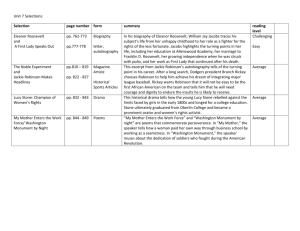

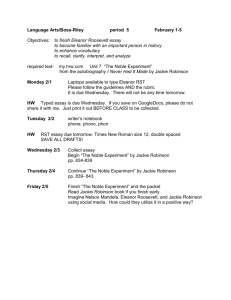

Overview - Walnut Creek School District

advertisement

Biography http://www.jackierobinson.com/about/bio.html Jack Roosevelt Robinson was born in Cairo, Georgia in 1919 to a family of sharecroppers. His mother, Mallie Robinson, single-handedly raised Jackie and her four other children. They were the only black family on their block, and the prejudice they encountered only strengthened their bond. From this humble beginning would grow the first baseball player to break Major League Baseball's color barrier that segregated the sport for more than 50 years. Growing up in a large, single-parent family, Jackie excelled early at all sports and learned to make his own way in life. At UCLA, Jackie became the first athlete to win varsity letters in four sports: baseball, basketball, football and track. In 1941, he was named to the All-American football team. Due to financial difficulties, he was forced to leave college, and eventually decided to enlist in the U.S. Army. After two years in the army, he had progressed to second lieutenant. Jackie's army career was cut short when he was court-martialed in relation to his objections with incidents of racial discrimination. In the end, Jackie left the Army with an honorable discharge. In 1945, Jackie played one season in the Negro Baseball League, traveling all over the Midwest with the Kansas City Monarchs. But greater challenges and achievements were in store for him. In 1947, Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey approached Jackie about joining the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Major Leagues had not had an African-American player since 1889, when baseball became segregated. When Jackie first donned a Brooklyn Dodger uniform, he pioneered the integration of professional athletics in America. By breaking the color barrier in baseball, the nation's preeminent sport, he courageously challenged the deeply rooted custom of racial segregation in both the North and the South. At the end of Robinson's rookie season with the Brooklyn Dodgers, he had become National League Rookie of the Year with 12 homers, a league-leading 29 steals, and a .297 average. In 1949, he was selected as the NL's Most Valuable player of the Year and also won the batting title with a .342 average that same year. As a result of his great success, Jackie was eventually inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962. Jackie married Rachel Isum, a nursing student he met at UCLA, in 1946. As an African-American baseball player, Jackie was on display for the whole country to judge. Rachel and their three children, Jackie Jr., Sharon and David, provided Jackie with the emotional support and sense of purpose essential for bearing the pressure during the early years of baseball. Jackie Robinson's life and legacy will be remembered as one of the most important in American history. In 1997, the world celebrated the 50th Anniversary of Jackie's breaking Major League Baseball's color barrier. In doing so, we honored the man who stood defiantly against those who would work against racial equality and acknowledged the profound influence of one man's life on the American culture. On the date of Robinson's historic debut, all Major League teams across the nation celebrated this milestone. Also that year, on United States Post Office honored Robinson by making him the subject of a commemorative postage stamp. On Tuesday, April 15 President Bill Clinton paid tribute to Jackie at Shea Stadium in New York in a special ceremony. Fast Facts http://www.jackierobinson.com/about/facts.html Birth Name: Jack Roosevelt Robinson Also known as: Jackie Robinson Birth Date: January 31, 1919 in Cairo, GA Death Date: October 24, 1972 in Stamford, CT Married: Rachel Issum on February 10, 1946 Children: Jackie Jr. (died in 1971), Sharon and David Height: 5' 11" Weight: 204 lb. Batted: Right Threw: Right College Education: UCLA Professional Team: Brooklyn Dodgers Years Played: 1947-56 Debut: April 15, 1947 Stats on Jackie Robinson >> Facts In 1982, Jackie Robinson became the first Major League Baseball player to appear on a US postage stamp. Jackie Robinson was 28 years old when he broke into the Major Leagues, yet he still won the unified Rookie of the Year Award. Fifty years after he became the first modern black player, Major League baseball chose his number as the first one to ever retire for every team. In 1949, Jackie Robinson led the National League in stolen bases and batting average, was named to his first All-Star Game, helped the Brooklyn Dodgers win the pennant by one game, and was named the years Most Valuable Player. Jackie Robinson's older brother Mack finished second to Jesse Owens in the 100-meter race in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. An outstanding athlete, Jackie Robinson was the first ever four-sport letter winner at UCLA (football, track, basketball and baseball). His accomplishments outside of baseball included leading the Pacific Coast Conference (later the Pac-10) in scoring twice in basketball, becoming the NCAA champion in 1940 in the broad jump (25 feet, 6.5 inches), and achieving All-American status in football. Shortly before his death, Jackie Robinson was selected to throw out the first pitch at the 1972 World Series, the 25th anniversary of his breaking Major League Baseball's color barrier. Overview CMG Worldwide is the exclusive business representative for the Estate of Jackie Robinson. We work with companies around the world who wish to use the name or likeness of Jackie Robinson in any commercial fashion. The words and the signature "Jackie Robinson" are trademarks owned and protected by the Estate of Jackie Robinson. In addition, the image, name and voice of Jackie Robinson is a protectable property right owned by the Estate of Jackie Robinson. Any use of the above, without the expressed written consent of the Estate, is strictly prohibited. http://www.jackierobinson.com/business/index.html Jack Roosevelt Robinson broke the color barrier in major league baseball; on April 10, 1947, Branch Rickey, president of the Brooklyn Dodgers, announced that Robinson had signed with his team. As the first African American to play in the major leagues, Jackie Robinson became the target of vicious racial abuse. Recalling his first season with the Brooklyn Dodgers in his autobiography, Robinson described how he played the best baseball he could as torrents of abuse were heaped upon him, and the entire nation focused its attention on his game. Having established a "reputation as a black man who never tolerated affronts to his dignity," he now found it in himself to resist the urge to strike back. In the ballpark, he answered the people he called "haters" with the perfect eloquence of a base hit. In 1949, his best year, Robinson was named the league's Most Valuable Player, and in 1962 he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. He retired from the major leagues in 1956. "Life is not a spectator sport. . . . If you're going to spend your whole life in the grandstand just watching what goes on, in my opinion you're escaping your life." -- Jackie Robinson, 1964 Jackie Robinson continued to champion the cause of civil rights after he left baseball. Having captured the attention of the American public in the ballpark, he now delivered the message that racial integration in every facet of American society would enrich the nation, just as surely as it had enriched the sport of baseball. Every American President who held office between 1956 and 1972 received letters from Jackie Robinson expressing varying levels of rebuke for not going far enough to advance the cause of civil rights. Indifferent to party affiliation and unwilling to compromise, he measured a President's performance by his level of commitment to civil rights. Robinson's stand was firm and nonnegotiable. The letters reveal the passionate and, at times, combative spirit with which Robinson worked to remove the racial barriers in American society.. http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured_documents/jackie_robinson_letter/ The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration 1-86-NARA-NARA or 1-866-272-6272 http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/people/r/jackie_robinson/index.html The New York Times Company (NYSE: NYT), a leading global, multimedia news and information company with 2011 revenues of $2.3 billion, includes The New York Times, the International Herald Tribune, The Boston Globe, NYTimes.com , BostonGlobe.com , Boston.com, and related properties. The Company’s core purpose is to enhance society by creating, collecting and distributing high-quality news and information. A decade before Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott, two decades before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. proclaimed "I Have a Dream," a signature event in the struggle for racial equality unfolded far from Dixie. On the afternoon of April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson emerged as an inspiring figure in the civil rights movement when he became the first black man to play major league baseball in the 20th century, making his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers against the Boston Braves at Ebbets Field. Robinson's triumphs in the face of bigotry evoked a sense of pride among black people and forced the rest of America to consider anew the doctrine of white supremacy. --RICHARD GOLDSTEIN The following account of Jackie Robinson's life was written by his daughter, Sharon Robinson, an author and an educational consultant for Major League Baseball. Ms. Robinson has written several widely praised books about her father, including “Jackie’s Nine: Jackie Robinson’s Values to Live By”; “Promises to Keep: How Jackie Robinson Changed America”; and her new picture book, “Testing the Ice,” illustrated by Kadir Nelson. She is also a vice chair of the Jackie Robinson Foundation. On April 15, 1947, Jack Roosevelt Robinson stepped on to the grass of Ebbets Field as a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers and became the first African-American to play in modern Major League Baseball. The crumbling of baseball’s wall of segregation was a harbinger of the civil rights movement. It came a year before President Harry Truman integrated the military and seven years before the United States Supreme Court, in its historic Brown v. Board of Education decision, declared school desegregation unconstitutional. His Early and College Years The arrival of Jackie Robinson was a defining moment for baseball — and for America. Jackie Robinson was 28 when he broke down Major League Baseball’s 59-year color barrier. He was born Jan. 31, 1919, in Cairo, Ga., the grandson of slaves and the fifth child of his sharecropping parents, Mallie and Jerry Robinson. When Jackie was 6 months old, his father deserted the family. Unable to maintain the farm alone, Mallie and her five children — Frank, Mack, Edgar, Willa Mae and Jackie – crossed the country by train bound for Pasadena, Calif. As a young boy, Jackie got average grades in school but excelled at sports. His college years were legendary. At Pasadena City College, he beat his brother Mack’s record in the broad jump, was most valuable player on the football squad and was named by sportswriters as the greatest base runner on a junior college team. Afterward, at U.C.L.A., he led the Pacific Coast Conference in basketball scoring; he was the national champion in the long jump, an All-American halfback in football and a varsity shortstop in baseball. He was the first athlete at U.C.L.A. to letter in four sports in a single year. In Jackie’s senior year, he was introduced to a freshman, Rachel Isum. Rachel was a nursing student from a middle class Los Angeles family, determined to be the first in her family to graduate from college. Jackie dreamed of being a professional athlete. They were engaged while Rachel was still in college. While Rachel completed her nursing education, Jackie served in the Army and went on to play baseball for the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Leagues. Robinson and Branch Rickey He was playing for the Monarchs when Branch Rickey, president and general manager of the Dodgers, sent out his scouts to the Negro Leagues to look for the right man to pioneer what he considered his noble experiment — desegregating the major leagues. The scouts came back with long lists of talent, but they all talked about Jack Roosevelt Robinson. Rickey listened and did his own research before bringing Robinson in for a face-to-face meeting. That now historic meeting took place in Rickey’s Brooklyn office on Aug. 28, 1945. Rickey described the stressful conditions Robinson would face in the majors. Rickey took on the role of racist fans shouting angry insults, and a spiteful opponent spiking Robinson with metal cleats. He was testing Robinson’s strength of character and willingness to hold back his temper against verbal and even physical attacks. Robinson agreed to fight back with responses like a perfectly timed bunt, a hard line drive and stolen bases. Two months later, he signed with the Montreal Royals, a Dodgers farm team. Confidence in the Face of Segregation Four months later, Jackie and Rachel married and began a long trek across the country from California so that Jackie could report to the Royals’ training camp in Daytona Beach, Fla. On the way, they were bumped from flights and were barred from eating in the coffee shop at the bus station; they finished their trip on a segregated bus. Despite the humiliation, Jackie arrived at camp confident that he’d make it through the minor leagues and on to the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Robinsons were run out of Sanford, Fla. with threats of violence. They lived separately from the team in private homes in the black community. They ate their meals in black restaurants. The Royals had different experiences in each city; Syracuse, N.Y., was worse than Sanford. In Baltimore, there were threats of violence and a boycott if Robinson appeared on the field. The first game drew few fans. But as the Montreal-Baltimore series continued, the crowd’s mood changed. Jackie stole home during one game; the fans gave him a standing ovation. In his one season with Montreal, he won the batting championship with a .349 average, scored 113 runs and ranked second in the league in stolen bases — and the Royals won the pennant and the Minor League World Series. Arriving in the Majors Despite Jackie’s successes in 1946, the 1947 Major League Baseball spring-training season began without a black player on any team’s roster. Then, on April 10, the Dodgers played the Montreal Royals in the last game of the exhibition season. Jackie hit into a double play in the sixth inning. Right after that play, a history-making announcement was made: The Brooklyn Dodgers had purchased Jackie Robinson’s contract from the Montreal Royals. On April 15, Jackie Robinson stepped out of the Brooklyn Dodgers dugout, crossed first base and took his position as first baseman. He paused, hands resting on bent knees, toes pointed in, then stood, lifted his cap and saluted the cheering fans. The first year wasn't easy. There were taunts from the crowds, jeers and viciousness from other teams and even opposition from some teammates who reacted angrily to the idea of playing with a black man. A Baseball Great But at the end of his rookie season, Jackie led the league in stolen bases and sacrifice bunts, and was second in runs scored. He played in 151 of the 154 games, all at first base, and brought a new aggressive style to the game. The Dodgers won the pennant for the first time since 1941 (losing to the New York Yankees in the World Series). He was named Outstanding Rookie of the Year. Jackie Robinson went on to play 10 seasons. He was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 1949. Of his nearly 5,000 career at-bats, 51 percent were from the cleanup slot. The 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers won the World Championship. Jackie retired from Major League Baseball in 1956. On Jan. 23, 1962, Jack Roosevelt Robinson was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. His Home Life Jack and Rachel built a home in Stamford, Conn.; there they raised their three children: Jackie Jr., Sharon and David. After retiring from the game, Robinson became vice president of personnel for Chock Full O’Nuts. In addition to his roles as husband and father, he traveled the country, raised money for the NAACP, joined protest marches, supported political candidates, hosted radio shows, wrote newspaper columns and books, played golf and cut the lawn. In his lifetime and posthumously, Jackie Robinson was awarded high honors from civil and human rights organizations, religious groups and the United States government. Jack’s failing health was his biggest challenge. After he retired from baseball, he found out that he had diabetes. Fighting for Equality He spent his entire life fighting for equality. He won some battles and lost others. Jack Roosevelt Robinson lost his battle with health on Oct. 23, 1972. He once said, “A life is not important except for the impact it has on other lives.” Jackie Robinson: Desegregation Begins with a Baseball http://www.crf-usa.org/black-history-month/jackie-robinson © 2013 CRF-USA • Constitutional Rights Foundation, 601 South Kingsley Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90005, (213) 487-5590 Fax (213) 386-0459 | When the Dodgers decided to break the color barrier in the major leagues, they sent out scouts looking for the player who could do it. He would have to be tough, intelligent, and a great athlete. They found the right person in Jackie Robinson. Tough, Robinson played baseball as if it were war. Intelligent, Robinson attended college, rare among baseball players at that time. An incredible athlete, Robinson is the only person in U.C.L.A. sports history to letter (and star) in four sportsfootball, basketball, baseball, and track. Jack Roosevelt Robinson, the youngest of five children, was born in Georgia in 1919. His father left the family when Robinson was only one year old, so his mother moved the children from Georgia to Pasadena, Calif., where Robinson was raised. He attended John Muir High School and went on to Pasadena City College and UCLA. Robinson battled discrimination throughout his life. Growing up in a predominantly white neighborhood, he had to prove himself constantly. After college, he entered the stillsegregated Army during World War II. Stationed in the South, Robinson was arrested Front cover of Jackie Robinson comic book (issue #5). for refusing to go to the back of a bus. After Shows Jackie Robinson in Brooklyn Dodgers cap; the war, he decided to play baseball inset image shows Jackie Robinson covering a slide professionally. Since black players could not at second base. (Wikimedia Commons) play in the major leagues, Robinson started his baseball career in the Negro leagues, playing for the Kansas City Monarchs in 1945. He was 26 years old at the time. His biggest battle was yet to come. In 41 games with the Monarchs, he batted .345, with 10 doubles, four triples, and five home runs. His performance was so impressive that he caught the eye of a scout for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ general manager, was looking for a talented black player like Robinson. Rickey realized that an incredible pool of talent and skill was being wasted by not allowing blacks to play in the majors. He had decided it was time for baseball to change. The Dodgers knew that they were taking a huge risk. They could anger their fans, other teams, and even their own players. The player they chose would have to withstand abuse and discrimination and still become a star. He would have to withstand the pressure of knowing that if he failed, it would be a long time before any black played in the majors again. Rickey believed that Robinson was the right person for the job. In 1946, the Dodgers started Robinson out in Montreal, Canada, with their top minor-league team. Immediately accepted by his teammates and the fans in Montreal, he led the team to first place in its league. Montreal then played Louisville, Ken., for the minor league championship, the Little World Series. Jeered and booed in Louisville, Robinson did not play well in the first games. But then the teams went to Montreal. Angered at Robinson’s treatment in Louisville, the Montreal fans jeered and booed the Louisville players mercilessly. Robinson shone in the final games, and Montreal won the series. Long after the final out, fans stayed in their seats cheering, "We want Robinson! We want Robinson!" With his success at Montreal, the Dodgers called Robinson up to the majors for the 1947 season. Rickey and Robinson agreed that Robinson would not respond to any insults, threats, or taunts. He would fight with his baseball skills alone. As soon as the Dodgers announced that Robinson would play, the trouble began. Newspaper editorials debated whether Robinson was suitable to play in the majors. Some of his Southern teammates circulated a petition against Robinson playing. (Most of the team refused to sign it.) Outfielder Dixie Walker, a Southerner, asked to be traded. (He got his wish at the end of the season.) The Philadelphia Phillies threatened to boycott a game if Robinson played, but after the baseball commissioner threatened to ban the players from baseball, the boycott evaporated. People wrote him letters threatening his life as well as the lives of his wife and son, Jackie Jr. At games, fans at visiting ballparks screamed insults. Players tried to spike him when he slid into bases. Once in Chicago, when sliding head first into second base, the Cubs' shortstop kicked Robinson in the head. Pitchers tried to bean him at the plate. On the road, some cities would not allow Robinson to stay at the team's hotel. Often, restaurants would refuse to serve him, and he would have to eat his meals on the bus while his teammates ate inside. Robinson did receive some support. Brooklyn fans backed him. Many blacks attended games throughout the league to cheer him on. Within a month, he had won over all his teammates, including the Southerners. When fans or opposing players became particularly hostile, team leader. Pee Wee Reese would make a point of putting his arm around Robinson to show the team’s solidarity. And many people of all races applauded Robinson's courage. But most of all, Robinson succeeded because of how well he played. A threat to steal whenever on base, Robinson would unnerve pitchers. He led the league in stolen bases, scored 125 runs, and batted .297. His play helped the Dodgers win the National League pennant that year, and Robinson was voted Rookie of the Year. Robinson had remained silent the entire year. He had not answered any insults; he had not responded to any provocation; he had not spoken out against racism. He remained silent for another year. But in 1949, Robinson and Rickey agreed it was time for Robinson to speak his mind. When he did, his statements angered many players, owners, and fans throughout baseball. But their anger did not affect his play: He batted .347 and was voted the National League’s Most Valuable Player that year. Robinson continued to speak out against racism throughout his life. When he retired from baseball in 1956, his lifetime batting average was .311, and he had stolen home 20 times in his career. In 1962, he was voted into the Hall of Fame. Although his play on the field never showed it, the pressure he endured took its toll. Plagued with diabetes, blindness in one eye, high blood pressure, and heart trouble, Robinson died on Oct. 24, 1972, at the age of 53. The full impact he made on baseball and desegregation in this country can never be fully determined. His place in baseball's record books goes well beyond his statistics. His life and career helped change the nation's way of thinking. He opened the door for hundreds of great black athletes. But he probably achieved more. In 1948, President Truman ordered the armed forces to desegregate. In 1954, the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education outlawed “separate but equal” schools. The Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s fought against segregation. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 opened public facilities to all races. But the movement against segregation after World War II really began in 1947 with Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier in baseball. CRF is a non-profit, non-partisan, community-based organization dedicated to educating America's young people about the importance of civic participation in a democratic society. Under the guidance of a Board of Directors chosen from the worlds of law, business, government, education, the media, and the community, CRF develops, produces, and distributes programs and materials to teachers, students, and public-minded citizens all across the nation. Cracking a racist wall Jackie Robinson's historic impact Published Apr 19, 2007 12:14 AM On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson broke the so-called color barrier by becoming the first African American to play in Major League Baseball. On April 15, 2007, the 60th anniversary of this significant event, over 200 MLB players and some managers of all nationalities wore Robinson’s retired number 42 on their uniforms to honor him. The following are excerpts from an April 10, 1997, article written by Mike Gimbel on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Robinson joining the then Brooklyn Dodgers. Go to www.workers.org/ww/robinson.html to read the article in its entirety. Robinson’s entry into Major League Baseball had a momentous impact on the anti-racist struggle in the U.S. It even had an important effect on U.S. imperialism’s political status on the world stage. Jackie Robinson, perhaps the most exciting baseball player of his time, was more than a “mere” athlete who happened to be in the right place at the right time. Robinson grew up in Pasadena, Calif., a town so racist that it took until 1997 to officially acknowledge his accomplishments. Jackie Robinson went into the segregated U.S. Army, where he became an officer. But he was court-martialed for failing to sit in the back of the bus at a Texas army base. The case became a national political incident and the army was forced to dismiss the charges against him. Jackie Robinson Just as Robinson was no accidental figure, neither were those who chose him to break the color barrier. Nor was it accidental that Major League baseball was the arena for this historical event. In order to understand the event in its proper context, one has to understand the period in which it happened. The USSR had defeated Nazi Germany in World War II, and in doing so had liberated much of Eastern Europe from capitalist slavery. A huge liberation movement, led primarily by communist parties, was sweeping Asia. The Western powers, led by the U.S., were trying to break the workers’ movements in France, Italy and Greece, where armed resistance to fascism had been led by the communists. The imperialist powers would have loved to present this as a struggle between communism and “democracy,” but they had a big problem: They were seen as racist oppressors on the world stage. The Europeans still claimed most of the world as their colonies, and the U.S. was propping them up. The U.S. had its own colonial holdings in Puerto Rico and the Pacific. In addition, the South was ruled by the Ku Klux Klan, an organization no better than Germany’s Nazi Party. The South was solidly held by the Democratic Party, and no Democrat could get elected president without the support of racist “Dixiecrats.” In 1947, the civil rights movement had not yet begun. The U.S. military was still segregated and it would be seven more years before the “Brown vs. Board of Education” Supreme Court decision declared “separate but equal” schools to be unconstitutional. But many Black soldiers were returning home after having risked their lives abroad. They came back to racism, in the North as well as the South. Yet there was a completely different political current. The U.S. left and progressive movement was still very powerful. Communist Party membership hit its zenith in 1947. Mass May Day marches were held all over the country replete with red flags. The labor movement was involved in militant strikes and the left had a huge influence in it. The U.S. ruling class could not credibly portray itself as “leader of the free world” while being perceived as the open oppressor of a large portion of its own population. Something had to be done. Truman and the Dixiecrats President Harry S. Truman, however, dared not act without support from the Dixiecrats. The U.S. ruling class seemed trapped by this quandary. The politicians couldn’t find an answer to this problem, which was so vital to U.S. imperialism. Another way had to be found. Baseball became the arena where this struggle took center stage. Major League baseball is a sport unlike any other. For much of [the past] century baseball could almost be considered a national religion. It is no accident that “tradition” is so highly prized by the “Lords of Baseball.” Nor that the singing of the national anthem has become such a prominent part of starting a game. Baseball is, after all, the “national pastime.” U.S. presidents traditionally throw out the first ball. Had Jackie Robinson integrated professional football or basketball, he’d be a forgotten figure today. But breaking the color barrier in baseball would present a new image of the U.S. to the world. However, the more far-seeing leaders of U.S. imperialism found that most of their class was so racist they had no inclination to support integration at any level. Major League owners wouldn’t budge The owners of the 16 Major League franchises were no different. These owners were, if anything, more right-wing than most of their fellow businessmen. They treated their teams as private plantations where they amused themselves with their “toys.” They got some notoriety by getting their names in the newspapers and/or used the teams to advertise their “real” businesses. There was no way these reactionary owners, as a group, would voluntarily allow a Black player into the Major Leagues. A few team owners might have been willing to integrate the Major Leagues, but the overwhelming majority were not for it. The Brooklyn Dodgers were the original “America’s Team.” The “Beloved Bums” were second only to the New York Yankees as the richest sports franchise in the world. The team performed in New York City—the very capital of high finance and home to the United Nations. The Dodger’s general manager was none other than Branch Rickey, the most renowned front-office baseball figure of the century. He was considered the most far-sighted baseball leader. For the ruling class, he offered the added bonus of being very religious and anti-communist, as well as parsimonious when it came to paying the players. The Dodgers were in the National League, considered a traditionally weaker league. It was only natural that a far-sighted, practical general manager would see the acquisition of Black players as a means of redressing this weakness and making the team more profitable. Rickey, together with Baseball Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler, planned the coup that got Jackie Robinson into the Major Leagues. Rickey and Chandler used this power to get Robinson into the Major Leagues, over the objections of almost all the other owners. For this “treachery,” Chandler was bounced out as commissioner at the end of his term. Articles copyright 1995-2012 Workers World. Verbatim copying and distribution of this entire article is permitted in any medium without royalty provided this notice is preserved. Workers World, 55 W. 17 St., NY, NY 10011 Email: ww@workers.org Subscribe wwnews-subscribe@workersworld.net Support independent news DONATE