glossary - University of Auckland

Glossary and Guide

This glossary is intended to suggest things you might look for and questions

you might ask as you read and discuss literature—although if you can ask entirely new questions, even better. Think of the items mentioned here as tools, lenses, probes, to allow you to look closer and formulate sharper questions.

The discussions are meant simply to help you understand the terms and suggest ways they may be used to notice details in literary works and distinctions between them. The questions at the end of some entries are just some that come to mind: try to think of more.

For many of the terms, I give specific examples. Try to look for different examples, or if general characteristics of an author are mentioned here, try to find particular examples in their works.

The glossary includes not only purely literary terms but also other terms relevant to literature as taught in ENGLISH 111 but not necessarily to other literature courses: linguistic; historical; cognitive and evolutionary; comics and film.

There are many other literary terms, which of course you may use if you know them. The version of the Glossary on Cecil will be updated as needed.

For ease of reference, all entries are in one alphabetical list. You may also wish to cut and paste the files electronically from the Cecil version to make your own subordinate glossaries for different aspects of the course, such as: comics drama evolution and cognition (human nature) fiction film history language literary theory narrative verse writing (your own essay writing)

Any word in bold is a term that can be found in the alphabetical listing. Words in

BOLD SMALL CAPITALS indicate a separate file also available in Cecil that should be useful in discussing literature, comics and film.

Citations are to act, scene and line numbers, or to part and line, or to chapter (in

Pride and Prejudice , to continuous chapter numbers, not volume and chapter), and then if need be to page numbers in the set editions.

Comments that will especially useful to you in reading literature subtly or in writing English well are boxed.

A few books on literary terms can be found on p. 102.

There are many online glossaries of literary terms. Apart from Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page , among the most useful are those of the

English Faculty at Cambridge University, http://www.english.cam.ac.uk/vclass/terms.htm

, and The Literary Encyclopedia: Glossary of Literary Terms : http://www.literaryencyclopedia.com/ http://www.literaryencyclopedia.com/ also has a useful English Style Book: A Guide to the Writing of Scholarly

English at the same URL, which I recommend you consult early and try to assimilate before, and consult while, writing your essay.

64

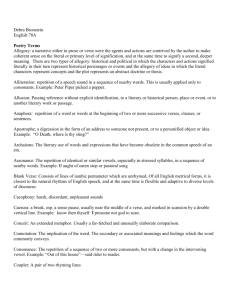

abstract: an abstract noun refers to something that cannot be touched or pointed at: honour , love , war , reason ; its opposite is concrete . (Whether we are aware of these two categories or not, they seem to be stored in different subcompartments of the brain, so it is possible after a stroke to lose the ability to utter and/or understand concrete nouns but not abstract ones, and vice versa).

Writers differ markedly in the proportion of abstract versus concrete nouns they use.

Austen has a strong preference for the abstract (in italics):

Her father captivated by youth and beauty , and that appearance of good humour , which youth and beauty generally give, had married a woman whose weak understanding and illiberal mind , had very early in their marriage put an end to all real affection for her. (XLII, 194)

In Gulliver’s Travels at least, Swift has an even stronger preference for concrete nouns (in SMALL CAPITALS ):

In a little time I felt something alive moving on my left L EG , which advancing greatly forward over my B REAST , came almost up to my C HIN ; when bending my E YES downwards as much as I could, I perceived it to be a human C REATURE not six I NCHES high, with a B OW and A RROW in his H ANDS , and a Q UIVER at his B ACK . (I:1, 23)

Machado can focus mainly on abstract or mainly on concrete, according to his local needs, or combine them as he needs:

Prudencio, a black HOUSEBOY , was my HORSE every day. He’d get down on his HANDS and KNEES , take a CORD in his MOUTH as a BRIDLE

, and I’d climb onto his BACK with a SWITCH in my HAND . . . . I also took a liking to the contemplation of human injustice . (XI)

What effect does the shift from concrete to abstract have here? How does it differ from the next example?

It took me thirty days to get from the Rossio Grande to Marcela’s

HEART , no longer riding the COURSER [= swift horse] of blind desire but the ASS of patience . (XV)

These different preferences for abstract and concrete can be a good indicator of the individual qualities of writers’ imaginations, of what they consider important. (How, do you think?) Or they may reflect local strategic purposes.

(Such as?) How do Machado and Nabokov compare with Swift and Austen in terms of their attention to abstract vs concrete nouns?

Writers also differ in the way they respect or cross the boundaries between the abstract and the concrete. No one crosses boundaries more daringly than Shakespeare. His “That very envy and the tongue of loss / Cried fame and honour on him” ( Twelfth Night 5.1.58-59) couples the very concrete “tongue” (that wet fleshy thing) with the abstract “envy,” to mean in this context “even the envious and those who were crying out to lament their own loss resounded with praise and honor for him.” Dickinson also violates such boundaries in her own way. In “I felt a funeral in my brain,” she writes “And then a plank in reason broke”: the concrete plank seems part of some building or floor of the abstract

Reason. adaptation: In evolutionary biology, a feature of body, mind or behavior that has been especially selected for by natural selection . In humans, our upright posture, our three-colour vision (and the pathways linking more than fifty brain areas that process vision), and language are examples of adaptations, as are our ability to understand other minds as well as we do ( theory of mind ) and emotions like fear, empathy or jealousy. Adaptations, although due to biology, need not be present at birth: teeth, breasts, beards, the bodily and emotional changes at puberty are all biological adaptations shaped by our genes but not present at birth.

Adaptations must serve some function(s) that help(s) organisms with them to reproduce or survive better than they would without them. If, as I suggest, fiction is an adaptation , what functions could it possibly serve? See also

LITERATURE AND EVOLUTION file. adjective: A word describing the qualities of a thing: a dull party, a thrilling lecture. See also GRAMMAR file.

65

Some writers use few adjectives, others many. How do Austen’s adjectives compare with Nabokov’s (“end-of-the-summer mountains, all

hunched up, their heavy Egyptian limbs folded under folds of tawny moth-

eaten plush; oatmeal hills, flecked with green round oaks; a last rufous mountain”)? Machado can use comically overblown adjectives (“the

Caesarean phase” of his romance with Marcela) or direct and even harsh:

“ugly, thin, decrepit.”

In some cases forms of verbs or nouns can be used adjectivally (past participles like “ calculated , cast up , balanced , and proved ,” or a calculating machine, a balancing act, and so on; nouns like Nabokov’s “ picture postcard” or

“ end-of-the-summer mountains”). adverb: A word that qualifies a verb (He ran quickly ; she ran fast .)

In English, often ending in –ly , as in Dickinson’s unexpected and deliberately ungainly coinage New Englandly . See also GRAMMAR .

agent: In narrative theory and in theory of mind , anyone or anything that acts, whether an animal, person, monster, spirit or god. alliteration: The repetition of the initial sounds of words close to one another.

Examples: Shakespeare, Sonnet 73: “And w ith old w oes new w ail my dear time’s w aste”; ) ; Nabokov, Lolita : “ Li ght of m y li fe, fire of m y l oins. M y s in, m y s oul . . . ”

Because alliteration is very easy to identify, students often draw attention to two or three words in proximity that begin with the same sounds, but this occurs very frequently and naturally, just by chance (in this sentence, for instance, without my intending them: “is . . . identify” “same sounds”). Cases as striking as the Shakespeare or Lolita examples certainly deserve comment, but the repetition of a few initial sounds, especially in unstressed words, is rarely worth remark. (Again, I wrote “repetition . . . rarely . . . remark” without planning alliteration, and it hardly makes the sentence special enough to be worth commenting on; same for “sentence special.”)

Notice too that alliteration is repetition of initial sound. It would be not just pointless but an error to claim “certainly deserve comment” two sentences above as an example of alliteration, since the first c has an s sound, the second a k.

In noting alliteration, in other words, you need to ask yourself: why could this possibly matter to readers? If you can see why it makes a difference, say so; if not, is the alliteration worth noting? allusion: a reference to a particular person, event, work of art, character, phrase, etc., existing outside the text.

We all allude to things, especially when we know that those we are talking to know them: a common friend’s peculiar habits, a politician’s latest blunder, a star’s current shenanigans, a line from a song or jingle. It extends our range of common reference, it’s a compliment to what we know or assume others know and share with us. On the other hand those who continually allude to what others in their audience don’t know will be thought show-offs, and will probably lose their audience. It’s the same for writers, but for writers of several hundred years ago (or for political cartoonists several months ago), what was common knowledge then is now much less on everybody’s minds. For that reason, allusions in the works on the course are spelled out in notes, and if you suspect there is an allusion not glossed in this way, then please ask for explanations.

The Bible and other Christian stories, and Classical (Greek and Roman) mythology and literature, are very common sources of allusion in older English literature, as in Shakespeare’s sonnets or Twelfth Night . Donne’s Holy Sonnet “At the round earth’s imagined corners, blow” alludes throughout to the Christian idea of the Last Judgement.

Allusions can be explicit, like the allusion to Walt Disney in Maus , or many in Machado, or implicit, like many in Lolita ; sometimes an author can make hunting for allusions a game of hide and seek, as in Duffy’s poem “Anne

Hathaway,” but rarely are allusions essential to a work unless well known to many readers at the time the works are written. Of course what was well known to the original audience may not be so familiar to a more recent audience from many different backgrounds. altruism: In ordinary usage, generous motives or behaviour towards others; in biology, defined as behaviour offering a benefit to others at a cost to oneself. analogy: Any resemblance a person chooses to make between one thing and another thing unlike the first in important respects.

66

Thought requires the ability to see patterns , natural similarities between things; and contrasts , natural differences between things. Our capacity for analogy allows us to see new relationships, similarities between different kinds of things, and is therefore central to flexible thinking. Metaphor and simile are important types of analogy .

Our capacity for analogy is studied in cognitive science and artificial intelligence . It has been realized that in fact anything may be compared with anything, and it depends on the point of view what likenesses one wants to see.

Despite Shakespeare, “My mistress’ eyes” may in fact be something like the sun:

“spherical,” for instance; or “existing on June 1, 1599” or “objects I have looked at”; and so on.

These are peculiar resemblances, though. But what is surprising is the mind’s capacity to leap to natural and fertile analogies, analogies with cognitive or emotional implications. If I compare “My mistress’ eyes” to the sun, I may mean that when I look into them, they shine, with a light as bright for me as the sun; they seem radiant; they light up my whole life. And others will understand the point of the analogy very quickly. They will not wonder: does he mean his mistress’s eyes are yellow? They will understand the emotional implications, even though the exact correspondence is not clear.

It seems that we share so much as humans that our minds tend to understand almost immediately the analogies that others propose; the unconscious search for a correct interpretation stops as soon as it reaches the correct answer.

However, a highly unusual or bizarre or elaborate analogy may not be comprehensible unless the writer spells out exactly the terms of the analogy. anaphora: A rhetorical device in which words or groups of words are repeated in successive clauses.

In Duffy’s “Row,” each stanza begins with the same line, “But when we rowed.” In this case, the anaphoric repetition serves to stress the recurrence of the lovers’ arguments, yet each “But” implies that this is not the usual tone of their loving relationship. It is much more important to try to explain why a particular effect occurs and works than simply to name it; but names help you to look for possible effects, and invite you to explain them, and make the discussion more efficient. In Duffy’s poem “Cuba,” every sentence begins with the same word: why?

Anglican: The official church of England, established in the 1530s.

From the Latin word for “English.” Historically the Anglican Church or

Church of England was founded when Henry VIII decided to separate the English

Church from the Roman Catholic Church, so that he need not depend on the Pope for the divorce he thought he needed.

Anglo-Saxon: In vocabulary, used to describe words derived from Old English, often short, down-to-earth words (like short , down and earth ) in contrast to a more educated and technical vocabulary derived ultimately from Latin (like contrast , educated , technical , vocabulary , derived , ultimately ).

Anglo-Saxon sweat seems much blunter to us than the Latinate perspiration , and the same for the other well-known words that match the Latinate copulation , defecation , urination . Swift famously contrasts “Celia” (from the Latin for heaven ) with an earthy Anglo-Saxon verb. Good writers use not only the meanings but also the tones and origins and associations (and sounds) of words, and good readers notice them.

You will find the etymologies (word origins) of words in dictionaries, with languages of origin marked usually OE (Old English), ME (Middle English),

Lat. (Latin), and so on. animated film: Any film in which models, drawings, computer-generated images, or other visual subjects are filmed a frame at a time, then repositioned slightly for the next frame, and so on, to create the illusion of motion when the films are reprojected at, usually, 24 frames or more per second. This laborious and expensive method of film-making allows a great deal of creative freedom. antithesis: A figure of speech that highlights contrasting ideas by markedly parallel or contrasting words or arrangement.

Examples: from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129, lust is “Before, a joy proposed, behind, a dream” or “To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell”;

Nabokov’s “Blanche Schwarzmann” (from French for white and German for black ) and

“Melanie Weiss” (from Greek for black and German for white ). apostrophe : As a literary term (rather than as a punctuation symbol), a direct address, especially in poetry, and especially to something or someone other than a live person, as in Donne’s “Busy old fool, unruly sun, / Why dost thou thus . . . ”

(“The Sun Rising”). Among the poets on the course, Wordsworth is particularly

67

fond of it (can you think why, when you get to know his work?): in “It is a beauteous evening” (

S&O

: 6): “Dear Child! dear Girl! that walkest with me here, /

If thou appear untouched by solemn thought”; the next sonnet starts off “O

Friend!” (he has Coleridge in mind); the next, “Milton! thou should’st be living at this hour.” On p. 9, “Surprised by joy,” he says “I turned to share the transport [a spirit of rapture, that transports his imagination or feelings] “—Oh! with whom /

But Thee, deep buried in the silent tomb”: with his daughter who had died a few years previously.

As a punctuation mark, often misused. Correct usage clarifies comprehension and should therefore be followed. Incorrect usage tends to be seen, by those who do understand why apostrophes are used when, as a mark of ignorance or mental muddle or both. If you are not 100% correct in punctuating “were late” (=we are late), “youre wrong” (=you are wrong),

“childs toys,” “childrens playground,” “the dogs tail,” “the dogs tails,” “its tail” and “its late” (for answers, see end of handbook, p. 99), you need to consult the separate APOSTROPHE file and master the principles set out there. art film: A fiction film aimed at a smaller, more select audience than those of

Hollywood and other mass-market movies, and that focuses on the audience’s reflections rather than on action. Usually characterized by slower pace, less explicit and redundant dialogue and cuing of responses, less emphatic and often more fractured storyline, longer takes, more open ending and more openness and ambiguity throughout. Questions: What is the relation of art film to popular film?

What are the borders? To what extent have they cross-fertilized or blended? What is different in attitudes to the audience? Are the categories “art film” and “massmarket movie” hopelessly broad? artificial intelligence (AI): Work in computer science that aims to recreate intelligent behaviour and thought (or at least aspects of intelligence: senses, movement, flexible choice) in computers, partly in order to understand how human thought works.

Because the goal has proved much more difficult than it seemed, it has been helpful in clarifying that many mental processes we assume are simple and immediate are actually complex and multi-layered. assonance: The pointed repetition of similar vowel sounds within close proximity.

Examples: “My heart a ches, and a drowsy numbness p ai ns / My sense . . . b ee chen gr ee n . . . . W i th b ea d e d bubbl e s w i nk i ng at the br i m” (Keats, “Ode to a

Nightingale”). Notice that in English the spelling of similar vowel sounds is almost as likely to be different as similar. Make sure that if you comment on assonance , you are commenting on sounds (and sounds that reflect the way a syllable is naturally stressed or unstressed in a particular word) and not only on similar spellings. assortative mating: The human tendency to choose a mate of more or less the same mate value as oneself (an 8 out of 10, as it were, chooses another 8, or a 7 or a 9, but not a 2 or a 3).

Intelligence and kindness are usually the main criteria preferred by both sexes, but for men youth and looks in women tend to rank next in importance, and for women, resources, status and size in men. attention: Although many social animals benefit from sharing attention (to threats like predators or opportunities like food), humans do so to a unique degree.

From before we are twelve months old, we begin to understand, direct and follow the attention of others through eyes, facial expressions, pointing, sounds, and language. Being able to command the attention of others is a sign of status (think presidents, movie and sports stars), which brings rewards of many kinds. Art in general allows artists to command the attention of audiences, and literature in particular does so through the ability of writers and storytellers to catch and hold the attention and maximize the response of audiences by drawing on our natural attention to others, and by drawing on but playing with an audience’s expectations of language, literature, and human behaviour.

There is a rather narrow limit to the amount we can attend to at any one time: about five to seven “chunks” of information. Writers and other artists make instinctive use of this, not bombarding audiences with too much information at once, but sometimes concealing details or patterns that can add pleasure on later readings, when we can “chunk” what we already know and therefore have the chance to look for new information. attunement: The automatic process whereby our facial expressions and bodily positions and emotions start to match to some degree those whom we see or hear, unless we feel hostile or wary toward them. This process seems to happen very

68

rapidly and unconsciously, so that we often do not even recognize it in ourselves.

It is an essential part of our response to characters on stage, screen or page.

Augustan: In English cultural history, a term applied loosely to the “long eighteenth century” (1660-1780), or especially to the first half of the eighteenth century (1700-1750), and referring to a time that sought to emulate the stability and cultural richness of the era of Augustus, the first Roman emperor, after the turmoil of the Roman Civil Wars (the English Civil War had lasted from 1642 to

1651, and the monarchy was not restored until 1660). It was a time that stressed the value of high civility (which often meant deploring standards that fell short of this). auteur theory: Translation of the French “ politique des auteurs ,” more literally translated “author strategy.” Now an attitude to film-making that stresses the artistic control of the director, it began as a movement among young French film critics of the 1950s (many of whom later became important film directors) to consider standard Hollywood films not as if they were the product of the studios, but as if they embodied the individual directors’ vision. The strategy was therefore first applied to directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks. Prior to this there had been much less consciousness of the director as the artistic shaper of a movie, as the “author” or auteur of its vision and effects, especially in viewing

Hollywood movies from the 1920s on. Questions: Can a director shape a movie as an author shapes a novel? What collaborations and compromises make a fiction film a much less individual effort than, say, a prose fiction? autism: A mental condition, usually noticed in infancy, characterized especially by unresponsiveness to and incomprehension of social cues (like eye movement, facial expression, voice tone, playfulness and deceptiveness).

Many specialists consider it the result of a failure of theory of mind , which is important part of the capacity to understand social actions and stories.

bathos: A sudden drop in level, from the more to the less elevated, especially for comic or satiric effect. biocultural: An approach to the human that accepts both the biological components of our makeup and the role of culture in setting the local parameters of emotions, ideas and behaviour. It stresses that culture arises from society and all societies are societies of living things and hence part of biology, so that it is meaningless to oppose the social or the cultural to the biological. Societies exist only within biology; indeed, the most social animals of all are ants, termites, and bees; human sociality itself derives from the increasing pressure to individualized sociality among primates . Cultures exist only within societies, and are not unique to human societies. There are cultures in many kinds of birds and mammals. Each known wild chimpanzee group has its own unique, culturally-transmitted customs, and could not live without culture. See LITERATURE AND EVOLUTION file. biological determinism: the idea that our biology (often in the form of “our genes”) completely determines our actions.

Often said to be implied by those who accept the existence of a human nature, although no biologist or evolutionary psychologist in fact accepts this.

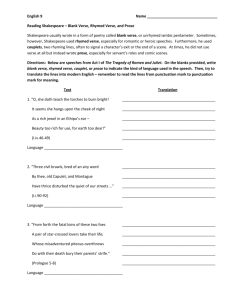

Biology shapes animals, and especially humans, to behave flexibly according to circumstances. One very powerful way of increasing flexibility is through language and culture, which normally-developing humans are biologically adapted to acquire effortlessly at a young age. blank verse: Verse in unrhymed iambic pentameter .

Now almost the normal line of English verse. First used stiffly in plays of the 1580s, and soon developed by Shakespeare into a line of great flexibility.

Little used for non-dramatic verse until Milton ( Paradise Lost ) and his admirers among the Romantics , especially Wordsworth. Not to be confused with free verse . byproduct: A feature of body, mind or behaviour that has not been specially selected for by natural selection but is merely a byproduct of something that has been selected (that is an adaptation). The strength of bone is an adaptation, but its whiteness is a byproduct. canon: The works or authors regarded as important, as classics, as worth studying, and so on, within a particular tradition. To what extent are the works in the canon —the works, for instance, taught at universities—objectively better than those that do not enter the canon ? To what extent is the canon shaped by old habits or prejudices (does it consist of an unfair preponderance of “dead white males”)? The suspicion that women, writers of colour, and those working in genres considered “low art” were under-represented led to the so-called “ canon wars” of

69

the 1980s and 1990s. But is there in fact a canon , or only a host of competing personal rankings, averaged out across those active in the subject? Can any of us choose and promote our own personal canon , or are we guided more than we realize by the judgements of others? caesura: A marked break within a verse line, often indicated by punctuation, as in

Shakespeare’s sonnet 20: “Mine be thy love, and thy love’s use their treasure.”

In scansion , a caesura may be indicated by a vertical line, or a double line: “Mine be thy love, | and thy love’s use their treasure .” characterization: How storytellers let us see characters, and what sort of characters they create.

This is a key aspect of narrative pleasure and narrative style.

A distinction is often made between flat characters and round : flat characters are obvious at first glance, easily summed up, and remain the same; rounded characters are complex, not easily summed up, liable to change or to be seen from different angles. One form of characterization is not necessarily superior to the other, since the effect depends on the author’s local purposes. Mrs Bennett and Mr Collins in Pride and Prejudice are good examples of flat characters, and are all the more enjoyable and memorable because flat.

Note too, that flat characters can unexpectedly become round, and less often, round may become flat. Darcy is a much more rounded character than he seems at first, and Mrs Bennett’s assumption that he is flat (that he is nothing but disagreeably disdainful) is a mark of her limitation. Sir Andrew Aguecheek is a comically diffident fool, yet has moments of confidence, and moments of selfrealization, and moments of vulnerability, that make him more than just what

Shakespeare’s time called a “gull” (a dupe, easily hoodwinked). Vladek

Spiegelman’s difficult character often seems to veer toward caricature (his own fault), yet many of the qualities so irksome in him now helped him then to survive

Auschwitz, and so complicate Art’s feelings and ours toward him.

Another distinction is between central or major characters (such as the hero and heroine) and peripheral or minor . Authors differ on the degree to which they allow minor characters to have rich lives of their own. Antonio in Twelfth

Night has a smallish role to play, yet the depth of his loyalty for Sebastian, and the degree of his bitter disappointment when he thinks Sebastian has denied knowing him, in his hour of need, make him a powerful presence in the play. Austen tends to allow much less life to her minor characters; Elizabeth, Jane and Darcy consume our overwhelming attention. Nabokov focuses attention even more intensely on his central characters (perhaps a critique of their self-obsession?) yet does not overlook minor ones, like John Farlow or Rita. Machado can allow a sudden intensity of response to a peripheral character, like the muleteer or the black slave being beaten by his master Prudencio, himself a freed slave.

Storytellers’ methods of characterization include:

reports of the characters’ actions , speech , and thoughts ;

direct quotations from their speech and thoughts ;

descriptions and/or explanations of the characters, literal or metaphorical;

other characters’ responses to and associations with them ;

the storyteller’s own evaluations of them; and

contrasts with other characters .

Brás’s report of his six-year-old self riding Prudencio like a horse makes a sudden difference to the way we view him ( report of action ). Malvolio’s high-powered disdain for others and acclaim of himself make us all want to see him brought down to size ( quotation of speech and thought ). The visual appearance—the decay, the premature aging—of the older Marcela ( description ) seems to match our moral repugnance, only for Machado to complicate our response with the neighbour’s child’s admiration for Saint Marcela. Sebastian’s ability to inspire the devoted friendship of an Antonio speaks volumes for his character, and prepares us for the devotion that Olivia feels for him (even if she thinks he is Cesario)

( other characters’ responses ).

As a dramatist, Shakespeare cannot comment in his own voice on his characters, though he often has some of his characters comment powerfully on others (on Viola or Malvolio, for instance, in Twelfth Night ). Austen on the other hand never ceases evaluating her characters, and the pungent moral assessments she (like her brighter characters) makes are one of the special charms of her work.

Machado often has Brás Cubas evaluate himself and others, but we have to evaluate Brás’s evaluations ourselves, because although they can be astute, they can be naïve or self-serving, and events themselves may challenge an evaluation.

For character contrast , see next entry.

How do writers differ in their methods of characterization? What do these differences suggest about their interests, or their sense of human nature, or their sense of their audience? What effects do these different methods of characterization have on our response?

70

character contrast: Storytellers often structure their stories not only by events but through the contrast between characters, especially a contrast tightly focused along some thematic line.

Character contrast is a feature of everyday life. We respond differently to others, compare them against one another, think “I would like get to know X better and have as little to do with Y as possible.”

The simplest character contrast reflects the same pattern: heroes, whom we would like to be, or have on our side, and villains, whom we would like not to be, or not to have anywhere where they could impact on us.

More subtle characterization, and more tightly focused, occurs for instance in Twelfth Night , where Orsino’s overconfidence, Sir Andrew’s lack of confidence, and Malvolio’s arrogant and unfounded assurance as prospective lovers is one key to the structure of the play, while another is the gap between

Orsino and Olivia, the woman he professes to love, and the intimacy between

Orsino and Cesario, the young “man” to whom he is ready to unclasp the book of his soul. In Pride and Prejudice Mr Collins’s combination of smarmy selfsatisfaction and fawning servility makes what at first seems like Darcy’s haughty reserve come to seem a much more attractive consciousness of his own real merits of character, and reluctance to display them, and a refusal to respect mere social status. In The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas the differences in moral character between the women in Brás’s love-life, Marcela, Eugenia, Virgilia, and

Eulalia, and the difference between Brás’s relationships with each of them, tell us more than Brás seems to have learned from life. In Lolita the contrasts between

Annabel Leigh and Lolita, between Valeria and Charlotte, between Charlotte and

Lolita, between Lolita and Rita, are all essential to the novel. cheater detection: The alertness to the possibility of cheating in social exchange and the readiness to punish cheaters seem deeply rooted in the human psyche and are a necessary part of the explanation for human cooperation.

See cooperation . chiasmus: A figure of speech in which words are grouped for contrast in a more or less reversed order (AB becomes BA, or some similar reversal), as in

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129: “A bliss in proof, and proved, a very woe” (“in proof” here means “as one experiences it,” and “proved” means “after experiencing”) or

Duffy’s “Rapture”: “Thought of by you all day, I think of you.”

Christianity: The dominant form of religion in the English-speaking tradition, throughout the Middle Ages and, until the 1530s, always Roman Catholic; from then on, more likely to be Anglican or another Protestant sect. For some of its history and central doctrines, see C HRISTIANITY file. cognitive ethology: A branch of animal biology that tries to understand animal thinking, both in the wild and in experiments as close as possible to situations encountered in the wild.

Many things supposed uniquely human, like the capacity to count, to identify and remember faces, and to handle abstractions, have been discovered in many species of animals, proving wrong the assumption that thought is impossible without language.

Cognitive ethology involves long observations of animals in the wild, and their identification as individuals, and careful experiment in situations that test the kinds of skills a particular species is likely to need in its natural habitat. cognitive neuroscience: A branch of human biology that aims to understand in detail how mental processes operate within the brain, where, and in what sequence.

Cognitive neuroscience benefits from many new kinds of brain-imaging devices, such as EEGs (electro-encephalograms), fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) and PET (positron emission tomography) scans, from detailed clinical studies of brain-damaged patients, and from studies of the after-effects of neurosurgery and other medical interventions in the brain. cognitive psychology or cognitive science: A branch of psychology that studies the operations of the mind not in terms of external behaviour but in terms of internal processes, especially as a series of information-processing tasks.

It stresses particularly how much complex processing goes on beneath the level of, and quite inaccessibly to, consciousness. comedy: In medieval times, a story whose outcome was happy, rather than sad, as in tragedy; and by Shakespeare’s time, a story which was often comic or humorous.

The relationship between the happy destination and the humorous route varies considerably from writer to writer.

71

In romantic comedy , the happy outcome involves the pairing-off of at least one couple of lovers (and preferably more). In satiric comedy , such as that of Shakespeare’s great contemporary Ben Jonson, it may involve the unmasking of an impostor. comic: As an adjective, can mean humorous, or comedic (of a comedy).

As a noun, can refer to a story told in successive frames that mix words and pictures.

The different weighting to words and pictures can vary enormously from comic to comic, even within the work of a single artist (contrast the three-page

Maus or the Prisoner on the Hell Planet inset with the book Maus ). Spiegelman spells comics as co-mix to stress both that their defining feature is their mix of the verbal and the visual and to stress that they need not be comic in the sense of

“humorous.”

See COMICS file. comment (see also report, description, speech ): In a narrative text, a passage where the author comments on characters or events or their implications.

The critic Helmut Bonheim usefully distinguished four phases of narrative, depending on their relation to action, the indispensable focus of story.

Any given narrative is likely to include all or most of these.

Speaking itself is an action, and citing the speech directly involves a minimum change: the words of the speaker recur in the words of the text. Other actions, though, are not in verbal form, so in a report on action there will be considerable reworking to tell a sequence of actions in words. Description is even less close to action, since action can be as it were suspended while the scene in which it takes place and the characters who take part are described. Comment is still further from action, since it involves some kind of generalization that may leave the scene entirely.

In the following passage from Lolita , each of the four types will be marked as S, R, D, C before the words the term applies to:

[R] After a while she sat down next to me on the lower step of the back porch and began to pick up the pebbles between her feet—[C] pebbles, my God, [R] then a curled bit of milk-bottle glass resembling a snarling lip—and chuck them at a can. Ping . [S?] You can’t a second time—you can’t hit it—[C] this is agony—[S?] a second time.

Ping . [D] Marvelous skin—[C] oh, marvelous: [D] tender and tanned, not the least blemish.

[C] Sundaes cause acne. The excess of the oily substance called sebum which nourishes the hair follicles of the skin creates, when too profuse, an irritation that opens the way to infection. But nymphets do not have acne although they gorge themselves on rich food. [C] God, what agony, [D] that silky shimmer above her temple grading into bright brown hair. And the little bone twitching at the side of her dust-powdered ankle. [S] “The

McCoo girl? Ginny McCoo? Oh, she’s a fright. And mean. And lame.

Nearly died of polio.” [R] Ping. [D] The glistening tracery of down on her forearm. (I.11)

This is a typical, and typically subtle, passage from Lolita . It comes from

Humbert’s diary, which could therefore all be considered part of his private

“speech,” although it also seems stylized for the reader’s sake into narrative that nevertheless also retains traces of his emotions at the time of the event and at the time of recording it. The changes of tone and distance are remarkable: from the evoked immediacy of “You can’t a second time—you can’t hit it—this is agony— a second time” (did Humbert say that, except for “this is agony,” or only think it?) to the sudden mock-scientific objectivity and remoteness of “The excess of the oily substance called sebum. . . . ” Bonheim’s descriptive terms are elegant and lucid, but original writers invent new resources, new combinations, new intergrades too slippery for any system of classification.

Noticing the different ways in which storytellers use speech , report , description and comment will help you to pinpoint what is unique about storytelling styles. Unlike Hemingway, who uses a remarkably high proportion of speech , and brief report and description , but very little comment ,

Austen uses comment extensively (as even her characters do, commenting in general terms about human behaviour), and description very sparingly.

Machado can use vivid speech , report and description , but Brás also indulges in comment , which may be shrewd or obtuse, distant from us or suddenly close to us:

“Because it was the same thing, dear reader, and if you have ever counted eighteen years, you must certainly remember it was exactly like that.”

Nabokov can often avoid speech for long stretches, or he can mingle description and report and comment . Unlike Austen’s comments , which are usually of a moral nature, provoked by the immediate behaviour of her characters, Nabokov’s comments range more widely over all sorts of things

72

the characters perceive or think about, which may be quite independent of the scenes they find themselves in.

How do these aspects of storytelling reveal the author’s personality, attitudes, or strategies in a particular work? How do they shape our responses to the author and the story? competition: If the world’s resources were infinite there would be no competition.

Because they are not, organisms compete for the finite resources available: energy, food, territory, sexual partners, status, wealth that will purchase other resources, and so on. Even plants compete for sunlight, many growing taller to reach the light first.

Life is not all competition, however. Many organisms (and cells within organisms) can compete much better at one level if they can cooperate better at another. All social life involves both competition and cooperation . comprehension: Our capacity to comprehend life and language involves many mental processes of which we are unconscious. These unconscious processes work with great speed and throw answers up to the conscious mind’s attention. Usually these answers are correct, but if we sense they are not, our unconscious search routines try again, and offer the next most accessible answer. The process continues until we are satisfied or decide to move on.

When we realize that “The horse raced past the barn fell” has a different structure, once we have heard the word “fell,” from what we had expected up to that point, this realization should draw our attention to the fact that even without being aware of it we had already settled on a provisional meaning for the words so far. Computers on the other hand tend to keep all possible options open, so that

“Time flies like an arrow” can be read five entirely different ways.

In understanding language, our minds usually search a speaker’s or writer’s words for the most accessible relevant intention, then stop when we reach it. How our minds search, and how they intuit relevance, are questions we do not yet know the mind in enough detail to answer. But from the difficulty in programming computers to understand simple phrases in natural language, let alone something like the graffito “Ralph, come back, it was only a rash,” we can at least tell that the process is enormously complex and efficient. conceit: As a literary term, this has nothing to do with “self-satisfaction”; it comes from the Italian concetto , “concept,” and means an ingenious image, an improbable and elaborately worked-out image, typical especially of Donne and other metaphysical poets.

Perhaps the most famous of conceits is Donne’s comparison of the souls of two lovers having to part to the two legs of a draughtsman’s compass: “If they

[your soul and mine] be two, they are two so / As stiff twin compasses are two; /

Thy soul, the fixed foot, makes no show / To move, but doth, if th’other do” (“A

Valediction: Forbidding Morning”).

Duffy’s images in Rapture are often close to conceits, in imitation of the extravagant imagery of sonnet sequences. concrete: Concrete nouns refer to particular, tangible things; opposed to abstract . consonance: The presence of similar consonant sounds in neighbouring words.

Examples: “And with old w oe s new wail my dear time’s w a s te”

(Shakespeare, Sonnet 30); “ M otio ns and m ea ns , on land and sea at war . . . T i m e, /

Pleased with your t riu m phs” (Wordsworth, “Steamboats, Viaducts, and

Railways”); “ Every one seemed to be yapping or yipping! / Every one seemed to be beeping or bipping!” (Dr. Seuss, Horton Hears a Who!

); “ L o l i t a, l igh t of m y l i f e, f ire of m y l oins” (Nabokov, Lolita ). consonant: Any speech sound produced by obstructing some part of the flow of air through the vocal tract with the tongue and/or the lips. A consonant can therefore be produced only with another sound (from Latin con , “with” and sonans , “sounding”); opposed to vowel . constructionism: The claim that humans are shaped not by biology but entirely or in all significant ways by society, culture, and/or language.

The main variants are c ultural constructionism , linguistic constructionism and social constructionism .

Opposed to a biological or evolutionary view of human nature, which accepts culture and sociality as parts of biology, and human culture and society as forces that powerfully shape human minds and behaviour, but only because biology has already shaped young human minds to be able to acquire culture and language and to live in human society so effortlessly.

73

content: In literature, the subject-matter of a literary work, as opposed to the shape of the work as a text.

In a successful work of literature content and form should be related in interesting ways. For instance, Twelfth Night ’s multiple plot (an aspect of structure and therefore form ) contrasting the world of Sir Toby Belch, Sir Andrew

Aguecheek and Malvolio with that of Orsino, Olivia and Viola, has interesting effects (such as what?) on the love theme of the main plot (an aspect of content ).

In The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas , the narration from beyond the grave and the addresses to us as readers (an aspect of form ) have consequences crucial for our response to and evaluation of Brás as a character and what he has made of his life (an aspect of content ). Again, what are the implications in this case? How does Spiegelman’s story of his father surviving Auschwitz ( content ) affect the form (the combination of frame story and inset story , of present and past)? context: in literature, a field that can or should be taken into consideration in order to understand a text or part of a text.

Interpreting language always depends on context . “Our mothers bore us” could be part of a proud tribute to motherhood or a teenage complaint, depending on context. In spoken language, the context is always shaped by the situation; in written language, writer and reader do not usually share the same moment of time or point in space. In literary works, which aim to be of interest to readers in many different and unpredictable situations, in many times and places, the most pertinent contexts can be particularly hard to determine.

Contexts exist at many different levels. Within a literary work, they can range from the whole phrase as the immediate context of a word within it, to the situation as a context for an action, to the whole of a text as the context for some detail or pattern to be interpreted (all this I would call the particular

context). Beyond the particular work, contexts can range from other evidence from or about the writer (other works, especially of the same kind or phase in the writer’s oeuvre), the writer’s aims or ideas as expressed elsewhere, the writer’s biography (all this I would call the individual context). Beyond the individual work and the writer, contexts include the genre of which the work is an example, the ideas about literature prevalent at the time, the historical, political, economic, social and intellectual circumstances of the time (local

contexts). Beyond even these contexts are the capacities in humans that make us interested in observing and reporting on each other’s behaviour, telling and listening to stories, and exploring what we can do with language (the

universal context). There is no single “true” context, but readers need to consider which contexts are most likely to make it possible to answer which kinds of questions. When do we sense that the immediate context is not enough? Where do we look next?

Often, context can be important in a negative way: a certain word or idea may simply not have been available at a particular time.

(See also levels of explanation.

) contrast: Contrast enables any information-gathering system, including the human mind, to distinguish one thing from another and make the most of that distinction.

It is therefore essential in literary works: contrasts in mood, in character, in plot, in style are all important to literary effects. The contrast between the mood of one Shakespeare sonnet and another, or one poem and another in Duffy’s Rapture, is vital to the whole sequence, just as the contrast in mood between the first three scenes of Twelfth Night, or between Orsino’s confidence and Sir Andrew Aguecheek’s diffidence, enables Shakespeare to shape our responses, perhaps even without our quite noticing.

See also analogy , character contrast , and pattern . convention: A recurrent feature of works of art within a particular tradition, especially when the feature diverges from what is felt to be natural.

Verse dialogue is a convention of the theatre of Shakespeare’s day, as is soliloquy (especially since we do not usually talk in verse or talk to ourselves at length aloud). A third-person narration in fiction usually involves the convention of the author’s direct access to many points in space and time and to many characters’ thoughts , where in everyday life we have, at best, access only to our own thoughts and only to memories or evidence of the past. A first-person novel overcomes this problem but often involves the convention of perfect recall , whereby a narrator recounts in enormous detail scenes, often complete with exact dialogue, that he or she is supposed to have participated in many years previously.

Conventions abound even in newer forms: in film, for instance, the convention of off-screen ( heterodiegetic , not part of the story world) music , or the convention of shot/reverse-shot editing in filming conversations.

74

Convention is unavoidable and indeed highly desirable in some aspects of communication. Without conventions for sound, sense and syntax, we could not communicate with the ease we do, and conventions of social behaviour minimize uncertainty and friction. But conventions are also sometimes thought to be at odds with the exploratory nature and the freedom of art, and are therefore challenged, parodied, revised, rejected, reinstated.

See also tradition . cooperation: The problem of how cooperation evolved is central to the evolutionary study of social behaviour.

In a competitive world of limited resources, short-term selfishness offers immediate advantages, yet cooperation can offer many kinds of long-term advantages. Since evolution cannot itself plan, look ahead, or select on the basis of the long term, but can select only on the basis of advantage in the present, it is therefore a puzzle how cooperation could have evolved. Yet it clearly has, in many species, and especially in our own, which biologists regard as “ultrasocial.”

Cooperation evolves unproblematically in species like colonies of slime molds, where every organism within the colony shares all its genes with all the other members of the colony; there is no conflict of interest, and if one cells dies in order to provide food resources for its neighbours, it is helping its own genes. In ants, bees, and termites, the genetic relatedness between individuals of the same generation is on the average higher (75% between sisters) than between human parents and children, and again intense cooperation easily evolves. But in the case of vertebrates, including humans, genetic relatedness is at a maximum 50%, between parents and children, and therefore cooperation is more difficult to account for.

Nevertheless, it does happen, and seems to have begun along several lines: 1) inclusive fitness (the genetic relatedness between parent and child, or siblings, 50%, or between one individual and its grandparents, 25%, or uncles and aunts, nephews and nieces, 12.5%). Because of the overlap in our genes, we are naturally far more disposed to help those closely related to us; 2) mutuality , common interests with other members of our species, such as group defence against attack; 3) reciprocal altruism , helping others in return for eventual help from them. This is however subject to the risk of cheating, which can eliminate the advantage; 4) cheater detection , the detection and punishment of cheating, which reduces the short-term advantages of selfishness and therefore strongly encourages cooperation.

Evolution has built into us key social emotions that reflect these various factors that have made cooperation possible: 1) love of kin ; 2) sympathy with others of our kind, where their interests and ours are not in conflict; 3) a sense of fairness and gratitude ; 4) a high wariness for cheating in social exchange, and indignation and anger in response to cheating detected or assumed. couplet: Two consecutive rhyming lines, usually with the same number of feet , as in “There was a young man from Hong Kong / Who thought limericks were too long.”

In his plays Shakespeare often uses couplets to mark the end of a scene, and even to mark speeches where characters think they are about to leave the stage. Thus in Twelfth Night , annoyed at Olivia’s preference for Cesario over himself, Orsino intends to storm off, and punish Cesario:

Come, boy, with me. My thoughts are ripe in mischief.

I’ll sacrifice the lamb that I do love ,

To spite a raven’s heart within a dove .

V IOLA

And I, most jocund, apt, and willing ly ,

To do you rest a thousand deaths would die .

But Olivia keeps them on stage.

Shakespeare’s sonnets always end with couplets . cultural constructionism: The claim, accepted by many, especially in the humanities and social sciences, that humans are entirely or very largely shaped by culture, rather than by biology.

The alternative approach (biocultural or evolutionary ) insists that both biology and culture are important, and that human culture is made possible by factors in human biology.

See also constructionism .

Cultural Critique: A recent term for the currently fashionable approach to literary criticism, focusing on issues of gender, class, race and nation.

Cultural Critique investigates the degrees to which writers accept or challenge the notions of gender, class and race in their time (which are usually

75

taken to be socially constructed). It often seems to assume that these are the only aspects of literature or life worthy of comment. culture: In the biological sense, any behaviour transmitted by ways other than through genes. A culture is a group that shares one particular trait that spreads nongenetically. Rugby culture , for instance, is shared by some people in a number of countries, while New Zealand culture is shared mostly by those in or from New

Zealand; these two cultures intersect but do not coincide. cut: In film, a jump from one take (one continuous sequence of film) to another. dactyl: In metre , a foot with three syllables, unstressed, unstressed, stressed.

Unusual in English, and therefore somewhat emphatic and sometimes comical, as in Dr. Seuss, whose standard line is often a four-dactyl line, with the first unstressed syllable missing.

x / x x / x x / x x /

Too small to be seen by an elephant’s eyes. dangling modifier:

A common error in expression, as in “Reading this poem, the sense is clear.”

Since in English we use position to indicate grammatical relationships, this seems to suggest that “the sense” is somehow reading the poem. (Contrast this with the correct: “Crossing the road, he was struck by a car.” He was indeed crossing, but the sense is not reading.) When we encounter a sentence like this, we can usually work out what the writer means (in this case, that when anyone reads this poem, its sense is clear), but it is always better NOT to make readers do more work than necessary.

Recasting it as “When we read this poem, its sense is clear” or “Reading this poem, we find its sense clear” removes the blockage. decorum: In literature, altering style to make it appropriate to a different form or content.

Shakespeare’s condensed and highly controlled style in his sonnets differs from the freer language of his drama, which has to create the illusion of speech. Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” needs a plain prose style to serve its satiric purpose, while his “The Lady’s Dressing Room” needs an apparently elevated verse style, the couplet , to serve its purpose. (Why?) description: A key element of narrative, whether describing action, character or setting.

Authors differ markedly in the amount and nature of their description, and the degree to which it merges with evaluation. Barnaby

Riche in his “Of Apolonius and Silla,” Shakespeare’s source for Twelfth

Night, represents a common earlier mode of description, in which characters are merely described in terms such as “whose beauty was most peerless”

(Silla) or “who besides the abundance of her wealth and the greatness of her revenues had likewise the sovereignty of all the dames of Constantinople for her beauty” (Julina), so that we can be prepared for the role they are to play in the plot, but cannot imagine them clearly as distinctive individuals. To our taste (or even Shakespeare’s), this seems empty evaluation, not real description.

By the time of the novel, in the eighteenth century, character and setting were usually more particularized. Austen’s characters and settings are individual, but she limits description, at least physical description, to an unusual degree. But her description and evaluation of characters’ moral and social natures are intense, persistent and astute. Machado uses physical description more, but reserves intense description for special cases, like

Marcela in decay or Quincas Borba in his homeless phases, but he also describes character through Brás’s sometimes poorly-focused eyes. Nabokov is different again, using description as a way of reflecting the imaginative and individual quality of the person seeing the scene, whether Humbert, or Lolita or someone else as understood by Humbert, or Charlotte or other characters in their own voices. developmental psychology: A branch of psychology specializing in the development of the mind in infants and children.

New techniques have made it possible to discover aspects of the thinking of very young infants (as young as a few weeks or less) and to understand how they understand the world, and form concepts and categories, long before they understand language. dialogue: An exchange of direct speech between two or more characters.

76

Essential to drama and film, it can also be an important element of action in prose fiction.

Austen tends to render dialogue in a manner that sounds highly formal to our ears. It may be that educated people did speak more formally than they do nowadays, but it is probably more likely that it was simply expected that writers should make their characters as eloquent as they could. This does not stop Austen differentiating characters, of course, so that a Mrs Bennet speaks in a burbling and vapid way that is far from the severity and acuteness of a Darcy.

Dialogue may be realistic , as it can often be in both Machado and

Nabokov, or stylized . Machado stylizes the philosophical exchanges between Brás

Cubas and Quincas Borba for ironic effect. Nabokov milks comic effects from stylization, as in this exchange at the Enchanted Hunters Hotel in Lolita :

”Mr. Potts, do we have any cots left?” Potts, also pink and bald, with white hairs growing out of his ears and other holes, would see what could be done. He came and spoke while I unscrewed my fountain pen.

Impatient Humbert!

“Our double beds are really triple,” Potts cozily said tucking me and my kid in. “One crowded night we had three ladies and a child like yours sleep together. I believe one of the ladies was a disguised man [ my static]. However—would there be a spare cot in 49, Mr. Swine?”

“I think it went to the Swoons,” said Swine, the initial old clown.

( Lolita I.27) diction: In literary analysis, word choice.

An important part of appreciating a writer’s distinctive style. Words may belong to different registers (to formal or even elevated circumstances, or to informal, casual or intimate circumstances, or to a particular technical field, such as the language of sport, meteorology or literary criticism).

English words derive from two main sources, Anglo-Saxon (more likely to be homely, down-to-earth, although sometimes exotic), and Latin (more likely to be technical or educated). Some writers tend to prefer one kind of word more than others, or to combine different kinds of words more sharply than others.

In some periods, such as the eighteenth century, everyday words tended to be thought too vulgar for poetry, or poetic circumlocutions (like “the finny tribe” for fish , in Pope, or “the painted bow” for rainbow ) to be more appropriate than direct statement; in others, such as the Romantic period (roughly 1790-

1830), there has been an attempt to return to everyday language. Nevertheless even the Romantics and their poetic successors rarely use the language of ordinary speech. In poetry the tension between intensity and naturalness is likely to continue in new forms.

See also abstract and concrete , Anglo-Saxon and Latinate . differential parental investment: The relative difference in time and energy it takes males and females to produce offspring capable of surviving to reproduce themselves.

Whichever sex in a given species has the smaller parental investment

(requires less time and energy to produce offspring) will be the more likely to expend more effort in chasing members of the opposite sex as possible sexual partners; whichever sex has the greater parental investment (requires more time and energy) will be the more likely to expend more effort in choosing members of the opposite sex from those pursuing it. In most species, especially mammals, the females have greater parental investment than males and therefore usually choose from the males chasing after them.

Differential parental investment is therefore central to the different attitudes the sexes have towards courtship. disgust: One of the seven primary emotions , an adaptation that evolved to make us avoid polluting substances. In literature, disgust is especially important in satire from Juvenal to Swift (in Books 2 and 4 of Gulliver’s Travels , for instance) and beyond. drama: A form of narrative in which the story is told entirely through the dialogue of the characters, and which is usually intended for enactment on stage.

Closet drama , popular in the Romantic era, is told through the characters’ speeches, but not intended for stage performance. But whatever else they were,

Shakespeare’s plays were scripts for stage performance.

dramatic monologue: A term used by the 19C poet Robert Browning for poems in which the speaker tells his or her own story, often in a way that reveals more of the speaker’s peculiar nature or deeds than he or she is aware of. Duffy also uses the dramatic monologue as a device for characterization and narrative.

77

dramatic irony: The audience’s awareness of key factors of a situation unknown to at least some of the characters in a story.

Twelfth Night is based on several sources of dramatic irony : our awareness that “Cesario” is really a woman; that Sebastian is not really dead; that in the way Viola has dressed in her “Cesario” role, she and Sebastian now look identical; that Sir Toby merely exploits Sir Andrew, and so on. Shakespeare creates the ironies more for their comic effect than their plausibility.

Austen uses much dramatic irony , but tries to make it arise out of characters’ natural misconstructions of others’ attitudes, actions and intentions:

Elizabeth’s (and her family’s) assumption, for instance, that Darcy continues to feel nothing but contempt or condescension toward her, when we know he has become deeply interested in her.

Dramatic irony pervades even simple stories. Our awareness of the reality of the Whos, or of the hurt Gromit feels at being displaced by the Penguin (and our knowledge of the Penguin’s crimes), makes all the difference to our responses to Horton Hears a Who!

or Wallace and Gromit: The Wrong Trousers . editing: In film, the selection, ordering and joining together of filmed footage and soundtrack, both homodiegetic and heterodiegetic .

Often the most serious directors have a hand in the editing of their films. elision: In verse, the omission of part of a word so that it can conform to a poem’s metre ( ne’er for never ; o’er for over ; ’Tis for It is ; on’s for on us , etc.).

Modern poets prefer to evade elision (except those standard in speech, like “I’d”) rather than distort the naturalness of language for metrical effect, but this was not the attitude of poets and readers before the 20C.

Elizabethan: In English history, referring to the reign of Elizabeth I, queen of

England from 1558 to 1603, and in literature, referring to writers active and works composed during her reign.

As a literary period, the Elizabethan age is characterized by a marked secularization (the influence of the Christian church on writing became decidedly less), the emergence of a professional theatre, and an increasing exuberance in writing style. emblem: Originally, a picture with a motto intended as a moral lesson or a subject for meditation, a visible sign of an idea. Machado often uses isolated scenes of an emblematic character, like the black butterfly, the encounter with the muleteer, the finding of the half-doubloon and the mysterious package, the incident of

Prudencio beating his slave, or Romualdo thinking he is Tamerlaine. Brás sometimes supplies a motto, as it were; but often Machado invites us to reflect in our own way, and often to correct what Brás thinks he sees, or does not see. emotion: Where a cultural constructionist would argue that emotions are shaped by culture alone, an evolutionary explanation of emotions sees them as natural adaptations, which evaluate situations and prepare the body and motivate the mind to perform or avoid behaviours that are biologically advantageous or harmful.

Many emotions are widespread among animals (and use the same brain locations and chemical neurotransmitters as in the same human emotions). Recent research has established seven emotions universal in humans— fear, anger, sadness, happiness, disgust, contempt, surprise —that can be recognized by people of all cultures simply from facial expressions.

Note that most of these emotions are negative. Indeed, more of our emotional system is geared to negative situations, since it is more urgent to avoid the bad (danger, especially) than to approach the good (opportunity).

Apart from these basic emotions, mostly shared with many other animals, there are also social and moral emotions , which appear to be less widely shared with animals (although rats and monkeys, for instance, experience empathy), and more subject to fine-tuning by local culture: empathy, love, jealousy, envy, anger, indignation, gratitude, a sense of fairness, for instance. Without empathy, indignation, trust, suspicion, gratitude and fairness, complex cooperation would be impossible.

An important discovery of recent cognitive psychology has been that emotions are not separate from either perception or action. Indeed without emotions, decisions are impossible. People whose emotional centres in the brain have been damaged may be aware of reasons for and against an action, but be unable to stop going over them and to assess or act on the weight of the reasons for or against a course of action. This is important in two ways in literature: it helps us understand the close relationship between the emotions and “reason,” as most writers instinctively have, whatever the culture’s official attitudes to emotion versus reason; and it helps us appreciate that our emotions are necessarily involved as soon as we begin to understand a literary work. Emotions help focus our attention and form a central part of our response to literature.

78

empathy: A feeling of concern for another’s predicament. Essential to the impact of literature, it has been experimentally tested in animals like rats (one rat will forego food if it stops another rat from visibly suffering) and capuchin monkeys and is present from an early age in infants. endstopped: A line of verse whose sense does not carry over strongly into the next line, and which therefore ends with a pause or stop (comma, semicolon, colon, dash, parenthesis, period, etc.).

Endstopped lines may have the thought cross over the line, after a pause, but tend to emphasise the line as a tight unit of thought:

Say, why are beauties praised and honoured most,

The wise man’s passion, and the vain man’s toast?

Why decked with all that land and sea afford,

Why angels called, and angel-like adored? (Pope, Rape of the Lock 5.9-

12)

Contrasted with enjambed lines.

English sonnet: See Shakespearean sonnet . enjambement: Enjambed or run-on lines continue the flow of thought across the end of one verse line into the next, without punctuation.

Enjambement may indicate speed or urgency, or it may simply be normal for a poet trying to preserve much of the naturalness of speech, or just a natural variation even in a poet whose verse is usually end-stopped. What is the effect here?

“O hadst thou, cruel! been content to seize

Hairs less in sight, or any hairs but these!” (Pope, Rape of the Lock

4.175-76)

Contrasted with end-stopped lines. essentialism: The idea that there is such a thing as human nature , or a human essence.

A term of dismissal by those who assume we are (almost) completely culturally or socially constructed (see constructionism and cultural constructionism ) and who are usually unaware of recent work in many fields on human universals . evolution: In biology, the idea that species have not always been fixed but have changed over time. Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection is now regarded as the core unifying idea in biology. evolutionary psychology: The attempt to explain human nature as the result of adaptations shaped by pressures on humans as they evolved. It seeks to know why the processes of the human brain and mind operate as they do. expectation: An evolutionary approach to human nature suggests that minds come with many built-in expectations that allow us to understand our world of experience. From birth infants prefer to look at face-like shapes and already at a day old can imitate adults poking their tongue out, without having ever seen their own face or tongue. We have elaborate expectations—of objects in general, of different kinds of objects, of creatures of our own kind, and of minds—which allow our perceptual and cognitive systems to understand the world efficiently.

These expectations become more fine-tuned by local culture, especially in terms of behaviour and language.

Literature catches our attention by playing on and against our expectations, since the merely expected (like the presence of air, for instance) does not attract our attention, whereas its absence (in the smoke of a fire, or if we choke on food, or if an aeroplane cabin depressurizes) suddenly galvanizes our responses. The following limerick depends on our expectations of the risqué nature of limericks, on our expectations about rhyme, and on our expectations of the social acceptability of words that never even appear in the poem, but that we strongly expect—and that is the joke:

There was a young lady named Tuck

Who had the most terrible luck:

She went out in a punt,

And fell over the front,

And was bit on the leg by a duck. exposition: Information placed early in a story to allow the audience to orient themselves in the situation and to develop expectations about possible directions: the opening page of Horton Hears a Who!

, introducing Horton and his happy character; the opening minute of Wallace and Gromit , introducing the situation of

Gromit’s birthday; Humbert’s explanation of his theory of nymphets; Mrs

79

Bennet’s announcement of the rich young men who have come to the neighbourhood, and her obsession with marrying her daughters off well. A poor writer will dump information on readers; a good one will tend to allow exposition to arise naturally out of the characters and their situations, and to disclose their personalities in action. eyeline match: In film editing, a way of linking images between one cut and what follows to suggest narrative continuity: a character looks off screen in one direction in one shot, and in the next we see, usually, what we infer as what the character was looking at: another person, a pointed gun, whatever. false belief: In psychology, the awareness that others can think things different from what you believe yourself or what you know to be the case.

An important stage in the development of a full human theory of mind .

Children usually reach this stage during the fourth year; no other animal seems to attain this level. An awareness of false belief makes possible dramatic irony , such as our and the onlookers’ amusement at Malvolio’s response to the letter he thinks is Olivia’s declaration of love for him, or our concern for the wrong assumptions that Elizabeth Bennett makes about Darcy’s attitude to her. feminine rhyme: Rhyme involving two rhyming syllables in each line rather than one.

In English, a language poor in rhymes compared with Italian, French or

Russian, the effect is often comic, as in Swift’s “Five hours (and who can do it less in ?) / The haughty Celia spent in dressing ” (also an instance of off rhyme ) or:

Through the town rushed the Mayor, from the east to the west.

But every one seemed to be doing his best.

Every one seemed to be yapping or yipping!

Every one seemed to be beeping or bipping!

(Dr. Seuss, Horton Hears a Who!

)

In general feminine rhyme has nothing to do with female or male

(although Shakespeare, being Shakespeare, cannot resist playing on this: see his sonnet 20), except that female or woman has two syllables, whereas male or man has one.

Contrasted with masculine rhyme . fiction: Any story where the teller and the listener both know the story is not only untrue but is also not meant to be taken as true.

Fiction can be distinguished from various kinds of true narratives

(history, gossip, autobiography) as well as from myth (untrue stories which teller and listener both usually believe to be true) and lies (untrue stories the teller wants the listener to believe).

Fiction includes most drama, feature films and poetry that tells invented stories (like many of Duffy’s poems) as well as novels and short stories. film: For some terms commonly used in describing movies, consult the separate

FILM file. first person: In grammar, first person refers to the person or persons speaking ( I , we , etc.); second person to the person or persons being spoken to ( you , etc.); third person to a person or thing or persons or things being spoken about ( he , she , it , they , etc.),

In narrative , a first person story is one told by a character within the story world, who will therefore feature as an “I.” The Posthumois Memoirs of Brás

Cubas and Lolita are in the first person, Pride and Prejudice in the third person.

See also person , third person. flat characters: see characterization focus: See point of view foot: A unit of verse metre , the equivalent to a bar in music, with a set number of syllables (usually two or three) and a set pattern of stresses.

In English verse, the most common foot is an iamb , which has two syllables, stressed di-DUM (which can be marked x [over the unstressed syllable] /

[over the stressed syllable] when you want to indicate the scansion while using a keyboard, or ˘ [unstressed] / [stressed] when you are writing by hand. form: Used in various ways in literature, especially: a) to indicate a particular kind or genre

80

(in this sense, genre may be a less ambiguous word than form : in form or kind

Twelfth Night is a play, in genre it is a comedy , or more specifically a romantic comedy ); b) as a contrast to content (in this sense, Twelfth Night

’s can be described in terms of its content as a play about love, or about love and self-love, about one-way love, about a sister and brother mistaken for each other, and so on; and in terms of its form as a multi-plot, multi-scene play in mixed verse and prose). frame: In comics , the single panel within which characters and their speech are depicted at a given moment, before the moment featured in the next frame.

Also called panel . frame story: An outer story within which another story is told. In Maus , Art

Spiegelman’s life in the present forms a frame within which Vladek’s and Anya’s life in the past is told. Brás Cubas’s death provides a kind of frame, if not much of a story, for The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas . Dr John Ray, Jr.’s Foreword supplies a different kind of frame again for Lolita . free verse: Verse whose lines have no fixed length, rhythm or rhyme . Not to be confused with blank verse .

Collins’s verse is usually free, although quietly so, since the lines tend to be of much the same length (and much the same length as in most poetry), unlikely the flamboyantly long and short lines of, say, the American nineteenth-century poet Walt Whitman or his twentieth-century successor Allen Ginsberg or the broken lines of twentieth-century American poet Ezra Pound and many of his successors. gender: Often used today to refer to the sex to which a person belongs (male, female, or other possibilities like transsexual and intersexual). In much postmodern Theory , including some kinds of Feminism and Queer Theory, gender is used to stress that human sexual difference is supposedly shaped only by culture, and not by biology. In fact there is good evidence that there are consistent differences between male and female in humans, which reflect differences between male and female also found in many other species. Nevertheless culture can powerfully fine-tune these differences in major ways. But in no human group, for instance, is rape or violence carried out more by females than males, or childrearing more by males than females.