertility rate, followed by percent of urban population, and female literacy rate. 3. Summary and Conclusions The cross-national variation in total fertility rate has been analyzed in this paper using multiple regression technique with national data for 50 developing countries. The analysis shows that percent of urban population, female literacy rate, and family planning program effort score are significantly related to total fertility rate. The standardized coefficients have been examined to assess the relative importance of the explanatory variables in determining the total fertility rate. The family planning program effort has the highest impact on the total fertility rate followed by percent of urban population, and female literacy rate. Indeed, the effect of the family planning program effort is almost two times greater than that of the percent of urban population, and more than two times greater than that of the female literacy rate. This study has a number of policy implications. The family planning program effort is the most important contributor to the reduction of total fertility rate. This lends support to the contention that the determinative factor that has fostered the recent decline in fertility in the developing countries has been mainly the government's family planning programs. The other variable significantly related to the total fertility rate is the percent of urban population. The higher this percentage the lower the total fertility rate. Urban areas are usually the 6 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistique, Développement et Droits de l‘Homme centres of political and economic power and a great part of resources and social services are concentrated in them. As such, people living in urban areas enjoy relatively more opportunities of modern life which is conducive to having smaller family size. In developing countries larger segments of population live in rural areas. Benefits of socio-economic development are distributed unequally among the social groups: rural population who need more care, receive less care indeed. The third variable significantly related to the total fertility rate is the female literacy rate. The higher the literacy rate, the lower the total fertility rate. Better educated women enjoy better access to opportunities of life, and hence lower fertility is felt more advantageous to them than higher fertility since with lower fertility it is easier to reap the benefits of those opportunities. Among women with no education, even significant difference in the number of children fails to make any observable difference in the level of living, and as a result lower fertility does not appear to them as a favourable life condition. As such, societies with lower levels of literacy have greater likelihoods of having larger fertility rates. Thus, although the family planning programs have played the most important role in developing countries in the recent declines of fertility levels, these declines should not be viewed as due solely to successful family planning programs. The results of this analysis indicate that an egalitarian distribution of the benefits of socio-economic development over the rural and urban areas might produce better results in terms of fertility reduction in developing countries. Also, raising the level of female literacy may be one of the important strategies for reducing the fertility rate. These results also parallel those of Freedman et al., (1988) who observed that in China the "family planning program has been able to transcend the barriers of illiteracy and low educational levels, but that education was nevertheless related to reproductive levels, both before and after the major program effects". REFERENCES Alam, I., and J.B. Casterline. (1984). Socio-economic Differentials in Recent Fertility. Voorburg, Netherlands. International Statistical Institute. World Fertility Survey Comparative Studies: CrossNational Summaries No.33. Anscombe, F.J. (1973). Graphs in Statistical Analysis. American Statistician 27:17-21. Casterline, J.B., S. Singh, J. Cleland, and H. Ashurst. (1984). The Proximate Determinants of Fertility. Voorburg, Netherlands. International Statistical Institute. World Fertility Survey Comparative Studies No.39. Chatterjee, S., and B. Price. (1977). Regression Analysis by Examples. John Wiley and Sons. Cutright, P., and W.R. Kelly. (1981). The Role of Family Planning Programs in Fertility Declines in Less Developed Countries, 1958-1977. International Family Planning Perspectives 7:145-151. Entwisle, B. and W.M. Mason. (1985). What Has Been Learned from the World Fertility Survey About the Effects of Socio-economic Position on Reproductive Behaviour. Population Studies Center Research Report No.85-77. University of Michigan, Population Studies Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Freedman, R., Zhenyu Xiao, Bohua Li., and William R. Lavely. (1988). Education and Fertility in Two Chinese Provinces: 1967-1970 to 1979-1982. Asia-Pacific Population Journal Vol 3 (1):3-30 Bangkok. 7 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistique, Développement et Droits de l‘Homme Jiang, Zhenghua. (1986). Impact of Socio-economic Factors on China's Fertility. Population Research Vol.3(4):9-17. Kim IK Ki. (1987). Socio-economic Development and Fertility in Korea. XV. Seoul National University, Population and Development Studies Center. Seoul, Korea. Krishnan, Vijaya. (1988). Homeownership: Its Impact on Fertility. Population Research Laboratory Discussion Paper No.51. University of Alberta, Department of Sociology, Edmontan, Canada. Lewis-Beck, Michael S. (1980). Applied Regression: An Introduction. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, California. Mauldin, W.P., and B. Berelson. (1978). Conditions of Fertility Decline in Developing Countries. Studies in Family Planning 9: 89-147. Population Reference Bureau, Inc. (1987). 1987 World Population Data Sheet, Washington D.C. Population Reports. Series M. Number 8 (Special Topics): 290. (1985). The Johns Hopkins University, Maryland. Poston, Dudley L., and Baochang Gu. (!987) Socio-economic Development, Family Planning, and Fertility in China. Demography 24 (4): 531-551. Prada, E., and Gabriel Ojeda. (1987). Selected Findings from the Demographic and Health Survey in Colombia, 1986. International Family Planning Perspectives Vol. 13 (4): 116-20. Ross, John A., Marjorie Rich, Janet P. Molzan, and Michael Pensak. (1988). Family Planning and Child Survival:100 Developing Countries. Center for Population and Family Health, Columbia University, New York. Rubin-Kurtzman, Jane R. (1987). The Socio-economic Determinants of Fertility in Mexico: Changing Perspectives. Center for U.S. - Mexican Studies Monograph Series No.23. University of California, La Jolla, California. Tsui, A.O., and D.J. Bogue. (1978). Declining World Fertility: Trends, Causes, Implications. Population Bulletin 33(4): 1-42. United Nations. 1999. World Population Prospects: The 1998 Revision. New York. 8 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistique, Développement et Droits de l‘Homme 9 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000