Themes List

Themes:

Pride John does not want to sign the confession because he would loose his pride and good name.

Revenge The girls and the accusers were naming people whom they did not like and wanted to harm them.

Fear - Fear of the devil allowed the witch trials to go on.

Conflict of authority - Danforth felt the law should be followed exactly, and that anyone who opposed the trials was trying to undermine him and his authority and the church.

Puritan Ethics - They believed lying and adultery were horrible sins.

Self interest - They were looking out for their own lives and took whatever actions necessary to save themselves.

Honesty - Elizabeth was "not able to tell a lie".

Key issues:

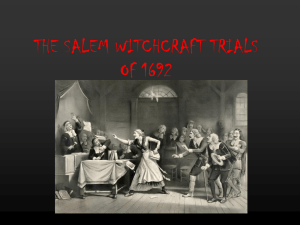

Fear, self interest: Shows what happens when emotions control your logic and thinking. Hysteria will occur. Shows how people will accuse others in order to save themselves. This leads to a wild finger pointing. Also when you were accused of being a witch, in order to save yourself you could accuse other women. People in the town allowed their fear of witches and the devil to interfere with their rational thinking.

Puritan Ethics: The church was very important in their daily life. The Puritans were very religious. They were scared of modern things destroying the old church. They believed in the devil and that you could make pacts with him. It was a horrible sin to lie.

Integrity: John had to deal with the fact that he had an affair with Abigail and broke the trust between Elizabeth and him. He sinned, and the people of the town would have condemned him, if they knew.

Lessons/morals/applications:

Honesty: Elizabeth cannot tell a lie says John Proctor, but she will lie to protect

John. In some cases you have to lie. Hale agrees with this. He says "God damns a liar less than he that throws his life away for pride."

Applications: The McCarthy trials. This story relates to these trials. During the

1950's Senator Joseph Mc Carthy accused many American leaders of being communists. This lead to many unfounded accusations that people were communists. Some people believed him because they were fearful of communism and he played on their fears. McCarthy was, in effect, conducting

"witch hunts". If you opposed the Salem Witch trials you were accused of being a witch. If you opposed the Mc Carthy investigations you were accused of being a communist.

WITCHCRAFT IN 16TH AND 17TH CENTURY ENGLAND

James I was king of England (1603-1625) when the Pilgrims set sail for Northern

Virginia (New England) in 1620. James I was a firm believer in witches and witchcraft and the harm they could do. He even wrote an authoritative account of witchcraft entitled Daemonologie. His belief in witchcraft probably inspired

William Shakespeare to prominently feature witches in Macbeth, a play widely believed to be an homage to James I and his supposed ancestor Banquo ("Thou shalt get kings though thou be none").

This passage from Witches and Jesuits: Shakespeare's Macbeth by Garry Wills helps us imagine the climate of the times in the late 16th and early 17th century in England:

Witchcraft was not just a matter of private concern, filling the law courts with complaints of hexes and love spells. It was a factor in affairs of state. Elizabeth's government showed enough concern when a crude image of herself was discovered that it called in John Dee, the master of occult lore, to prescribe protective measures. This baffled plot against Elizabeth was described by Dekker in The

Whore of Babylon, where a conjurer offers his service against the Queen (2.2.168-175):

This virgin wax Bury I will in slimy-putrid ground, Where it may piecemeal rot. As this consumes, So shall she pine, and (after

languor) die. These pins shall stick like daggers to her heart And, eating through her breast, turn there to gripings, Cramplike convulsions, shrinking up her nerves As into this they eat.

This is the "pining" spell witches were known for, the one

Shakespeare's witch casts on a sailor (1.3.22-23):

Weary sev'n-nights, nine times nine, Shall he dwindle, peak, and pine.

King James discussed such magic use of images in his dialogue.

Elizabeth was also attacked with hellish potions, including the magic poison smeared on her saddle pommel by Edward Squire.

King James was even more plagued by political witchcraft than was

Elizabeth. Most of the major conspiracies against his life involved witchcraft. In 1590 Dr. Fian used a "school" of witches to cast spells on him. In 1593 Bothwell's rebellion led to an indictment for witchcraft. In 1600, when the Gowrie Plot failed, magic formulas were found on the body of the man who tried to assassinate the

King. It is not surprising that the King should dwell on the dark arts that abetted the Powder Plotters-this was just a new piece in the old pattern of James's psychomachia with hellish powers. (Wills,

Garry, Witches and Jesuits: Shakespeare's Macbeth, Oxford

University Press, 1995, pages 41-42.)

This was the climate of the times when the Puritans settled New

England. Witches and witchcraft were often blamed for unknown phenomena, and deeply religious people like the Puritans were especially prone to see the devil's hand in unpleasant circumstances.

The wilderness of the New World presented a particularly potent set of unknown circumstances and dangers. Perhaps it is not surprising that the hysteria of Salem was the result.

For a comprehensive listing of books on the subject, consult the Bibliography on

Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and America

( http://www.hist.unt.edu/witch01.htm

).