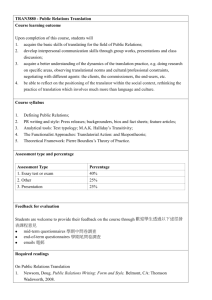

INTRODUCTION - College of Social Sciences and International

advertisement