Complete Unit.doc

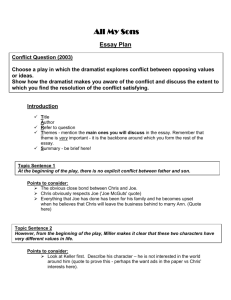

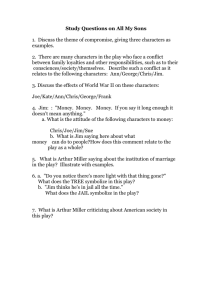

advertisement

Arthur Miller Miller was born in New York in 1915. He left high school in the 1930s but was unable to continue studying at university because of the depression at the time. He saved enough money, by working in a warehouse, to go to university in Michigan for one term only. Later, by working in a newspaper and gaining prizes for play writing, he was able to complete his studies at Michigan. He was married 3 times, the 2 nd time being to Marilyn Monroe. His plays include ‘All My Sons’ (1947), ‘Death of a Salesman’ (1949), ‘The Crucible’ (1953), ‘The Price’ (1968), ‘The Crash’ (2003) and he wrote the film script for ‘The Misfits’ (1961) the last film in which Marilyn Monroe starred. Miller used the techniques of the modern theatre to the full. He did not only make use of lighting and sound, but indicated precisely when a particular form of lighting or sound was to be used. This was an attempt to make the whole theatre, not simply the actors, express the message of the play. Mechanical devices, therefore, have a symbolic significance and represent an essential meaning or idea in the play. They express meaning, therefore the term EXPRESSIONIST is often used to describe Miller as a dramatist. Miller was writing for a middle-class audience, therefore his plays reached only a small proportion of the population. He used this fact to his advantage in All My Sons where he examined American middle-class ideas and beliefs. He was able to place before his audience Joe Keller, a man who shared many of their ideals, ones which have been summed up by the phrase ‘The American Dream’. This dream is a combination of beliefs in the unity of the family, the healthiness of competition in society, the need for money and success and the view that America is the great land in which free opportunity for all exists. Miller used this belief to state something significant about American society and the flaws he saw in the ‘dream’. He was both a social and a psychological dramatist. As a social dramatist he commented on the nature of society. He was concerned about society and its values and because of this he was regarded as an ally of the ‘left’; someone who wanted to challenge the values of society and show them as worthless. His plays suggested change was necessary. As a psychological dramatist he studied the character and the motives and reasons for the behaviour of individuals and he presented them so that characters became convincingly alive. Often characters were ordinary citizens, leading a life that was not obviously interesting. Nevertheless, Miller could point out the important, the interesting and the unusual in their lives and the audience could therefore identity with the situation and the psychological state of the characters. Miller was able to show that everyday people can rise above the ordinary when challenged. All My Sons All My Sons is a powerful story about family loyalty, corporate responsibility, love, betrayal and society. It is set in a small American town, post WWII. Joe Keller runs a successful industrial manufacturing company that provided parts for the air force while his own sons were serving in the war. One of the sons goes missing, and his mother Kate desperately needs to believe that her missing son is returning one day. Chris, who came back from the war, is ready to head-up the family business and wishes to propose to Ann, the sweetheart of his missing brother, whom he has invited to visit the family home. The set takes you right into the world of the Kellers, built as it is around the destruction of a peaceful facade. Neighbours share a peaceful moment reading the morning newspaper while there is debris and a broken apple tree on the lawn from the storm the night before. The music creates an atmosphere of somehow ominous calm, and the lighting effectively changes the tone of each scene. The set is meticulously crafted, and there is nothing here without purpose: you even strain to see the photographs behind the screen door. This is a play about universal themes: “Once and for all you must know that there’s a universe of people outside, and you’re responsible to it.” It’s relevant today after the recent Iraq war: do we put our family first, our country first, or the world? Who are we fighting for? This is an intense play. Introduction The action of the play is set in August 1947, in the mid-west of the U.S.A. The events depicted occur between Sunday morning and a little after two o'clock the following morning. Joe Keller, the chief character, is a man who loves his family above all else, and has sacrificed everything, including his honour, in his struggle to make the family prosperous. He is now sixty-one. He has lost one son in the war, and is keen to see his remaining son, Chris, marry. Chris wishes to marry Ann, the former fiancée of his brother, Larry. Their mother, Kate, believes Larry still to be alive. It is this belief which has enabled her, for three and a half years, to support Joe by concealing her knowledge of a dreadful crime he has committed. Arthur Miller, the playwright, found the idea for Joe's crime in a true story, which occurred during the second world war: a manufacturer knowingly shipped out defective parts for tanks. These had suffered mechanical failures which had led to the deaths of many soldiers. The fault was discovered, and the manufacturer convicted. In All My Sons, Miller examines the morality of the man who places his narrow responsibility to his immediate family above his wider responsibility to the men who rely on the integrity of his work. Background to the action Three and a half years before the events of the play, Larry Keller was reported missing in action, while flying a mission off the coast of China. His father, Joe Keller, was head of a business which made aero engine parts. When, one night, the production line began to turn out cracked cylinder heads, the night foreman alerted Joe's deputy manager, Steve Deever as he arrived at work. Steve telephoned Joe at home, to ask what to do. Worried by the lost production and not seeing the consequences of his decision, Joe told Steve to weld over the cracks. He said that he would take responsibility for this, but could not come in to work, as he had influenza. Several weeks later twenty-one aeroplanes crashed on the same day, killing the pilots. Investigation revealed the fault in the cylinder heads, and Steve and Joe were arrested and convicted. On appeal, Joe denied Steve's (true) version of events, convinced the court he knew nothing of what had happened, and was released from prison. Before his last flight, Larry wrote to his fiancée, Ann, Steve's daughter. He had read of his father's and Steve's arrest. Now he was planning suicide. Three and a half years later, Ann has told no-one of this letter. Kate Keller knows her husband to be guilty of the deaths of the pilots and has convinced herself that Larry is alive. She will not believe him dead, as this involves the further belief that Joe has caused his own son's death, an intolerable thought. She expects Larry to return, and keeps his room exactly as it was when he left home. She supports Joe's deception. In return she demands his support for her hope that Larry will come back. Ann and her brother, George, have disowned their father, believing him guilty. But George has gone at last to visit his father in jail, and Steve has persuaded him of the true course of events. The play opens on the following (Sunday) morning; by sheer coincidence, Ann has come to visit the Kellers. For two years, Larry's brother, Chris, has written to her. Now he intends to propose to her, hence the invitation. She is in love with him and has guessed his intention. On the Saturday night there is a storm; a tree, planted as a memorial to Larry, is snapped by the wind. Kate wakes from a dream of Larry and, in the small hours, enters the garden to find the tree broken. Brief Character Outlines Joe Keller is not a very bad man. He loves his family but does not see the universal human "family" which has a higher claim on his duty. He may think he has got away with his crime, but is troubled by the thought of it. He relies on his wife, Kate, not to betray his guilt. Chris Keller has been changed by his experience of war, where he has seen men laying down their lives for their friends. He is angry that the world has not been changed, that the selflessness of his fellow soldiers counts for nothing. He feels guilty to make money out of a business which does not value the men on whose labour it relies. Kate Keller is a woman of enormous maternal love, which extends to her neighbours' children, notably George. Despite her instinctive warmth, she is capable of supporting Joe in his deceit. To believe Larry is dead would (for her) be to believe his death was a punishment of Joe's crime (an intolerable thought), so she must persuade herself that Larry still lives. Joe sees this idea to be ridiculous, but must tolerate it to secure Kate's support for his own deception. Ann Deever shares Chris's high ideals but believes he should not feel ashamed by his wealth. She disowns her father whom she believes to be guilty. She has no wish to hurt Kate but will show her Larry's letter if she (Kate) remains opposed to Ann's marrying Chris. Dr. Jim Bayliss is a man who, in his youth, shared Chris's ideals, but has been forced to compromise to pay the bills. He is fair to his wife, but she knows how frustrated Jim feels. Jim's is the voice of disillusioned experience. If any character speaks for the playwright (Arthur Miller), it is Jim. Sue Bayliss is an utterly cynical woman. Believing Joe has “pulled a fast one”, she does not mind his awful crime, yet she dislikes Chris because his idealism, which she calls “phoney”, makes Jim feel restless. She is an embittered, rather grasping woman, whose ambitions are material wealth and social acceptance. She does not at all understand the moral values which her husband shares with Chris. George Deever is a soul-mate of Chris. When younger, he greatly admired him. In the war, like Chris, he has been decorated for bravery. He follows Chris in accepting that Steve is guilty. Now he reproaches Chris for (as he sees it) deceiving him. He is bitter because he has grown cynical about the ideals for which he sacrificed his own opportunities for happiness. Lydia Lubey is a rather one-dimensional character: she is chiefly in the play to show what George and Chris (so far) have gone without. She is simple, warm and affectionate, rather a stereotype of femininity (she is confused by electrical appliances). Her meeting with George is painful to observe: she has the happy home life which he has forfeited. We understand why George declines her well-meant but tactless invitation to see her babies. Frank Lubey (unlike George, Larry, Chris and Jim) is a materialist. He lacks culture, education and real intelligence, but has made money in business, and has courted Lydia while the slightly younger men were fighting in the war. His dabbling in quack astrology (horoscopes) lends support to Kate's wild belief that Larry is still alive. Plot Overview Act 1 Sunday morning – August any year – 3 years after a war – Keller home – one day in the lives of the Keller family. Tree planted for Larry blown down (in its prime) – Anne has arrived – invited by Chris – he intends to propose – Joe afraid of Kate’s reaction to this marriage – already in a nervous state – description of Larry flying over house – Chris proposes – Anne accepts – Chris’ story of the war – wedding to be announced after dinner – Joe tells his story of what happened in the factory – Kate insists Anne is still Larry’s girl – Anne’s brother phones – coming to visit – been to visit father in jail – Joe worried – a trap? Act 2 Family dressed for dinner – Jim gone to collect George – Sue tells Anne neighbours know Joe is guilty – Anne shocked – George arrives – wants Anne to leave with him – Kellers cannot have her too – believes father ‘innocent’ now – only believed Joe because Chris did – calmed down by Kate – ready to leave alone – Kate makes the slip – Joe admits his part in the crime – did it for Chris – Chris walks out. Act 3 Chris has been gone for some time – Jim goes to look for him – Anne been in Larry’s room since Joe’s admission – Kate wants Joe to say he’ll go to prison – Chris will not let him, but it would make Chris feel better – Anne presents her compromise – let her marry Chris (pronounce Larry dead) she’ll go away with him – say nothing – Kate refuses – Joe goes inside – Anne shows Kate Larry’s suicide letter – Chris returns – his compromise – go away alone – say nothing – Anne asks Kate to tell him Larry is dead – she will not – Anne goes to show him the letter – Joe returns – Joe confronts Chris – Chris cannot look at himself or Joe because of the association with this crime – Anne shows letter to Chris – Larry killed himself because of the news stories about Joe – no more compromises – Joe must go to the authorities – Chris prepares to take him – Joe goes to get jacket – shoots himself. Tension Graph High Med Low Act & Scene Analysis Act I The important events in All My Sons have already transpired. The only action that occurs within the time frame of the narrative is the revelation of certain facts about the past, and it is important to track how the revelations change the relationships among the characters as well as their own self-definition. Arthur Miller carefully controls the flow of information rather than focusing on plot and action. Thus the play, influenced by the work of the playwright Ibsen, is paced by the slow revelation of facts. In the first act, not much is said that is unknown to the characters, but it is all new to the audience. Miller takes his time revealing the background information to the audience by having the characters obliquely refer to Larry and to his disappearance again and again, until all the necessary information has been revealed through natural dialog. The explanation of Keller's and Steve's business during the war, and the ensuing scandal, is similarly revealed through insinuation and association. The first reference to Steve's incarceration occurs when Ann says that her mother and father will probably live together again "when he gets out." This does not mean much to the audience until Frank asks about Steve's parole. Therefore, Ann's estrangement from her father and the community's hostility and curiosity towards the man are established before the audience knows exactly where Steve is and how he got there. Miller's manipulation of the background information heightens the anticipation and the curiosity of the audience. Again, very little new information is presented to the characters in this act. Chris reveals his intentions to marry Ann to his father, Ann learns of Chris's feelings of guilt for surviving the war and coming home to a successful business, and Mother learns that Ann has not exactly been waiting for Larry all these years. Yet Miller's skilful and carefully planned withholding of the characters' backgrounds prevents the first act from feeling like forty minutes of exposition--which, in function, it actually is. The slow pace of the first act also allows the horror of the crime to seep into the atmosphere, imbuing the audience with a sense that this idyllic, placid community has been injected with a slow poison. In addition, as in many plays and written works, Miller's choices in establishing the relationships in this fashion allow him to closely manipulate the audience's inferences and judgments about each character. (The effect is not unlike that of F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby, in which the firstperson narrator, speaking after the events of the narrative, slowly reveals Daisy Buchanan's character to the reader.) Yet Arthur Miller did not have the narrative tools of the novel at his disposal like Fitzgerald did. A playwright mainly employs dialogue. Therefore, readers and viewers should pay careful attention to the ways that Miller sets up the necessary details about each character and their relationships. Keller's insistence that Steve was not a murderer, and Chris's strong belief that patching those cracked airplane heads was morally reprehensible, are not just foreshadowing. They are essential elements of each character's personal trajectory, and these elements express the principal concept of the play: the past has an enduring influence on the present which never quite goes away. Fitzgerald's work leaves the reader with the message that one "can't repeat the past," and Miller's adds the caveat that one cannot ignore the past either. The first act also illustrates the tensions between the characters that will rise to the surface in the second and third acts. The Kellers seem like a happy family at first; it is even remarked that Chris is the rare sort of person who truly loves his parents. But there is resentment beneath the surface of their contented existence, resentment that reflects more than just grief at the loss of a son. Larry was clearly the favoured of the Keller boys. Keller compares Larry's business sense to Chris's lack of it, and Chris complains that he has always played second fiddle to Larry in the eyes of his parents and of Ann, who was first betrothed to Larry. The family sometimes implies bitterness that Chris, not Larry, was the son who survived the war. Chris is too idealistic, too soft about business. Like Michael Corleone in Mario Puzo's The Godfather, Chris returned from the war with a new idealism that will not permit him to condone his father's shadier business practices. And like Vito Corleone, Keller believes that his actions are legitimate if he acts for the sake of his family. In the end, like Michael Corleone, Chris must compromise his values in order to protect his father and his own family. Mother's insecurities are expressed through her obsessive delusions about her dead son. She is anxious, suspicious of Ann, and highly superstitious. She cannot handle her husband's casual "jail" game with the neighborhood children, because there is something weighing on her conscience. Jail has been a real spectre in this family. When Keller responds to her worries with "what have I got to hide?" we see the first clue that he does have something to hide after all--and Mother knows all about it-and it makes her sick with worry. Ann is more of a simple character, serving the purpose of the plot but not actually a focus of the plot herself. All My Sons is the story of the Kellers, so we do not see much of Ann's reaction to the realisation that her father was largely innocent after all. She functions in this act as a catalyst, a femme fatale in the literal sense, the woman who brings destruction to the false calm of the Kellers' life by churning up a past that some of the family, in some ways, has tried to ignore. She and George have their own family drama, but Miller keeps a tight focus, so Ann's and George's story is not the subject of this play except in as much as their disgust for their father heightens the tension between another son and a father who might be guilty. Notes Analysis Act II Much of Miller's drama focuses on the unexceptional man. His Death of a Salesman is a fanfare for the common man, putting the dreary plights and small ambitions of the lower middle class into the anti-hero of Willy Loman. Miller finds high drama in the life of a man so common that he could be anyone in the audience, and that is why Death of a Salesman continues to resound so strongly with audiences, especially men of a certain age. Likewise, in The Crucible Miller takes commonplace people and puts them in the extraordinary situation of the Salem witch trials. The drama of the everyman is a trope throughout Miller's oeuvre, and it begins to surface as well in All My Sons, his first prominent play. The theme is first made apparent when Keller tries to justify Steve's actions during the war. He calls Steve a "little man," who buckled under pressure from the military when a shipment of cracked cylinder heads came through his inspection. Keller draws a distinction between men who are easily pressured and are natural followers (Steve) and men who can stand up for themselves and make the difficult choice in a bad situation (himself). The irony, of course, is that he is defending Steve a little too vehemently, because only he and his wife know that Keller actually belongs in the former category of the common follower. Keller may talk big, but we learn at the end of the second act that when the military was on the phone and he had to make a decision; Keller was the one who caved in to circumstance. The little man whom the hero patronizingly defends at the beginning of the play turns out to be rather like the hero himself. Despite Keller's insistence that he was thinking of his family in the choice, it seems more likely that his first thought was on keeping his business. This emphasis, if true, reflects poorly not just on Keller but on the profit orientation of the capitalism within which he acts. Wartime racketeering and the merciless pursuit of business profit to the exclusion of human decency are, in Miller's worldview, part and parcel of the American capitalist system. Miller's leftist sympathies are no secret; the witch hunts of The Crucible are a thinly veiled allegory of the show trials of the McCarthy era, and Death of a Salesman is a virulent attack on a society that uses a man up during his working years and then leaves him out to dry when he is no longer useful. All My Sons was first produced before Miller's fame gave him the ability to launch more direct assaults on the ways that the profit-seeking elements of capitalism can tend to destroy American social structure, but the implicit critique is still salient here. Keller is not presented as a villain but as an ordinary man caught up in a bad situation and who makes a choice according to his own values. Indeed, if Keller really was thinking of his family, it would have been hard for him, in the Weberian, steel-hard shell of capitalist culture, to make a different choice. He might have lost the business and landed his family in poverty after all. Through Chris, nevertheless, Miller challenges Keller's individual or family values as misguided, ignorant, and destructive in relation to the larger social and cultural values he could have been paying attention to. Even so, everyone intends to act in view of what one thinks is the good. Like Willy Loman, Keller is a tragic antihero, a relic from a simpler time before higher education and professionalization were widespread, when the nuclear family was truly the nucleus of a man's world and his community did not seem to extend to the whole world. Keller sees himself and his business as just one small cog in the American war machine, which is part of a world far beyond himself and his real influence. What he does not understand is that the actions of this small cog do have implications far wider than what he can see with his own eyes. He is answerable not to his family, but to his society. The issue is how to balance the competing claims of self, family, and society. Is it really acceptable to cause twenty-one people to die? His society thinks not, which is why Keller's associate was put in jail. Moreover, Keller prefers to see himself as a victim of others. Instead of dealing with his complicity in a scandal that sent pilots to their deaths, Keller denies his involvement and passes off the blame, protecting his self-image and preserving the illusion that he has legitimately maintained his rightful place in society. When George opens up the old accusations, Keller is ready for him with a list of incidents in which George's father endangered the business. He is blind to the impulses within himself that make him just as dangerous as his meek and unassuming former partner, preferring to think of himself as a man among men, minding his own business (literally and figuratively). That is the true flaw in Keller's character; though he may not be fully faulted for imprecisely calibrating the complex values involved in his life, he denies the responsibility that he knows he should own up to. His denial, which keeps him out of jail, is paradoxically what ends up eating through his family's tranquillity and locking him in his own self-imprisonment of shame and deception. And when the truth is finally revealed, at first through his wife's slip of the tongue, Keller tries to mitigate his guilt by portraying himself as the victim once more, dealing with forces outside his control. Whereas before he belittled Steve for caving under the pressure, now he claims that the very same actions were the only sensible, businesslike things to do. He rationalizes that he was just serving the principles of good business, and that he thought the parts would hold up just fine in the air. But when Chris forces him to admit that he had his doubts about the planes' safety, he again justifies his decision by claiming that he was just one of thousands of men on the wartime profiteering bandwagon. "Who worked for nothin' in that war?" he asks. Yet his denials and deflections of blame, rather than assuaging his son, lead to Chris's complete disillusionment in the moral fibre of his father. (See Centola, 1997, on this topic.) The dialogue in the second act varies between long, explanatory speeches, and fast exchanges characterized by extensive questioning. As the tension mounts, the questions grow shorter and more rapid-fire, increasing the pressure on Keller line by line. At the climax, the staccato dialogue heightens the drama of the courtroom-like confrontation between father and son. The stage directions indicate that "their movements now are those of subtle pursuit and escape." Where first Chris was asking questions about what happened and Keller was explaining, now Chris is hurling accusations and Keller is answering in defensive questions: "Dad, you killed twenty-one men!" "What, killed?" They are replaying the ancient dance of the archetypal father-son conflict. The act finishes with Chris's speech, building through eight questions, until he asks finally, "Don't you live in the world?" He then pulls back from that peak by redirecting the last question to himself, confessing that he does not know what to do. A son may find his father guilty, but how can he punish him? (See Griffin, 1996.) Notes Analysis Act III Like her husband, Mother is in denial. She knows about Keller's guilt, and it is the source of her anxiety and headaches throughout the play. She is complicit in Keller's denial, and as for her own denial, she is forcing her son to stay alive, if only in her mind, in order to allow her to continue to live with her husband in some acceptable way. That is, if she had to accept that her husband effectively killed their son, then she could not bear it. But her loyalty to Keller ironically serves to separate the couple, since her knowledge of his guilt strains their relationship. Like her husband, she prefers to believe that there are forces outside her control--in her case, astrology and God's choice, both on Larry's side--that ultimately dictate life or death more than individual choice does. But all this is not the blind trust of a grief-stricken mother. Just as she mistakenly thought that Chris always knew in the back of his mind that Keller was guilty, she always knew in her heart that Larry was dead, despite a play full of protestations to the contrary. When Ann shows her the letter that proves Larry's death, Mother suffers no great shock. Like Martha in Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, she learns the "death" of a son who did not really exist anymore anyway. She knew--she always knew. What mattered was that no one said it aloud, because that way she would not have to examine the implications. And again like Albee's Martha, what truly died was not the son, but the mother's selfdeception, the universe she had constructed inside her head in order to cope with the painful truth. The title of the play becomes clear in Keller's final line. After years of denial, he is forced to acknowledge that the soldiers who died as a direct result of his actions were someone's sons, and they all might as well have been his sons. But this line, with the title, actually serves two independent arguments that run through the work. "All My Sons" has both an emotional centre and an intellectual centre. The emotional "All My Sons" has the Keller family at its core, being primarily concerned with the impact of shameful secrets on family relationships, in particular how their past can come back to haunt the present. When the work is performed, audiences are usually struck the hardest by the story of the crime and its consequences for the Keller family. But the intellectual "All My Sons" is the story of that same crime and its consequences not for the Keller family, but for the world. If Miller is proposing a world-scale ethic of concern for everyone's sons, he proposes that Keller (and each member of the audience) should find in himself a kind of generalized care for all of the sons and daughters in the world. Miller later wrote that he wanted the play to be about "unrelatedness," describing Keller as a man who "cannot admit that he, personally, has any viable connection with his world, his universe, or his society." The admission that the pilots were "all my sons" is, for Keller, an admission that he might as well have killed his own child. The admission is also a new understanding that it should not matter whether the dead pilots could have been his sons; rather, we all have an obligation to society to value everyone's sons as though they were our own. Whether that level of concern is possible or feasible, indeed whether it is healthy and desirable to refuse to help your own children and neighbours while you try to help the whole world, is a different question, but the idealist might give it a try. The tension among these values is highlighted throughout the play in Keller's and Chris's conflicting moralities. For Keller, there is nothing more important in this world than the family. For Chris, the destruction of the war wrought a new "kind of--responsibility. Man for man." And in the play, Keller's morality actually eclipses Chris's, even though Miller is giving the audience a shot at accepting Chris's leftist argument. In the end, what draws audiences is the emotion of a comprehensible, identifiable unit of society--that is, the drama of the nuclear family. The primacy of Miller's unrelatedness argument is defeated by its own truth. We will always care more about the one son whose father we see before us and with whom we identify, than the twenty-one dead sons who are not our own. At least, however, we can rise to the responsibility of making wise and prudent decisions to honour both the one and the twenty-one as well as we can. Notes Themes Relatedness: Arthur Miller stated that the issue of relatedness is the main one in All My Sons. The play introduces questions that involve an individual's obligation to society, personal responsibility, and the distinction between private and public matters. Keller can live with his actions during the war because he sees himself as answerable only to himself and his family, not to society as a whole. Miller criticizes Keller's myopic worldview, which allows him to discount his crimes because they were done "for the family." The principal contention is that Keller is wrong in his claim that there is nothing greater than the family, since there is a whole world to which Keller is connected. To cut yourself off from your relationships with society at large is to invite tragedy of a nature both public (regarding the pilots) and private (regarding the suicides). The Nuclear Family: The reverse side of Miller's relatedness argument is his downplaying of the family as the nucleus of society. Somehow people are to feel a more general caring for others that is not drawn off by family obligations. What, then, is the place of the family in the larger social system? Discussions of the family serve mostly to contrast characters' opinions about an individual's responsibilities to the family versus society at large. The family is also presented as a unit that can be corrupted and damaged by the actions and denials of its individuals, a small-scale example of the way individual actions can corrupt society. The Past: All My Sons is a play about the past. It is inescapable--but how exactly does it affect the present and shape the future? Can crimes ever be ignored or forgotten? Most of the dialogue involves various characters discovering various secrets about the recent history of the Keller family. Miller shows how these past secrets have affected those who have kept them. The revelation of the secrets is presented as unavoidable--they were going to come out at some point, no matter what, and it is through Miller's manipulation of the catalysts that the truths are all revealed on the same day. Whilte the revelations are unavoidable, so are their fatal consequences. Denial and Self-Deception: How do we deceive ourselves and others? We select things to focus on in life, but do we also need to deny certain things in order to live well? What toll does denial take on the psyche, the family, and society? Two main facts about the Keller family history must be confronted. One is Larry's death, and the other is Keller's responsibility for the shipment of defective parts. Mother denies the first while accepting the second, and Keller accepts the first while denying the second. The result is that both characters live in a state of self-deception, wilfully ignoring one of the truths so that the family can continue to function in acceptable ways. Idealism: Chris is described by other characters as an idealist, although we do not see this trait in action aside from his angry response to the wartime profiteering. Yet the others define him by his idealism, setting him apart as a man of scruples. Chris decides that he must abandon these scruples to the cause of practicality when he is faced with the prospect of sending his father to jail. Is idealism sustainable in a fallen, complex world? If ideals must be sacrificed, is there any supervening ideal or principle to help us decide which ideals should be sacrificed in which circumstances? Business: Keller argues that his actions during the war were defensible ass requirements of good business practice. He also frequently defines himself as an uneducated man, taking pride in his commercial success without traditional book learning. Yet, his sound business sense actually leads to his downfall. This failure is connected with Miller's leftist politics and the play's overall criticisms (shared by some conservatives) of a capitalist system that encourages individuals to value their business sense over their moral sense. How could rules that govern business be exempt from the moral norms and laws governing the rest of society? Blame: Each character in the play has a different experience of blame. Joe Keller tries to blame anyone and everyone for crimes during the war, first by letting his partner go to jail. Later, when he is confronted with the truth, he blames business practice and the U.S. Army and everyone he can think of-except himself. When he finally does accept blame, after learning how Larry had taken the blame and shame on himself, Keller kills himself. Chris, meanwhile, feels guilty for surviving the war and for having money, but when the crimes are revealed, he places the blame squarely on his father's shoulders. He even blames his father for his own inability to send his father to prison. These are just a few examples of the many instances of deflected blame in this story, and this very human impulse is used to great effect by Miller to demonstrate the true relationships and power plays between characters as they try to maintain self-respect as well as personal and family honour. The American Dream: Miller points out the flaw with a merely economic interpretation of the American Dream as business success alone. Keller sacrifices other parts of the American Dream for simple economic success. Has he given up part of his basic human decency (consider the pilots) and a successful family life--does he sacrifice Steve or Larry? Miller suggests the flaws of a capitalist who has no grounding in cultural or social morals. While Keller accepted the idea that a good businessman like himself should patch over the flawed shipment, Miller critiques a system that would encourage profit and greed at the expense of human life and happiness. The challenge is to recover the full American Dream of healthy communities with thriving families, whether or not capitalism is the economic system that leads to this happy life. Economic mobility alone can be detrimental--consider George's abandonment of his hometown for big city success. There is a rift in the Bayliss marriage over Dr. Bayliss's desire to do unprofitable research, because his wife wants him to make more money instead of do what he enjoys and what will help others. Conflict This play is about conflict arising within the Keller family, and in particular within the character of Chris Keller. The conflict comes from the lack of principles show by people, particularly Joe Keller, with regard to war and the consequences of war. The play concentrates on 2 main problems arising from war: 1. people making money/profit from the deaths of others and 2. the absence of any real improvement in society as a result of a war (nothing is changed or made better by war or the sacrifice it demands of people). These problems are evident because of the effect they have on the character of Chris Keller – a man of high principles, who refuses to compromise in the way the rest of the world has. Conflict within Chris Chris is the elder brother; he is 32 years old. He is seen as having a great capacity for loyalty and affection and is seen as an example to others (others believe Joe’s lie about the factory because Chris believes Joe). He is similar to Joe in that he is not a man of great intelligence and he is a solid worker. Conflict within Chris arises because his loyalties are divided. He is loyal to his mother and feels he cannot hurt her, yet he wants to marry Ann – he knows to do so will hurt his mother. This would be like ‘killing’ Larry – an open admission to the world that Larry is dead and gone. His mother says she’ll kill herself if this is the case, because if she admits that Larry is dead, she must also admit Joe is guilty of killing the sons of 21 other mothers, who all wait in the night for their sons to return. If he does not marry Ann, he is disloyal to himself. He tells us he’s always done without for the sake of others – this time he is going to get what he wants. He is loyal to the men who served under him during the war. He saw them fight and die for one another and for their country. He believes they should have been heroes, but the country does not appreciate what they did – they could have died in a bus crash. Because of this lack of feeling from others, Chris’ feelings are all the stronger: he sees war as ‘dirty’. Those were great men, great friends who died, and for what? So all the money/profit from war is also ‘dirty’ and he wants nothing to do with it – this included the business his father built up (for Chris to inherit), so he rejects it by refusing to have his name on it. If he takes the business or the money from it he knows he is disloyal to his men and ‘forgets’ why they died. He is loyal to his father – he loves his father and thinks he is a great man, better than most. When he finds his father is just an ordinary man who made profit from the deaths of others, he cannot live with this. His father’s loyalties are to his own family only. To Joe this is the only thing that matters, but to Chris other people are just as important. Joe cannot see the wrong he did by killing 21 boys – they were not his sons, BUT they were somebody’s sons and to Chris (and to Larry) this is just as important. Joe made money from death and his excuse is that he did it for Chris. Chris cannot accept this and it makes the business all the dirtier. Also Joe betrayed his best friend and partner by allowing him and his family to be ruined to save himself and his family. In Chris’ eyes this makes his father a weak mouse of a man with no principles and Chris cannot live with this knowledge and so determines to leave. Finally, when Chris realises that Larry was so ashamed of what his father did that he killed himself, he realises it is not enough to turn his back and forget about it. He knows he must do the right thing – the lawful and upright thing, not thinking about himself but of others – and take Joe to the authorities to ‘pay’ for the crime he committed. Chris’ loyalty to others is greater than his loyalty to his father. He is stronger than Joe. He has principles that he will not compromise, not even for his father. He is a noble man, the great man he thought his father was, so he must do the honourable thing. As a result of this and seeing what Chris (and Larry) think of him, Joe kills himself. Joe saw nothing wrong in making money from war/death because thousands of others did too. ‘The whole damn country’s gotta go if I go’, but Chris (and Larry) thought their father was better than the rest. Chris is the good, honourable man he thought his father was. He is not bright, but he has principles and moral courage and he knows what is right. He cannot compromise his beliefs, not even for his father. Key Points for Study in the Play The structure of the play The play has two narrative strands which finally meet. These are: Chris's and Ann's attempt to persuade Kate that Larry is dead, so they can marry. Joe wishes to support them, but sees that he cannot; the attempt by George, then by Chris, to find out the truth of what happened in Joe's factory in the autumn of 1943. A slip of Kate's tongue tells George of Joe's guilt, but he leaves without persuading Chris. Chris and Ann insist on marrying and Joe supports them. This drives Kate (who sees this as a betrayal) to tell Chris the truth. Ann's showing Larry's letter to her convinces Kate that Larry is dead. The letter also answers Joe's repeated question about what he must do, to atone for his crime. He cannot restore life to the dead, but he can give life (free from a sense of moral surrender) back to his living son, Chris. Key Incidents in the play Consider the significance: of the storm, and of Kate's dream; of the arrival of George; of Ann's eventual disclosure of Larry's letter. The stage set Show how the set of the play (the exterior of the Keller house) works as a symbol of Joe's values. Contrasting values Examine the difference between Chris's and Joe's ideals and values. Look, especially, at Chris's speech beginning “...It takes a little time...” and ending “...and that included you”. What does this tell us about Chris's outlook? Before hearing Larry's letter read, Joe says (of Larry) “...for him the world had a forty-foot front. It ended at the building line”. After the letter is read, Joe says, “Sure he (Larry) was my son but I think to him they were all my sons, and I guess they were”. Who are “they”? What does Joe now see Larry's view to have been? How has this changed his (Joe's) outlook? If Joe confessed to the police, he would be jailed for manslaughter and would receive a short sentence (relatively). Yet he chooses to kill himself. Why does he do this? Consider Joe's speech, beginning, “Nothing's bigger than that...”. Look, too, at Kate's final words to Chris: “Forget now. Live”. What has Joe tried to do for Chris by his suicide? A final judgement How does the play present this relationship to the audience? How much do we know (at various points) in relation to those on stage? Who is the more sympathetic character, Chris or Joe? Answering on Specific Aspects of the Text Character The central character of the play (whose tragedy it is) is Joe - how does Miller show this? How is Joe's character shown through his relations with others: Chris, Kate, Ann and Larry? How does the audience's idea of Joe change as the play progresses? How do Chris's speeches help us form an idea of Joe? What is the point of Joe's saying “...they were all my sons”? Why is this phrase the play's title? Why does Joe decide to shoot himself? What do we learn from Joe's comments on Steve (for example, that he wants him to have his old job back, when he comes out of jail)? Although this play is clearly about Joe, other characters are closely connected with him. Comment on how these characters are presented in the play - Chris, Kate, Ann and George. Minor characters - comment on those who are there not as characters in their own right, but to show the audience things about others (e.g. Lydia, Frank and Sue). Comment on Jim Bayliss's special rôle in helping the audience understand the play. Action Comment on things that are not directly shown, but narrated or recalled by characters in the play. Explain how Miller makes use of past events having consequences in the present. Look in the stage directions for examples of physical actions (they may seem trivial or small) and show how they help move the story on. In this play, Miller uses exits and entrances (for example, when people answer the telephone) to bring particular characters together - comment on any examples of this which you can find. Dramatic devices In general, these can be found by looking at stage directions. Comment on any such directions which help explain how the play should be presented. The script for the play opens with a very detailed description of the Kellers' house, which the audience can see throughout the drama. Why is this? Explain its symbolism - especially in relation to Joe's comment on Larry's view of the world (“To him the world had a forty-foot front, it ended at the building line”). Comment on other interesting features of the set, such as Larry's tree. The most obvious feature of drama is perhaps the dialogue - comment on any passages which help the audience understand the action better. (You will find a long list of suggested extracts and long passages elsewhere in this guide.) Comment on the way in which George is a catalyst for the uncovering of Joe's secret. Comment on Miller's use of props in the play (e.g., the newspaper Joe reads at the start of the play, the pitcher of grapefruit juice Kate carries at the start of Act Two). Comment on any interesting features of the production of the play which you have experienced (for example, how it has been adapted for radio). Dramatic structures Explain how the three acts of the play show the structure and plotting of the dramatic narrative. Show how, within each act, Miller arranges the narrative as a series of episodes. How does time in the play relate to the time before the play begins? How does the structure of the play show that justice catches up with offenders eventually - the idea of nemesis? Explain how, in the play, Miller gradually reveals more and more information to the audience, rather as in a detective story. Selected quotations The quotations which appear below contain important references to the principal themes of the play. For the context of the quotation, two page references are given. The first refers to the Penguin paperback edition, in which All My Sons follows A View from the Bridge. The second refers to the Hereford Plays (Heinemann) edition. ...what the hell did I work for? That's only for you, Chris, the whole shootin' match is for you. p.102; p.16 It's wrong to pity a man like that. Father or no father, there's only one way to look at him. He knowingly shipped out parts that would crash an airplane. p.117; p.29 You're the only one I know who loves his parents/ I know. It went out of style, didn't it? p.119; p.31 I owe him a good kick in the teeth, but he's your father. p.136; p.47 None of these things ever even cross your mind?/Yes, they crossed my mind. Anything can cross your mind! p.143; p.54 You had big principles...so now I got a tree, and this one when the weather gets bad he can't stand on his feet...p.148; p.59 Your brother's alive...because if he's dead, your father killed him. Do you understand me now?...God does not let a son be killed by his father. p.156; p.66 ...every man does have a star. The star of one's honesty. And you spend your life groping for it, but once it's out it never lights again...He probably just wanted to be alone to watch his star go out. p.160; p.70 I thought I had a family here. What happened to my family? p.161; p.70 There's nothin' he could do that I wouldn't forgive. Because he's my son ...I'm his father and he's my son, and if there's something bigger than that I'll put a bullet in my head! p.163; p.73 Goddam, if Larry was alive he wouldn't act like this. He understood the way the world is made...To him the world had a forty-foot front, it ended at the building line. p.163; p.73 We used to shoot a man who acted like a dog, but honour was real there ...But here? This is the land of the great big dogs, you don't love a man here, you eat him. That's the principle; the only one we live by - it just happened to kill a few people this time, that's all. The world's that way...p.167; pp.76, 77 I know you're no worse than most men but I thought you were better. I never saw you as a man. I saw you as my father. p.168; p.78 Sure, he was my son. But I think to him they were all my sons. And I guess they were, I guess they were. p.170; p.79 Don't take it on yourself. Forget now. Live. p.171; p. 80 Several long speeches are worthy of close study. The page references below are to the Penguin edition and the Hereford Plays (Heinemann) editions respectively. The speaker's name appears in brackets. Pages 121 to 122; 33 - 34, beginning: “It takes a little time ...” (Chris) Page 157; 67, beginning: “You're a boy ...” (Joe) Page 158; 68, beginning: “For me! Where do you live ...?” (Chris) Page 168; 77 - 78, beginning: “What should I want to do ...” (Joe) Pages 169 to 170; 78 - 79, beginning: “I know all about the world ...” (Chris; this speech contains the text of Larry's letter) Page 170; 80, beginning: “You can be better!” (Chris) Two long speeches by George may also repay study; they are on page 141; 52, beginning: “You can't know ...” and on page 143; 54, beginning: “Because you believed it ...” Suggested Mini-Essay Questions 1. Several characters in the play believe in forces outside their control that influence the events of their lives. Kate turns to astronomy and God, while Keller argues that the pressures of business forced him to act as he did. Examine the role of personal agency in the play. For example, does Keller's suicide reflect a new acceptance of his misdeeds? Does he kill himself out of choice or mainly as a result of external pressures? 2. Keller argues that no one "worked for nothin' in that war," insisting that if he has to go to jail, then "half the Goddam country" is similarly culpable. Is this an indictment of capitalism or of the wartime mentality? Does he believe this argument, or is it mainly another attempt to deflect blame? 3. Did Kate (Mother) know that Larry was dead? Did Chris know that his father was guilty? How might the actors and director of the play keep these questions ambiguous or suggest that these facts were known all along? Did Miller possibly intend that the audience never know how much Kate and Chris had suspicions, or is the play better if the audience gradually learns that Kate and Chris knew the truth all along? 4. Which kinds of facts are better to face immediately, and which kinds are better to deny as long as possible? Consider personal, family, and social values. Use the play for possible anecdotal evidence. 5. The tone of much of the second and third acts is accusatory, with a strong emphasis on questions and questioning. How do the characters use questions to deflect blame? Or, how does Miller use questions to pace the dialogue and heighten the tension? What counts as evidence of the facts? (Consider the courtroom scenes in The Crucible for comparison.) 6. How does Miller introduce the past and show the effects of the past on the Kellers without employing flashbacks? 7. How does Miller manipulate information? The entirety of the first act is exposition, yet the audience is kept guessing and alert through Miller's careful pacing of the revelation of facts. How does our experience of the play change after we have seen it the first time and know all the history? Do successive iterations of reading or watching the play help us pick up on additional details of the themes and characters? 8. The common theatrical device of "the letter" provides a way for Larry to personally enter the play after his death. What else makes the letter work well in this particular play? Consider, for instance, Miller's careful manipulation of information throughout the play. 9. How does Miller characterize Larry, who never appears on stage but who is so fundamental to the events and the people? How can we reconcile or add together the various accounts of his character? 10.If the focus is on the Keller family, what is the point of including the Deever family as more than just a set of foils for the Kellers? Exemplar Critical Essay ‘All My Sons’ by Arthur Miller is a play which portrays a strong relationship between two central characters, Joe and Chris Keller. The play deals with the morality of making money from war adn the two characters represent the opposing sides in this argument. the fate of both characters is determined by the conflict central to the action of the play. In the early stages of the play Miller establishes the very strong relationship between Joe and Chris, father and son. Joe seems an average husband and father in a middle class American home. Chris, his elder son, fought in a recent war and survived. Joe’s other son, Larry, however has not returned from the war and was reported missing in action. Miller makes clear that the memory of Larry and the uncertainty of his death haunt all the central characters of the play for one reason or another throughout its course. The relationship Miller shows us initially between Joe and Chris is a typical father/son relationship: “Joe (laughing): Chris: I got all the kids crazy! One of these days, they’ll all come in here and beat your brains out.” Here, Joe is referring to the game he plays with the local children. He claims he has a jail in his basement and that he is a law-enforcer int he neighbourhood. The irony is this ‘game’ started because Joe had been in jail. He thinks this ‘game’ is funny and ‘plays’ at crime solving with the children. Chris too finds it funny, but the irony in his response is that the youngsters might really want to hurt Joe (as might Chris) if they knew Joe had committed the crime he was imprisoned for. Miller allows the audience to become aware, as the play progresses, that this seemingly close relationship is, in fact, based on a lie. Miller establishes Chris form the beginning of the play as a man of honour and truth, someone we can trust. We believe what he says therefore, and when Chris refers to his father as ‘Joe McGuts’ when Joe tells his version of the day his firm shipped out faulty parts to the army, we trust his judgement and also believe Joe. The problem is that Miller gradually makes us aware that Chris has been taken in by the lie Joe has told about the factory. Joe is, in fact, not the brave man Chris believes him to be. He is a moral coward in that he betrayed his friend and partner by refusing to accept responsibility for his actions, which led to the deaths of 21 yound men. Joe has, in fact, got away with murder. “He simply told your father to kill pilots and covered himself in bed.” The scene is Miller’s turning point in the play, where the audience and family have to face the truth about Joe. He is the moral coward as he betrayed his friend killing pilots ad lying about it, but the worst thing is that he feels no guilt or remorse about what he has done. Ironically he even talks of ‘forgiving’ his partner for what he did. When Miller has the partner’s son, George, confront the family in this scene, Chris is able to see his father for the coward he is for the first time. Miller lets us see Joe is a man who is not well educated, but who has built up a successful business through hard work. However, he protects his business and his family, for whom he has built the business, at the expense of others. He feels no remorse about the fate of the 21 pilots because it was them or him. “You lay forty years into a business and they knock you out in five minutes.” “I did it for you, it was a chance and I took it for you.” Miller has created a character that is entirely self/family centred in Joe. Joe sees nothing wrong in causing these deaths or in blaming his partner for the decision to ship out the faulty parts to the army. He has no principles in life except: succeed at any price and look after your own. The two characters are at opposite ends of the moral spectrum and this is the cause of the conflict which determines the fate of both. when Chris discovers what his father done he is disgusted. “Now if I look, all I’m able to do is cry.” Chris trusted his father and looked up to him. He saw him as his hero. “I know you’re no worse than most men, but I thought you were better. I never saw you as a man, I saw you as my father. I can’t look at you this way. I can’t look at myself!” When Chris says this he’s realised that, despite his disgust at his father’s actions and disappointment in him as a man, he loves him too much to report him to the police. He plans to move away to ‘pretend’ all this did not happen and let his father live his life. Because Chris, our moral character, knows this is wrong and a cowardly reaction, he cannot look at himself. Miller shows us through these lines that Chris looked up to his father and assumed he would always do the right thing and is ashamed of not being able to do the right thing himself by reporting him. However, when Chris discovers the fate of his brother, he knows he must take Joe to the police. Review of All My Sons as performed by: Oedipus & Company There are four names above the title in the ads for the baleful new Broadway revival of Arthur Miller’s “All My Sons.” Three of them are reasonably well known to regular theater- and moviegoers (John Lithgow, Dianne Wiest and Patrick Wilson), and one is very well known to readers of celebrity tabloids (Katie Holmes). But don’t be misled into thinking that these high-profile performers are the stars of the show. Though his face is never seen in the production that opened Thursday night at the Gerald Schoenfeld Theater, the British director Simon McBurney might as well be downstage center at all times, stealing each and every scene from his human props. Mr. McBurney, justly celebrated for his brilliant work as the leader of the experimental London company Complicite, is a conceptual theater artist who has never had much use for straightforward, naturalistic acting. And woe betide the thespian who cannot dance to this godlike auteur’s music. You might wonder why I’m talking like a half-baked imitation of classic tragedy. It is not, as it happens, an inappropriate tone for discussing this intriguing but disconnected interpretation of the 1947 play that made Miller famous. Mr. McBurney has staged Miller’s tale of a self-deluding, guilt-crippled American family with the ritualistic formality and sense of inexorability of Aeschylus and Sophocles. Would that he could summon the primal power associated with those ancients. It’s not as if Arthur Miller and Greek tragedy have never been seen in the same sentence before. On the contrary, assessing this dramatist’s works according to Aristotle’s “Poetics” has been the province of high school English students as well as scholars and critics since Miller’s 1949 essay “Tragedy and the Common Man” (first published in The New York Times), in which he defended the average Joe’s potential as a character of self-sacrificing heroism. But to bring out this aspect of the play as literally as Mr. McBurney does is to underline not only what’s obvious but also what’s awkward in a work that relies heavily on mechanical plotting and bald speechifying. And to transform its characters into archetypal puppets of destiny is to deprive actors of the chance to create richly human portraits. I have seen such portraiture in revivals of “All My Sons” from the Roundabout Theater Company (in 1997) and in particular at the National Theater in London (in 2000), productions that had much of the audience in tears. The preview performance I saw of this one left me stone cold, despite some electric moments from a very fine Mr. Lithgow and Mr. Wilson. The very different leading actresses — the stage veteran Ms. Wiest and the neophyte Ms. Holmes, in her Broadway debut — are sad casualties of Mr. McBurney’s high-concept approach. (My companion at the theater, finding herself dry-eyed at the final curtain, asked, “Is there something wrong with my emotional acuity?”) It’s understandable that producers would think this is an auspicious time to revive “All My Sons,” a heartfelt condemnation of capitalist greed and its concomitant lack of moral responsibility. The plot centers on Joe Keller (Mr. Lithgow), a businessman whose factory was responsible for sending faulty airplane parts overseas, leading to the deaths of American servicemen during World War II. It was Joe’s partner who went to prison for the crime, and now the jailed man’s daughter, Ann Deever (Ms. Holmes), has returned to visit the Kellers. Once engaged to Joe’s younger son, Larry, a pilot who had gone missing several years earlier on a mission, Ann has been corresponding with Larry’s brother, Chris (Mr. Wilson), and it looks as if a new romance is blooming. This is not to the liking of Kate Keller (Ms. Wiest), who refuses to concede the possibility that Larry is dead. It isn’t just a mother’s possessive love that has brought her to this state of fanatical denial; there are more far-reaching reasons, which emerge in a climactic night of reckoning. In any production of “All My Sons” a certain unease will be evident from the beginning. But the play’s force lies in Miller’s portrayal of how its characters come to identify and reckon with the sources of this unease, as what initially appears as a sunny small-town idyll turns dark and stormy. Mr. McBurney’s production, which consistently highlights the implicit in thick strokes, begins with the cast filing onto the set. An actor (Mr. Lithgow) announces the title and author of the play and reads from the script’s directions, à la the stage manager in Thornton Wilder’s “Our Town.” Mr. McBurney sustains this particular distancing device by having the ensemble members sit, within our view, on the sidelines. The production has other ways of reminding us that what we’re watching is a sort of mythic (and artificial) theatrical rite. Tom Pye’s set is a rectangle of green, green grass, with a screen door in the middle, behind which hovers a ghostly Magritte-like image of a house. Words announcing changes of scene are projected, as is video footage portraying factory assembly lines, soldiers at war and, for the conclusion, that vast sea of humanity (embodied by a contemporary street crowd) whom we must acknowledge as our responsibility. (The projection design is by Finn Ross for Mesmer.) The leading performers make their entrances and exits glacially, in robotic profile, across the back of the stage. When they speak, they often find themselves competing with anxious, portentous music, which might as well be a floating road sign marked “Doom Ahead.” Finding a stylized acting approach that matches the dark-gray atmosphere isn’t easy, and few of the cast members succeed. Most of them appear to have been encouraged to go for the sinister, whether the scene asks for it or not. Damian Young, as the Kellers’ neighbor, a disenchanted doctor, and Christian Camargo, as Ann’s angry brother, deliver their big monologues with the half-mad intensity of supporting players in a Vincent Price movie. Ms. Wiest assumes a glazed demeanour and reproachful stare, becoming Joe’s conscience incarnate or a Cassandra according to Norman Rockwell. (She drops her g’s, Sarah Palin style, to convey Kate’s hometown folksiness.) And while Ann is supposed to arrive at the Keller household with high hopes and good intentions, Ms. Holmes delivers most of her lines with meaningful asperity, italicizing every word. This Ann is straight from the school of the Erinyes (those avenging furies from Greek mythology), and I didn’t believe for a second that she really loved the honourable, naïve Chris. Mr. Wilson and Mr. Lithgow, actors of strong and confident naturalism, come off better, especially in their scenes with each other. In Joe and Chris’s big Oedipal showdown in the second act, these actors powerfully evoke those painful moments when a family quarrel can feel like an earthquake. It’s the only scene where Mr. McBurney’s shaping concept feels fully justified, where you see how the production might have worked. Mostly this vaunting interpretation falls into that same limbo between intention and execution where so many of Miller’s baffled American souls find themselves. ALL MY SONS By Arthur Miller; directed by Simon McBurney; sets and costumes by Tom Pye; lighting by Paul Anderson; sound by Christopher Shutt and Carolyn Downing; projection design by Finn Ross for Mesmer; wig design by Paul Huntley; associate producers, Cindy Tolan, A. Asnes/A. Zotovich and M. Mills/L. Stevens; production stage manager, Andrea (Spook) Testani; technical supervisor, Nick Schwartz-Hall; company manager, Kimberly Kelley; general manager, Richards/ Climan, Inc. Presented by Eric Falkenstein, Ostar Productions, Barbara H. Freitag, Stephanie P. McClelland, Scott Delman, Roy Furman and Ruth Hendel, in association with Hal Luftig, Jane Bergère and Jamie deRoy. At the Gerald Schoenfeld Theater, 236 West 45th Street, Manhattan; (212) 239-6200. Through Jan. 11. Running time: 2 hours 10 minutes. WITH: John Lithgow (Joe Keller), Dianne Wiest (Kate Keller), Patrick Wilson (Chris Keller), Katie Holmes (Ann Deever), Becky Ann Baker (Sue Bayliss), Christian Camargo (George Deever), Michael D’Addario (Bert), Danielle Ferland (Lydia Lubey), Jordan Gelber (Frank Lubey) and Damian Young (Dr. Jim Bayliss). http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/17/theater/reviews/17sons.html?_r=1 All My Sons: a play for Obama's America? I was greatly moved by Simon McBurney's current sellout Broadway revival of Arthur Miller's play All My Sons when I caught a recent, pre-election, matinee. But, it wasn't until I stayed up through the night in London to watch Barack Obama sweep all before him, that I finally grasped in what particular way McBurney's production delivers. I wonder, is it possible for a theatre production to be politically prescient; to capture the mood of the times without fully realising it? By lifting a 1947 text out of anything resembling naturalism, and adding film and video footage that lands it in the here and now, the English director has turned a quintessentially American domestic drama into a piece about human interconnectedness and social responsibility. In this staging, the "all" of the title carries real force: no one is left out of Miller's critique. There are, of course, Broadway precedents for this approach. In 1994, Stephen Daldry won the Tony Award for best director for his New York version of An Inspector Calls, a JB Priestley play which curiously, like Miller's, dates from 1947. Daldry's production smashed open the Birling family confines, to confront them with a broader, more brooding world beyond. Similarly, All My Sons offers a stage full of unnamed witnesses to events who pay silent acknowledgment to a story of misdeeds, deception, and passing the buck - in other words, the very stuff of which the Bush regime was made. This ability to elide the public and the private - to find the political impetus in what could be merely familial - gives a genuine sting to McBurney's production, which couldn't be further removed from the drearily literal-minded revival that played a few doors down on 45th Street, in 1987. Much of those elisions rang out to many of us when Obama emerged in the wee hours of Wednesday morning to deliver his acceptance speech. There were, of course, the entirely proper tributes to his wife and daughters, but those came after Obama's history-making acknowledgment of a citizenry seen fully in the round: not just Democrat or Republican, black or white, but also "Hispanic, Asian, Native American, gay, straight, disabled, and non-disabled." In eight years of Dubya, I don't recall the current president even voicing those words. In any case, All My Sons is presently playing to the sorts of crowds usually associated with large-scale musicals. This can't all be attributed to the fact that it features Katie Holmes (aka Mrs Tom Cruise), in a feisty, perfectly credible supporting turn. I think much of the show's success derives from the same desire for clarity, truth-telling and America's overdue reckoning with itself that has helped land Obama the White House. Last month, I wrote about Broadway's apparent reluctance to tap into the mood of the times, but that was before this play had opened. Now that it has, drama shows itself capable of buttonholing all of us right here, right now. Arthur Miller would, I suspect, be pleased. http://www.guardian.co.uk/stage/theatreblog/2008/nov/06/arthur-miller-broadway-obam