Puns Lost, Puns Regain`d: The pun in Paradise Lost and Paradise

advertisement

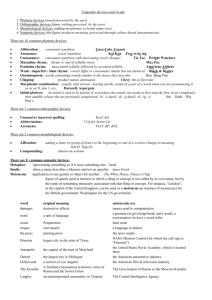

Puns Lost, Puns Regain’d: The pun in Paradise Lost and Paradise Regain’d. Good afternoon, today I want to take a short stroll through my thesis. The ideas presented here form the core of my thesis after three years of musing, ruminating, and gesticulating at books with my pipe. I have been examining uses of the pun in canonical literature from Shakespeare to Pope. Renaissance writers were not shy of a pun or two. However, using the term ‘pun’ to refer to what they were doing is anachronistic. The meaning of the word ‘pun’ that we are familiar with was first used by Dryden in 1662. What we term an act of punning would, in actual fact, be one of five rhetorical techniques that all writers of this period would have been familiar with due to the humanist educators of the time deciding that the classical art of rhetoric was a vital part of education along with grammar, Latin, and the cane. The five techniques are Paranomasia, Antanaclasis, Asteismus, Syllepsis, and Polyptoton. Paranomasia, simply put, is a homophonic pun. Syllepsis is a homonymic pun. Asteismus requires two speakers and the second speaker to misinterpret one of the first speakers words. Hamlet uses this technique to convince people that he is a pinch of tobacco short of a full pipe. Polyptoton I wish to discuss in some depth later on. Antanclasis is where one word is used two or more times in relatively close succession and where the meaning of the word shifts with each use. Here, for example, is perhaps the most extreme case of antanaclasis that I know of. 135 Who ever hath her wish, thou hast thy Will, And Will too boote, and Will in over-plus, More then enough am I that vexe thee still, To thy sweet will making addition thus. Wilt thou whose will is large and spatious, Not once vouchsafe to hide my will in thine, Shall will in others seeme right gracious, And in my will no faire acceptance shine: 1 The sea all water, yet receives raine still, And in aboundance addeth to his store, So thou being rich in Will adde to thy Will, One will of mine to make thy large Will more. Let no unkinde, no faire beseechers kill, Thinke all but one, and me in that one Will. Joel Fineman noted that for some people, this sonnet shows Shakespeare at his worst and went on to argue that by repeating his name in this sonnet Shakespeare disrupts the unity of an ‘I’ voice by explicitly demonstrating the distance between the ideal representation of subjectivity, the ‘I’ of the poet and the ‘you’ that is the ideal representation of the object, the Dark Lady , and the inability of ‘Will’ to fully express the being that is ‘William Shakespeare,’ the Dark Lady’s desire and a number of other signifieds inbetween. By indulging in an extreme case of antanaclasis, thirteen repetitions of the word ‘will’ – fourteen if you include ‘wilt’, Shakespeare tests the limits of the word ‘will’ to signify meaning. When reading the poem, the word ‘will’ becomes stripped of meaning by the excessive use, so many meanings are used that the word becomes overburdened we begin to simply hear it as a sound and fury signifying nothing. Will, will, will, will, will, will, will, will. The final line exemplifies all the tensions of the poem. The poet expresses a desire for the Dark Lady to unify everything into one ‘will’ that is constructed of all the other wills including the poet. His desire for her desire to be ‘one’ – to have a stable identity is destroyed by the inability of the word ‘will’ to refer to any one, single, meaning anymore. Exemplified here is the logic of the pun driving the logic of the poem. The poets and critics of the eighteenth century were well aware of this problem inherent in language. Several times people called for language to be cleaned up and become more mathmatical in nature, most famously, perhaps, by Sprat in his History of the Royal Society who piped up with a call for a “mathematical plainness” in language. As we are all well aware, theory and practice rarely meet. However, the puns of Pope differ dramatically from those of Shakespeare. Here is one of Pope’s most famous puns: Where Bentley late tempestuous wont to sport 2 In troubled waters, but now sleeps in Port. - The Dunciad IV.201-202. This syllepsis is clean, comprehendable, and easily contains its two meanings without ever being in any danger of the ‘non-meaning’ that threaten’s Shakespeare’s ‘Will.’ The closest Pope ever comes to the potential confusion that punning always flirts with is in The Rape of the Lock: Where wigs with wigs, with sword-knots sword-knots strive, Beaux banish beaux, and coaches coaches drive. The Rape of the Lock I.101-2. The OED defines ‘sword-knot’ as: a ribbon or tassel tied to the hilt of a sword. The repetition of ‘sword-knots’ here could be read as not being a pun at all, that people are competing simply through extravagant ornamentation but it also summons up a wonderful image of a knot of swords in actual combat. This comes about through antanaclasis as the repetition of the word forces your ear to hear it again, giving you mind second go at defining the word – opening it up. The play is limited though and it is carefully controlled by Pope. The effect is happening not just with sword-knot sword knot but also wigs with wigs, beaux banish beaux and coaches coaches drive. The overall effect is of a calculated semantic confusion to mimic the confusion of wigs, sword-knots, beauxs and coaches. By not giving us time to dwell overly long on one particular repeated word, Pope refuses to follow the logic of the pun to its conclusion as Shakespeare did in Sonnet 135. These examples go some way towards demonstrating the difference in use of pun techniques between the eighteenth century and the Renaissance. What happened to cause such a change in use? The short answer is that along with all the political, theological and economic changes between the two periods, in poetical terms, Milton happened. [“But what have been thy answers, what but dark Ambiguous and with double sense deluding,” (Milton – Paradise Regain’d I.434-5.) 3 ‘One word with two meanings is the traitor’s shield and shaft: and a slit tongue be his blazon!’ – Caucasian Proverb. (Coleridge – ‘Alice Du Clos or The Forked Tongue: A Ballad.’)] However, let me now attempt a longer answer. The common view of critics, as expressed by Christ in Paradise Regain’d, is that ambiguity is a hallmark of the Satanic style. Shoaf, in Milton, Poet of Duality defines ambiguity as “duplicity, the vice of language, two intentions contend for the same semantic space, decietful and designing, choice and liberty revoked.” It was Walter Landor who made the famous claim that the fallen angels fell because they punned. The most infamous example of punning in Paradise Lost occurs during the War in Heaven in book 6. Vanguard, to Right and Left the Front unfould; That all may see who hate us, how we seek Peace and composure, and with open brest Stand readie to receive them, if they like Our overture, and turn not back perverse; But that I doubt, however witness Heav’n, Heav’n witness thou anon, while we discharge Freely our part; yee who appointed stand Do as you have in charge, and briefly touch What we propound, and loud that all may hear. So scoffing in Ambiguous words, (Raphael relating Satan’s speech – Paradise Lost VI.558-568.) Bentley, when not sleeping in port, found time to comment on this section: “These passages, of Satan and Belial’s insulting and jesting Mockery, have been often censur’d; especially be an ingenious Gentleman, who had a settled Aversion to all Puns, as they are called; which niceness, if carried to Extremity, will deprciate half of the Good Sayings of the old Greek and Latin Wits. I’ll not engage in the Opinions of either Side. But, for my Author’s Vindication, I’ll observe, that he copied from his great Predecessor Homer; who makes Patroclus, after he had slain Cebriones, 4 Hector’s Charioteer, to take the like jocose insulting Humor.” Bentley here telling Addison to stick that in his pipe and smoke it. Neil Forsyth in The Satanic Epic argued that “what makes these puns so tiresome is the schoolboy knowingness that one hears in the speaking voice, one imagines the other devils tittering as the clever Satan delivers his taunting double-entendres.” And this section ably demonstrates Robert Entzminger’s claim that “demonic puns are intended both to mock and to decieve, and Satan’s rhetoric is adopted for its calculated effect on his hearers.” The word that Forsyth claims is most played upon throughout the Paradise Lost is ‘dis-’. We find a ‘dis-’ word in the first line of the epic – “disobedience” and we find it here in the extract from Satan. Like Shakespeare, Milton was a great inventor of words. Being his longest sustained work, Paradise Lost is where most of Milton’s inventing went on and Milton’s favoured form of invention, as has been noted by scholars, was to attach a negative prefix to a word that until then had not borne a negative prefix. Forsyth claims that “‘de-’ or ‘dis-’ are the results of the Fall, and that the range of these prefixes define Paradise Lost’s Satanic movement from unity to separation and discord. ‘Discharge’ as used by Satan here, I think, proves Forsyth’s point. Discharge, as we know, is a word used to describe firing a firearm and here is applied to the firing of Satan’s recent invention, cannons. However, it also means and here I quote the OED: “4. a. The act of freeing from obligation, liability, or restraint; release, exoneration, exemption.” Think of a soldier being honourably discharged. While they “discharge / freely our part” they are engaging in an act that they believe will free them of obligation to God, release them from what they perceive as enslavement to God and Christ. Dis was Virgil’s name for the King of the Underworld and in Paradise Lost milton uses this to give ‘dis-’ the prefix the added echo of death. So we also get the ironic ‘death’ joined with ‘charge’ which in its earliest meaning meant ‘ material load, that which can be borne, taken or received.’ Quite literally the Devils who think that they are freeing themselves by shooting canons are in actual fact burdoning themselves with death. That burdon they will share with us after Adam 5 and Eve’s fall but for the fallen angels it is a burdon that offers no salvation or escape – they fall and death is created but death teases them with an oblivion which they can never experience. Being a pun loving public, we should not fail to hear the “death load” in discharge applying in a rather grisly, though ultimately ironic, manner to the cannon balls themselves – a load of death for we mortals and not really too much trouble if you are an immortal angel. In Paradise Lost, Milton baroquely, and negatively, connects punning with Satan. However, in speeches by God and Christ, in the style of books 11 and 12 of Paradise Lost, Milton displays a new poetic, a poetic that is further exemplified and explored in Paradise Regain’d and after that Samson Agonistes; anticipating the Eighteenth Century poetic further down the pipeline. It is important to note that while punning has been connected to Satan and satanic rhetoric, puns still exist in this alternative poetic but they are not highlighted as they are with Satan. For example: But God who oft descends to visit men Unseen, and through thir habitations walks To mark thir doings, them beholding soon, Comes down to see thir Citie, ere the Tower Obstruct Heav’n Towrs, and in derision sets Upon thir Tongues a various Spirit to rase Quite out thir Native Language, and instead To sow a jangling noise of words unknown: Forthwith a hideous gabble rises loud Among the Builders; each to other calls Not understood, till hoarse, and all in rage, As mockt they storm; great laughter was in Heav’n And looking down, to see the hubbub strange And hear the din; thus was the building left Ridiculous, and the work Confusion nam’d. (Michael – Paradise Lost XII.48-62) 6 This extract, from book 12 of Paradise Lost demonstrates how different this poetic is from the Satanic poetic that has dominated so much of Paradise Lost. What is noticable here is what is deliberately absent. This section is about the Tower of Babel and the Milton who wrote the Eve / evil pun, the Milton who wrote the tempted / attempt pun, the Milton who wrote the sin / sign pun, the very same Milton will not allow Michael to make a Tower of Babel and babble pun. The OED claims that no direct connexion of babble “with Babel can be traced; though association with that may have affected the senses.” But incorrect etymologies never stopped Milton – remember the raven / ravenous pun in Paradise Regain’d. At the conclusion, where one expects the name “babel” we are given “confusion” instead. While I admit to a predisposition towards granting the possibility of a pun I find here only the deliberate absence of a pun. I am not arguing that this holds true for all of books eleven or twelve, Paradise Regain’d and Samson Agonistes. What I am arguing is that in these texts there is a deliberate effort to admit to polysemy and to control it – and as evidenced in this passage, through absence if necessary. The poetic equivalent of saying “no pun intended” whereby the pun is acknowledged and ignored, a highlighted self-censorship. It is polyptoton that becomes the central pun technique of Milton’s new poetic because it is the favoured technique of Christ. Polyptoton, is where a word is repeated but in a different case or inflection. As evidenced here, in book 3 of Paradise Lost where we first meet Christ: O Father, gracious was that word which clos’d Thy sovran sentence, that Man should find grace; For which both Heav’n and Earth shall high extoll Thy praises, with th’innumerable sound Of Hymns and sacred Songs, wherewith thy Throne Encompass’d shall resound thee ever blest. For should Man finally be lost, should Man Thy creature late so lov’d, thy youngest Son Fall circumvented thus by fraud, though joynd With his own folly? that be from thee farr, That farr be from thee, Father, who art Judg 7 Of all things made, and judgest onely right. Walter Nash asserts that polyptoton when “deliberate it is often a form of word-play. Strictly speaking, this figure is proper to richly inflected languages with their variety of word-endings denoting case, tense, mood and so on. The English examples might be described as pseudopolyptoton.” What I would claim is that polyptoton is a rhetorical technique that works in English but that it only carries the disruption of being a pun in some instances. The changing of ‘gracious’ to ‘grace’ and ‘judge’ to ‘judgest’ do not stike me as being puns but are instances of polyptoton. ‘Sound’ to ‘resound’, is a pun and a polyptoton. What polyptoton allows the poet to do is to utilize the polysemous potential of language by explicitly calling attention to the changing of the word and meaning. Instead of making one word, or one sound, or the repetition of one word carry multiple denotations, polyptoton allows multiple meanings to build up through multiple words. It shows how language is linked, how one sound is linked to another similar sound and how meanings are built up and differentiated. It is at once a nod to the metamorphic nature of language and a controlled use of that metamorphosis. No more shalt thou by oracling abuse The Gentiles; henceforth Oracles are ceast, And thou no more with Pomp and Sacrifice Shalt be enquir’d at Delphos or elsewhere, At least in vain, for they shall find thee mute. God hath now sent his living Oracle Into the World, to teach his final will, And sends his Spirit of Truth henceforth to dwell In pious Hearts, an inward Oracle To all truth requisite for men to know. So spake our Saviour; As Christ makes clear, in this speech, Satan is being quietened. No more shall Satan provide oracles. I think that the way Christ really rams this point home to Satan is by using the polyptoton. The ‘oracling; and ‘oracles’ of Satan are here reduced through polyptoton to one oracle, Christ. There is a subtle shift in the antanaclasis at the end 8 in the repetition of ‘oracle’. It moves from being Christ to Christ’s word that will become the Bible in centuries to come. But, it is still the same Oracle because Christ is the Word, ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God.’ as the Gospel of John reminds us. Christ shows the incorrect uses of the word oracle and then he shows us the correct use of the word. I believe that it is here, in Paradise Regain’d that Milton attempts to redeem language through Christ and what we end up with is an Eighteenth Century poetics. We have moved from a freer, Satanic, play to a more restrained, more focussed, Christ like play, where the ideal is not necessarily for one word one meaning –that is a pipe dream, as Milton knew and Paradise Lost is a testament to that. Much of the power and sublimity of Paradise Lost comes from Milton’s struggle to represent God, Christ, and Paradise through an imperfect, fallen, language. Milton, as I hope I have demonstrated in some small way in this paper, attempted to compensate for the Satanic elements in our fallen language through the use of polyptoton. For better or for worse, the poets of the eighteenth century picked up on this poetic and produced, in poetry that attempted to subdue the logic of the pun. 9