How To Write a Scholarly Reasearch Report

advertisement

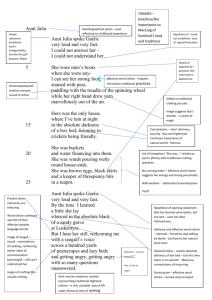

Chapters 1–3 Summary Chapter 1: Quoyle The Shipping News opens by introducing the main character in the novel, Quoyle. The narrator tells that at thirty-six, Quoyle goes off to Newfoundland, home of his ancestors, but then the narration flashes back to provide some background information. Since he was a small child, Quoyle was regarded as a failure by his family, and he grew up ashamed and lonesome. The narrator describes him as a "great damp loaf of a body," his "chief failure, a failure of normal appearance." Not only is Quoyle extraordinarily large and fleshy, but he also has an abnormally large chin, a "freakish shelf jutting" out from his face. After dropping out of college, Quoyle lives in a town called Mockingburg, where he meets a friend, Partridge at the Laundromat. Hungry for friendship, Quoyle begins spending many evenings dining with Partridge and his wife, Mercalia. An excellent cook, Partridge also works at the local newspaper and gets Quoyle a job as a reporter. Quoyle is a terrible writer, but still feels energized and inspired by his job. Partridge is harsh with him at work, but helps him nonetheless, and remains his friend outside the office. Ed Punch, the editor, repeatedly fires and hires Quoyle, and Quoyle finds odd jobs to do in between the newspaper stints. The editor notes that for all Quoyle's faults, he has an uncanny way of inspiring people to talk and tell their stories. Partridge and Mercalia move to California. Mercalia has become the first black woman truck driver in the country, giving up academia in favor of blue-collar work. Quoyle feels lost left in Mockingburg, uncertain of where his life will take him next. Chapter 2: Love Knot Quoyle meets Petal Bear at a meeting he is presumable covering for the paper. Quoyle falls for her erotic provocation immediately, and they begin a love affair that only offered one month of happiness, and six years of suffering. The narrator likens Petal to Genghis Khan, constantly conquering men with sexual encounters. She was attracted to Quoyle for the sex, but finds his form and personality detestable. They marry quickly, and Petal unashamedly spends all her time going after other men. She calls Quoyle from Alabama to make him read her a drink recipe; she brings home a man and has sex with him in the living room within Quoyle's earshot. She gives birth to two daughters, Bunny and Sunshine, who she neither wants or loves. Quoyle suffers deeply, wanting her desperately in spite of her cruelty. Chapter 3: Strangle Knot Quoyle's parents, who belong to the Dignified Exit Society, commit suicide together after both being diagnosed with tumors. His father leaves a message on Quoyle's answering machine, telling him that they have made arrangements for the cremation. Quoyle's brother does not come to the funeral, only concerned with his inheritance. Quoyle's father's sister, Agnis Hamm does not go either, but comes to visit Quoyle to pick up the ashes. Around this time, Petal leaves with another man, taking her daughters with her. Quoyle comes home to the unpaid babysitter, and goes about trying to get his children back. The aunt arrives, and comforts him with tea and kindness. Although Quoyle keeps trying to defend Petal, the aunt understands immediately that Petal is a "bitch in high heels." Eventually, the police find Petal and the man dead from a car accident. The children are found in a child molester's house; presumably, Petal had sold them to him. They have not yet been sexually abused, and are returned to Quoyle. His children gravitate toward his arms. The aunt decides she will stay for a little while, until things get settled again. Analysis The excerpts from the Ashley Book of Knots that precede the chapters introduce a motif that will recur throughout the book. The definition of "quoyle" precedes Quoyle's character, anticipating his personality for the reader. The quoyle (or coil of rope), when made in one layer only, can be used for walking on. Quoyle, as a character, is continually put down, submissive to the cruelty of those around him. This definition also frames the boundaries of Quoyle's character, in effect teaching the reader how he or she should read Quoyle. The reader automatically looks for evidence in the text that Quoyle is a walkedupon character. Indeed, these chapters develop Quoyle's submissive, resigned character, one constantly the object of cruelty. On the first page of the novel, the narrator says that he long learned to "separate his feelings from his life"; in other words, he makes no effort to stave off others' insults and cruel behavior. At the newspaper office, he does not even feel hurt when others bellow names at him, and constantly insult his work. Any other person would be less likely to put up with an editor consistently firing him, but Quoyle endures others' disrespect as if he does not believe he deserves to be treated any better. He cries when he stains all of his laundry; he is not only a failure, but he is also resigned to his status as such. Proulx creates a world that is hyperbolically cruel, almost to the point of comedy. The plethora of hurtful characters creates a sense that the reader has entered an exaggerated world, in which almost without exception, bad news is followed by bad news. Quoyle's father, when not trying to drown him, taught him he was a failure, while his brother offered incessant insults. Petal Bear is so cruel that she borders on caricature. Small details add humor, but only in the context of a dark world. The father leaves a message on Quoyle's answering machine in order to give instructions about his funeral; Sunshine slides in dish soap, covered in chocolate, avoiding a close brush with sexual abuse; Petal sells her kids to a child molester before taking off to Florida with a new man, and then dies on the way. In the context of this world, any neutral circumstance comes as a relief. The idea that Quoyle finds such fulfillment in the mundane jobs of a third-rate newspaperman suggests that a world absent of pain is a good world. The list of world crises at the end of the first chapter, like the cast of hurtful characters, is another example of hyperbole. The terrors of disease, natural disasters, and economic downfall make the stories Quoyle reports— mundane local affairs—seem comforting and even fulfilling. He finds great satisfaction in the idea of entering a world where nothing of any importance happens. In the context of local meetings, he finds order and clarity that a confused, cruel world at large does not offer. By the time the aunt shows up, making tea for Quoyle in his crisis, the reader most likely regards her as a literal saint. The knot itself crops up in the text in myriad forms. In general, the knots that are used as chapter titles symbolize a theme or event within the chapter. The story of the love knot that precedes Chapter Two describes in detail how the tightness of the knot symbolizes the strength of a lover's commitment. Like a sailor at sea with an uninterested sweetheart at home, Quoyle has received numerous signs from Petal that their love is no longer. A "loose" woman in the sexual sense, she resembles the knot in its most loose form. Quoyle, alternatively, holds on to the idea of their marriage so tightly that he is living in perpetual misery. One may liken his emotion to the knot in its tightest form. Even the language in the chapter relates back to the knot; when he meets her, Petal "[throws] loops and crossings" in his stomach, as a cruel lover might tease (suggest the possibility of a tied knot) when in fact she has no interest. The strangle knot of Chapter Three, that holds "a coil" suggests that the events of this chapter will sufficiently strangle Quoyle. Indeed, he breaks down when he finds Petal is dead, and his children have narrowly escaped tragedy. Chapters 4–6 Summary Chapter 4: Cast Away The aunt has convinced Quoyle to move himself and children with her to Newfoundland. After dreaming about Petal in a bread truck with a strange man, Quoyle realizes he needs a change in his life in order to move on. He calls Partridge to see if his old friend has any newspaper connections in Newfoundland, and Partridge, always anxious to help finds him a job. Aunt, Quoyle, Bunny and Sunshine are on the ferry, and when the aunt sees the island, she begins to cry for her old homeland. She feels herself arriving as so many people have arrived to this island throughout history. She thinks of the "malefic spirits" that the harsh conditions here tend to breed. She also remembers her father dying, as the result of the failure of a knot tying a can hook. Chapter 5: A Rolling Hitch The aunt, Quoyle, and children are driving around the island, trying to get to Quoyle's Point, the location of the aunt's old home. The road to Capsize Cove, which is on the way, is old and muddy. Finally, they give up for the night, and decide to sleep the night on the side of the road. Bunny gets angry and tells Quoyle he is dumb, for which the aunt scolds her sharply. The next day, as they head out again, Bunny dreams of blue beads that keep slipping off the string, even though she holds it with both hands. Meanwhile, the road turns to a good gravel and eventually, the group finds a concrete building, all locked up. They stop and have some tea, and the aunt sees the old house through the fog. When they climb up to it, they find it has deteriorated over the years; still, it is filled with memories for the aunt, and she is determined to fix it up. Bunny asks if Petal will come to live with them there, wishing she could wear her mother's blue beads. Alone at the back of the house, Bunny sees a white dog, that gives her a huge fright. When she comes to find Quoyle, he cannot find the animal anywhere. Chapter 6: Between Ships Since Quoyle's job is in Killick-Claw, the location of the house presents a problem for him. The aunt suggests he get a boat, since it would be easier to get to town across the bay, than get up the first part of the road. Since the house is not ready anyway, and the aunt wants to set up her own business (she is an upholstery maker), they decide to rent a room in town for awhile. The aunt makes a list of what needs fixing in the house before they head back up to town. One the way, Quoyle stops for coffee and finds out the concrete structure they found used to be a glove factory. Caught in a snowstorm, the group cannot get back to Killick-Claw. They find the run-down Tickle Motel, where they stay the night. Sunshine wakes up with a nightmare, and the aunt comments that "the Old Hag's got her" referring to Petal. Quoyle feels equally tormented by Petal's ghost. The next day, they lock themselves in the hotel room, and with a dead telephone, finally resort to hanging a rescue sign in the window. Analysis These chapters introduce the novel's Newfoundland setting. As the site of Quoyle's ancestry and the aunt's family, Newfoundland is rich with memories and history. When Quoyle is a young boy, he fantasizes that he had been given to the wrong family, and thinks of a family with a changeling of the Quoyles coming to retrieve him. In a sense, the aunt and the Newfoundland shores are a kind of new family for Quoyle. Quoyle also sees a portrait in Ed Punch's office, who he guesses may be Ed's grandfather, and gets to thinking about ancestry. This kind of preoccupation with familial history anticipates the move to Newfoundland. The three chapters that introduce the new setting also develop the aunt's character. The aunt, having lived in Newfoundland through her childhood and youth, feels a strong sense of home as she returns to the island. The first sight of Newfoundland is told through her eyes, as she thinks of all the peoples who came here, looking for cod and cities of gold, and locates herself among them. She too, the reader finds out in later chapters, is running from an old life, longing for a sense of home, just as Quoyle is. The passage at the end of Chapter Four in which the aunt sees Newfoundland for the first time in fifty years, shows the way that landscape and place is always culturally inscribed. That is, the landscape is not a given that the character acts against, but the landscape is in fact produced by the prejudices and cultural values of the character. The harshness of the Newfoundland landscape is presented through the loving eyes of the aunt, to suggest that this landscape offers strength and character even in the midst of poverty and desperation. Her memories of the hard life are juxtaposed with her tears at seeing the place for the first time again; the reader feels the sense that the island must offer more than harsh conditions in order to inspire her longing for this place. When, at the end of the chapter, she wonders which has changed more, the place or herself, the narrator establishes the idea of the place as a dynamic entity, instead of an unchangeable backdrop. Newfoundland almost becomes like another character in the novel. The aunt's Newfoundland upbringing is evident in her "stouthearted" personality. Indeed, she also gives the reader a sense that someone in this world knows that Quoyle deserves better. At the end of Chapter Four, it crosses her mind to throw Quoyle's father's ashes in the dumpster. She in a way acts out anger and disgust toward this man on behalf of Quoyle (although the reader has the sense that the aunt has her own history of pain with Guy). A similar situation arises when Bunny yells at Quoyle, and tells him he is dumb. The aunt immediately bellows back at her, refusing to allow her to speak with such disrespect. When Petal dies, it is the aunt who thinks to ask about collecting death insurance. As a sixty-five year old woman, she is also determined not only to fix up a totally deteriorated home, but also plans to start her own upholstery business on the island. The dilapidated house seems to symbolizes the stronghold of the family's legacy on Newfoundland, the potential for a new life, and the threat that their new life is ruined before it has begun. The knot that used to hold the broom in place in the house has failed. Bunny's memory of her mother's beads also dramatizes the symbolic significance of knots and ties. Although she holds the string at both ends, the beads keep slipping away. In a symbolic sense, she cannot be tied or bound to her mother any longer. Even as Quoyle is tormented by memories of Petal, this detail suggests that their old life is fading away, and anticipates a brighter future. Chapters 7–9 Summary Chapter 7: The Gammy Bird On the way to his first day of work, Quoyle sees a woman with a child walking along the road. He arrives at The Gammy Bird newspaper office, he meets the staff, a rich cast of local color. They include the likes of Tert Card, the crusty, sarcastic managing editor; Billy Pretty who writes the Home News page; and Nutbeem who plagiarizes foreign news stories. After observing a few newsroom arguments, Quoyle settles in to acquaint himself with the paper, which includes a borage of ads, a hilarious gossip section, and numerous sexual abuse stories. His second day of work, Quoyle meets Jack Buggit, an old fisherman turned newspaper editor. Buggit reels into a long monologue, telling of his old fishing days, and explains that he was supposed to work in the glove factory by Quoyle's house except that they had no leather nor anyone who knew how to make gloves. Buggit then figured that if there had been a newspaper to give him that news, he would have saved a trip. He tells Quoyle that they will get along as long as Quoyle does not try to offer any "journalism ideas" (and basically does not question Buggit's authority). He ends by telling Quoyle that Quoyle will be responsible for the shipping news and car wrecks. Chapter 8: A Slippery Hitch Back in their hotel room, Quoyle dreads the idea of covering car wrecks since it reminds him of Petal's death. The aunt tells him that he must face his life and go through with it. She feels they need to get out of the hotel room, and suggests that Quoyle get a boat, since that would be the easiest way to commute from the family house to the newspaper. Quoyle is paranoid of a boat, being afraid of water in general. At the newspaper, Quoyle finds out that Dennis, the man helping them fix up the family house, is Jack Buggit's son. Jack had a falling out with Dennis after they lost Dennis's brother, Jesson. Jack is out that day, which seems to be the usual routine. Nutbeem is supposed to be covering a fire, but he ends up talking to Billy Pretty and Quoyle about his boat. After a long terrible bike ride, Nutbeem promised himself he would spend the rest of his life on the water. Nutbeem's story gets cut off when he finally goes to the fire. Quoyle is sent to the harbormaster's office to get the shipping news. Chapter 9: The Mooring Hitch Diddy Shovel used to be known for his physical strength, but now his most outstanding characteristic is his deep voice. Quoyle fixates on a painting of a shipwreck, while Diddy Shovel pulls up the notebooks of ship arrivals and departures. He shows Quoyle The Polar Grinder, a boat in the harbor that transports sushi for Japanese trading. Diddy tells Quoyle the story of Jack and Dennis Buggit. Jack has always feared the sea, although he spends all his time fishing. After Jesson died at sea, Dennis, against his father's wishes, signed up to be a carpenter on The Polar Grinder. Diddy then gives a graphic account of a terrible storm in which the ship was caught. He gets interrupted with a phone call before he can tell Quoyle what happened to Dennis. Quoyle goes down to the wharf and buys a boat for only fifty dollars. He also sees the same woman in the slicker again, finding her striking. Back at the newsroom, Billy Pretty and Tert Card take one look at it and deprecate him for buying such a terrible boat. Analysis These chapters introduce a whole new cast of characters in the town of Killick- Claw. Proulx establishes a rich sense of local color through the newsroom characters. Most all the characters at The Gammy Bird are old fisherman. The newspaper is such a peculiar subculture that Quoyle feels like he is in the school playground "watching others play games whose rules he didn't know." The name "The Gammy Bird" is a bit ironic for this paper. The introduction to the chapter suggests that the gammy bird is the name Newfoundlers gave the common eider, which gathers in flocks for "sociable quacking sections." The author tells that the name "gammy" refers to the old habit of shouting the news from one ship to the next, when the ships passed one another. Although one can see how a newspaper might take this name for its symbolic significance, the folks at The Gammy Bird seem to dramatize the literal meaning of "gamming." That is, for any other paper the name would seem clever since "gamming" is a kind of primitive form of news-sharing, but this room engages itself very literally in "sociable quacking sessions." Very literally, these men are old fishermen, exchanging stories with one another. The content of The Gammy Bird develops this idea further. The men who work there seem more interested in their own stories than in news. The paper is filled with advertisements, and the advertisements and the home section are the only parts of the paper that the reader hears about in detail. Both these sections serve to flesh out the Newfoundland setting and people—both are more about gossip and local color than any "newsworthy" information. Proulx again uses listing as a stylistic technique. The list of ads not only tells a great deal about Newfoundland life, but it also suggests that the ads are the most telling part of the paper—at the very least, they offer specific information that is more important to the reader than any other section. The "news" stories fall into little more than two sensationalized categories: car wrecks, or "SA" (sexual abuse) stories. The idea reducing the perversity of sexual abuse to a kind of genre story again reveals Proulx's darkly comic tone. One can hardly believe that any paper prints four sexual abuse stories per issue, but in the world that Proulx fashions, it seems perfectly credible. The quirks and kinks of Proulx's subculture are reminiscent of Mark Twain's penchant for local color. The narrow confines of a regional way of life paradoxically give the writer more license to exaggerate. Like in any fictional work, the author is not asked to create a world that could be factual, but instead a world that the reader will believe. Chapters 10–12 Summary Chapter 10: The Voyage of Nutbeem Quoyle comes home from work one day to find that the aunt's dog, Warren, has died in their hotel room. The aunt pours herself some whiskey and reports that Dennis will be able to fix up their family house to a point of livability within two weeks. All of a sudden, Nutbeem shows up at the door, hoping to finish the story of his boat. They go downstairs to eat at the hotel dining room, and Nutbeem begins his monologue again. He had made a "modified Chinese junk," and set out to sail across the Atlantic. He plans to sail the rest of the way around the world. Nutbeem then finishes Diddy Shovel's story of Jack Buggit and his son Dennis. Dennis was given up for dead when The Polar Grinder was caught in a storm, but Jack went out and found him. Again, Jack demanded that his son never set foot in a boat again, but Dennis went back to sea immediately, and now the father and son do not speak. While Nutbeem is telling his story, the aunt slips away and goes to put Warren's body in the sea. While she is doing so, she is reminded of Irene Warren, an old friend now dead. Chapter 11: A Breastpin of Human Hair The aunt has bought a new truck, and drives it out to the old family house on the point. Alone at the house, she takes her brother Guy's ashes, and dumps them in the outhouse hole. Quoyle, Bunny, and Sunshine meet her there, and begin helping Dennis work on the house. One morning, Quoyle wakes early and walks down a path toward the shore. He sees pieces of knotted grass that Sunshine, and the narrator tells that there were also knots tied in the tips of the tree branches. He finds trash along the pathway, and decides that he will personally care for this small bit of land, make it a beautiful walk down to the sea. Before he heads back to the house, he finds a curious pin in the rocks. It was a whimsical insect made with human hair, and he throws it into the ocean in disgust. Back at the house, Quoyle braves the climb onto the roof, to put down shingles. Bunny climbs up to help him, naively trying to join her father. Quoyle panics, and gets to Bunny just before she attempts to step from ladder to roof, taking her down to solid ground again. Chapter 12: The Stern Wave Quoyle goes out to try his new boat. At first he feels rather confident, but he cannot figure out how to keep from being drenched by a stern wave. Nutbeem later explains to him all the things wrong with the boat that have caused this problem. Dennis suggests starting over completely with a new boat; at the very least, he says, Quoyle should only go out in good weather. At the end of the chapter, Bunny finds a grain of sand, and presents it to the aunt as the tiniest thing in the world. When Sunshine sees it, she accidentally blows it away. Bunny starts to go after her, but the aunt intervenes, explaining that there is plenty of sand for everyone. Analysis Story-telling and story-tellers are ubiquitous in this novel and establish a sense of mythological history connected with Newfoundland. Already, after only a few days in Newfoundland, Quoyle has heard lengthy accounts from Jack Buggit, Diddy Shovel, and Nutbeem. The story within a story is an important stylistic technique that Proulx invokes. The tone and content of Nutbeem's story offer clues into a collective value system. The story of his boat can be seen as just one small chapter in a whole work of oral history. Nutbeem's story, like many others, shows the constant significance of ships and shipping to this people. The story of how he acquiring his sail, for instance—finding a junk sail at Sotheby's auction in good condition for a good price—does not really impress the reader as much, as Nutbeem might hope. Instead, the reader finds it curious that to this man, the junk sale was nothing short than a "miracle." One is not meant to find the stories themselves as engaging as the way they are told, and the sense of place they establish. The reader recalls the moment when Jack Buggit and Billy Pretty see Quoyle's pathetic boat for the first time. The fact of their disappointment is not nearly so interesting as the way their horrified reaction manifests itself in a fit of passionate disparagement. These chapters also help develop Quoyle's and the aunt's characters. Chapter 11 offers an endearing picture of Quoyle as a father, as he enjoys letting his girls help him work. He is kind and encouraging, praising Bunny for her remarkable strength and telling them bedtime stories. This portrait of him is in direct contrast to his own parents, who did not even bother calling one of their sons before committing suicide. Of course the scene at the end of the chapter in which Bunny seems likely to fall off the roof, shows Quoyle as a compassionate and devoted father. Quoyle always feels like he is doing everything "wrong," and in this moment sees his child "on the wrong side of everything." When Quoyle saves her, he not only saves Bunny from the "wrong side" but also corroborates his own "wrongness." This incident anticipates the change that Quoyle undergoes throughout the book. The way that Quoyle decides to care for the path from the house to the shore also shows a small change in his character, and his self image—in the path project, he finds something that he is confident he could undertake. The narrator implies that Warren's passage out to sea looks like the final scene in an old western. This image seems to be a way of rewriting the love motif that the old westerns dramatized. Instead of the cowboy riding off on horseback with the pretty lady, the aunt—a woman who will always miss her woman friend, and not a husband—says goodbye to her only companion, a female dog. This ritual seems to be a way for the aunt to say goodbye to Irene Warren as well as Warren the dog. Not only does this sailing to the setting sun involve an ending instead of a beginning, but it also involves only women, and not a heterosexual couple. The reader should anticipate the possibility that the aunt's affection for Irene Warren may have involved a romantic relationship. The ancestry theme in the novel is further developed in these chapters as well. Quoyle's relationship to his ancestry at this point in the book, is a bit ambivalent. He feels "lukewarm" about fixing up the family house on the point. Omaloor Bay, where Quoyle takes his boat out for the first time, was named after Quoyle's dimwitted ancestors. Sure enough, Omaloor Bay is the site of Quoyle's most uncouth virgin sail. Quoyle's revulsion upon finding the brooch made of human hair (that undoubtedly belonged to a long-dead ancestor) seems to be symbolic of his general attitude regarding his roots. It is perhaps important to note that the tied brooch, the knots in the trees, and Sunshine's knotted grass are all mentioned during Quoyle's walk to the shore. Symbolically, the knots of the dead (the brooch) are connected to the knots in the trees (the knots of the place) and the knots of the next generation (Sunshine). Chapters 10–12 Summary Chapter 10: The Voyage of Nutbeem Quoyle comes home from work one day to find that the aunt's dog, Warren, has died in their hotel room. The aunt pours herself some whiskey and reports that Dennis will be able to fix up their family house to a point of livability within two weeks. All of a sudden, Nutbeem shows up at the door, hoping to finish the story of his boat. They go downstairs to eat at the hotel dining room, and Nutbeem begins his monologue again. He had made a "modified Chinese junk," and set out to sail across the Atlantic. He plans to sail the rest of the way around the world. Nutbeem then finishes Diddy Shovel's story of Jack Buggit and his son Dennis. Dennis was given up for dead when The Polar Grinder was caught in a storm, but Jack went out and found him. Again, Jack demanded that his son never set foot in a boat again, but Dennis went back to sea immediately, and now the father and son do not speak. While Nutbeem is telling his story, the aunt slips away and goes to put Warren's body in the sea. While she is doing so, she is reminded of Irene Warren, an old friend now dead. Chapter 11: A Breastpin of Human Hair The aunt has bought a new truck, and drives it out to the old family house on the point. Alone at the house, she takes her brother Guy's ashes, and dumps them in the outhouse hole. Quoyle, Bunny, and Sunshine meet her there, and begin helping Dennis work on the house. One morning, Quoyle wakes early and walks down a path toward the shore. He sees pieces of knotted grass that Sunshine, and the narrator tells that there were also knots tied in the tips of the tree branches. He finds trash along the pathway, and decides that he will personally care for this small bit of land, make it a beautiful walk down to the sea. Before he heads back to the house, he finds a curious pin in the rocks. It was a whimsical insect made with human hair, and he throws it into the ocean in disgust. Back at the house, Quoyle braves the climb onto the roof, to put down shingles. Bunny climbs up to help him, naively trying to join her father. Quoyle panics, and gets to Bunny just before she attempts to step from ladder to roof, taking her down to solid ground again. Chapter 12: The Stern Wave Quoyle goes out to try his new boat. At first he feels rather confident, but he cannot figure out how to keep from being drenched by a stern wave. Nutbeem later explains to him all the things wrong with the boat that have caused this problem. Dennis suggests starting over completely with a new boat; at the very least, he says, Quoyle should only go out in good weather. At the end of the chapter, Bunny finds a grain of sand, and presents it to the aunt as the tiniest thing in the world. When Sunshine sees it, she accidentally blows it away. Bunny starts to go after her, but the aunt intervenes, explaining that there is plenty of sand for everyone. Analysis Story-telling and story-tellers are ubiquitous in this novel and establish a sense of mythological history connected with Newfoundland. Already, after only a few days in Newfoundland, Quoyle has heard lengthy accounts from Jack Buggit, Diddy Shovel, and Nutbeem. The story within a story is an important stylistic technique that Proulx invokes. The tone and content of Nutbeem's story offer clues into a collective value system. The story of his boat can be seen as just one small chapter in a whole work of oral history. Nutbeem's story, like many others, shows the constant significance of ships and shipping to this people. The story of how he acquiring his sail, for instance—finding a junk sail at Sotheby's auction in good condition for a good price—does not really impress the reader as much, as Nutbeem might hope. Instead, the reader finds it curious that to this man, the junk sale was nothing short than a "miracle." One is not meant to find the stories themselves as engaging as the way they are told, and the sense of place they establish. The reader recalls the moment when Jack Buggit and Billy Pretty see Quoyle's pathetic boat for the first time. The fact of their disappointment is not nearly so interesting as the way their horrified reaction manifests itself in a fit of passionate disparagement. These chapters also help develop Quoyle's and the aunt's characters. Chapter 11 offers an endearing picture of Quoyle as a father, as he enjoys letting his girls help him work. He is kind and encouraging, praising Bunny for her remarkable strength and telling them bedtime stories. This portrait of him is in direct contrast to his own parents, who did not even bother calling one of their sons before committing suicide. Of course the scene at the end of the chapter in which Bunny seems likely to fall off the roof, shows Quoyle as a compassionate and devoted father. Quoyle always feels like he is doing everything "wrong," and in this moment sees his child "on the wrong side of everything." When Quoyle saves her, he not only saves Bunny from the "wrong side" but also corroborates his own "wrongness." This incident anticipates the change that Quoyle undergoes throughout the book. The way that Quoyle decides to care for the path from the house to the shore also shows a small change in his character, and his self image—in the path project, he finds something that he is confident he could undertake. The narrator implies that Warren's passage out to sea looks like the final scene in an old western. This image seems to be a way of rewriting the love motif that the old westerns dramatized. Instead of the cowboy riding off on horseback with the pretty lady, the aunt—a woman who will always miss her woman friend, and not a husband—says goodbye to her only companion, a female dog. This ritual seems to be a way for the aunt to say goodbye to Irene Warren as well as Warren the dog. Not only does this sailing to the setting sun involve an ending instead of a beginning, but it also involves only women, and not a heterosexual couple. The reader should anticipate the possibility that the aunt's affection for Irene Warren may have involved a romantic relationship. The ancestry theme in the novel is further developed in these chapters as well. Quoyle's relationship to his ancestry at this point in the book, is a bit ambivalent. He feels "lukewarm" about fixing up the family house on the point. Omaloor Bay, where Quoyle takes his boat out for the first time, was named after Quoyle's dimwitted ancestors. Sure enough, Omaloor Bay is the site of Quoyle's most uncouth virgin sail. Quoyle's revulsion upon finding the brooch made of human hair (that undoubtedly belonged to a long-dead ancestor) seems to be symbolic of his general attitude regarding his roots. It is perhaps important to note that the tied brooch, the knots in the trees, and Sunshine's knotted grass are all mentioned during Quoyle's walk to the shore. Symbolically, the knots of the dead (the brooch) are connected to the knots in the trees (the knots of the place) and the knots of the next generation (Sunshine). Chapters 13–15 Summary Chapter 13: The Dutch Cringle Diddy Shovel calls up Quoyle to tell him that a leisure boat built for Hitler is in the harbor, and Quoyle should come take a look. Quoyle takes Billy Pretty with him. On the way, they pass the same woman Quoyle has spotted a number of times before. Billy tells him her name is Wavey Prowse, and they give her and her son a ride. At the harbor, Bayonet Melville, the owner of Tough Baby manages to stop arguing with his wife Silver long enough to give them a tour of his boat. He brags of its indestructibility and explains its Dutch origins and design. He is especially proud of the ornate carving. All the while, Silver yells at him to tell the story of Hurricane Bob. According to Bayonet's story, Tough Baby smashed in seventeen boats and twelve beautiful beach houses during the hurricane, without incurring any damage at all. Both the owner and his wife seem to have bruises and have been drinking. Bayonet explains that he and his wife have come to have the yacht upholstered by one Agnis Hamm. Chapter 14: Wavey At the house, the aunt explains to Quoyle that she has set up her yacht upholstery business, having hired two other women to help her, Mavis Bangs and Dawn Budgel. The aunt tells Quoyle that she used to have a "significant other" named Warren, thinking to herself that Quoyle does not need to know it was Irene Warren. The two women had lived on a houseboat together, and the aunt had taken a course in leather upholstery at Irene Warren's suggestion. The aunt went away to take her course, and planned out how she would start her own business. When she returned home, Irene Warren was dying of cancer. As soon as she died, the aunt bought her dog Warren and started the upholstery business. During the aunt's story, Bunny grows extremely frightened after believing she saw a white dog. Quoyle plays with his daughters, helping them build play castle. Quoyle takes a break from work one day and finds Wavey, the tall woman, out walking. He gives her a ride to her son's school, where she often goes at noontime. Both notice the others' gold band on their ring fingers. Quoyle finds himself most enchanted by her tall presence and the way she walks. Chapter 15: The Upholstery Shop Quoyle visits the aunt's upholstery shop and meets the aunt's assistants, one of whom is working on the leather for the Melville's yacht. The aunt and Quoyle go out to Skipper Will's for lunch, and Quoyle asks her about Bunny. He worries that she keeps imagining a white dog, and she has recurring nightmares and a terrible temper. The aunt attributes Bunny's behavior to a traumatic last few months, and tells Quoyle that she just has not yet learned to "disguise [her] differentness." Still, the narrator mentions that Guy had done something—the reader does not yet know what—for the first time when the aunt was Bunny's age; the aunt is not necessarily trustworthy when it comes to evaluating children's emotional stress. Analysis These chapters invoke foreshadowing in order to create suspense and help move the plot forward. The reader should recognize a few ominous clues that crop up aboard the Tough Baby. First of all, the ship was supposedly made for Hitler, a fact that no one seems to be forgetting any time soon. Bayonet and Silver Melville are not only in the midst of a vicious shouting match, but both seem to have conspicuous bruises on their skin, as if they have been physically fighting. Also, both take a kind of sick pleasure in telling the history of the yacht's amazing destructive capabilities. A careful reader will notice the connection between Silver's name, and the fact that Petal Bear is often associated with the color silver. Chapter 14 provides an occasion for the aunt to tell her own history. The aunt, happy to bore Quoyle with the details of the projects she worked on in upholstery school, deliberately leaves out the fact that her "significant other" was a woman. Curiously, this is perhaps the only detail of the aunt's life that we know, but Quoyle does not. The aunt appears only as a businesswoman, an artisan in the upholstery trade, but not as a lover or sexual partner. Indeed, the aunt does not seem to feel at all burdened by the lack of a confession. She very quickly dismisses her sexuality as something Quoyle could not understand, and moves on; Proulx disallows the sex of the aunt's partner to disrupt the story's priorities. There seems to be no personal gain for the aunt in "coming out" as a lesbian, but she instead "comes out" as a businesswoman. Quoyle had no idea until he boarded the Melville's ship that the aunt was such an adept upholsterer. This chapter helps establish the aunt's strong character again. She has lost a loved one, also, but it did not stop her from starting her own upholstery business. Now, relocated to Newfoundland and in her sixties, she has successfully started it again. Wavey's brief appearance in Chapter 14 is curious, considering that the chapter is named for her (and not the aunt). Perhaps this irony draws attention to the way each woman plays a different role in Quoyle's life. As Quoyle begins to be haunted less by Petal, he no longer needs the aunt's strength so desperately; he seems to be opening up a space in his life for a new love-interest. His attraction to Wavey's posture and gait suggests that he sees her for her grace rather than for her sexual potential. There is something ominous about the conversation Quoyle and the aunt have concerning Bunny. The aunt seems to be hiding something, as she looks at Quoyle cautiously, as if she were examining "a new kind of leather she might buy." This simile suggests she may be sizing up his potential, the chances he will continue to dwell on this idea. The aunt goes on to dismiss all of his worries so emphatically that one wonders if the aunt knows information she is not sharing. Indeed, at the end of the chapter, the narrator mentions Guy, Quoyle's father in a threatening way. He apparently did something when the aunt (or perhaps another "she"—the pronoun's referent is unclear) was Bunny's age. The tone and word choice suggests that there may have been an incident of sexual abuse. Chapters 16–18 Summary Chapter 16: Beety's Kitchen Quoyle's daughters stay at Dennis and Beety Buggit's house during the day, and Quoyle loves picking them up, just to spend a little time at the Buggit's house. One typical day, Dennis tells a story about his friend who was attacked while fishing by a terribly strong tentacle. Dennis also talks about how his dad Jack has tried without avail to convince each and every one of his children to stay off the sea. Jack himself spends his days fishing while he tells the newspaper office he is sick. He has a kind of sixth sense about the sea, knew right away that his son Jesson had drowned, and knew where to find Dennis when he was lost at sea. At the end of Quoyle's visit, a man named Skipper Alfred comes to the door, having heard about Bunny's near fall from the roof. Knowing Bunny liked carpentry, he brought her a brass square to help her measure straight lines and cuts. Chapter 17: The Shipping News The chapter opens with Quoyle's article on Tough Baby, the Dutch ship made for Hitler. In the newsroom, Tert Card gives Quoyle a bad time for writing the ship profile instead of car wreck story. The next day, Jack asks to see Quoyle, and Quoyle expects that he will be in trouble for the story. Instead, Jack asks him to keep writing similar pieces; he wants Quoyle to start a shipping news column. Quoyle realizes it is the first time anyone has ever told him he did something right. Chapter 18: Lobster Pie Quoyle finds out that Wavey's son Herry has Down's Syndrome. Wavey has become a local advocate for Down's children, determined to help Herry reach his potential. She asks Quoyle to take her to the library twice a week, so she can check out books to read to Herry. Quoyle feels excited by the thought of seeing Wavey every Tuesday and Friday. Wavey's father lives next door to her and has a garden of wooden sculptures. One day, Wavey invites Quoyle and his girls in for tea, but Bunny has a fit when she sees a wooden white dog, and Quoyle regretfully takes his daughters home instead. Sunshine asks why Herry does not have a father. Quoyle takes his boat down to buy some lobsters. The aunt talks about making lots of fancy dishes with them, but Quoyle is certain she will end up resorting to the simplest idea. She decides on lobster pie, and invites Dawn Budgel, her young assistant, over for dinner. Meanwhile, Bunny is getting aggravated with her latest carpentry project, and yells at Quoyle to give her a ride in the boat. In the boat, she sees another white dog, but Quoyle dismisses her imaginative dog sightings. Dawn comes over, and the aunt tries to prepare a nice, candlelit dinner. Dawn refuses the lobster meat, saying it reminds her of spiders. Bunny, who has always said the same, now tells Dawn that she loves "red spider meat." During the dinner, Quoyle learns that the people who owned the Hitler yacht took off without paying the aunt for the upholstery job. He also realizes that the aunt's furniture that was supposed to be shipped from Long Island still has not arrived. Analysis These chapters show a major turning point for Quoyle's character in the novel. Quoyle's initiative in writing the article on the Tough Baby, the Hitler ship, lands him a new assignment at the Gammy Bird; indeed, his story has encouraged Jack Buggit to include a whole new section in the paper, for which Quoyle will be responsible. Given the paper's quality, the reader may not see this as a valiant accomplishment. For Quoyle, however, it is the first time "he'd done it right." However small the accomplishment, Quoyle's opinion of himself changes with this event. He goes from imagining Jack Buggit's rage (Quoyle imagines the newspaper headline "Reporter Bludgeoned") to feeling totally assured that he has done the right thing. Like a small child, Quoyle responds readily to approval. Since his childhood was void of any kind of praise (and more often condemnation), Quoyle seems to be re-living his childhood in some way, nurturing for the first time a sense of self-confidence and self-respect. His eagerness to praise and engage with his daughters shows his self-awareness about his own childhood. Proulx alludes specifically to a symbolic childhood in Chapter 16 when Quoyle is sitting in Beety's kitchen. Not only does Quoyle get teary watching the scene of happy children (his own and Beety and Dennis's), but Quoyle also imagines Beety and Dennis as his own "secret parents." Beety's house nurtures a sense of safe space for Quoyle. Surrounded by the din of the T.V., warm bread, and plenty of stories, Quoyle feels a sense of refuge and protection. The house setting not only provides a more benign backdrop for Quoyle's story, but it also, according to Quoyle, brings out the best in him. He becomes "more of a father" but he also feels he does not have to hide his own vulnerability. Quoyle's love interest also shows a good deal of growth in his character. He falls for a woman who first of all, wants his company (Wavey asks for him to give her a ride to the library, and invites him to her home), and secondly, loves her son, and enjoys children in general. Quoyle's deliberate attentiveness to his children is contrasted with Petal's deliberate neglect and cruelty. In a way, Petal was a kind of reincarnation of Quoyle's own cruel parents. This new attraction shows that Quoyle is capable of making behavioral changes that will lead to a life of less pain. Quoyle's reaction to Dawn likewise shows a shift in the way he considers romantic love. The aunt seems to be subtly plotting to get Dawn and Quoyle to take an interest in each other. The reader knows from Quoyle's trip to the upholstery shop (Chapter 15) that Dawn is not at all attracted to Quoyle, and is even a bit rude. When Dawn shows up at their door, Quoyle immediately thinks of Petal. Petal is once again associated with the color silver. The association between Petal and Dawn could potentially catapult Quoyle into another masochistic obsession; that is, there seems to be the potential for more love torture, if Quoyle were to fall for Dawn. Thinking of his life with Petal, Quoyle feels "a pang for this poor moth." This metaphor is loaded with meaning. Casting himself as the moth, Quoyle seems to suggest that he was attracted to Petal like a moth is attracted to light; it was an instinctual response that he could not seem to change. Moths are also associated with death. In these terms, the reader may consider that Quoyle, like the moth cannot help being attracted to that which is dead— literally, Petal, and figuratively, their romantic relationship. This thought also shows Quoyle's awareness of his own behavior. The poor moth seems to represent someone else, but has no role in his relationship with Dawn. Indeed, he shows no attraction whatsoever to this woman who dangerously seems to conjure an image of Petal. These chapters also move the plot forward by delineating more of Bunny's encounters with the white dog. At this point, Bunny's fears are a disruption to all of their lives. These incidents create suspense; the reader begins to wonder what is engendering this fear, and whether Bunny is merely experiencing normal childhood insecurities, or if she has somehow inherited an evil from Quoyle's past Chapters 19–21 Summary Chapter 19: Good-bye, Buddy Tert Card sometimes sent everyone out of the newsroom, and one day Billy Pretty, Nutbeem and Quoyle go out for fish and chips. Nutbeem reports having a deluge of sexual abuse stories. The men swap stories, and Billy invites Quoyle out to Gaze Island, a place Quoyle has not yet sent. Billy also explains how Killick-Claw grew into a community, usurping the role that Misky Bay once served. During the war, so much ammunition and cables were dropped underwater near Misky Bay, that no one wants to anchor his boat in the harbor. Quoyle then reads his friends another article he wrote about a man getting electrocuted on board a boat called Buddy. Chapter 20: Gaze Island Billy Pretty and Quoyle go out to Gaze Island. On the way, Billy points out all names of the rocks sticking out of the water. One, called the Komatik-Dog, looks like a sled dog and is located right at the end of Quoyle's point. The legend was that the dog would wait for a wreck, and eat the drowning people. Billy tells Quoyle stories on the way, too. First, he says that Quoyle's only other living relative Nolan lives around there and wants the family house. Billy also tells Quoyle that Omaloor Bay is named after the loony, dim-witted, and murderous Quoyles. Billy explains to Quoyle how Quoyle's ancestors dragged the green house onto the Point over the ice a hundred years before. Billy Pretty grew up on Gaze Island, and is actually Jack Buggit's second cousin. He explains that the Islanders were known for their knowledge of fishing and volcanoes. Inhabited by only five families, they were an incestuous group. Now, the island is deserted. Billy and Quoyle go ashore, and Billy finds his father's tombstone and repaints it. Quoyle is reminded of his father , who loved fruits. Quoyle thinks he should have been a farmer. Billy, too had a father who should have been a farmer. He was in an orphanage in England, and was sent over to work on a farm in Canada. When the ship got in a wreck, a few boys, including Billy's father, were found by the people on Gaze Island. The Pretty's adopted Billy, hiding him from the people who came to take him on to Canada. It was a good thing, since Billy's father received many miserable letters from his friends who made it to Canada, detailing abusive working conditions on the farms. Billy's father eventually made sure that all of Gaze Island could read and write. Billy tells Quoyle that his father used to say that every man had four women in his heart: the "Maid in the Meadow," "Demon Lover," "Stouthearted Woman," and the "Tall and Quiet Woman." Billy himself never married due to a "personal affliction" which he tried to keep secret. Before they leave, Billy shows Quoyle another cemetery where all of Quoyle's ancestors — pirates and plunderers—are buried. He shows Quoyle a bed of flat rocks where the green house once stood before the Quoyles hauled it to Quoyle Point. They were run out on account of their refusal to attend Pentecostal services. Chapter 21: Poetic Navigation The fog is coming in as Quoyle and Billy head back. They find an expensive- looking suitcase on one of the rocks, and they begin to smell something rotten. Billy is a good navigator, recognizing his route by the rocks. He decides that they will pull into Desperate Cove to wait for the fog to lift. When the get ashore, they grab a meal before Quoyle breaks the lock on the suitcase. Inside is the head of Bayonet Melville. Analysis Chapter 19 again shows Quoyle interacting and living his life within the confines of a safe structure or place. As the newsroom men sit and swap stories, it is obvious that Quoyle is an integral figure in their community. Billy Pretty invites him on a day trip, and the friends willingly listen while Quoyle proudly reads his news story. Having the inside scoop on ships and boats seems to help Quoyle establish himself among his peers. (Billy's and Nutbeem's reactions to the story are telling about their different characters. Billy sensitively calls the story a "shame," while Nutbeem in a startlingly funny way, exclaims that Jack will like it for the "blood, boats, and blowups.") Chapter 20 further develops the theme of ancestry. We learn that Jack Buggit called up Quoyle's references before hiring him to make sure Quoyle was not a murderer. Ironically, Buggit knew that Quoyle was associated with murderers before Quoyle did. Quoyle continues to learn from the locals in Killick-Claw about his own family. This idea points to the importance of place and setting in this novel. Quoyle's personal journey in understanding himself and his family is in a way created by the setting. That is, Quoyle did not really know all he still had to learn about his history until he arrived in Newfoundland and started hearing remarks here and there about his own ancestry. The scene at Gaze Island dramatizes this connection between Quoyle's conflict and setting. Going to the site of Billy Pretty's father's grave—and the site of his ancestors' home—conjures up images of Quoyle's father and demands that Quoyle revisit painful memories once again. The images of Quoyle's father again suggest the quiet violence that characterized Quoyle's childhood; the memory of the beating Quoyle unfairly received for stealing his brother's blueberries is a good example. Seeing the grave of Billy Pretty's father symbolically reopens Quoyle's father's grave. Although Gaze Island is named for its high lookout, we should recognize the symbolic meaning the name carries. The island forces Quoyle to "gaze" into his family's history, and into his own traumatic past. The image of a mirror in this chapter further affirms the symbolic significance of "Gaze" Island: when seeing his ancestors' cemetery for the first time, Quoyle's head jerks back "like a snake surprised by a mirror." In this scenario, the mirror is the cemetery—literally markers of Quoyle's family history. This simile also casts Quoyle as a snake, which calls attention to the malicious wildness that is associated with the Quoyle family. The excerpt from The Ashley Book of Knots that precedes Chapter 20 could be read as an allusion to Quoyle's relationship with his family. His ancestors were a band of pirates, and he, like the pirates' prisoner, is still somehow held in their grip. The excerpt presents a riddle: how do the prisoners free themselves from the pirates? This riddle represents Quoyle's same dilemma. The knots that tie the prisoners' boat to the pirate ship symbolize the way that Quoyle is tied to his past. He must find a way to live a life without pain (free himself) despite his cruel and unusual ancestry. The story of the Quoyle's house adds another tale to the vast annals of myth and folk history on Newfoundland. We should appreciate the irony that the Quoyles were ultimately driven out because of their disinterest in joining the Pentecostal Church. This detail reaffirms the quirky characteristics of Newfoundland folk; again, we feel pulled out of his or her reality, and thrust into a place in which essentially murderers are tolerated until they refuse to put on their church shoes. The novel requires that one look at the "truth" of oral literature. One might question the validity of pulling an entire house on an iceberg like a sled, for instance, but the novel values local legends as reflections of a culture and a people. These chapters also help develop Billy Pretty's character. Billy grows as a sensitive character in his diligence about his father's grave, and his kind remembrances of the old man. He also seems aware that Quoyle is discovering his own past, and concedes that many people were plunderers in the old days on Gaze Island, not just the Quoyles. The name "Pretty" also becomes more significant in these chapters, as Billy shows himself to be appreciative of aesthetic values. He carefully decorates his father's grave, and even his descriptions of the rocks show his capacity to see the creativity in their names. His "poetic navigation"— navigation based on a few rhyming couplets—implies that navigating is perhaps as much an art as a science. Billy uses his skills to maneuver in whatever safe path he can figure given the conditions. Finally, the suitcase carrying Bayonet's head refers to the "Dutch cringle" that titles Chapter 13. The suitcase has a rope handle that could well be tied in a cringle knot and of course, it comes from the Dutch ship. At this point, one can guess that Silver, Bayonet's wife, is probably responsible for his decapitation, just from the nature of their belligerent relationship. We recall that Petal is connected with silver throughout the book; the two women's capacity to cause violent suffering is parallel. It is also important to note that Billy teases Quoyle for acting like a "wracker"—like his ancestors—when he pulls the suitcase off the rock, and claims it for himself.