Habermas` comprehensive Theory of Society

advertisement

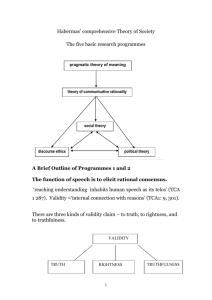

Habermas’ Comprehensive Theory of Society The five basic research programmes pragmatic theory of meaning theory of communicative rationality social theory discourse ethics political theory A Brief Outline of Programmes 1 and 2 1. Communication/Communicative Action The function of speech is to elicit rational consensus. ‘reaching understanding inhabits human speech as its telos’ (TCA 1 287). Verständigung = agreement, understanding, consensus Validity =‘internal connection with reasons’ (TCA1: 9, 301). There are three kinds of validity claim – to truth, to rightness, and to truthfulness. 1 VALIDITY TRUTH RIGHTNESS TRUTHFULNESS Communicative Action = action coordinated through validity-claims and thus oriented towards consensus Instrumental/Strategic Action = action oriented through success, and thus not oriented towards consensus. Success is achieved via a causal intervention the world 2. Discourse: Discourse arises with a challenge issued by the hearer to the speaker to make good her validity claim. There are three types of validity claim (truth, rightness and truthfulness) and three corresponding types of discourse, theoretical, moral and aesthetic. DISCOURSE THEORETICAL MORALPRACTICAL AESTHETIC Discourse is basically a social game through which social rules (norms) are justified, once they have lost their apparent self-evidence. The social function of discourse is to make possible interaction by to repair the consensus that constitutes the social fabric. 2 Picture of Modern Society Lifeworld and System Lifeworld home of communication and discourse & System sphere of “norm-free sociality”. Danger of Colonisation of the lifeworld by the system. (E.g. destructive effect of markets on hitherto unmarektised domaisn of social life.) Communicative rationality versus Instrumental and strategic rationality. Instrumental and strategic actions are aimed at success, and at achieving success, . Summary of The Theory of Communicative Rationality Basic questions: What are the fundamental types of action? What is the difference between them? Which type is prior or more fundamental? In virtue of what? 3 Basic answers: There are two types of action: communicative action on the one hand, instrumental and strategic action on the other. The difference is that communicative actions aim at securing understanding and consensus, while instrumental and strategic actions aim at practical success. Communicative action is the more fundamental because it is self-standing; instrumental and strategic action are not. 3. The programme of social theory Habermas’s Social Ontology Communicative Action Instrumental/Strategic Action Lifeworld e.g. family, public sphere System Money (economy) Power (state) Basic questions: What are modern societies like? Of what are they made? Basic answers: Modern societies are made up out of two kinds of social being – the lifeworld and the system. The lifeworld is the home of communication and discourse. The system is the home of instrumental and strategic actions. Critical Social Theory Basic questions: What is the underlying cause of the pathologies of modern social life? Basic answers: Systems – markets and administrations – expand and colonize the lifeworld, the home of communicative action and discourse on which they themselves depend. People are forced into patterns of ecomically or administratively induced instrumental and strategic action, in spheres of what Habermas calls ‘norm free sociality’. Conclusion: The lifeworld needs to be kept intact, and the ill-effects of systems intrusion into non-system domains, the marketisation of spheres of sociality that were formerly not market driven, must be mitigated. 4 4. The programme of discourse ethics A) The discourse theory of morality 1.) The Rules of Discourse Moral discourse not a free for all but a disciplined, rule-governed practice. Discipline is given by internal pragmatic preconditions, rules of the game of argumentation. These norms insulate discourse from all persuasive forces except the ‘unforced force of the better argument’, and they must be followed, if a rationally motivated consensus is to be reached. Habermas argues that the following basic norms or rules of discourse can, as it were, be distilled from the idealizing pragmatic preconditions that must always already be made by participants in discourse. (a) Every subject with the competence to speak and act is allowed to take part in the discourse. (b) i Everyone is allowed to question any assertion whatsoever. ii Everyone is allowed to introduce any assertion whatsoever into the discourse. iii Everyone is allowed to express his attitudes, desires and needs. (c) No speaker may be prevented, by internal or external coercion, from exercising his rights as laid down in (a) and (b) above.1 Habermas has a theory about the social function of morality. To re-establish the rational consensus that forms the normative fabric of society. The discourse principle (D), states that: (MCCA 89: ED 161) I have cited this from W. Rehg’s Insight and Solidarity, (Berkeley: University of California Press) rather than from MCCA 89 where Habermas quotes R. Alexy Theorie der juristischen Argumentation (Frankfurt: Surkamp, 1983), 169, translated in (CEC 166). 1 5 Only those action norms are valid to which all possibly affected persons could agree as participants in rational discourse. (BFN 107) Habermas claims that once you have the rules of discourse, above, and principle (D), the moral principle (U) (for Universalization). Why doesn’t he provide a derivation? Rehg/Me (U) a norm is valid if and only if the foreseeable consequences and side effects of its general observance for the interests and value-orientations of each individual could be freely and jointly accepted by all affected. (TIO 42) Basic questions: How is moral order possible? What makes an action morally right or wrong? How do we know, and how do we learn, what is right/wrong? Basic answers: Moral order rests on the existence of demonstrably valid norms and the fact that most agents are disposed to adhere to them. What makes an action right/wrong is that it is permitted/prohibited by a valid moral norm. What makes a norm valid is that it demonstrably embodies a universal interest. We find out whether this is the case by testing candidate norms for their capacity to elicit rational agreement in moral discourse. ii) ethics Basic questions: What is distinctive about ethical as opposed to moral questions? What is the social and political significance of ethical questions? Basic answers: Ethical discourse concerns questions of individual happiness and the good of communities. Ethical discourse involves critical appropriation of traditions and the interpretation of values. Ethical Discourse make claims to authenticity. (Looks like a practical correlate of sincerity or truthfulness.) 5. The programme of political theory 1) Habermas’s Conception of Politics: The ‘Two-Track’ Structure of Politics. Strong Publics Formal sphere = institutional arenas of communication and discourse designed to take decisions, E.g. parliaments, cabinets, elected assemblies and political parties. N.B. not identicial with the state. 6 Weak Publics The informal political sphere = not institutionalised and not designed to take decisions e.g. ‘civil society’, voluntary organisations, political associations and the media etc.. ii. Human Rights and Popular Sovereignty H’s conception of political community combines central ideas of liberal-democracy and civic republicanism. Western democracies have arisen from two different traditions that are intension with each other. Rather than an uneasy compromise (Geuss) he sees democracy as a way of harnessing the productive tension for socially useful ends Liberal democracy and the idea of human rights, Civic republicanism on the idea of popular sovereignty. a. Human Rights Govt. must respect the rights of and the private autonomy of the individual. b. Popular Sovereignty Popular sovereignty is the idea that the political authority of the state resides ultimately in the will of the people. c. The Equiprimordiality and Reciprocity of the Two Ideas Habemras argues that human rights and popular sovereignty are equiprimordial and reciprocal, i.e., that neither comes first, and that each mutually depends on the other. Politics is the expression of ‘the freedom that springs simultaneously from the subjectivity of the individual and the sovereignty of the people.’ (BFN 468) Habermas denies three key liberal assumptions: that rights belong to pre-political individuals; that membership in the political community is valuable merely as a means to safeguard individual freedom; that the state should remain neutral in respect of the justification of its policies or laws, where neutrality implies avoiding appeal to values and ethical considerations. Habermas rejects three key civic republican assumptions: that the state should embody the values of the political community. 7 That state and society can be understood on the model of a large assembly or parliament. that participation in the community is the realisation of these values; that subjective rights derive from and depend on the ethical self-understanding of the community “Popular sovereignty is not embodied in a collective subject, or a body politic on the model of an assembly of all citizens, it resides in ‘“subjectless” forms of communication and discourse circulating through forums and legislative bodies.’ (BFN 136) However, in its republican form this idea assumes that society can be construed as a single culturally homogeneous people who gather together in an assembly.i Given the size, and the internal differentiation and complexity, not to mention the cultural pluralism of modern society, this idea has to be modified. Nowadays, democratic decision-making bodies (Habermas also calls these ‘strong publics’) form “the core structure in a separate, constitutionally organised political system.” The republic is not a model for society at large nor even “for all government institutions” and society cannot be conceived as a parliament or assembly write large, because ”the democratic procedure must be embedded in a context it cannot itself regulate.” (Habermas, 1996: 305) Formal political institutions must be open to open to the “input from below” so that their decisions, policies and laws will be tend to be rational and to find acceptance. This is where the system of rights comes in. Habermas argues that ‘the system of rights states the conditions under which the forms of communication necessary for the genesis of legitimate law can be legally institutionalised.’ (BFN 103) 2) Politics and the Form of Law Between Facts and Norms, literally translated would be Facticity and Validity. i. The Dual Structure of Law A law is legitimate when it has a point, or when there are appreciable reasons for obeying it. 8 A law is positive when it is laid down or imposed by some lawmaker (and coercible when it can be). Laws have a third feature too: they must be coercible. A legal norm is valid only when all these components are present. ii. The Legitimacy of Law Habermas formulates his notion of legitimacy in the principle of democracy. The democratic principle states that: Only those laws count as legitimate to which all members of the legal community can assent in a discursive process of legislation that has in turn been legally constituted. (BFN 110) The democratic principle arises from the ‘interpenetration’ of principle (D) and the legal form. According to (D), amenability to consensus is a mark of the validity of a norm. The mark of a norm’s legitimacy is this: Legitimate laws have to be able to win the assent of all members of the legal community, not as outcome of a rational discourse of all concerned, but of a legally constituted process of legislation. We can summarise Habermas’s very complex theory with the following schema. If a political norm is valid, then: (I) a. Its violation is punishable by some legitimate sanction b. There exists generally effective and legitimate mechanism for applying it – (punishable here implies the existence of the police and the judiciary as organs of the state). c. The members of the legal community generally know that a. and b. obtain. d. This is sufficient to ensure average compliance. In addition to the conditions set out in (I), if a political norm is valid, then: (II) a. It has some intrinsic rationale or point independent of (I). b. Its rationale connects with the common good of the legal community and its members. c. Its rationale is open to view and generally understood. d. In virtue of a, b, and c the law is such that members of the legal community have good reason to obey it. 9 This schema helps is to distinguish between the validity (I + II), the legitimacy (II) and what Habermas calls the facticity or positivity of a political norm (I). Habermas claims that both the facticity (I) and legitimacy (II) are jointly sufficient conditions of the validity of a political norm, and that each is individually necessary. This means that the validity of a political norm (or law) is a much richer and more complex notion than that of the validity of practical norms in general, which notion of validity is that contained in (D) and is equivalent with acceptability in an ideally prosecuted discourse. Note also that (II) is independent of (I), insofar as (II) contains no reference to (I), but the reverse is not the case since (I) explicitly refers to (II), which signals the primacy of legitimacy over facticity. The primacy of legitimacy is not just a conceptual point, it tallies with the sociological fact that in modern, post-conventional, democratic societies, social order and the burden of social integration rest primarily (but not only) on the legitimacy of its laws and institutions.ii i) The discourse theory of politics Basic questions: How is a well-ordered political system possible? What makes laws, policies, and political decisions legitimate? Basic answers: A well-ordered political system is one in which the right balance between private and public autonomy is achieved and in which political order is stabilized to a large degree by rational decisions produced by institutions that are sensitive to the informal public spheres of civil society. Laws are legitimate only if they are in tune with the opinions, values, and norms generated discursively in civil society. ii) The discourse theory of law Basic questions: What is a valid law? What is the role of valid legal norms? Basic answers: A valid law is a law that is positive, enforceable, and legitimate. Legitimate laws must be consistent with moral, ethical, and pragmatic considerations and serve the good of the legal community. Valid legal norms authorize and implement political power. They support moral norms, help to harmonize individual action and to establish social order. For example: “Dans une cité bien conduite, chacun vole aux assemblées.” (Rousseau, 1964 : 428) i 10 Incidentally Rawls holds a similar view. In a liberal society governments are concerned not just with securing stability, but a particular kind of stability, “secured by sufficient motivation of the appropriate kind acquired under just institutions”. (Rawls, 2005: 143) ii 11