April 11: The Tale of Sir Thopas, The Tale of Melibee, The Monk`s

advertisement

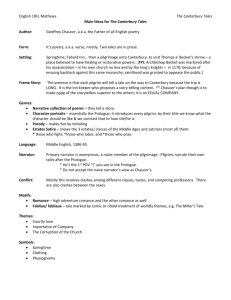

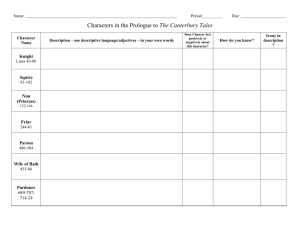

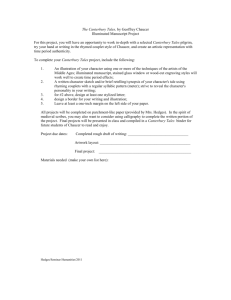

English 4160: CHAUCER University of Wyoming/Casper College Center; Spring 2011; Monday 4-7; AD 171, Instructor: Bruce Richardson (Ph.D., U.C.L.A.), Senior Lecturer of English, The University of Wyoming. Office: AD 178, Office Hours: Monday 2-3, Wed 2-4 and by appointment or accidental encounter; I am at home most mornings and in my office most afternoons. Give me a call. I am sometimes in meetings or out of town for academic and service work. Leave me a message and I will get back to you as soon as I can. Office: 268-2393; home: 237-4429; E-mail: brichard@uwyo.edu Required Texts: Benson, Larry, Ed. The Canterbury Tales: Complete. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2000. Recommended: Cooper, Helen. Oxford Guides to Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales. Second Edition. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1997. Other Recommended Supplements: Bessinger, J.B. Poems by Geoffrey Chaucer at audible.com Boitani, Piero and Jill Mann, Eds. The Cambridge Chaucer Companion. Cambridge Univ. Press, 1987. Howard, Donald. Chaucer: His Life, His Works, His World. New York: Ballentine, 1987. Knapp, Peggy. Chaucer and the Social Contest. New York: Routledge, 1990. Richard Schoeck and Jerome Taylor, eds. Chaucer Criticism: The Canterbury Tales. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1960. Web Resources: General guide to different high-quality resources http://english.edgewood.edu/430/430resc/htm Harvard site that supplements our text http://courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/ Selection of audio readings of Chaucer http://academics.vmi.edu/english/audio/audio_index.html The General Prologue and Physician’s Tale (audio download, $9.44) at audibile.com SCHEDULE January 24: Introduction; General Prologue. January 31: General Prologue. February 7: The Knight's Tale. February 14: The Miller's Tale, The Reeve's Tale, The Cook's Tale. February 21: President’s Day February 28: The Man of Law's Tale, The Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale. Name of outside reading due; begin language practice sessions. March 7: Wife of Bath’s Tale; The Friar’s Tale, The Summoner’s Tale; March 14: Spring Break March 21: The Clerk’s Tale, The Merchant’s Tale. Summary of outside reading due; schedule recitation. March 28: The Squire's Tale, The Franklin's Tale,The Physician's Tale; list of sources for term paper due. April 4: The Pardoner's Tale, The Shipman’s Tale, The Prioress’s Tale April 11: The Tale of Sir Thopas, The Tale of Melibee, The Monk’s Tale, The Nun’s Priest’s Tale. April 18: Second Nun’s Tale, Canon-Yeoman’s Tale, Manciple’s Tale. April 25: Parson's Tale, Chaucer's Retraction. Draft of term paper due; inclass editing. May 2: Review. May 9: Final Exam. REQUIREMENTS 1. Read in Middle English The Canterbury Tales, introductions and other supporting materials in The Complete Canterbury Tales and other assigned works and be prepared to discuss them in class. 2. Demonstrate your knowledge of Middle English by reciting from memory the first eighteen lines of The Canterbury Tales and reading aloud any other forty lines. 3. Read a book on the Middle Ages and write a two-page, single-spaced summary of material from the book that might help us understand Chaucer. 4. Write short, informal thought pieces, generally about one a week. 5. Do in-class interpretation/paraphrase exercises. These require you to understand Middle English and rephrase it in modern English. 6. Become an expert on one of The Canterbury Tales. Study the tale carefully, read as much about it as you can (at least six essays published after 1985), and develop your own interpretation. Be ready to provide substantial help to the class during our discussion of the tale and write a paper in which you summarize critical opinion on the tale and provide your own interpretation. You may do this assignment as part of a team that works on related tales or the same tale. Papers may be co-authored or submitted individually, but, in either case you will be part of a writing group that will act as an editor and boost to each other's papers-inprogress. 6. Take a final exam in which you demonstrate your knowledge of the course material by paraphrasing, identifying and commenting on specific passages from The Canterbury Tales and writing essays. Evaluation: Paper 30% Final 20% Recitation 10% Summary of Outside Reading 10% Short Papers and Paraphrases 15% Participation (including attendance) 15% TRANSLATIONS? This course requires that you read and understand The Canterbury Tales in the language Chaucer used--Middle English. This language is fundamentally the same as ours, but differing always in pronunciation, sometimes in vocabulary and often in syntax. These differences will take some adjustment and work on our part. Expect early frustrations and slow going that will disappear as you get familiar with this language. The assignments in Middle English are short and allow you time to read slowly, make notes and re-read, an essential activity in this class. I do not recommend using translations. They slow down your ability to learn the language, destroy the sound, mangle the poetry and distort the meaning. Often you will see the nuances and multiple meanings that Chaucer builds into words narrowed and lost by the translator's choice of a roughly equivalent modern word. Despite this, I know that some will use translations, but keep them out of your papers and the class discussion and under no circumstances use them as a substitute. You will be unable to pass the class if you do. RECOMMENDATIONS 1. Use the Casper College, UW/CC Writing Center often. The peer tutors can help you with brainstorming, getting first drafts going, revising papers, beating writer's block and other matters. 2. Use the University of Wyoming Library and inter-library loan. Right inside the Goodstein Library are computer terminals that connect you to a gigantic catalogue at Coe Library at the University of Wyoming and also other larger libraries. Given that the Goodstein Library and Natrona County Library have very tiny collections with almost nothing on Chaucer it is imperative that you use Interlibrary Loan and document delivery. Make use of the bibliographies in our text, the bibliographic essays in the Oxford Guide to Chaucer and the Modern Language Association annual bibliographies in finding secondary sources on Chaucer. There are materials online. Use these as you wish, but be sure that you refer to only peer-reviewed articles for your term paper. POLICIES 1. Late papers are accepted with a penalty of half a grade for each day overdue. 2. In my judgment, attendance and participation in this class are central to your learning as well as to the learning of all the rest of us in the class, including me. Accordingly, attendance will be graded and I reserve the right to lower the course grade for anyone who misses two classes. 3. Those who submit a plagiarized paper receive an "F" in the class and are reported to the Dean for disciplinary action. According to the "Style Sheet" from the UCLA English Department, "plagiarism is the use of another's ideas or words as if they were one's own" (5). Be sure to acknowledge any borrowed ideas or quotations. If you have questions about difficult cases, see me. Be alerted that I have access to a service that identifies work plagiarized from publications, web sites and paper mills. Works Cited: Department of English, UCLA. "Style Sheet." (1974). A PHILOSOPHY FOR THE CLASSROOM I subscribe to (pardon the clichés) a student-centered, active learning model. In my view, class sessions are collective enterprises that use argument, discussion, analysis, description and humor to create knowledge. I am willing to argue that knowledge is not some pre-existing construct available from, say, a textbook, a professional article or a lecture, but is part of an ongoing process to describe and explain the world. Textbooks, articles, lectures are part of a continuing conversation or argument among scholars, students, readers, writers, journalists, whomever to create, not discover, knowledge. In this class I want you to learn how to participate in the conversation, how to be a part of the process of knowledge creation and how careful (and not so careful) thinkers reach judgments about cultural documents. Members of a class ought not to be passive receptacles of one person's conclusions, but participants in the exercise of reaching conclusions. I hope you learn not what to think, but how thinking works, how to draw judgments, how to respond more fully to the world and the things in it. You will learn in this class that there are many, many ways to respond to cultural objects--because they are so complex, because they exist in so many contexts and because we readers are so complex and diverse. I plan to run this class as a discussion-seminar with lots of writing and small group work. Lectures may break out, but they will be accidents or responses to immediate issues. The best research thus far shows that people LEARN ALMOST NOTHING from sustained lectures, but do much better with discussion and writing in a participant, experience-based educational environment. We will use mostly discussion: talk, talk, talk, write, talk, talk, write, talk, draw, talk, write. Your notes should record the flow of conversation in the class and the judgments and arguments of the different class members. Views expressed during our sessions will form part of the final exam. Sometimes I will ask you to write a brief summary of the most important points made during the class. Keep a log of these. Listening carefully to others and reflecting on what they say are important skills in our enterprise. Finally, I have become convinced that people learn to write best in groups. Writing, so often a lonely effort with one struggling soul and one ominous judge, needs to go public. Drafts, notes, ideas, texts all should pass through a stream of hands and receive a multitude of responses. In the "real" world of professions, papers are done by many, for many. Only in schools is it otherwise. (Fortunately, this is changing and changing fast!) Process, process, process. No piece of writing is ever finished; no text is ever perfect, but it can get stronger along the way through the kindness of strangers and the help of friends. Consequently, in this class writing will be done collaboratively, in groups, with the aid and insight of others strengthening your work. I'll help you get the groups going and show you some ways of operating, but you might start seeking out partners. I know, in advance, that there is a lot of talent in this class and that you have much to teach each other and much to teach me. MY STUDY OF CHAUCER I took my first full Chaucer class at U.C.L.A. from Henry Ansgar Kelly, a new teacher and an historical scholar with a wide range of knowledge, partly from his training as a Jesuit priest. He has published many vigorous and iconoclastic books on the Middle Ages and Renaissance, including one arguing that Courtly Love was very much a literary fiction and not a set of practices. I took many undergraduate classes (and audited a Chaucer class) from Richard Lanham, a student of E. Talbot Donaldson at Yale and very much taken with the dramatic theory of the Canterbury Tales. His own major writing on Chaucer applies the principles of game theory and rhetorical strategy to Chaucer's comedy. An undergraduate seminar in allegory taught by E. I Condren covered Chaucer. Condren has published on sexual puns and subtexts in the Tales. I knew Florence Ridley, U.C.L.A.'s major Chaucerian well through work on committees and attended some of her lectures. For Lanham I wrote a long paper on William Blake's picture of the Canterbury pilgrims and for Kelly a paper on the significance of revenge in The Reeve's Tale. In graduate school I focused on English literature and art of the late 18th and early 19th centuries and issues of art and literature, not Chaucer. I was hired to teach English for the University of Wyoming program in Casper in 1984 and taught my first Chaucer class in 1985. The class went well and so I continued to teach Chaucer every so often. I have been aided by Susan Aronstein, a medievalist in Laramie, attendance at a conference devoted to Chaucer's religious tales, attending Chaucer sessions at other conferences, reading lots of secondary literature and listening carefully to my students as well as studying the secondary literature they use in their term papers. Currently, I think the study of Chaucer is valuable for sheer pleasure, but also because such study engages us in multiple approaches to literature. As such, it is a good place to learn about critical theories and methods of reading and analysis. My own bias is toward historical analysis that sees literary works as participants in arguments about religion, economic life, gender roles, politics and the like. Literature does not so much reflect social conditions and beliefs, but actively creates them or more exactly makes arguments about them. We see in Chaucer evidence of clashes over who will control the resources of the future, which include the body and interior life of the individual. In Chaucer’s time the principles of subordination of the individual to the communal whole (promoted by a steadily fragmenting Church) are challenged by the explosive dynamics of capitalism and the rise of individualism. If you want to follow some of my own current trains of thought look at Peggy Knapp's book, Stephen Knight’s Geoffrey Chaucer (Basil Blackwell, 1986) and David Wallace’s Chaucerian Polity (Stanford, 1997).