Summary and Analysis of Act I

advertisement

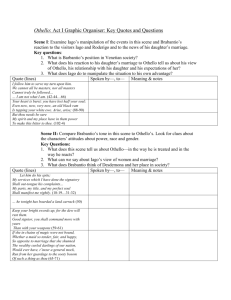

Summary and Analysis of Act I Act I, scene i: Summary Othello begins in the city of Venice, at night; Roderigo is having a discussion with Iago, who is bitter at being passed up as Othello's lieutenant. Though Iago had greater practice in battle and in military matters, Cassio, a man of strategy but of little experience, was named lieutenant by Othello. Iago says that he only serves Othello to further himself, and makes shows of his allegiance only for his own gain; he is playing false, and admits that his nature is not at all what it seems. Iago is aware that the daughter of Brabantio, a Venetian nobleman of some stature, has run off with Othello, the black warrior of the Moors. Desdemona is Brabantio's daughter, and Brabantio, and many others, know nothing of this coupling; Iago decides to enlist Roderigo, who lusts after Desdemona, and awaken Brabantio with screams that his daughter is gone. At first, Brabantio dismisses these cries in the dark; but when he realizes his daughter is not there, he gives the news some credence. Roderigo is the one speaking most to Brabantio, but Iago is there too, hidden, yelling unsavory things about Othello and his intentions toward Desdemona. Brabantio panics, and calls for people to try and find his daughter; Iago leaves, not wanting anyone to find out that he betrayed his own leader, and Brabantio begins to search for his daughter. Act I, scene i: Analysis The relationship between Roderigo and Iago is obviously somewhat close, as Roderigo shows in his first statement. Iago "hast had [Roderigo's] purse as if the strings were thine," he tells Iago; the metaphor shows how much trust Roderigo has in Iago, and also how he uses Iago as a confidante (I.i.2-3). Does Iago share the same kind of feeling? As far as Roderigo knows, Iago is his friend; but appearance is one thing and reality another, as Iago soon will tell. Iago tells several truths about himself to Roderigo; he even trusts Roderigo with the knowledge that Iago serves Othello, but only to further himself. How ironic that after Iago's lengthy confession of duplicity, Roderigo still does not suspect him of doublecrossing or manipulation. Iago seems to do a great deal of character analysis and exposition for the audience; here, he divulges his purpose in serving Othello, and the kind of man he is. Appearance vs. reality is a crucial theme in Iago's story; throughout the play, he enacts a series of roles, from advisor to confidante, and appears to be helping people though he is only acting out of his twisted self-interest. "These fellows" that flatter for their own purposes "have some soul," Iago says; there is a double irony in this statement that Iago passes off as a truth (54). People who act one way and are another are duplicitous, and scarcely deserve the credit that Iago is trying to give them. Also, Iago, though he is one of those fellows, seems to have no soul; he never repents, never lets up with his schemes, and never seems to tire of the damaging whatever he is able to. "In following [Othello] I follow but myself," Iago also professes; this is a paradox in terms, but is revealing of Iago's purposes in serving Othello. His language is also revealing of his dark character; he uses the cliché "I will wear my heart upon my sleeve" to convey how his heart is false, and his shows of emotion are also falsified (64). But, he turns this cliché into something more dark and fierce, when he adds the image of the birds tearing at this heart; already, he has foreshadowed the great deceptions that he will engineer, and the sinister qualities that make up his core. The key to Iago's character is in the line "I am not what I am"; Roderigo should take this as a warning, but fails to. Everything which Iago presents himself as is a false show; even here, he pretends to be less evil than he truly is, though this first scene represents the peak of Iago's honesty about himself with another character. Iago is parallel to another character, Richard III, in his self-awareness about his villainous character, and in his also parallel lack of remorse and use of false representations of himself. Already, the racial issues and themes which are at the core of Othello's story and position are beginning to surface. When Roderigo refers to Othello, he calls him "the thick lips"; the synecdoche, singling out one prominent characteristic that highlights Othello's foreignness and black heritage, displays a racial distrust of Othello based on his color. Roderigo and Iago are not the only characters to display racism when referring to Othello; racism is a pervasive theme within the work, spreading misconceptions and lies about Othello by tying him to incorrect stereotypes about his race. Another element that surfaces repeatedly in the play is the use of animal imagery; "an old black ram is tupping your white ewe," Iago yells to Brabantio from the street (88-9). The use of animal imagery is used in many places in the play to convey immorality, almost bestial desire, and illicit passion, as it does in this instance. Iago also compares Othello to a "Barbary horse" coupling with Desdemona, and uses animal imagery to reinforce a lustful picture of Othello, before this scene is through. Iago's statement is doubly potent, since it not only condemns Othello for his alleged lust, but also plays on Brabantio's misgivings about Othello's color, and outsider status. The juxtaposition of black and white, in connection with the animal imagery, is meant to make this image very repellent, and to inflame Brabantio to anger and action. Iago especially mentions the devil many times in the text, the first time here in the first scene. He means to make Othello sound like a devil, with his lust, indiscretion, and strangeness to Venice; the irony is that Iago is so quick to make others out to be evil, when it is he who is the center of blackness and foul deeds in the play. The devil often takes disguises, just as Iago does; he is as close to a devil as there is in this play, though, again embodying the theme of appearance vs. reality, he is the one who looks least guilty. Important to this scene is the fact that it is held in darkness; like the beginning of Hamlet, things are unsteady and eerie, and a certain disorder rules over the proceedings. With Brabantio's call for light, there is a corresponding call for some kind of order; darkness vs. light and order vs. disorder are important juxtapositions within the play, and as themes they highlight the status of situations like this one. This theme will appear again at the end, as the play returns to darkness, and also to chaos; the two seem inextricably linked in the body of the play, and always battle with one another. Act I, scene ii: Summary Iago has now joined Othello, and has told Othello about Roderigo's betrayal of the news of his marriage to Brabantio's daughter. He tells Othello that Brabantio is upset, and will probably try to tear Desdemona from him. Cassio comes at last, as do Roderigo and Brabantio; Iago threatens Roderigo with violence, again making a false show of his loyalty to Othello. Brabantio is very angry, swearing that Othello must have bewitched his daughter, and that the state will not decide for him in this case. Othello says that the Duke must hear him, and decide in his favor, or else all is far from right in Venice. Act I, scene ii: Analysis Iago continues his deliberate misrepresentation, swearing to Othello that he could have killed Roderigo for what he did. Iago, however, is a very skilled actor; he is able to successfully present a contrary appearance, and get away with it. Ironically, Iago alludes to Janus, the two-faced god, in his conversation with Othello. Since Iago himself is two-faced, in a duplicitous way, Janus seems to be a fitting figure for Iago to invoke. Iago's duplicity is again exhibited in this scene as his tone swings from friendly to backbiting as soon as Othello steps away, and then he goes back to his original friendliness when Othello returns. Whereas Iago acted supportive of Othello's marriage to Desdemona, when Cassio enters, he uses a rather uncomplimentary metaphor to tell what Othello has done. "He tonight hath boarded a land-carrack," Iago tells Cassio; his diction and choice of metaphor make Othello into some kind of pirate, stealing Desdemona's love, and reduces Desdemona into a mere prize to be taken. But, this tone is carefully calculated; Iago will soon want Cassio to think of Desdemona as an object to be taken, and to believe Othello to be less honorable than he is. Othello's pride first becomes visible here; he is exceptionally proud of his achievements and his public stature, and pride is an overarching theme of Othello's story. He is also proud of Desdemona's affection for him, which leads him to overstate the bond between them; he would not give her up "for the seas' worth," he says, certainly a noble sentiment (l. 28). Othello is very confident in his worth, and in the respect he commands; if the leaders of the city decide to deny a worthy man like him his marriage to Desdemona, then he believes "bondslaves and pagans shall our statesmen be." This statement of paradox betrays Othello's faith in the state and in the Duke's regard for him; hopefully, neither will fail him. Again, the issue of race comes to the fore, as Brabantio confronts Othello about his marriage to Desdemona. Desdemona never would have "run from her guardage to the sooty bosom of a thing such as thou," Brabantio says (l. 71-2). Brabantio assumes that Desdemona must have been "enchanted" to marry Othello merely because Othello is black; Brabantio ignores all of Othello's good qualities, and gives into his racist feelings. Magic is another recurrent theme, and here is linked to stereotypes of African peoples as knowing the black arts of magic, of being pagans, and of being lusty; the theme of magic does not always play into the theme of race within the play, though here there is an interesting relation of the two due to racial stereotyping. At the time Shakespeare was writing, there were in fact free blacks in England, with some art of the period depicting black peoples. However, racism was even more pronounced in Shakespeare's England than it is in Othello; a character like Othello could not have risen to such ranks in England at the time, which means that Shakespeare's play is much more progressive than the time in which it was written. Othello even manages to avoid stereotype more effectively than another Shakespearean character like Shylock, who represents anti-Semitic views of the Jewish people; stereotypes are linked to Othello by other characters, but he manages to evade them through his nobility and individuality. Act I, scene iii: Summary Military conflict is challenging the Venetian stronghold of Cyprus; there are reports that Turkish ships are heading toward the island, which means some defense will be necessary. Brabantio and Othello enter the assembled Venetian leaders, who are discussing this military matter, and Brabantio announces his grievance against Othello for marrying his daughter. Othello addresses the company, admitting that he did marry Desdemona, but wooed her with stories, and did her no wrongs. Desdemona comes to speak, and she confirms Othello's words; Brabantio's grievance is denied, and Desdemona will indeed stay with Othello. However, Othello is called away to Cyprus, to help with the conflict there; he begs that Desdemona be able to go with him, since they have been married for so little time. Othello and Desdemona win their appeal, and Desdemona is to stay with Iago, until she can come to Cyprus and meet Othello there. Roderigo is upset that Desdemona and Othello's union was allowed to stand, since he lusts after Desdemona. But Iago assures him that the match will not last long, and at any time, Desdemona could come rushing to him. Iago wants to break up the couple, using Roderigo as his pawn, out of malice and his wicked ability to do so. Act I, scene iii: Analysis Brabantio again accuses Othello of bewitching his daughter, and airs his racism-based views. He is not against the match because of any incompatibility of the couple; he thinks that nature has made some mistake, because of the mixed race of the couple. His metaphor of his grief as a flood, that "engluts and swallows other sorrows, and is still itself," means that he feels very strongly on this issue. His strong objection foreshadows a confrontation between him and his daughter; and, if Desdemona does choose to stay with Othello, it seems likely that she will risk her father's love. Othello's appointment to Cyprus marks the true beginning of his tragedy; for, when he is away from Venice, which is a place of familiarity, order, and law, he will be much more vulnerable to Iago's vicious attacks on his love and jealousy. This battle between order and chaos is a theme running throughout the play, and as Othello sinks deeper into distrust of Desdemona and is more consumed by his jealousy, chaos increases and threatens to devour him. The Duke's words of advice to the couple also mark the beginning of their tragic story; the Duke's words foretell trouble between the couple if they do not let grievances go, which ends up being a reason for Othello's fall. Also, the change of the verse into couplets signals the importance of the advice being offered. The words of the Duke, and Brabantio's words that follow, are set off from the rest of the text and emphasized by this technique; the reader is notified, through the couplet rhyme, which hasn't appeared before in the text, that these are words that must be marked. Although Othello pretends to be poorly spoken, the only magic that he possesses is in his power of language. His language shows his pride in his achievements, and also allows him to make himself into a kind of hero. Othello portrays himself as a tested, honorable warrior, and indeed is such. However, this view of himself will prove troublesome when he is hard pressed to recognize his jealousy and his lust; his inability to reconcile himself with these two aspects of his personality means that his comeuppance is almost certain. Othello's lack of self-knowledge means that he will be unable to stop himself once Iago begins to ignite his jealousy, and set into motion the less palatable aspects of Othello's personality, which he himself cannot recognize. Othello's speech before the assembly shows what he believes Desdemona's love to be; he thinks that Desdemona's affection is a form of heroworship, and she loves him for the stories he tells, and the things he has done. He believes it is his allusions to strange peoples and places, like the "Anthropophagi," that fascinate her, and this youthful fascination forms the semi-solid core of her affections. Indeed, his powers of language successfully win the Duke over, and soften Brabantio's disapproval. Light and dark are again juxtaposed in the Duke's declaration to Brabantio, that "if virtue no delighted beauty lack/ your son-in-law is far more fair than black." Black is associated with sin, evil, and darkness; these negative things are also associated to black people, merely because of the color of their skin. The Duke's statement is ironic, since Othello is black, but truthful, because his soul is good and light. Light/white/fairness all convey innocence, goodness, etc.; any symbol that is white has these qualities. The juxtaposition of black and white, light and dark shows up again and again in the play, as the colors become symbolic within the story. "Our bodies are our gardens," Iago tells Roderigo; his speech recalls Hamlet's first soliloquy, though with a more kind appraisal of human nature. Iago is a very good judge of human nature, and easily able to manipulate people in ways that will benefit him most; but, this cleverness also means that he is a source of wisdom in the play, no matter how wickedly he chooses to use this knowledge. Iago's metaphor is particularly applicable to many in this play, himself excluded; characters like Othello, Roderigo, and Cassio do have vices that they allow to grow in themselves, but they also have aspects of themselves which balance these vices out. Iago's knowledge of this allows him to do away with this balance and set chaos into motion, which leads to tragedy. Here, Iago's purpose becomes plain; he sees that Othello and Desdemona's marriage is less than solid, and seeks to use his powers to break this marriage apart. Iago is again "honest" about his intent, but only to a person whose involvement will help him greatly. The words "honest" and "honesty" appear repeatedly in the play, and are usually used by Iago, or in reference to him; ironically, Iago is the only person in the play whom Othello trusts to judge who is and is not honest, and the only one whose integrity is not questioned until it is too late. Honesty becomes an important question, and theme, in the story; characters repeatedly ask themselves who is honest, who can be trusted, and Iago indeed plays on their honesty to make them believe falsely. The word "honest" is often used in an ironic context, or indicates that someone or something cannot be trusted, if they are given this title. Under Iago's influence, honesty becomes a difficult liability, and speeds the downfall of many good characters.