The nature of contraries in Blake`s Songs of

advertisement

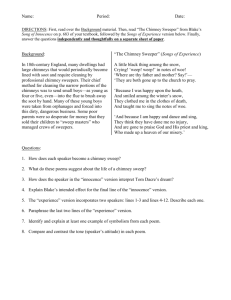

Rachel Burns Dr Gonda The ‘Contrary States’ of Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience Blake’s chosen subtitle explicitly terms the explored qualities of ‘innocence’ and ‘experience’ as ‘the two contrary states of the human soul’. The word ‘contrary’ is of great significance here; for in defining each condition in its opposition to the other (its ‘contrariness’), Blake implies their dissimilar and exclusive natures. The concept of exclusivity is particularly important as it suggests a dualistic approach in which the two states do not overlap and therefore an individual can only be either innocent or experienced and not both. This split mimics other opposing pairs, widely held in moral thought of the time, of which a human can only ever, at one given time, correspond to half; life and death, good and evil, heaven and hell - or in terms of human form - each aspect was often considered mental or material. Blake’s initial separation of innocence and experience then, indicates a rather strict independence on each part – it is of interest to determine whether the two representative sets of poetry reflect and maintain this division. An introduction accompanies each collection, prefiguring the poems to come by setting a tone, providing a taste and summarising an attitude towards each state, giving us a sense of how they are to be represented. This ‘sense’ is imparted by poetic elements used to embody the abstract concepts of innocence and experience and are on the whole, well suited to their respective conditions. We may observe in the introduction to the poems ‘of experience’, for example, a certain air of confidence and an unquestioned belief that the narrator is justified in making judgements; there are exclamations and commands, ‘Hear the voice of the Bard!’ (line 1) – neither of which are seen in the unknowing, unassuming voice of the introduction to ‘innocence’, ‘Piping down the valleys wild.’ (1) The narrator of the ‘innocent’ introduction instead finds himself blindly accepting and following orders without a thought to question authority or the value of the ideas proposed ‘…he laughing said to me./ Pipe a song about a Lamb:/ So I piped with merry chear…’ (4-6) The introduction for ‘innocence’ is rendered almost entirely in the past tense, a simple retelling of an event that the narrator claims to have been the inspiration for the following poems. It is uncomplicated by multiple allusions to the future – there is only the hopeful wish for a universal and positive reception ‘Every child may joy to hear’ (20)– and the conditional ‘may’ fittingly prevents the confident, assuming tone of an experienced narrator. The report of the event is also largely composed of ‘matter- 1 Rachel Burns Dr Gonda of-fact’ statements bereft of judgement, ‘On a cloud I saw a child’ (3); the only implications of opinion are optimistic, celebrative, cheerfully recounting ‘songs of pleasant glee’ (2), ‘my happy songs’ (19). The implication is that with innocence comes optimism; this is particularly appropriate as in reading of a state of ‘innocence’ one assumes not only a lack of knowledge to be present but some form of purity, some untainted element - here the narrator is untouched by the negative cynicism that accompanies worldly experience. In suitable contrast, in the introduction to the Songs of Experience there appears to be an almost arrogant overestimation of ability – as if acquiring some experience has given the narrator reason to believe that he is within his right to give orders and invoke the entirety of time itself. He calls himself the ‘Bard’ (1) and claims sight that reaches to the ‘Present, Past and Future’ (2), boldly professing a knowledge that is all-encompassing – evoking notions of the sometimes haughty superiority that can be displayed by the experienced. We may also perceive an element of judgement that is not present in quite the same way in the introduction of innocence; the experienced narrator capitalises nouns, illustrating a judgement of their significance. We see this only once from the innocent narrator who alludes to the ‘Lamb’ (5); this is, however, a fairly obvious reference to Christ and therefore one would expect it to be capitalised out of respect and tradition. Some of the words in the introduction of experience are, on the other hand, not necessarily conducive to having a capitalised first letter (‘Bard’ (1), ‘Present, Past…Future’ (2) and ‘Soul’ (6)) and therefore appear to have been specifically selected out of a process of choice and judgement, for emphasis. In place of such bold assertions of authority and judgement the ‘innocent’ introduction furthers the sense of its own simplicity with the limited use of language- its vocabulary appears sparse, with repetitions of variations on the word ‘pipe’ and the recurrent uses of ‘song’ and ‘I’. This consistent use of the first person and repeated employment of the first person singular pronoun provides a frequent reminder of naivety – that without experience all one has to rely on is ones own perceptions as they stand. In the introduction to experience there is, conversely and most fittingly, more of a sense of awareness of things outside oneself; the narrator refers to textures and states of objects not necessarily immediately present, ‘dewy grass’ (12) and acknowledges the effects of time, referring to the ‘ancient 2 Rachel Burns Dr Gonda trees’ (5). In addition, rather than repeated self-referencing, the narrator refers to objects and concepts using the definite article ‘the’. This presupposes the reader’s knowledge of the noun, insinuating a developed awareness of the experience of others – an awareness that is, appropriately, not displayed by the ‘innocent’ narrator. It certainly appears that the literary techniques used in the introductions serve to create a particularly skilful embodiment of the respective qualities – there is something about reading them alongside each other that gives a real sense of the represented states of innocence and experience. Now, so as to determine whether these states are kept separate and independent within the body of the work we may observe whether the methods used in the introductions are kept exclusive to their relevant set of poems or whether there is a certain amount of overlap. ‘The Chimney Sweeper’, as it is written in Songs of Innocence, seems to hint at a considered perspective, appearing as an indirect comment on society formed upon experience and opinions. Although the overall message (if indeed there is one) seems, due to Tom’s prophecy or enlightenment, to be essentially positive and hopeful, there seems to be a strong, pessimistic undertone. An innocent mind would, unknowing and inexperienced, not conceive of the contrary to Tom’s optimistic dream of the ‘Angel’ yet there is a persistent sense of strife and suffering that, even after Tom’s glorious revelation, remains a prominent part of the poem right through to the end. We are reminded, at the song’s close, of the work and poverty the chimney sweepers have yet to endure, ‘with our bags & our brushes to work./ Tho’ the morning was cold…’ (22-3). In addition, the hope of salvation then, in a subtle but nonetheless potentially devastating and sombre twist, becomes dependent on the workers’ obedience to society ‘So if all do their duty, they need not fear harm’ (24). This conditional ‘if’ gives the poem a dark air of cynicism, which does not at all seem like the unassuming view of an innocent narrator. The implications of this cynicism are unclear – perhaps it suggests that it is possible to be innocent and also cynical. One could, following this suggestion, greatly lack in experience and be pure (in the sense that one does not hasten to condemn but generally gives the benefit of the doubt) but also have a certain amount of cynicism that is recognised to be more characteristic of an experienced individual. Perhaps 3 Rachel Burns Dr Gonda this pessimistic tone does not belong to the chimney - sweeper at all but to another narrator above him – to Blake perhaps, as the ‘experienced’ adult author. That he would allow his experienced influence to have any noticeable affect at all says something about his view of the nature of experience. Experience is possibly viewed as a corrupting force that refuses to leave innocence untainted; or perhaps it is that as an author who is experienced, Blake can never again fully achieve a state of innocence and this is portrayed in his poetry. We may also observe aspects of these ‘contrary states’ crossing over to their opposition in ‘Holy Thursday’, in which the pessimism of experience uncharacteristically (as far as its character is portrayed in the poems) fails to completely eclipse the element of hope. Both versions of ‘The Chimney Sweeper’ end with a rather ominous note; the first reminding the reader of the toil and strife yet to be endured by the unfortunate, innocent chimney sweepers and the second complaining of those (including the child’s parents) ‘Who make a heaven out of our misery’ (12). Experience as it is represented within the poems seems almost to be automatically accompanied by cynicism (which, as we have seen can even spill over into the world of innocence) yet the cynicism in this song is, rather oddly, suppressed by a surging feeling of hope: For where-e’er the sun does shine, And where-e’er the rain does fall: Babe can never hunger there, Nor poverty the mind appall. (13-6) This last thought is reminiscent of a biblical passage promising the salvation of heaven, ‘They shall hunger no more, neither thirst any more; neither shall the sun light on them, nor any heat’ (Revelation 7:16). The contrast, one will notice, is that the biblical excerpt places emphasis on a lack of bodily experience- noting, in particular, the absence of sunlight; whereas Blake’s lines specifically associate this spiritual liberation with the far-reaching qualities of the sun’s rays. It appears as though Blake is making a deliberate move away from the biblical prophecy but on closer reading, this seems unlikely to be the case. Despite the obvious difference between the positive and negative references to the presence of the sun, the general sense of the statements appears largely similar. Blake’s optimistic 4 Rachel Burns Dr Gonda allusion to sunlight serves to create a stark contrast with the earlier lamentation ‘And their sun does never shine’ (9). His appeal to the all-encompassing (earthly) qualities of ‘the sun’ and ‘the rain’ functions as an indication of universal and eternal vitality. It is this sense of the eternal, the unchanging, an exemption from bodily vulnerability, that the biblical statement seeks to capture; thus the two assertions seem to be urging in the same direction – towards a comforting promise of deliverance from worldly harms. Blake’s song of experience, therefore, positively invokes the Bible, generating forceful overtones of faith and hope, which conquer the pessimism seen to infect not only the experienced narrator but also his innocent counterpart. It seems that just as the cynicism of experience can bleed into innocence, the hope and optimism shown to accompany innocence can shine through the diction of an ‘experienced’ narrator. A close reading of only two of the songs from each ‘set’ has revealed an overlap between the states of innocence and experience that does not pertain to the strict separation implied by Blake’s labelling of them as ‘contrary’. This element of ‘overlap’ should not come as a surprise once we consider Blake’s own stance; he commits to neither of the states, standing outside both and exposing their inadequacy. He portrays innocence as too fanciful; in ‘Nurse’s Song’ (of Songs of Innocence) he envisages a world too carefree and whimsical to be true. The frolicking children plead for more play-time, ‘No no let us play, for it is yet day’ (9) and get the desired response ‘Well well go & play till the light fades away’ (13). The echoing of the ‘No no’ in the responding ‘Well well’ teamed with the full rhyme and matching metre produce a reply so perfectly suited (both in content and form) to the request that it seems constructed and false- far too good to be true. The concluding idyllic image further distances the events from reality ‘The little ones leaped & shouted & laugh’d/ And all the hills ecchoed’ (15-6). The children carry on without a care in the world; their wish was granted without any trace of difficulty and it all ends happily ever after. The portrayal is so simple in its perfection that it is rendered far too idyllic to represent anything like the state of society in reality. Blake seems to be mocking the naivety of innocence but this does not mean that he promotes a state of experience as preferable. The second version of ‘Nurse’s song’ reveals hideous tendencies of the ‘experienced’ to become pessimistic; the nurse’s jealousy of childhood makes her bitter towards the playing children The days of my youth rise fresh in my mind, / My face turns green and pale.’ (3-4). She resentfully remarks 5 Rachel Burns Dr Gonda ‘Your spring & your day, are wasted in play’ (7), illustrating how those with worldly experience can begrudge the untroubled existence of the naïve and through knowledge of injustice and suffering in society become critical and miserable. As Blake does not set about to endorse either state as the ideal, one may perhaps conceive of a depleted motivation to retain their exclusivity. As innocence and experience are essentially likened to one another in so far as he denounces both as flawed conditions – it is no great surprise that they are seen to share characteristics and that they are not quite so ‘contrary’ after all. 6