Then he continues

advertisement

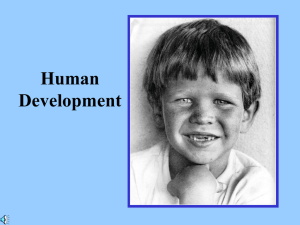

The importance of having parents Introduction A child needs education. Let’s at least assume that. There have been people arguing that a child is a tabula rasa, a blank canvas. On the other hand there have been people arguing that a child is determined from the start, because of its genes. I for one will not deny our genetic passport, so a child is never a totally blank canvas. But studies of so called wild children and other studies have definitively shown that a child needs education. … one can not deny the necessity of education. If you deny this necessity, you proclaim born adultness, full self responsibility of an immature child, and more of such nonsense. 1 Why education? This forces us to think about what education really is or should be. Is there a philosophy of education that we can use here? Let’s try to reflect on three different aspects of education: its values, its goals and its content. According to the Jewish Christian tradition that I rely on, I have to learn, my whole life long. It is not something I can do in my spare time, like a hobby. Instead, it is my duty to learn whether I’m rich or poor, sick or healthy, young or old. Of all the rules for behaviour, learning is the most important. Learning leads to action and becoming a “Tov” person, according to Jewish tradition. “Tov” means not only good in itself, it means good as we are meant to be. It is not important that I am not like mother Teresa. It is about the importance of being me. Learning is not just a command, but a way of living. Learning leads to good practice, and to know what good practice is, you need to study. Good practice means: you know what you are doing, you know how you do it and why you do it.2 Each student has to follow his own path of learning to reach the ultimate goal: to become a “tov” person.3 But in becoming myself as I am meant to be I do not stand alone. I am a part of a community such as my family, my church, my village or my country. I am not being educated in a vacuum. Education is not only individual empowerment but education is by and for this community. The question we have to ask ourselves is what kind of people does our community need? The goal of education is to educate new members of the community. You can not separate education from the community it is in. It is a mistake to think that we are independent individuals. Émile Durkheim states it clearly: Education has to achieve humanness. But not humanness as a natural phenomenon, but humanness the way society wants it. Ans she wants it, as her intern structure needs it.4 In this respect education is always conservative. Hannah Arendt writes about this: Conservatism, in the sense of preserving, is part of the essence of education. Isn’t the goal of education not always to cherish and protect: the child against the world and the world against the child, the new against the old and the old against the new?5 Education is needed for a child as a person, but always for that person as a part of society. But what is it that needs to be learned? Who is the best educator for a child? And what is the role of society in this? These are the questions that need to be answered next. All to often we take the answers to these questions for granted so that we don’t even ask those questions anymore. 6 What is to be learned? If education is by and for this community, what should we teach and what should we learn? What knowledge do we want to pass on? What helps me to become a valuable member of my community? Within our community reality is structured in a certain way. This structure determines what we consider to “be”. But with this “being” a “meaning” is given. It is not only a description but also a prescription. We prefer some values over others. We prefer certain behaviour. Objective knowledge is not possible. Knowledge and values are inseparable.7 Humans are givers of names. These names are not just arbitrary tags, either. In this giving of names there is an inherent calling. It is the calling of creatures and therefore the meaning of those creatures. It is a calling to fight against chaos, which always seems to prevail. Knowledge then becomes a way of creating structure. Passing on knowledge is the way to make our children tread the same path. Then we have to ask ourselves if there is such a thing as absolute knowledge, meant to control reality. Cil Wigmans states this: It seems to be a dilemma. The secularisation that took place in our western world in the past centuries is a blessing and a curse. It liberated us from the unjust claim of those who forced upon us, what they said God wanted. The powerful have come down from their thrones. But the meek didn’t come to power. Instead came the claim of the laws of nature, the power sui generis, or the will of people, that grant power far too often to those who promise mountains of gold (or as the bible says: golden calves). The wealth of Egypt is chosen over the dangers of the desert. These false powers are idols.8 Therefore we have to think of ways to structure chaos without praying to those idols. The best way to do that is by telling stories. Stories that stand in a long line of common, shared tradition. Therefore we need teachers that stand in this tradition themselves. On the other hand there is room in these stories for the listener, the receiver. The receiver will have to travel his own path.9 In the bible Psalm 78 gives us a beautiful example: “He decreed statutes for Jacob and established the law in Israel, which he commanded our forefathers to teach their children, so the next generation would know them, even the children yet to be born, and they in turn would tell their children. Then they would put their trust in God and would not forget his deeds but would keep his commands. They would not be like their forefathers – a stubborn and rebellious generation, whose hearts were not loyal to God, whose spirits were not faithful to him.” 10 The bible book Isaiah says: “Those who hope in the LORD will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles.” 11 Traditional education wants to create clones. It wants to copy the achievements of the past generations. It spasmodically maintains the existing order. But that is conservatism without any foundation, without a starting point. It has no moral point of reference. So we have to take it from a different perspective entirely. We have to choose a starting point in our worldview. Very early in the Old Testament the idea comes up that the Torah also opens the future. The biblical God is a God of history, but also of hope and renewal. In the perspective of psalm 78 carrying over tradition from one generation to another is not “look how well we have don and what we have achieved. We expect you to take over and do exactly the same.” No, it is about taking over the essentials of life from your ancestors and walk your own way. It is about handing over the essentials of life, knowing that perhaps you didn’t live up to it yourself. And you hope that your children will do better. Then you need to let go and give them the space to grow.12 Who educates? Every child is born from a man and a woman. That is no moral statement but just a biological fact. Those 2 people than make the most logical primary educators. This is the core family of a father and a mother with one or more children. From the beginning of a child’s life it is educated by these biologically attached people. It comes naturally. From very early civilisations we can plainly see that there are always other people involved. The Greek had their pedagogues, slaves that could educate children. The Jews had their Beth ha Midrasj, the house of learning, apart from the synagogue. We in modern society have our schools.13 In all those places and times education was never purely transfer of objective knowledge or practical skills. Education has always been a vehicle for worldview aiming for the improvement of the community. Its aim is to make the new generation responsible members of that community. The person that pretends to educate, opposes himself to the newcomer as responsible for the word. If his does not like this responsibility, he would better devote himself to something else, with which he does not stand in the way of someone. To make yourself responsible for the world is not the same as approving the world as it is. It means to accept the world in full awareness because she is and because one can improve it only by starting at what she is. 14 But in all this parents remain responsible for the education of the child. It is not the state, the church or any other institution that is primary responsible. Parents hand over some of the responsibility for education to others, but they are the ones that form the basis of education. Why? Because of love. The basis of a family is love. Unconditional love. Other people may give love, but that is not the same as the unconditional love that parents have for their children. For the benefit of whom? I think that this is exactly the point where we begin to feel uncomfortable in modern society. More than ever we feel first of all that we are individuals. We want to be independent. We want to be unique. We don’t want to be part of a mass. We want to be free. We know what is good for ourselves and for our children. We don’t want anyone else to interfere and mess with that. We don’t want anyone else to spoil the loving care we give to our children. Society seems to be more of a threat than a benefit for our children. The individualistic lifestyle reflects on the way we educate our children. Society now sees children as some kind of hobby. Even sometimes an old-fashioned kind of hobby. A hobby is one’s own choice, not something that society should be bothered by or spend money on. If people, and even more specific sometimes: women, want to have children, they have to bear the consequences of their choice, both in the sense of investment in time and money. This should not be a political concern, so is said. Many of these individuals reject the very notion of a good society. Societies, they maintain, flourish when individuals are granted as much autonomy as possible. 15 But this is a denial of society as a community. Society is not just a group of individuals, coincidentally living in the same time and place. The communitarian paradigm … applies the notion of the golden rule at the societal level, to characterize the good society as one that nourishes both social virtues and individual rights. 16 This has its consequences for public policy and public investments. I argue that education should be free, costless. In the end, by means of financing education, a society invests in its own existence and future. Seeing education as commodity that you can buy is wrong. If it works that way, the best education goes only to those that can pay for it, instead of to the ones that need it for the benefit of the community. It is wrong when schools see parents only as the people that pay for the education of their children; like some kind consumers. But did you know that much of a child’s achievement depends on good parenting? For good school achievement parent participation is even more important than the influence of the teachers. 17 I call upon our governments: wake up! Invest in education. Invest in families and their support and invest in schools. Maturation Sharon Willmer, therapist and full-time college lecturer with over thirty-years of experience, notes, The problems of today’s youth (and the accelerating cultural deterioration) are primarily a problem of Maturation. That is both the good and bad news. It is good because it can be understood and addressed with tremendous success. The bad news is the deterioration is generational and accelerating. Therefore, time is of the essence.18 In seizing the moment, just maybe we can galvanize sufficient will among decision-makers and the general public to actually change the trajectory of our culture. Just maybe, we can change the narrative so that even as we lament problems of our Gross Domestic Product, we are developing the Social Capital to build an ever increasing Gross Maturation Product. While not a totally new idea, as the following excerpt from a speech given by the late Robert Kennedy, given in 1968, attests. It is a noble calling that is even more relevant today than when he spoke these words 40 years ago. The gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country, it measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.19 Background and Rationale Primary concern: Underachievement – regardless of how much money we spend. In terms of academic performance, in the 1950s the American educational system was largely regarded as the “envy of the world.” In contrast, today the United States is merely average for the industrialized world. 20 The problems are particularly acute in our large urban school districts where nearly half of all students do not graduate from high school on time. Not only is this tragic for the students themselves it is costly to society. For example, it is estimated that over their lifetimes, dropouts from the class of 2007 alone will cost the Nation more than $300 billion in lost wages, lost tax revenue, and lost productivity.21 Even the military is finding there is a widespread problem with young recruits lacking basic math and reading proficiency so that many are unable to pass a military service entrance exam required for all enlistees.22 Beyond underachievement – Deteriorating social indicators (and they are not limited to children living in poverty). Concern over schools is difficult to separate from broader concerns about the lack of well-being in our youth. Unfortunately, what we see is troubling. “We are witnessing high and rising rates of depression, anxiety, attention deficit, conduct disorders, thoughts of suicide and other serious mental, emotional and behavioral problems among U.S. children and adolescents,”23 asserted a path-breaking, interdisciplinary study: Hardwired to Connect: The New Scientific Case for Authoritative Communities. The following trends illustrate this deterioration in the well-being of children and adolescents: Teen suicides are the third greatest health threat to adolescents. At a number of the schools drawing from our wealthiest communities, students experience hyper-pressure to perform in academics, sports, and other extra-curricular activities with reportedly increasing numbers of students experiencing high levels of stress and depression – some severe enough to cause attempted suicides. 24 Rampant cheating. It is difficult to assess actual levels of student achievement because cheating is rampant and has increased dramatically over the last 60+ years. In recent surveys, between 75 and 98 percent of college students report that they cheated in high school. This statistic is even more alarming, when compared with surveys taken during the 1940s, where approximately 20 percent of college students admitted that they had cheated in high school.25 Isolation and bullying. The isolation of youth into an often narcissistic social networking world, with a variety of detrimental effects, including bullying, as well as a lack of analytical and higher-level thinking skills, civic engagement, etc.26 Lack of identity and purpose. Naomi Schaeffer Riley points out in God on the Quad, “Academic insiders and outsiders alike have described a certain malaise among today’s college students.” 27 The “Emerging Adult” (EA) phenomenon. Where “26 is the new 18” with many young people taking on traditional adult responsibilities at much later ages than their counterparts in previous generations. The corrective – Expanding our understanding of maturation and its relational mandates. As a culture, it is important to move beyond merely focusing on troubling behavioral indicators to find root causes and preventative models that can inform successful strategies. Yet this approach necessitates adults looking at the content of how they are guiding the next generation as well as the roles they play, in guiding young people – whether their role is that of parent, teacher, school administrator, advertising executive, politician, church or community leader, etc. It then can become difficult to find an approach that gains widespread acceptance, in our increasingly polarized, post-modern environment where discussing norms and values is difficult, if not impossible. Fortunately, the language of relational health, its developmental process and the tools/maturation to secure it provides an important lens through which to build a workable, engaging framework. Some of the ground work has already been laid: The Hardwired to Connect report has made inroads in building a case for supporting and empowering primary social institutions (i.e. family, religious and community-based institutions), which it describes as authoritative communities. It promotes these social institutions, as the ideal vehicles for fostering maturity in our youth. In fact, it concluded that the deteriorating mental and behavioral health of U.S. children is due, at its core, to a lack of “connectedness” and found a correlation between the weakening of these primary social institutions over the last several decades, and the escalation of problems associated with at-risk children. These social institutions are comprised of “groups of people (primarily nonprofessionals) who are committed to one another over time and who model and pass on at least part of what it means to be a good person and live a good life” to the next generation. The report affirms the important, irreplaceable role played by family and community stakeholders in nurturing and supporting youth. It also points to the necessity of helping children connect to moral and spiritual meaning as an antidote to destructive personal behavior.28 A recent report from the Relationships Foundation (U.K.) has broken new ground by illuminating and making accessible cutting-edge research (particularly from developmental psychology and neuroscience) on maturation and its relational mandates. The value of this work is its winsome description and vision of the qualities we want to instill in our youth. When faced with our natural longings for our children’s and our culture’s well-being, the report has the potential to break through the preconceived notions of postmodernists. It does not explicitly refer to Biblical texts of doctrine, but certainly supports Orthodox Christian faith, and elucidates further some of its most sacred beliefs. The report describes maturation as follows: Maturation is a vibrant, dynamic process, and when on target, it presents with an increasing stability, agency, soft skills, and capacity to navigate life. Adulthood, with all of its demands, pleasures, pains and difficulties needs to be able to rely upon a basic foundation of maturation. Indeed, maturation (healthy development) is the foundation for healthy family, individuals, community and governing.29 The Relationships Foundation report further lays out a maturation model that is relationally driven and based on the following five pillars: Attachment – Starting at birth, attachment is a lifelong, cumulative process which organizes the structure of the brain and affects the capacities we have to relate to people. 30 Affect regulation – The process of learning to control the raw feelings that characterize early infanthood and expressing them in ways that are socially acceptable and safe.31 Cognitive development – This pillar includes both skills and knowledge that are an essential platform for navigating life as well as providing the necessary capacity to know ourselves, others, establish meaning and purpose and engage with thoughtfulness in society.32 Moral development – Morality is fundamentally about how we attach and is mandatory to maturation, wellbeing, stable identity, healthy relationships and civil society. 33 Identity – Development which progresses to the awareness that we are a distinct person with a growing narrative of the self which includes what we genetically inherit and the physical and relational contexts in which we develop. 34 Lessons learned from tackling the most pronounced failing schools. The window for substantial education reform cracked open in early fall of 2010, when two widely acclaimed, high-profile documentaries, Waiting for Superman and The Lottery, catalyzed a national conversation on education. Both films focus primarily (although not exclusively) on tragically underperforming, urban public schools – where over half the students do not graduate and many who do graduate are functionally illiterate. In the past, the problems have been perceived by many to be so pervasive and intractable and the stakeholders of the status quo so firmly established, that as a nation, we have tolerated a dysfunctional system and widespread failure. In order to improve education governments and schoolboards can spend lots of money on improving the schools, but according to Henderson and Mapp the keyfactor to improving schoolachievement is the involvement of parents. Size of class 8% Teacher quality 43% Family and home 49% Mitch Pearlstein, author of From Family Collapse to America's Decline: The Educational, Economic, and Social Costs of Family Fragmentation laments the self-perpetuating nature of family fragmentation and its particularly devastating effects on the poor, and like Whitman suggests that schools could have a role in reversing this Henderson trend. He states, “In communities where “marriage is vanishing, it cannot be revived unless millions of boys (and girls) get their lives in decent order.” Then he continues: Many of these young men grew up without their fathers and suffered what some call “father wounds.” Would it not make sense for such boys to attend schools properly described as “paternalistic”? These would be tough-loving places, like the celebrated (but still too few) KIPP and Academies, with their Knowledge Is Power Program. Would it not also make sense to allow many more boys and girls to attend religious and other private schools, which have their “biggest impact,” according to Harvard’s Paul Peterson, by keeping minority kids in “an educational environment that sustains them through graduation”? 35 The principles hold true, irrespective of socioeconomic status. Samuel Casey Carter studied the cultures of more than 3,500 schools across the US, serving communities from a variety of socioeconomic levels. His conclusions paralleled Whitman and Pearlstein’s, noting that there is a strong link between a school culture that is simultaneously nurturing while demanding high academic and behavior standards and student growth. Carter describes students in these environments as experiencing “a renewed sense of self and an individual sense of purpose that can then be tapped to drive remarkable student achievement." Clarity, regarding what a relational school is NOT: An approach that idolizes and over-emphasizes cultivation of self-esteem in children. (This trend in recent years, has actually led to increased anxiety and narcissism. 36 Nor is it a “boot camp” characterized by harsh, authoritarian adults establishing punitive rules on children and adolescents – which like its overly lax counterpart does not facilitate maturation.37 It is, instead: An environment that is both nurturing and challenging, that invites students into higher levels of maturation – a life-long journey, (as opposed to merely checking off chronological or developmental milestones) that unfolds for every person from within and without establishing patterns of behavior, relationships and character.38 James Coleman, one of the leading sociologists of education in the late 20th century, described at length the extent to which in recent years, “the family has become a peripheral institution, along with the remnants of communities that were once the center of social and economic life.” As it relates to schools, Coleman saw two stark options: On the one hand, we can “accept [the demise of families], and to substitute for them new institutions of socialization, far more powerful than the schools we know, institutions as yet unknown.”39 Or, alternatively, (and the position that Coleman advocated), we can ….strengthen the family’s capacity to raise its children, building upon the fragments of communities that continue to exist among families, and searching for potential communities of interest.40 Nevertheless, even with the limitations of functioning within a public system, there are numerous examples of individual schools creating meaningful partnerships between parents and teachers, resulting in improved outcomes for students. David Whitman’s book includes University Park High School in Worcester, Mass., a neighborhood-based, public high school. Moreover, Dr. James P. Comer, the founder and chairman of the School Development Program at the Yale University School of Medicine's Child Study Center pioneered the Comer School Development Program. Since 1968, he has been working in numerous public schools across the country to build relational “operating system” in public schools that foster collaboration and active partnership between parents, educators and community resources with a goal of improving social and emotional outcomes of children – a necessary prerequisite (especially for children whom he describes as “school dependent”) to their academic achievement.41 Next Steps Although, as described above, there have been exciting advances in this area, more work needs to be pulled together so that we can offer a framework that illuminates our understanding of maturation, in all its fullness, that will provide guidance around which we evaluate the developmental challenges that our children and youth face as well as the vital role that supportive adult relationships have in propelling them forward. Great care needs to be given in identifying what roles adults play that actually infantilize our youth and children, rather than inviting them into higher levels of maturity. Moreover, since vision is more often “caught” than merely “taught”, it is important that adults model for their students maturity and relational health in their working relationships with other adults as well as with their students. Having clarity on their respective roles, from which emanate healthy boundaries is important to clarify. For further reading Abram, I.B.H., 1986, Joodse traditie als permanent leren, Kok, Kampen Ahrend, Hannah, 1968 Revised edition, Between Past and Future, Viking Press, New York Baartman, H.E.M., J.E. Doek, N. Draijer, W. Koops en K.J. de Ruyter, 1997, Gezinnen onder druk – over veranderende ouder-kindrelaties; hoe moeilijk/gewoon opvoeden kan zijn, Kok Agora, Kampen Daniels, Harry, 2001, Vygotsky and pedagogy, 2006, RoutledgeFalmer, London Dasberg, Lea, 1984, Grootbrengen door kleinhouden als historisch verschijnsel, Boom, Meppel Desforges, D., and Abouchaar, A., 2003, The impact of parental involvement on pupil achievement, DfES Research Report 433 Durkheim Émile, 1956, Education and Sociology, Free Press Hoog, C. de, A.W. Musschenga, C.D. Saal en R. Veenhoven, 1985, Gezin: ideaal of alternatief, Bosch & Keuning, Baarn Etzioni, Amitai, 1996, The New Golden Rule: Community And Morality In A Democratic Society, Basic Books, New York Jongma-Roelants, Toos en Peter Cuyver (Red.), 1995, Gezinnen van deze tijd – Kinderen, cultuur, rolpatronen, Kok, Kampen Kennedy-Doonbos, Simone en Geert Jan Spijker (Red), 2008, Samen de schouders eronder – Christelijk-sociale visie op gezin en werk, Mr. G. Groen van Prinstererstichting – wetenschappelijk instituut van de ChristenUnie, Amersfoort Langeveld, M.J., 1974, Beknopte theoretische pedagogiek, Wolters-Noordhoff, Groningen Lodewijks-Frenken, Els, 1984, Op opvoeding aangewezen: een kritiek op de wijze van omgaan met kinderen in onze kultuur, Nelissen, Baarn Logister, Louis (Red.), 2005, John Dewey – een inleiding in zijn filosofie, Damon, Budel Noordam, N.F., 1976, Inleiding in de historische pedagogiek, Wolters-Noordhoff, Groningen Ritzen, R, 2004, Filosofie van het onderwijs. Een analyse van acht hoofdvragen, Damon, Budel Savater, Fernando, 1997, El Valor de Educar, Ariel, Barcelona. Dutch translation : 2006, De waarde van opvoeden, Bijleveld, Utrecht Taylor, Charles, 1989, Sources of The Self – The Making of the Modern Identity, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts Wetenschappelijk Instituut voor het CDA (Red.), 1996, Familie en gezinsbeleid, Wetenschappelijk Instituut voor het CDA, Den Haag Wigmans, C.M., 2004, De oude wortels van het nieuwe leren. Bouwstenen voor geïnspireerd onderwijs, Scope scholengroep, Alphen aan den Rijn Woudenberg, R. van (red.), 1996, Kennis en werkelijkheid. Tweede inleiding tot een christelijke filosofie, Buijten en Schipperheijn, Amsterdam 1 Langeveld, M.J., 1974, Beknopte theoretische pedagogiek, Wolters-Noordhoff, Groningen Abram, I.B.H., 1986, Joodse traditie als permanent leren, Kok, Kampen 3 Abram, I.B.H., 1986, Joodse traditie als permanent leren, Kok, Kampen 4 Durkheim Émile, 1956, Education and Sociology, Free Press 5 Ahrend, Hannah, 1968 Revised edition, Between Past and Future, Viking Press, New York 6 Ritzen, R, 2004, Filosofie van het onderwijs. Een analyse van acht hoofdvragen, Damon, Budel 7 See the explanation of the theory of Transcendent Critic by H. Dooyeweerd in Woudenberg, R. van (red.), 1996, Kennis en werkelijkheid. Tweede inleiding tot een christelijke filosofie, Buijten en Schipperheijn, Amsterdam 8 Wigmans, C.M., 2004, De oude wortels van het nieuwe leren. Bouwstenen voor geïnspireerd onderwijs, Scope scholengroep, Alphen aan den Rijn 9 Wigmans, C.M., 2004, De oude wortels van het nieuwe leren. Bouwstenen voor geïnspireerd onderwijs, Scope scholengroep, Alphen aan den Rijn 10 Psalm 78:5-8 11 Isaiah 40:31 12 Buijs, G., 2005, Spanning in de familie – een portret, Nederlands Dagblad 13 More examples you can find in Noordam, N.F., 1976, Inleiding in de historische pedagogiek, WoltersNoordhoff, Groningen 2 14 Savater, Fernando, 1997, El Valor de Educar, Ariel, Barcelona. Dutch translation : 2006, De waarde van opvoeden, Bijleveld, Utrecht 15 Etzioni, Amitai, 1996, The New Golden Rule: Community And Morality In A Democratic Society, Basic Books, New York 16 Etzioni, Amitai, 1996, The New Golden Rule: Community And Morality In A Democratic Society, Basic Books, New York 17 According to the research of Sacker et al in Desforges, D., and Abouchaar, A., 2003, The impact of parental involvement on pupil achievement, DfES Research Report 433 18 Sharon Willmer and John Ashcroft, The Connection between Development, Quality of Family Relationships and Public Benefit: The Policy Response, The Relationships Foundation, p. 2 (draft edition) 19 Robert F. Kennedy at the University of Kansas, March 1968 20 Peterson, Saving Schools, pp. 9-10. 21 Innovations in Compassion: The Faith-Based and Community Initiative: A Final Report to the Armies of Compassion, White House Report, December 2008. 22 Otto Kirschner, “Armed Services Having Trouble Finding Qualified Recruits,” Congress Daily, March 24, 2008 as reported in A Family-based Social Contract, by Phillip Longman and David Gray, November 2008. 23 Hardwired to Connect, p. 5. 24 Road to Nowhere (Documentary) 25 The Center for Academic Integrity, www.academicintegrity.org/cai_research.asp 26 Mark Bauerlein, The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupifies Young Americans and Jeopardizes our Future. 27 Quoting from a 2002 NY Times article that profiled Jeffrey Lorch, one of 2,600 Columbia University students who had sought help at the counselling center. Schwartz described Lorch as saying it took three quadruple Expressos and an unknown quantity of Prozac to make it through the day. She also quoted him as lamenting, “There have been times when I’ve felt like every conversation [I’ve had at school] has been a sham.” 28 The report defines authoritative communities as “groups of people who are committed to one another over time and who model and pass on at least part of what it means to be a good person and live a good life” to the next generation, p.6. 29 The Connection between Development, Quality of Family Relationships and Public Benefit: The Policy Response, The Relationships Foundation (U.K.), Sharon Willmer and John Ashcroft, p.4 (draft edition). 30 Ibid, p.22. 31 Ibid, p.29. 32 Ibid, p.4. 33 Ibid, p.41. 34 Ibid, p.4. 35 Mitch Pearlstein, “Broken Families, Broken Economy: The Real Obstacle to Growth,” in The Weekly Standard, July 11, 2011, 37. 36 Jean Twenge, Generation Me: Why Today's Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled–and More Miserable Than Ever Before, Free Press, April 2006 37 Robert Epstein, Teen 2.0: Saving Our Children and Families from the Torment of Adolescence, Quill Drive Books. 38 Willmer and Ashcroft. 39 James S. Coleman, University of Chicago’s 1985 Ryerson Lecture, “Schools, Families, and Children” (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago, 1985), 17 as quoted in Jack Klenk, Who Should Decide How Children are Educated? 40 Coleman, “Schools, Families and Children,”18. 41 Dr. Comer defines “school dependent” as those students (more often Black or Hispanic) who live in lowincome communities without the same levels of libraries and