A Silicon Valley School That Doesn`t Compute

advertisement

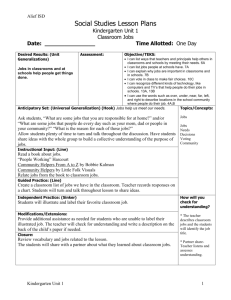

Technology in School PRACTICE COMMON CORE ASSESSMENT TEXT BOOKLET Context: In 2010, Arne Duncan, the United States’ Secretary of education sent a letter to Congress saying, “I urge you to consider … transforming American education by using the best and most inclusive modern technology.” He argues that increasing digital technology in our nation’s classrooms will make America more competitive. That’s why millions of dollars are being invested in bringing more technology into our schools. At the same time, brain scientists warn that our increasing use of digital technology may be leading to shorter attention spans and difficulty engaging in deep learning. They say people’s brains are getting “re-wired” to be more distracted. The debate continues: should our school system increase or decrease digital technology in classrooms? During this assessment, you will watch a video and read several articles about this issue. This booklet contains space for note-taking, places to briefly answer questions about the articles, and room for drafting and revising an essay. DO NOT OPEN BOOKLET UNTIL INSTRUCTED TO DO SO Text #1 8 Ways Technology Is Improving Education This article was adapted from an article written by Sarah Kessler Nov 22, 2010 The Education Tech Series is supported by Dell The Power To Do More, where you'll find perspectives, trends and stories that inspire Dell to create technology solutions that work harder for its customers so they can do and achieve more. Don Knezek, the CEO of the International Society for Technology in Education, compares education without technology to the medical profession without technology. “If in 1970 you had knee surgery, you got a huge scar,” he says. “Now, if you have knee surgery you have two little dots.” Technology is helping teachers to expand beyond linear, text-based learning and to engage students who learn best in other ways. Its role in schools has evolved from a contained “computer class” into a versatile learning tool that could change how we demonstrate concepts, assign projects and assess progress. Despite these opportunities, adoption of technology by schools is still anything but ubiquitous. Knezek says that U.S. schools are still asking if they should incorporate more technology, while other countries are asking how. But in the following eight areas, technology has shown its potential for improving education. 1. Better Simulations and Models Digital simulations and models can help teachers explain concepts that are too big or too small, or processes that happen too quickly or too slowly to demonstrate in a physical classroom. The Concord Consortium, a non-profit organization that develops technologies for math, science and engineering education, has been a leader in developing free, open source software that teachers can use to model concepts…[The] organization is developing include a software that allows students to experiment with virtual greenhouses in order to understand evolution, a software that helps students understand the physics of energy efficiency by designing a model house, and simulations of how electrons interact with matter. Notes on my thoughts, reactions and questions as I read: 2. Global Learning At sites like Glovico.org, students can set up language lessons with a native speaker who lives in another country and attend the lessons via videoconferencing. Learning from a native speaker, learning through social interaction, and being exposed to another culture's perspective are all incredible educational advantages that were once only available to those who could foot a travel bill. Now, setting up a language exchange is as easy as making a videoconferencing call. 3. Virtual Manipulatives Let's say you're learning about the relationship between fractions, percents and decimals. Your teacher could have you draw graphs or do a series of problems that changes just one variable in the same equation. Or she could give you a "virtual manipulative" and let you experiment with equations to reach an understanding of the relationship. "You used to count blocks or beads," says Lynne Schrum, who has written three books on the topic of schools and technology. "Manipulating those are a little bit more difficult. Now there are virtual manipulative sites where students can play with the idea of numbers and what numbers mean, and if I change values and I move things around, what happens." 4. Probes and Sensors Collecting real-time data through probes and sensors has a wide range of educational applications. Students can compute dew point with a temperature sensor, test pH with a pH probe, observe the effect of pH on an MnO3 reduction with a light probe, or note the chemical changes in photosynthesis using pH and nitrate sensors. 5. More Efficient Assessment Models and simulations, beyond being a powerful tool for teaching concepts, can also give teachers a much richer picture of how students understand them. "You can ask students questions, and multiple choice questions do a good job of assessing how well students have picked up vocabulary," Dorsey explains. "But the fact that you can describe the definition [of] a chromosome ... doesn’t mean that you understand genetics any better ... it might mean that you know how to learn a definition. But how do we understand how well you know a concept?" Technology can help teachers collect real-time assessment data from their students. When the teacher gives out an assignment, she can watch how far along students are, how much time each spends on each question, and whether their answers are correct. With this information, she can decide what concepts students are struggling with and can pull up examples of students' work on a projector for discussion. 6. Storytelling and Multimedia Asking children to learn through multimedia projects is not only an excellent form of project-based learning that teaches teamwork, but it's also a good way to motivate students who are excited to create something that their peers will see. In addition, it makes sense to incorporate a component of technology that has become so integral to the world outside of the classroom. 7. E-books Despite students' apparent preference for paper textbooks, proponents like Daytona College and California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger are ready to switch to digital. And electronic textbook vendors like CourseSmart are launching to help them. 8. Epistemic Games Epistemic games put students in roles like city planner, journalist, or engineer and ask them to solve real-world problems. The Epistemic Games Group has provided several examples of how immersing students in the adult world through commercial game-like simulations can help students learn important concepts. In one game, students are cast as high-powered negotiators who need to decide the fate of a real medical controversy. In another, they must become graphical artists in order to create an exhibit of mathematical art in the style of M.C. Escher. Urban Science, the game featured in the above video, assigns students the task of redesigning Madison, Wisconsin. These eight technologies are redefining education. Which technologies would you add to the list? Let us know in the comments below. Series Supported by Dell The Power To Do More The Education Tech Series is supported by Dell The Power To Do More, where you'll find perspectives, trends and stories that inspire Dell to create technology solutions that work harder for its customers so they can do and achieve more. Text #2: We Live in a Mobile World Will Richardson, the co-founder of "Powerful Learning Practice," is the author of several books, including, "Personal Learning Networks: Using the Power of Connections to Transform Education." He is on Twitter as @willrich45. January 4, 2012, 4:37 PM, New York Times Let’s face it: For my children and for millions like them, life will be an open phone test. They are among the first generation who will carry access to the sum of human knowledge and literally billions of potential teachers in their pockets. They will use that access on a daily basis to connect, create and, most important, to learn in ways that most of us can scarcely imagine. Given that reality, shouldn’t we be teaching our students how to use mobile devices well? The analog, 20th century curriculum that most classrooms deliver doesn’t fit well with the realities of the exploding mobile, digital world. Right now, schools are resistant, fearing the disruption that mobile access might cause and the dangers that might lurk online. However, the analog, 20th century curriculum that most classrooms deliver doesn’t fit well with the realities of the exploding mobile, digital world. Our kids are stuck in a paper-based, local-learning system that doesn’t acknowledge the global, networked, always-on opportunities that mobile access affords. There's no doubt that the current slate of mobile devices have their limitations. There are still better technology options for constructivist, meaningful learning (i.e., laptops) that provide power and flexibility that phones and tablets cannot. That, of course, may change. But regardless, for many kids right now, especially at the lower end of the income scale, these devices are their only connections to the content and people who can help them learn great things. We need to leverage that. Access in our kids’ pockets will force us to rethink much of what we do in schools. For one thing, we have to stop asking questions in classrooms that students can now answer with their phones (state capitals anyone?) and instead ask questions that require more than just a connection to answer -- questions that call upon them to employ synthesis and critical thinking and creativity, not just memorization. Anything less is not preparing them for the information rich world that we live in. Notes on my thoughts, reactions and questions as I read: DO NOT TURN PAGE UNTIL INSTRUCTED TO DO SO AFTER THE VIDEO. Text #3 A Misguided Use of Money Paul Thomas, a public high school English teacher for 18 years, is an associate professor of education at Furman University in Greenville, S.C. You can follow his work at Radical Scholarship and on Twitter at @plthomasEdD. JANUARY 3, 2012 Reforming education in the U.S. often includes seeking new technology to improve teaching and learning. Instead of buying the latest gadgets, however, our schools would do better to provide students with critical technological awareness, achievable at little cost. Chalk board, marker board and now 'smart' board have not improved teaching or learning, but have created increased costs for schools. We rarely consider the negative implications for acquiring the newest “smart” board or providing tablets for every student. We tend to chase the next new technology without evaluating learning needs or how gadgets uniquely address those needs. Ironically, we buy into the consumerism inherent in technology (Gadget 2.0 pales against Gadget 3.0) without taking full account of the tremendous financial investments diverted to technology. Technology is a tool to assist learning. School closets and storage facilities across the U.S., though, are filled with cables, monitors and hardware costing millions of dollars that are now useless. Notably, consider one artifact that's covered in dust -- the Laserdisc video player (soon to be joined by interactive “smart” boards). Chalk board, marker board and now “smart” board have not improved teaching or learning, but have created increased costs for schools and profits for manufacturers. There is little existing research that shows positive outcomes from technology. Onestudy found that "most of the schools that have integrated laptops and other digital tools into learning are not maximizing the use of those devices in ways that best make use of their potential.” Notes on my thoughts, reactions and questions as I read: Reading a young adult novel on a Kindle or an iPad, or in paperback form, proves irrelevant if children do not want to read or struggle to comprehend the text. Good teachers, however, can make the text come alive for the children whether it's on a glowing screen or a piece of paper. Schools should not be blinded by the latest trends and the inflated costs of new technologies. Rather, we should empower teachers and divert resources into their classrooms in more meaningful ways. We’d do well to heed Henry David Thoreau: “We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate.” Join Room for Debate on Facebook and follow updates ontwitter.com/roomfordebate. Text #4: A Silicon Valley School That Doesn’t Compute By MATT RICHTEL, New York Times, October 22, 2011 LOS ALTOS, Calif. — The chief technology officer of eBay sends his children to a nineclassroom school here. So do employees of Silicon Valley giants like Google, Apple, Yahoo and Hewlett-Packard. But the school’s chief teaching tools are anything but high-tech: pens and paper, knitting needles and, occasionally, mud. Not a computer to be found. No screens at all. They are not allowed in the classroom, and the school even frowns on their use at home. Schools nationwide have rushed to supply their classrooms with computers, and many policy makers say it is foolish to do otherwise. But the contrarian point of view can be found at the epicenter of the tech economy, where some parents and educators have a message: computers and schools don’t mix. This is the Waldorf School of the Peninsula, one of around 160 Waldorf schools in the country that subscribe to a teaching philosophy focused on physical activity and learning through creative, hands-on tasks. Those who endorse this approach say computers inhibit creative thinking, movement, human interaction and attention spans. The Waldorf method is nearly a century old, but its foothold here among the digerati puts into sharp relief an intensifying debate about the role of computers in education. “I fundamentally reject the notion you need technology aids in grammar school,” said Alan Eagle, 50, whose daughter, Andie, is one of the 196 children at the Waldorf elementary school; his son William, 13, is at the nearby middle school. “The idea that an app on an iPad can better teach my kids to read or do arithmetic, that’s ridiculous.” Mr. Eagle knows a bit about technology. He holds a computer science degree from Dartmouth and works in executive communications at Google, where he has written speeches for the chairman, Eric E. Schmidt. He uses an iPad and a smartphone. But he says his daughter, a fifth grader, “doesn’t know how to use Google,” and his son is just learning. (Starting in eighth grade, the school endorses the limited use of gadgets.) Three-quarters of the students here have parents with a strong high-tech connection. Mr. Eagle, like other parents, sees no contradiction. Technology, he says, has its time and Notes on my thoughts, reactions and questions as I read: place: “If I worked at Miramax and made good, artsy, rated R movies, I wouldn’t want my kids to see them until they were 17.” While other schools in the region brag about their wired classrooms, the Waldorf school embraces a simple, retro look — blackboards with colorful chalk, bookshelves with encyclopedias, wooden desks filled with workbooks and No. 2 pencils. On a recent Tuesday, Andie Eagle and her fifth-grade classmates refreshed their knitting skills, crisscrossing wooden needles around balls of yarn, making fabric swatches. It’s an activity the school says helps develop problem-solving, patterning, math skills and coordination. The long-term goal: make socks. Down the hall, a teacher drilled third-graders on multiplication by asking them to pretend to turn their bodies into lightning bolts. She asked them a math problem — four times five — and, in unison, they shouted “20” and zapped their fingers at the number on the blackboard. A roomful of human calculators. In second grade, students standing in a circle learned language skills by repeating verses after the teacher, while simultaneously playing catch with bean bags. It’s an exercise aimed at synchronizing body and brain. Here, as in other classes, the day can start with a recitation or verse about God that reflects a nondenominational emphasis on the divine. Andie’s teacher, Cathy Waheed, who is a former computer engineer, tries to make learning both irresistible and highly tactile. Last year she taught fractions by having the children cut up food — apples, quesadillas, cake — into quarters, halves and sixteenths. “For three weeks, we ate our way through fractions,” she said. “When I made enough fractional pieces of cake to feed everyone, do you think I had their attention?” Some education experts say that the push to equip classrooms with computers is unwarranted because studies do not clearly show that this leads to better test scores or other measurable gains. Is learning through cake fractions and knitting any better? The Waldorf advocates make it tough to compare, partly because as private schools they administer no standardized tests in elementary grades. And they would be the first to admit that their early-grade students may not score well on such tests because, they say, they don’t drill them on a standardized math and reading curriculum. When asked for evidence of the schools’ effectiveness, the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America points to research by an affiliated group showing that 94 percent of students graduating from Waldorf high schools in the United States between 1994 and 2004 attended college, with many heading to prestigious institutions like Oberlin, Berkeley and Vassar. Of course, that figure may not be surprising, given that these are students from families that value education highly enough to seek out a selective private school, and usually have the means to pay for it. And it is difficult to separate the effects of the low-tech instructional methods from other factors. For example, parents of students at the Los Altos school say it attracts great teachers who go through extensive training in the Waldorf approach, creating a strong sense of mission that can be lacking in other schools. Absent clear evidence, the debate comes down to subjectivity, parental choice and a difference of opinion over a single world: engagement. Advocates for equipping schools with technology say computers can hold students’ attention and, in fact, that young people who have been weaned on electronic devices will not tune in without them. Ann Flynn, director of education technology for the National School Boards Association, which represents school boards nationwide, said computers were essential. “If schools have access to the tools and can afford them, but are not using the tools, they are cheating our children,” Ms. Flynn said. Paul Thomas, a former teacher and an associate professor of education at Furman University, who has written 12 books about public educational methods, disagreed, saying that “a spare approach to technology in the classroom will always benefit learning.” “Teaching is a human experience,” he said. “Technology is a distraction when we need literacy, numeracy and critical thinking.” And Waldorf parents argue that real engagement comes from great teachers with interesting lesson plans. “Engagement is about human contact, the contact with the teacher, the contact with their peers,” said Pierre Laurent, 50, who works at a high-tech start-up and formerly worked at Intel and Microsoft. He has three children in Waldorf schools, which so impressed the family that his wife, Monica, joined one as a teacher in 2006. And where advocates for stocking classrooms with technology say children need computer time to compete in the modern world, Waldorf parents counter: what’s the rush, given how easy it is to pick up those skills? “It’s supereasy. It’s like learning to use toothpaste,” Mr. Eagle said. “At Google and all these places, we make technology as brain-dead easy to use as possible. There’s no reason why kids can’t figure it out when they get older.” PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK FOR PLANNING AND NOTES FOR THE ESSAY IN PART TWO PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK FOR PLANNING AND NOTES FOR THE ESSAY IN PART TWO