Romanticism - The Calverton School

advertisement

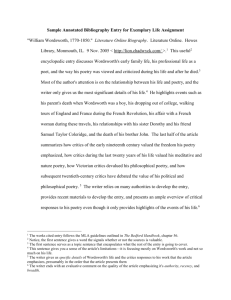

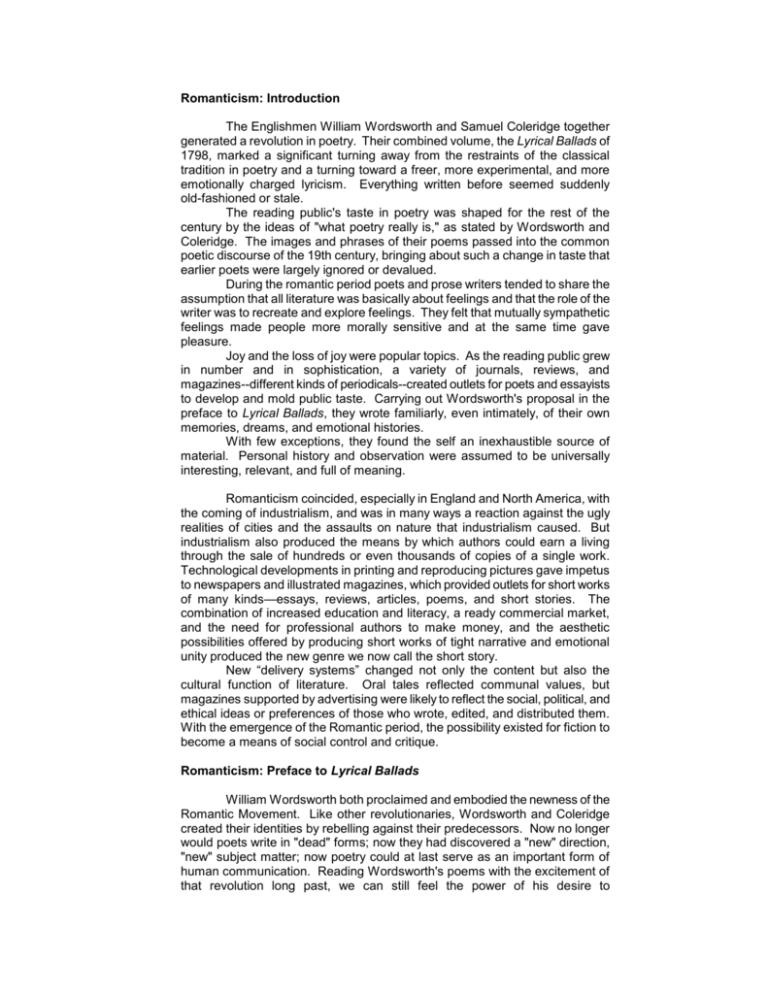

Romanticism: Introduction The Englishmen William Wordsworth and Samuel Coleridge together generated a revolution in poetry. Their combined volume, the Lyrical Ballads of 1798, marked a significant turning away from the restraints of the classical tradition in poetry and a turning toward a freer, more experimental, and more emotionally charged lyricism. Everything written before seemed suddenly old-fashioned or stale. The reading public's taste in poetry was shaped for the rest of the century by the ideas of "what poetry really is," as stated by Wordsworth and Coleridge. The images and phrases of their poems passed into the common poetic discourse of the 19th century, bringing about such a change in taste that earlier poets were largely ignored or devalued. During the romantic period poets and prose writers tended to share the assumption that all literature was basically about feelings and that the role of the writer was to recreate and explore feelings. They felt that mutually sympathetic feelings made people more morally sensitive and at the same time gave pleasure. Joy and the loss of joy were popular topics. As the reading public grew in number and in sophistication, a variety of journals, reviews, and magazines--different kinds of periodicals--created outlets for poets and essayists to develop and mold public taste. Carrying out Wordsworth's proposal in the preface to Lyrical Ballads, they wrote familiarly, even intimately, of their own memories, dreams, and emotional histories. With few exceptions, they found the self an inexhaustible source of material. Personal history and observation were assumed to be universally interesting, relevant, and full of meaning. Romanticism coincided, especially in England and North America, with the coming of industrialism, and was in many ways a reaction against the ugly realities of cities and the assaults on nature that industrialism caused. But industrialism also produced the means by which authors could earn a living through the sale of hundreds or even thousands of copies of a single work. Technological developments in printing and reproducing pictures gave impetus to newspapers and illustrated magazines, which provided outlets for short works of many kinds—essays, reviews, articles, poems, and short stories. The combination of increased education and literacy, a ready commercial market, and the need for professional authors to make money, and the aesthetic possibilities offered by producing short works of tight narrative and emotional unity produced the new genre we now call the short story. New “delivery systems” changed not only the content but also the cultural function of literature. Oral tales reflected communal values, but magazines supported by advertising were likely to reflect the social, political, and ethical ideas or preferences of those who wrote, edited, and distributed them. With the emergence of the Romantic period, the possibility existed for fiction to become a means of social control and critique. Romanticism: Preface to Lyrical Ballads William Wordsworth both proclaimed and embodied the newness of the Romantic Movement. Like other revolutionaries, Wordsworth and Coleridge created their identities by rebelling against their predecessors. Now no longer would poets write in "dead" forms; now they had discovered a "new" direction, "new" subject matter; now poetry could at last serve as an important form of human communication. Reading Wordsworth's poems with the excitement of that revolution long past, we can still feel the power of his desire to Romanticism 2 communicate. The human heart is his subject; he writes, in particular, of growth and of memory and of the perplexities inherent in the human condition. Although it had a mixed critical reception, the first edition of Lyrical Ballads was a "sellout." Two years later, in 1800, Wordsworth and Coleridge prepared a new, two-volume edition with additional poems, including the long narrative poem "Michael." Wordsworth also added an explanatory preface in which he defended the new type of poetry that he and Coleridge had put forth. It was this, Wordsworth's “Preface” of 1800 and, later, Coleridge's Biographia Literaria that were the manifestoes of the new aesthetic sense. From Wordsworth's “Preface” to 2nd Edition of Lyrical Ballads, 1800 “Taking up the subject, then, upon general grounds, let me ask, what is meant by the word poet? What is a poet? To whom does he address himself? And what language is to be expected from him?--He is a man speaking to men: a man, it is true, endowed with more lively sensibility, more enthusiasm and tenderness, who has a greater knowledge of human nature, and a more comprehensive soul, than are supposed to be common among mankind; a man pleased with his own passions and volitions, and who rejoices more than other men in the spirit of life that is in him; delighting to contemplate similar volitions and passions as manifested in the goingson of the universe, and habitually impelled to create them where he does not find them. To these qualities he has adds a disposition to be affected more than other men by absent things as if they were present; an ability of conjuring up in himself passions which are indeed far from being the same as those produced by real events, yet (especially in those parts of the general sympathy which are pleasing and delightful) do more nearly resemble the passions produced by real events than anything which, from the motions of their own minds merely, other men are accustomed to feel in themselves—whence, and from practice, he has acquired a greater readiness and power in expressing what he thinks and feels, and especially those thoughts and feelings which, by his own choice, or from the structure of his own mind, arise in him without immediate external excitement. 2 Romanticism 3 ----“I have said that [Romantic] poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings; it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility: the emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquility gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind. In this mood successful composition generally begins, and in a mood similar to this it is carried out….” Analysis: Wordsworth's “Preface” to 2nd Edition of Lyrical Ballads, 1800 Definition: "[Romantic] ... poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility: the emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquility gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind." A New Poetic Standard: The preface argues for a new poetic standard. Wordsworth rejected the neoclassical theory of poetry, which arranged the different kinds of literature in a hierarchy, each with its own appropriate subject matter and level of diction. Wordsworth particularly rejected the elevated poetic diction of the 18th century poets such as Thomas Gray, whose language was artificial and whose style was unnatural, based on reading rather than speech. Wordsworth proposed making poetry through the selection and arrangement of the sincere and simple language of the ordinary individual, adapting prose language to poetic uses. Thus Wordsworth undermined the dignity of poetry, but he also gave it a newer, broader scope that included a range of persons and situations never written about before--the humble and rustic life taken seriously. A New Role for the Poet: Wordsworth also redefined the role of the poet. The poet is merely "a man speaking to men," albeit one who has a greater than average sensibility and "knowledge of human nature." The poet's main qualifications are not in matters of craft or technique; he is a poet because his feelings allow him to enter sympathetically into the lives of others and to translate passions into words that please. "The poet thinks and feels in the spirit of the passions of men." It follows that poets must use the language of other men. A New Definition of Poetry: Poetry itself is redefined as "the spontaneous overflow of powerful feeling: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility." That 3 Romanticism 4 is, poetry is the outcome of a creative process. The poet thinks about an emotional experience "in tranquility," after the original moment of feeling has passed. But as he thinks, the emotion returns, and while under the influence of this renewed feeling, the poet begins to write the poem. Pleasure is the state in which the poetic composition is written, and pleasure is also found in the result. Wordsworth assumes that the reader of such poetry will share the poet's pleasure. At least, said Wordsworth, that is what he aims for in his poetry. Summary 1. The needs and rights of the individual transcend those of society at large. The individual is a law unto him or herself. The person of genius (particularly the artist) is above ordinary mortals; and unrestrained self-expression is the right of everyone, particularly the artist. 2. Emotion, not reason, is the path to true understanding and wisdom. Moreover, strong emotions, especially feelings of the sublime and eternal, are good to seek and cultivate for their own sake. Experience is best understood subjectively, not objectively. 3. Communion with nature—especially nature unspoiled by humans— is a source of true feeling, a guide to moral conduct, and a vehicle for encountering the transcendent or divine. Moreover, a life close to Nature is preferable to one in the “artificial” city. 4. People are by nature good, and evil results from social influences and repressions—hence, the idea of the noble savage, unspoiled by civilization, and a fascination with “primitive” people. 5. Imagination and originality, not restraint and tradition, are the key ingredients in any work of art. 6. The remote, the exotic, the medieval, the strange (including strange, warped, or dreamlike emotional or psychological states) are valued over the ordinary realities of daily life. 7. Stylistically, Romanticism prefers lush exuberance to decorum, restraint, and simplicity. Romantic prose is often rich with description; it tends toward abstract words like “tremendous” and “gorgeous”; it chooses and uses words for their maximum emotional effect. 8. The ideal, imaginary, and visionary are more important and more “real” than the mundane facts of daily life; by creating the ideal, artists become, as Shelley said, “the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” 9. There is a new concept of poetry: "the spontaneous overflowing of powerful feelings...recollected in tranquility." 4