Prospero and Ariel

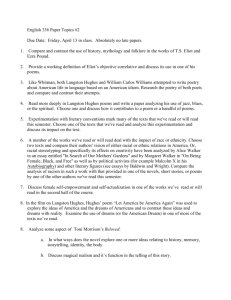

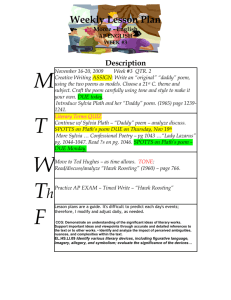

advertisement