Power of Propaganda by David Welch

advertisement

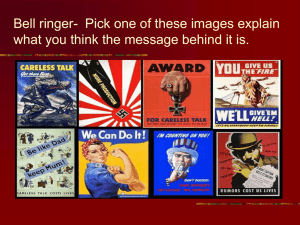

Power of Propaganda by David Welch Source History Today, August 1999 Power of Persuasion - Propaganda David Welch David Welch argues that propaganda has had an essential, and not always dishonourable, role in conduct of affairs in the twentieth century. PROPAGANDA,' SAID ITS MOST NOTORIOUS EXPONENT, Josef Goebbels, `is a much maligned and often misunderstood word. The layman uses it to mean something inferior or even despicable. The word propaganda always has a bitter after-taste.' Goebbels was speaking in March 1933 immediately after his appointment as Minister for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda in Hitler's first government, a role in which he was to do more than most to ensure and perpetuate that `bitter after-taste'. `But,' Goebbels continued: If you examine propaganda's most secret causes, you will come to different conclusions: then there will be no more doubting that the propagandist must be the man with the greatest knowledge of souls. I cannot convince a single person of the necessity of something unless I get to know the soul of that person, unless I understand how to pluck the string in the harp of his soul that must be made to sound. It is ironic that Goebbels should set himself the mission of rescuing propaganda from such misconceptions, for it is largely as a result of Nazi propaganda that it has come to have such pejorative associations. Modern synonyms for propaganda include `lies', `deceit', and `brainwashing'. It is a widely-held belief that propaganda is a cancer in the body politic to be avoided at all costs. But is this really the case? Propaganda in itself is not necessarily something evil. Throughout history the governors have always attempted to influence the way the governed see the world. Propaganda is not simply what the other side does, while one's own side concentrates on `information' or `publicity'. Modern dictatorships have never felt the need to hide from the word in the same way that democracies have done. As the Nazis had their Ministry of Propaganda, so the Soviets had their Propaganda Committee of the Communist Party, while the British had a Ministry of Information, and the USA an Office of War Information. The origins of the word can be traced back to the Reformation. The Catholic Church found itself struggling to maintain and extend its hold in non-Catholic countries. A Commission of Cardinals was set up by Pope Gregory XIII (r. 1572-85), charged with spreading Catholicism and regulating ecclesiastical affairs in non-Catholic lands. A generation later, in 1622, Gregory XV made the Commission permanent, as a sacred congregation de propaganda fide, tasked to manage foreign missions and financed by a `ring tax' assessed on each newlyappointed cardinal. The first official propagandist institute was therefore a body charged with improving the dissemination of a group of religious dogmas. The word `propaganda' came to be applied to any organisation set up to spread a doctrine; then it was applied to the doctrine itself which was being spread; and lastly to the methods employed in the dissemination. During the English Civil Wars, propaganda by pamphlet and news-letter was a regular accessory to military action, Cromwell's army being concerned almost as much with the spread of religious and political doctrines as with victory in the field. The employment of propaganda increased steadily, particularly at times of ideological struggle such as the American War of Independence and the French Revolutionary wars. For example, the Girondist faction distributed broadsheets among enemy troops offering rewards for desertion. In the hundred years from the end of the Napoleonic Wars to the outbreak of the Great War there were no revolutionary wars in Europe, and thus few occasions where intense propaganda, on a national scale, was called for. In 1914-18 the wholesale employment of propaganda by both sides as a weapon of war served to transform its meaning into something sinister. The First World War demonstrated that public opinion could no longer be ignored as a determining factor in the formulation of government policy. Morale came to be recognised as a significant military factor, and in Britain propaganda began to emerge as the principal instrument of control over public opinion. This process culminated in the establishment of the Ministry of Information in 1917 under the press magnate Lord Beaverbrook, and a separate Enemy Propaganda Department at Crewe House under Beaverbrook's rival Lord Northcliffe. By means of strict censorship and tightlycontrolled propaganda campaigns, the press, films, leaflets and posters were all utilised and co-ordinated in an unprecedented way to disseminate `officially' approved themes. Britain's wartime consensus held firm, partly through the skilful use made by the government of propaganda and censorship. After the war, however, mistrust developed on the part of ordinary citizens who realised that conditions at the front had been deliberately obscured behind patriotic slogans and by `atrocity propaganda' that had fabricated obscene stereotypes of the enemy. The population also felt cheated that their sacrifices had .not resulted in the promised `land fit for heroes'. Propaganda became associated with falsehood, and the Ministry of Information was wound up. The government itself regarded propaganda as politically dangerous and even morally unacceptable in peacetime. It was, as one official wrote in the 1920s, `a good word gone wrong -- debauched by the late Lord Northcliffe'. The dislike of propaganda was so deep that when in the Second World War the government attempted to `educate' the population on the existence of Nazi concentration camps, the information was widely suspected of being `propaganda', and not believed. Britain's propaganda in the First World War provided the Germans with a fertile source of counter-propaganda against the Versailles peace treaties and the Weimar Republic. Writing in Mein Kampf, Hitler noted: 'In the year 1915, the enemy started his propaganda among our soldiers. From 1916 it steadily became more intensive, and at the beginning of 1918, it had swollen into a storm cloud. One could now see the effects of this gradual seduction. Our soldiers learned to think the way the enemy wanted them to think.' By maintaining that the German army had not been defeated on the battlefield but had succumbed to a disintegration of its morale, fed by skilful British propaganda, Hitler was providing historical legitimacy for the `stab-in-the-back' legend. Regardless of the true role played by British -- or Bolshevik -- propaganda in Germany's collapse, it was widely believed that Britain's 1914-18 experiment in propaganda had been a great success, and provided the blueprint for other governments to follow. Hitler himself paid the British a compliment when he wrote: Germany had failed to recognise propaganda as a weopon of the first order whereas the British had employed itt with great skill and ingenious deliberation. It was no surprise that he established a Ministry of Propaganda under Goebbels as one of his first acts on assuming power in 1933. The function of propaganda, the Nazi leader argued, was to bring the attention of the masses to certain facts, processes and necessities `whose significance is thus for the first time placed within their field of vision'. Accordingly, propaganda had to be simple, concentrate on as few points as possible, and be repeated frequently, with emphasis on such emotional elements as love and hatred. Through the continuity and sustained uniformity of its application, propaganda would, Hitler concluded, lead to results that are `almost beyond our understanding'. The Bolsheviks, unlike the Nazis, made a distinction between agitation and propaganda. In Soviet Russia, agitation was concerned with influencing the masses through ideas and slogans, while propaganda served to spread the ideology of Marxism-Leninism. The distinction dates back to the Menshevik theorist Plekhanov, who wrote in 1892: 'A propagandist presents many ideas to one or a few persons; an agitator presents only one or a few ideas, but presents them to a whole mass of people.' The Nazis regarded propaganda, by contrast, not merely as an instrument for reaching the Party faithful, but as a means for the persuasion and indoctrination of all Germans. The German propaganda effort under Goebbels was more sophisticated than in 1914-1918. Among methods employed were the setting up of fake `fifth column' radio stations, purporting to be broadcasting from inside Britain, and the use of pro-Nazi Britons to broadcast propaganda from Berlin. London answered with its own `black propaganda' radio stations, partly staffed by Jewish refugees and anti-Nazi exiles from Germany. After 1945, lessons drawn from the Second World War use of propaganda were utilised as part of the wider `communications revolution'. Political scientists and sociologists theorised on the nature of man and modern society -- in the light of the rise of both the consumerist society and totalitarian police states. Individuals were viewed as undifferentiated `and malleable, while an apocalyptic vision of mass society emphasised the alienation of work, the decline of religion and family ties and a general decay in moral values. Culture had been reduced to the lowest common denominator for the purposes of mass consumption and the masses were generally seen as politically apathetic and yet prone to ideological fanaticism and vulnerable to manipulation. Accordingly the view of propaganda shifted again: it was now seen as a `magic bullet' or `hypodermic needle' to enter the thoughts of the masses and control their opinions and behaviour. This bleak view was challenged by American social scientists like Harold Lasswell and Walter Lippman who argued that, within the context of an atomised mass society, propaganda was merely a mechanism for massaging public opinion and acting as a means of social control. Recently, the French sociologist Jacques Ellul has taken this a stage further, arguing that a technological society has so conditioned people that they now feel `a need for propaganda'. In this view, propaganda is most effective when it reinforces already held ideas and beliefs. The notion of the `hypodermic needle' has thus been replaced by a more complex model which, while acknowledging the influence of the mass media, also recognises that individuals seek out opinion formers from within their own class or sex for confirmation of their own ideas and attitudes. Most writers today agree that propaganda confirms rather than converts, and is most effective when its message is in line with the existing opinions and beliefs of those it is aimed at. This change of emphasis highlights a number of common misconceptions about propaganda. It is widely held that propaganda implies nothing more than the art of persuasion, serving only to change ideas and attitudes. More often, though, propaganda is concerned with reinforcing existing trends and beliefs, to sharpen and focus them. A second misconception is that propaganda consists only of lies. In fact it operates with many different kinds of truth -ranging from the outright lie, through half-truths to the truth torn out of context. During conflicts like the Gulf War the British public have been reminded of Dunkirk, the Blitz or the `Falklands spirit'; it has been asked `who governs Britain?' during industrial disputes; it has been assured that inflation can be reduced `at a stroke'; it has been promised that taxes will not rise `under this government' and that `the pound in your pocket' has not, and will not, decrease in value. Since 1997 people have been urged to think of themselves as living in `Cool Britannia'. Propaganda, far from being a malignant growth, is a key part of the political process. Modern political propaganda can be defined as the deliberate attempt to influence the opinions of an audience through the transmission of ideas and values for a specific persuasive purpose, consciously designed to serve the interest of the propagandists and their political masters, either directly or indirectly. In this, propaganda is distinct from information which seeks to transmit facts objectively -- and from education, which hopes to open its students' minds. The aim of propaganda is the opposite: to persuade its subject or public of one point of view; and to close off other options. Propaganda is also limited in its effects. Recent research has examined `resistance' or `immunity' to it. In the short term it may carry its audience away on a wave of fervour; but in the longer term propaganda becomes less effective, as the audience has the time and opportunity to question its assumptions. As Goebbels remarked: `propaganda becomes ineffective the moment we are aware of it'. If propaganda is too rational, it runs the risk of becoming boring; if too emotional or strident it can look absurd. As in other forms of human interaction, to work properly propaganda must strike a balance between reason and emotion. Censorship has been described as both the antithesis of propaganda and its necessary adjunct: but it is a blunt instrument. More subtle forms of propaganda include the plundering of history: London's biggest railway terminus is called Waterloo, and its central square is named Trafalgar; Paris has its Gare d'Austerlitz and its Pont Wagram. Propaganda can manifest itself in the form of a building, a flag, a coin, as well as the more obvious channels of communication. The images of heads of state on stamps and coins offers a ubiquitous reminder of the power of their regimes, and a legitimisation and personalisation of those regimes. As Goebbels maintained, `In propaganda, as in love, anything is permissible which is successful'. Propaganda may be overt or covert, black or white, truthful or mendacious, serious or satirical, rational or emotional. Propagandists assess the context and the audience and use whatever methods they deem the most appropriate and effective. Typically, propaganda will utilise the latest methods of communication. In the First World War this was the press; in the Second, radio and cinema newsreels; post-1945 conflicts have made full use of television. In the war over Kosovo both sides understood the importance of manipulating news to their own advantage. Moreover, the current cutting edge in communications -- the Internet -- has been exploited to disseminate propaganda. Having decided to make war on Serbia -- or, more accurately, on Slobodan Milosevic, `a new Hitler' -- Nato sought to justify its war aims by stressing the `humanitarian goals' of its aerial bombing campaign and the accuracy of its weapons. Jamie Shea, the Nato spokesman, repeatedly insisted: `Our cause is just'. Milosevic also used the media for propaganda purposes. By allowing the BBC and CNN to continue to broadcast from Belgrade he hoped to fragment Western opinion with stories of innocent civilians killed by Nato air strikes. As the most effective propaganda is that which can be verified, Nato was placed on the defensive in the propaganda war when forced to concede the accuracy of some Serb claims of civilian bombing casualties. The Kosovo conflict was only the latest war to reinforce the central importance of propaganda in war, an importance that can only increase in a globalised information environment. E.H. Carr reminded us in 1939: `Power over opinion is not less essential for political purposes than military and economic power, and has always been closely associated with them. The art of persuasion has always been a necessary part of the equipment of a political leader.' If we can divest propaganda of its pejorative associations, we can see its significance as an intrinsic part of the whole political process. Perhaps we need more propaganda, not less, to arouse participation in the democratic process. David Welch is Professor of Modern European History and Director of the Centre for the Study of Propaganda at the University of Kent at Canterbury. His latest publication Germany, Propaganda and Total War 1914-1918 is forthcoming from Athlone/Rutgers UP.3