Anna`s Blizzard by Alison Hart

advertisement

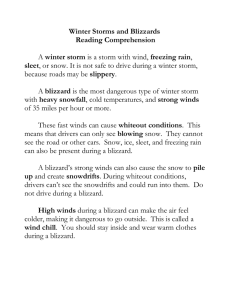

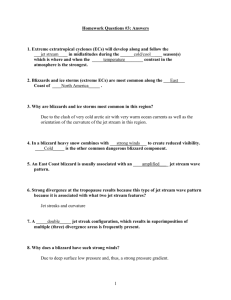

Education Guide History The VOICES of the pioneers who witnessed the blizzard of 1888 are strong and powerful. The history kiosk will help us share the stories of inspiration that make history come alive. We will take a look at the events of that destructive day. Just as the storm took people off-guard, history proves that weather is not as predictable as we might think. Very few Native Americans died during the storm. How did they know the blizzard was about to hit? A fun look at weather folklore that has been passed on through generations will help to balance the heroic and heartfelt stories we hear from the Schoolchildren’s Blizzard. Lesson 1 - Folklore The Native Americans watch not only the skies but paid attention to all nature to help them predict what might happen each season. Throughout history and still today, people try to understand, predict and control weather. Before modern day methods of predicting the weather, other methods were used. The Babylonians predicted weather from cloud patterns in 650 B.C. Aristotle described weather patterns in Meteorologica in 340 B.C. Native Americans tried to control or influence the weather with prayers, incantations, smoking or burning tobacco, using charms or dancing. Most methods of forecasting were based on observation (eyes and senses) and experiences with observing patterns (”If ___ happens, then ___ will happen”). These are not always reliable or true. Farmers, shepherds, sailors and hunters (people whose lives depended on the weather) relied on folklore to predict the weather. Farmers and shepherds watched the animals, clouds and the color of the sky. Sailors observed the wind and the motion of the waves. Hunters observed insects and animal behavior. Folklore was often made into rhymes to make them more memorable as they were passed on over generations. Discuss these folktales and proverbs with your class. Use the internet and science books to see if you can find out the reasoning behind some of these weather related predictions. “The higher the clouds, the better the weather.” “When ants travel in a straight line, expect rain; when they scatter, expect fair weather.” “Sea gull, sea gull, sit on the sand; It’s a sign of a rain when you are at hand.” “Flies bite more often before the rain.” “When squirrels lay in a big store of nuts, look for a hard winter.” “When leaves show their backs, it will rain.” “Bees will swarm before a storm.” “Red sky at night, sailor’s delight; red sky in morning, sailors take warning.” “If spring comes in like a lion, it will go out like a lamb.” “A ring around the sun or moon means rain or snow coming soon.” “Thirty days has September, April, June and November From January up to May The rain it raineth every day All the rest have thirty-one Without a blessed gleam of sun And if any of them have two-and-thirty They’d be just as wet and twice as dirty.” Lesson 2 - Timeline The history kiosk contains a clock that recalls the day of the blizzard. It is a reminder that a warm, calm morning can turn quickly and catch people unprepared for the storm ahead. Discuss the description of the day’s events below and then have children create their own timeline. Ask them if they can recall a life changing event and have them recreate what happened as the day progressed. These can then be written or told through storytelling. January 12, 1888 U.S. Midwest Approximately 235 people lost their lives. (This was a large amount in comparison to the amount of people living in the Midwest at the time of the blizzard.) Was a warm day that quickly turned into a storm Since it came without warning, the amount of devastation was greatly increased (People where not prepared) – Talk about today’s technology that is a help to warn communities of approaching storms. Went from 70 F to -10 F (-40 F in some places) in a few hours Lasted for only a few hours from the afternoon until early evening (3 – 4 feet of snow in that amount of time) Was hard to get around for at least 3 days after the storm was over – compare today’s means of transportation and communication (snow plows, salt trucks, paved roads, rescue vehicles, phones, radio, television, etc.) Is called the schoolchildren’s blizzard because in many places, children were trapped in their schoolhouses (in many cases they had to stay overnight) Most of the schoolhouses were one-room with wood or coal burning stoves. Resulted in the loss of life and the loss of property, travel was severely impeded in the following days (prohibited people from getting home or help) The wind was so loud and strong that people who were only 6 feet away from each other could not hear one another talk. The snow was so heavy that people who were only 4 ft. away from each other could not see each other. Science On January 12, 1888, the storm known as “The Schoolchildren’s Blizzard” caught everyone by surprise. What was happening that day to cause the skies to fill so suddenly with a wall of snow? The science kiosk will examine the phenomena of weather, how weather is predicted today, and what was happening in the earth’s atmosphere to produce the blizzard, which so suddenly struck the Midwest that fateful day. When the Schoolchildren’s Blizzard hit the Midwest it was difficult for people to communicate. We know that today communication is crucial to saving lives. The modern age of forecasting began with advancements in communication systems (telegraphs, radio, telephone, radar, satellite). As communication systems were invented, better weather prediction systems made it possible to relay information as it occurred. The ability to transport information in real time (at the current moment) helped to improve communication of current data in multiple locations as well as improving communication with the public (warning capabilities). There are a few methods that meteorologists use to come with their “best guess” to predict the weather. It is a “best guess” because, even with modern day technological advancements, the atmosphere is still a chaotic phenomena and not completely predictable. To help predict the weather, you need to look at three things: temperature, precipitation and cloud coverage. Weather generally travels from west to east in the United States. Meteorologists forecast weather by plotting observations on weather maps every hour to locate warm/cold fronts and areas of high and low pressure to tell where “weather systems” are moving and how fast they are moving. Modern forecasting involves looking at both the ground and space by using computers and weather satellites (which orbit the earth and take photos of clouds from space). Meteorologists use a combination of different methods to make forecasts: Persistence Forecasting – look at what the weather is doing at the moment to predict what will happen plot observations every hour observe weather with tools - thermometer (measure temperature) - barometer (measure air pressure) - rain gauge (measure precipitation) - anemometer (measure wind speed) - radiosonde (attached to a balloon to measure high atmosphere weather) - satellite (orbits earth and takes pictures of clouds from space to see where and how fast the clouds are moving) - - radar (shoots a radio signal into a cloud to show where precipitation is falling and how much is occurring) (spots severe storms and how fast they are moving) ears and eyes ( observe clouds and precipitation) Synoptic Forecasting – forecast method based on analysis of set and/or series of synoptic charts Statistical Forecasting – looking at previous statistics of what weather is usually like during a certain time of the year Computer Forecasting – plug observation into computers (the computers can compute complicated equations) make computer “models” to get forecasts different computers give different results; therefore, humane involvement is necessary. Lesson 1 - Thermometer You can usually tell what the temperature is like by just walking outside. You may say, “It is so cold today.” or “I can’t believe how hot it is.” A thermometer tells us exactly how hot or cold it is. The temperature goes up and down in steps called degrees. Thermometers measure temperatures in two different scales Fahrenheit and Celsius. On the Fahrenheit scale water boils at 212 degrees and freezes at 32 degrees. On the Celsius scale water boils at 100 degrees and freezes at 0 degrees. A very hot day might be 40 degrees Celsius or 100 degrees Fahrenheit. A very cold day might be -5 degrees Celsius or 20 degrees Fahrenheit. Using a Thermometer Supplies: indoor/outdoor thermometer a stop watch or clock 1. Hold the thermometer so that the bulb is at the bottom, but do not hold the thermometer by the bulb. 2. Turn the thermometer from side to side so that your eyes can find the red line. 3. Find the top of the red line. What is the number next to the mark at the top of the red line? That would be the temperature. 4. Take different readings in your classroom. You should wait about 5 minutes each time you measure. You can use a stop watch or clock to help you. 5. Try these measurements. Keep track on a piece of paper and then compare with other students in the classroom. What is the temperature at you desk? What is the temperature at your teacher’s desk? What is the temperature that the window? What is the temperature at the door? Lesson 2 – Clouds Meteorologists study the skies to observe cloud cover. Some clouds are light, white and fluffy. This means that they contain very little water and the sun can shine through them. Other clouds are dark. These clouds contain a great deal of water so sunlight can not shine through. Dark clouds usually mean rain is on the way. There are three main cloud types. Cumulus clouds are the puffy clouds that look like puffs of cotton. Cumulus clouds that do not get very tall are indicators of fair weather. If they do grow tall, they can turn into thunderstorms. Stratus clouds look like flat sheets of clouds. These clouds can mean an overcast day or steady rain. They may stay in one place for several days. Cirrus clouds are high feathery clouds. They are up so high they are actually made up of ice particles. They are indicators of fair weather when they are scattered in a clear blue sky. Nimbus is another word associated with clouds. Adding "nimbus" means precipitation is falling from the cloud. Cumulonimbus clouds are the "thunderheads" that can be seen on a warm summer day and can bring strong winds, hail, and rain. Nimbostratus clouds will bring a long steady rain. Make a Cloud Supplies: Large empty glass jar Metal strainer Hot water Ice cubes 1. Fill the jar with hot water and leave it there for two minutes. Then pour out most of the water, leaving just an inch or two at the bottom of the jar. 2. Put the strainer over the mouth of the jar. 3. Fill the strainer with ice cubes. 4. Watch what happens. Some of the hot water at the bottom of the jar turned into hot water vapor. The vapor rose and bumped into the cold air coming off the ice cubes. When the water vapor condenses it forms a cloud. Hot air raises and contains a great amount of water vapor. As the air rises higher in the sky, it cools down. Soon the cold air can’t hold all the water vapor and it starts turning into a cloud. Lesson 3 – Fronts A front is a transition zone between two different air masses with different temperatures and humidity levels. Fronts cause the weather in FRONT of them to change. Warm Front: An area in which warm, moist air from tropical areas is replacing colder, dryer air from the poles. A warm front is drawn on a weather map as a solid red line with half circles indicating the direction the front is moving. Warm fronts are generally about half the speed of cold air masses. Cold Fronts: An area in which cold, dry air from the poles is replacing warm, moist tropical air. A cold front is drawn on a weather map as a solid blue line with triangles indicating the direction the front is moving. Cold fronts typically move twice as fast as warm fronts. Weather Math Meteorologists calculate the movement of a weather front by using a very simple formula: Multiply the speed of the warm/cold front (mph – miles per hour) by the number of hours in a day (24). ___mph x 24 hrs = ___miles traveled By using this formula see if you can calculate the movement of the following fronts. 1. You have a cold front moving in an easterly direction at 25 mph. How far will it travel in one day? 2. You have a warm front moving up from the south at 15 mph. How far will it travel in one day? 3. You have a cold front moving from the Midwest to the northeast at 40 mph. How far will it travel in two days? 4. You have a warm front in California moving toward Nebraska at 30 mph. How far will it travel three days? Lesson 4 – Beaufort Scale Wind conditions are critical in the development of a blizzard. Wind is AIR moving over the earth’s surface. Most winds are caused by either topography or the movement of high and low pressure systems or fronts. A Gentle Wind occurs when two fronts come together that are not very different in humidity and temperature. A High Wind occurs when fronts of very different temperature and humidity come together. Wind blows because it has weight. Cold air weighs more than warm air so when the sun warms the air, it expands, get lighter and rises. Cooler heavier air blows to where the warmer lighter air was, so wind usually blows from areas of high pressure to areas of low pressure. The Beaufort Scale was named after Sir Francis Beaufort (1774-1857). He was an English admiral and naval hydrographer. The scale estimates and describes wind speed. The wind speed is based on a visual estimation of the wind’s effects, ranging from force 0 (calm) to force 12 (hurricane). Beaufort Wind Scale Developed in 1805 by Sir Francis Beaufort of England Appearance of Wind Effects Wind WMO Force (Knots) Classification On the Water On Land Less Sea surface smooth and Calm, smoke rises Calm 0 than 1 mirror-like vertically Smoke drift indicates wind direction, still wind vanes 1 1-3 Light Air Scaly ripples, no foam crests 2 4-6 Light Breeze Wind felt on face, leaves Small wavelets, crests glassy, rustle, vanes begin to no breaking move 3 7-10 Large wavelets, crests begin Gentle Breeze to break, scattered whitecaps 4 11-16 Moderate Breeze Dust, leaves, and loose Small waves 1-4 ft. becoming paper lifted, small tree longer, numerous whitecaps branches move 5 17-21 Fresh Breeze Moderate waves 4-8 ft taking Small trees in leaf begin Leaves and small twigs constantly moving, light flags extended longer form, many whitecaps, to sway some spray 6 22-27 Larger waves 8-13 ft, Strong Breeze whitecaps common, more spray 7 28-33 Near Gale Sea heaps up, waves 13-20 ft, Whole trees moving, white foam streaks off resistance felt walking breakers against wind Gale Moderately high (13-20 ft) waves of greater length, edges Whole trees in motion, of crests begin to break into resistance felt walking spindrift, foam blown in against wind streaks Strong Gale High waves (20 ft), sea begins Slight structural damage to roll, dense streaks of foam, occurs, slate blows off spray may reduce visibility roofs 48-55 Storm Very high waves (20-30 ft) with overhanging crests, sea white with densely blown foam, heavy rolling, lowered visibility 56-63 Exceptionally high (30-45 ft) Violent Storm waves, foam patches cover sea, visibility more reduced 34-40 8 41-47 9 10 11 12 64+ Hurricane Larger tree branches moving, whistling in wires Seldom experienced on land, trees broken or uprooted, "considerable structural damage" Air filled with foam, waves over 45 ft, sea completely white with driving spray, visibility greatly reduced In the exhibit students can see the visual impact of the Beaufort Scale by viewing a force 0 day and a force 12 day through a zoetrope. Have students pick one of the force ratings on the Beaufort Scale and see if they can visually replicate it by making a flip book. Supplies: scissors white paper cut into fourths (students will need about 36 sheets) stapler pencil or markers 1. Choose one of the force ratings on the Beaufort Scale 2. On the first frame draw a picture of a place (could be your backyard, house, your school, etc.) 3. Imagine what the wind would do 4. Keep changing the picture on each frame to show what you think might happen with the force you have chosen 5. Remember that you will make slight changes to each frame until you fill up every page. 6. Put the frame in order and staple three to four staples across the top of your flip book 7. Hold the book in your hand and flip the pages. The pictures should move like the zoetrope in the exhibit. Geography The Schoolchildren’s Blizzard took place in the Great Plains of the United States. The Great Plains are located from the Rockies to the Mississippi River west to east and from Canada to Texas north to South. The states that were affected by the storm are: North and South Dakota, Montana, Minnesota, Nebraska, Kansas, and Texas. Many of these states were just territories during the time of the blizzard. During the Schoolchildren’s Blizzard, the snow and wind were so strong that a person could not see two feet in front of them and could not hear people 6 ft in front of them. This snow blindness led to disorientation when people tried to get to a safe shelter. Many people lost their lives or suffered injuries because they could not find their way. People tried many different techniques to find their way. They tied themselves to each other to stay together. This technique was used by a one room school teacher named Minnie Mae Freeman from Ord, Nebraska. She single-handedly saved her schoolhouse full of children from the storm by tying them all together to find their way to safety. People tied ropes to a building. As they went out to search for others, they let the rope act as a guide to get back. Some remembered the layout of the land; a row of sunflower stocks, a drainage ditch or a fence. These landmarks help guide people who were in a barn or shed when the storm hit. Lesson 1 – Natural Disasters A natural disaster can occur anywhere in the world. Most are caused by weather. Discuss the list below. Have children join together in teams, pick a disaster, and find more detailed information about where and how they occur. Take time to pin-point them on a globe or world map. Blizzards, Hailstorms and Ice Storms Tornadoes Hurricanes, Tropical Storms, Typhoons Earthquakes Drought Wild Fire Tsunami Volcano Eruption Landslides Avalanche Lesson 2 – Be Prepared It is important for every family to have a disaster plan. Discuss the information below and then have each student put together a disaster plan with their family. You might want to also discuss the disaster plan for your school. – Gather Information Contact local weather agencies or the American Red Cross and gather information on possible disasters in your area and how you should respond. – – Meet with your Family and Develop a Plan Discuss the information you have gathered. Pick two places to meet; a spot outside your home for an emergency, such as a fire, and a place away from your neighborhood in case you can’t return home. Choose an out-of-state friend or family member as your “family check-in contact” for everyone to call if the family gets separated. – Implement Your Plan - Post emergency numbers by the phone. Make sure each family member has your “family check-in contact” programmed into their cell phones. - Know how to turn off utilities (water & gas) - Make sure safety items are in your home. 1. fire extinguisher 2. smoke detector - Create two disaster supply kits (one for home and a smaller one for the car) 1. a 3-day supply of water and non-perishable food (canned with can opener) 2. blankets 3. first-aid kit, special medications, radio, flashlight and extra batteries Lesson 3 – Find Your Way People used many landmarks to help them find their way during the storm. Take time to set up your classroom in a different way. Allow everyone a few minutes to study the layout. Blindfold a few students to see if they can remember how to get from the front of the classroom to the door. Remember that during the blizzard they could not hear or see anything, so no prompting from other students. Discuss with the class to see if they remember landmarks around their home that would help them find their way back to the house should a storm hit. Art The Schoolchildren’s Blizzard is based on the book of poetry The Blizzard Voices by Ted Koozer, so its very creation was based on a work of art. When reading the book we realized that the pioneers of that time were surrounded by art that grew out of necessity. Quilts were blankets designed to protect against the cold weather, but developed into a form of artistry and storytelling. Additionally, many pioneers made comments about the artistry of the snow itself. Each snowflake is a unique creation. Art is a form of expression that is conveying the beauty, emotion and personality of even the most devastating situations. Lesson 1 – Snowflakes What are snowflakes? Snowflakes are made up of ice crystals. Snow crystals form when water vapors condense directly into ice clouds. Patterns emerge as the crystals grow. How are snowflakes formed? Water vapor (the gas from water) in the atmosphere cools so much that it changes from a gas to a liquid or solid (it condenses). Snow starts as water vapor in the air (evaporated from oceans, lakes, etc.). The water vapor condenses into droplets. The combination of droplets forms a cloud. The cloud gets cooler and droplets start to freeze around nucleators (tiny bits of “dirt, bacteria and other material floating around in the atmosphere” that attract water molecules helping them to come together). Frozen droplets become small particles of ice crystals and these crystals from snowflakes. The snowflake gets heavier and they fall to the ground. Make Ice Crystals Supplies: Crushed Ice Salt Glass Petri Dishes or Small Clear Glass Dish Wooden Craft Sticks Overhead Projector Kool-Aid Drink Plastic trays Plastic bowls Glass Container for Crushed Ice Plastic sheet to cover work area Individual Flash Lights What’s Happening: Freezing occurs when water is cooled down; the molecules move more slowly, causing the water molecules to come together and begin the formation of an ice crystal. Usually this process takes a long period of time because the cooling is done slowly. This process can be speeded up by rapid cooling to temperatures just below the freezing point. This process is known as super cooling. When ice crystals form from a super cooled water solution, the crystals form very rapidly. Under these conditions the ice crystals can actually be seen to grow. Experiment: Using a Kool-Aid drink, place some orange Kool-Aid into a petri dish. Prepare a bowl of ice and salt. Mix the crushed ice with salt until the temperature is below the freezing point. If desired, test the ice/salt mixture with a thermometer to make sure that the temperature is below the freezing point. Place the petri dish on the ice/salt mixture; watch patiently for 3-5 minutes. Poke the liquid slightly a few times with a wooden craft stick during this waiting period. Then, the ice CRYSTAL will start forming! Amazingly, it continues to grow very quickly and you can observe this process very vividly. The growing will last about 1 minute. Student should hold a flashlight under the petri dish to observe the crystal structure. A follow-up to this experiment is to do the same experiment on an overhead projector. Light shining through the glass petri dish from the overhead projector or a flashlight allows the close visibility of the crystal formation and structure. Lesson 2 – Making Paper Snowflakes No two snowflakes are alike. Wilson Bentley was a farmer who lived in Jericho, Vermont. The snowfall is around 120 annually. Wilson was fascinated by snowflakes and decided that he would like to photograph as many as he could. No one had ever photographed a snowflake. He adapted a microscope to a Bellows Camera. In 1885 (three years before the Schoolchildren’s Blizzard) be successfully photographed the first snowflake. He is said to be the pioneer of photomicrography (taking photographs of microscopic objects). His work has earned him the name “The Snowflake Man”. You can see some of Wilson Bentley’s original photographs by looking through the Bellows camera in the Art Kiosk of The Schoolchildren’s Blizzard exhibit. Follow the directions below to make a beautiful, one-of-a-kind, snowflake. Hang them around the classroom. Challenge children to make unusual designs using their name or drawing a picture on the folded paper. Reference Books: Snowflake Bentley by Jacqueline Briggs; Snowflakes by Marion Nichols Lesson 3 – Art Quilts Quilts are decorative blankets designed for warmth. The pioneers used them during the Schoolchildren’s Blizzard to keep them warm, but hey also represented great craftsmanship and each one had a story. Quilting is a method of sewing two layers of insulating batting in between two layers of cloth. One side of the quilt contains a pattern or pictures that often tell a story. The cloth may be leftovers from children or adult clothing that was worn for a special event. A quilt was often given as a gift for the birth of a child or a marriage. Make a Classroom Quilt Supplies: White Cotton Squares (These can be purchased already sewn with buttons for fastening together from Discount School Supply or Oriental Trading Company) Fabric Markers Hand out a fabric square to each student. They may need to share markers so they can work in groups. Have them draw a pictures of one their favorite school activities or school events. They could also each draw a picture of their family and it could be a family community quilt. After squares are finished allow each child to tell their story before it is added to the quilt. Literacy Anna’s Blizzard by Alison Hart Twelve-year old Anna would rather tend sheep on her Nebraska farm then go to school where she struggles with all her lessons. But Anna’s quick thinking and bravery save her classmates and teacher’s lives when a blizzard destroys their school house and they must make their way to the closest neighbor’s farm in a total white-out. Activities – 1) The Great Blizzard of 1888 happened so long ago that we think we would never be surprised by a storm of that size today. Learn about today’s weather predictions by inviting a local weatherman or meteorologist to your class to discuss how weather is tracked today. Learn about long range forecasting accuracy, and changes that can indicate a storm is approaching an area. 2) Watch a storm develop on radar for a week by tracking its progress every day from a weather web site. Did the storm hit as predicted? What preventive measures were thought of in advance of the storm? 3) Anna ate cornmeal mush for breakfast. Have your class prepare a pioneer breakfast that includes this staple. You can usually find the recipe on the back of any cornmeal box. How has this morning meal changed since the 1880’s? Why did pioneer families eat more starchy foods then we do now? 4) Plan an afternoon of classic children’s games that includes “Button, Button, Who’s got the Button?” and marbles. Have the class compare and contrast their favorite games of today to those of yesteryear. Is anyone willing to trade their video games even for a day with those that entertained children of the past? 5) Learn all about one room school houses, and research how many still exist in Nebraska, and in the United States. Ask the class if they believe they get a better education than pioneer children and why. Chart the pros and cons and lead a classroom discussion on this topic. 6) Introduce classic books to your class that children were reading in the 1880’s, like Louisa May Alcott’s books and those by Mark Twain. Read a chapter or excerpt and ask the class if they believe they would enjoy these titles today. Other Books by the author: Fires of Jubilee, Aladdin Paperbacks, c2003 Gabriel’s Horses (Racing to Freedom Series), Peachtree Publishing, c2007 Gabriel’s Journey (Racing to Freedom Series), Peachtree Publishing, c2007 Gabriel’s Triumph (Racing to Freedom Series), Peachtree Publishing, c2008 Rescue: A Police Story, Aladdin Paperbacks, c2002 Return of the Gypsy Witch, Aladdin Paperbacks, c2003 Shadow Horse, Random House, c1999 Alison Hart is also the author of the Riding Academy series books. Companion books: Bird, E. J., The Blizzard of 1896, Carolrhoda Books, c1990 Gray, Dianne E., Together Apart, Houghton Mifflin, c2002 Hopkinson, Deborah, Cabin in the Snow, Aladdin paperbacks, c2002 Hutchens, Paul, Lost in the Blizzard, Moody Press, c1998 Kehret, Peg, The Blizzard Disaster, Pocket Books, c1998 Murphy, Jim, Blizzard: the storm that changed America, Scholastic Press, c2000 Naylor, Phyllis Reynolds, Blizzard’s Wake, Atheneum books, c2002 Wilder, Laura Ingalls, The Long Winter, HarperCollins, c1953 Other Books to Consider: The Blizzard Voices by Ted Kooser What Will the Weather Be? by Lynda Dewitt; Illustrated by Carolyn Croll The Blizzard by Betty Ren Wright; Illustrated by Ronald Himler Turbulent Planet: White-Out Blizzards by Claire Watts The Seasons: Winter by Nuria Roca; Illustrated by Rosa Maria Curto The Snowflake Winter’s Secret Beauty by Kenneth Libbrecht; Photography by Patricia Rasmussen Snowflake Bentley by Jaqueline Briggs Martin; Illustrated by Mary Azarian Internet Connections: Websites for Alison Hart: Author Booking Services Site: http://childrenslit.com/bookingservice/hart-alison.html Children’s Book Guild of Washington, D.C. http://www.childrensbookguild.org/hart.html Weather Websites about Blizzards: National Snow and Ice Data Center: Check out these photographs http://nsidc.org/snow/gallery/ Blizzard Lesson Plans from Scholastic: http://content.scholastic.com/browse/collateral.jsp?id=1069 Frontier Prairie Cooking Website: http://www.chamberlaincom.com Weather the Storm Blizzard Books @ Omaha Public Library Picture/Easy Figley, Marty—The Schoolchildren’s Blizzard (picture) Gray, Dianne—Together Apart (fiction) Hart, Alison—Anna’s Blizzard (chapter) Herriges, Ann—Snow (easy) Hurst, Carol—Terrible Storm (picture) Lemke, Donald—Schoolchildren’s Blizzard (graphic novel) Pierce, Terry—Forecasting Fun: Weather Nursery Rhymes (picture) Rustad, Martha—Today Is Snowy (easy) Wright, Betty—The Blizzard (picture) Non-Fiction Breen, Mark—The Kids’ Book of Weather Forecasting Brotak, Ed—Wild About Weather: 50 Wet, Windy and Wonderful Activities Cosgrove, Brian—Weather Dispezio, Michael—Weather Mania: Discovering What’s Up and What’s Coming Down Hopping, Lorraine—Today’s Weather Is: A Book of Experiments Marsico, Katie—Wild Weather Days Murphy, Jim—Blizzard: The Storm That Changed America Rupp, Rebecca—Weather Williams, Judith—How Does the Sun Make Weather Woods, Michael—Blizzards: Disasters Up Close