Section 7: Conformity and Obedience

advertisement

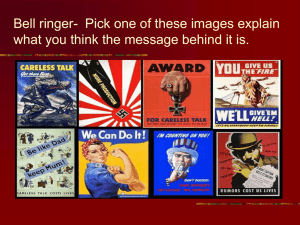

Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 1 Section 7: Conformity and Obedience Part 1: Overview The purpose of this section is to explore essential questions such as: ? What are the factors that influence the choices we make? ? What does it mean to be treated as less-than-human? Under what conditions, does dehumanization take place? ? Under what conditions are people more likely to obey authority? Under what conditions are people less likely to obey authority? The lesson ideas for this section are built around these core resources: The Nazis: A Warning from History, episode 2, Chaos and Consent (film) Nazi propaganda posters Childhood Memories (film) Readings from Chapter 5, Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior Obedience (film) Background information To support the teaching of this section, we strongly recommend reading chapter 5 in the resource book Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior. For more historical background we recommend: Propaganda (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum) Dehumanization (The Lucifer Effect) Blind Obedience (The Shoah Education Project) German Propaganda Archive (Calvin College) Media Literacy (PBS) Rationale: What is the purpose of this section? Why teach this material? Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 2 Part 2: Lesson ideas These lesson ideas suggest ways to the core resources in order to support students’ exploration of the section’s’ essential questions. They should be adapted to meet the needs of your students and context. . Lesson idea #18 – Propaganda and conformity Suggested duration: 90-120 minutes Key terms: propaganda, conformity, dehumanization Materials: The Nazis: A Warning from History, episode 2, Chaos and Consent (24:00 – 38:27) • (Handout 18.1) Definitions of propaganda • (Handout 18.2) ”Healthy Parents Have Healthy Children” • (Handout 18.3) The Poisonous Mushroom • (Handout 18.4) Hitler Youth Poster • (Handout 18.5) “Trust No Fox on His Green Meadow and No Jew on His Oath” Recommended journal and discussion prompts • • • • • • • • Identify an example of conformity from your own experience. In what ways did you conform? What were the benefits of conforming? What were the costs of conforming? Identify a time when you or someone you know went along with the group even though you/he/she did not agree with what they were doing? What were the benefits of “going along”? What were the costs? What do you think of this decision? If you wanted to convince people to believe a certain idea, what might you do? What are some ways you might persuade people to agree with you? Do you strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree with the following statement: Most people can be convinced to believe almost anything. Explain your answer. Under what circumstances do you think people are less likely to believe what they see or hear? Under what circumstances do you think people are most likely to believe what they see or hear? A few months after becoming Chancellor of Germany, Hitler created a Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Why do you think Hitler might have done this? What might the director of a Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda do? What criteria do you use to determine what information is accurate and can be trusted? How would you find out if information is misleading or inaccurate? What does it mean to dehumanize someone? Under what conditions, if any, is it appropriate to intentionally manipulate information to achieve a desired result? When selling a product? When promoting a political cause? How can we distinguish between the ethical dissemination of information and unethical dissemination of information? Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 3 Activity ideas Watch excerpt from The Nazis: A Warning from History, episode 2, Chaos and Consent (24:00 – 38:27) - This excerpt from the BBC-produced documentary The Nazis: Chaos and Consent describes life in the Third Reich from January 1933 when Hitler came to power until violence against Jews escalated with Kristallnacht in November 1938. This excerpt provides a review of material students have already covered, including the Nuremberg Laws. It also introduces concepts central to this lesson such as conformity and propaganda. • Pre-viewing: Before watching this clip, ask students to consider the question, “What influences your beliefs and actions?” Record a list of their responses on the board. You can also ask students to identify an idea they wish everyone believed or behavior they wished everyone practiced. What could they do to get as many people as possible to believe this idea or to act in this way? These questions begin to get students thinking about conformity and persuasion.. • During-viewing: Ask students to record evidence from the film to answer the question, “What are some ways the Nazi dictatorship encouraged people to follow their policies and embrace their ideals?” • Post- viewing: In the clip, Erna Kranz recollected her feelings as a young woman living in Nazi Germany who witnessed violence and injustice against Jewish people. Here is a transcript from the video: Erna Kranz: It was quite a shock….You actually thought about things more…. At first you allowed yourself to swim with the tide. You were carried along on a wave of hope, because we had it better, we had order in the country, we felt secure. But, then you really started to think. Me, personally, that is….It was a terrible shock. I have to admit it. Interviewer: But you didn’t become an opponent of the regime. Erna Kranz: No, no, no, that, no. One could have, then. But when the masses were shouting “Heil,” what could one do? You went with it. We were the ones who went along. After reading these words or watching this clip again, ask students to reflect in their journals on the following questions: • Why do you think Erna decided to be part of the group “who went along”? • What options did she feel she had? • Erna asks, “What could one do?” How might you answer her given what you know about the time period? Analyzing Erna’s experience provides an opportunity to create a working definition for “conformity” (or for students to review definitions they may have developed during section three). In their journals, students could reflect on questions such as, “What does conformity mean to you? Identify an example of conformity from your own experience. What are the benefits of conforming? What are the costs of conforming?” Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 4 Create a working definition for propaganda -The materials in this lesson help students address the question “Why did most Germans, like Erna, go along with the policies dictated by Hitler and the Nazi Party?” by examining the role of propaganda in German society. Before they begin analyzing Nazi propaganda, help students come up with a working definition for propaganda. Here are some other ways to help students think more deeply about this concept: o Handout 18.1 includes several definitions of propaganda you might share with students to help them think about the different meanings of this word. o The reading “Propaganda,” on pp. 218-19 of the resource book, describes how Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels and Hitler believed they could use a range of media to control the beliefs and actions of German citizens. Students could read “Propaganda” for homework in preparation for this lesson. One important point made in this reading is how the Nazis used language to control how Germans thought about themselves, their nation and their neighbors. For example, the Nazis referred to workers as “soldiers of labor.” o At this point, you might want to remind students that within the first few months of being appointed Chancellor, Hitler created a Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. The United States federal government, like many nations, has ministries (or departments) of defense, treasury, and education, but does not have a department of propaganda. In Nazi Germany, what might the director of a Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda do? What purpose might it serve? They could write about this question in their journals and then share responses with a partner. Analyzing Nazi Propaganda– Facing History teachers have found that one of the most effective ways to help students understand life in the Third Reich is through studying the propaganda disseminated by the Nazis. Handouts 18.2 - 18.5 provide several examples of Nazi propaganda distributed during the 1930s - two posters and a page from a children’s book. These images exemplify Nazi propaganda that was targeted at young people. For other examples of Nazi propaganda, refer to the German Propaganda Archive at Calvin College which posts speeches, posters, and political cartoons. Also, Facing History’s library has a set of propaganda slides available for borrowing. • Describe, interpret, evaluate: For a structured way to help students analyze Nazi propaganda, refer to the teaching strategy Media Literacy: Analyzing Visual Images. This strategy guides students through the process of describing, interpreting and evaluating what they see. To model how to answer questions with specific evidence from the image analyze the first image together as a whole class. . Students can analyze other images in small groups or independently. After this exercise, students can discuss the extent to which these examples fit the various definitions of propaganda on handout 18.1, as well as any working definitions they have developed. • Propaganda and dehumanization: Once students have analyzed several examples of Nazi propaganda, they are prepared to discuss how these images may have impacted the millions of Germans who saw it. As students will likely discover, Nazi propaganda served many purposes: to glorify the pure German race, to encourage obedience to Hitler, and to promote specific gender stereotypes. One of the main purposes of Nazi propaganda was to Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 5 dehumanize Jews – to make them appear unworthy of the dignity and respect afforded to human beings. Introduce students to the term dehumanization. Questions you might use for journal writing and/or discussion include: o What does it mean to dehumanize someone? o How might this be accomplished? o What might be the consequences of dehumanizing an individual or group? Once people believe that someone is sub-human, how might that individual be treated? o Identify examples of dehumanization from other periods of history. What group was dehumanized? By whom? What were the consequences of this? Discussing the impact of propaganda: After seeing a Nazi propaganda film called The Eternal Jew, a graduate student in Nazi-occupied Holland named Marion Pritchard said: It was so cruel . . . that we could not believe anybody would have taken it seriously, or find it convincing. But the next day one of the gentiles [non-Jews] said that she was ashamed to admit that the movie had affected her. That although it strengthened her resolve to oppose the German regime, the film had succeeded in making her see Jews as “them.” And that of course was true for all of us. The Germans had driven a wedge in what was one of the most integrated communities in Europe.1 You might end this lesson by sharing this quotation with students and asking them to reflect on how they think images from the media might have influenced their lives. Have they ever felt like Marion Pritchard? After seeing a movie or an advertisement or listening to a song, have they ever felt like an idea stuck with them, even though they questioned whether this idea was true? ? Below are some other questions that can provide a starting point for a class discussion or a personal essay assignment. You might give students this list of questions and allow them to respond to the one that most interests them. In small groups, students can comment on each other’s ideas using the Save the last word for me teaching strategy. Does propaganda have to be misleading? Does it have to be untrue? Is it always harmful? ? In Nazi Germany, propaganda had deadly consequences. What are the consequences of propaganda or ideas and images from the media on lives today? ? Can you think of positive uses for propaganda? Where is the line between the appropriate use of media to persuade and the misuse of media to inflict harm? ? What criteria can we use to determine whether what we see and hear can be trusted? ? Hitler is known for saying, “What good fortune for governments that people do not think,” and his policies were based on the premise that most individuals are conformists who do not think for themselves. What do you think this statement suggests about human behavior? Do you agree? Why or why not? ? Based on your understanding of the history of Jews in Germany (and Europe), to what extent was Nazi propaganda creating new prejudices? To what extent was Nazi propaganda reinforcing existing prejudices? In general, do you think propaganda is more likely to 1 Marion Pritchard as quoted in The Courage to Care, ed. Carol Rittner and Sondra Myers (New York: New York University Press, 1986), 28. Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) ? page 6 reinforce existing prejudices or create new ones? Explain your answer drawing on examples of propaganda from today or other time periods. The Nazis used several tactics to control information; including limiting access to media that they thought was offensive. They organized public book burnings, censored the media, and banned particular authors and artists. What have been your experiences with censorship? What are the reasons why a person, group, or government may want to restrict access to certain information? Under what circumstances, if any, do you think censorship is appropriate? Why? Assessment ideas (for class work and/or homework) The German Propaganda Archive at Calvin College has a large archive of Nazi propaganda posters. Students can pick a different poster and analyze it on their own. They can share the poster and their analysis with students in class the next day. • To evaluate students’ understanding of propaganda, you could ask them to select an example of propaganda today and analyze this artifact following a similar protocol used during this lesson. • Many of the questions included in this lesson idea could be used as prompts for a formal essay assignment. Extensions: Analyzing Contemporary Media - Students are surrounded by advertisements and other media that are intended to influence public opinion. The media, intentionally or unintentionally, disseminate ideas about race, gender, age, class and the messages individuals, especially young people, pick up from the media can have a profound impact on how they define themselves and how they are defined by others. To expose and demystify these messages, ask students to interpret media in their lives. Here are some ways you can help students develop their media literacy skills while also giving them an opportunity to think about how the media influences how they see themselves and how they see others. • Have students look for examples of how a group (families, men, women, teenagers, African Americans, Latinos, etc.) is represented by the media (by a song, a newspaper article, advertisements in magazines, etc.). To what degree (a lot, somewhat, not much) does the media’s portrayal of this group match the student’s own characterization? This exercise can lead into a discussion about the relationship between the media and identity. How do the media shape who we are and how we see others? In what ways can this be helpful? In what ways can the media be harmful? • Students can bring in examples of propaganda, either found on the Internet, in magazines, or on television, and then discuss why they think this text should be classified as propaganda based on the definitions they developed in class. To complicate students’ work with propaganda, include an example of media with a “positive” message, such as a public service announcement. Students could organize the examples of contemporary propaganda they have collected on a continuum from most ethical to least ethical. Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 7 Create propaganda posters - After students analyze propaganda from Nazi Germany and from today, give them the opportunity to create their own propaganda posters. Begin by having students select a cause or message that is important to them. Then they can identify an appropriate audience for this message and then they can brainstorm tactics that might be persuasive to this audience. For more information about propaganda techniques, two helpful resources include the Institute for Propaganda Analysis and the Sourcewatch web site. Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 8 (Handout 18.1) Definitions of Propaganda Definition #1 - The spreading of ideas for the purpose of helping or harming an institution, a cause, or a person (Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary) Definition #2 - Information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote a political cause or point of view. (Source: Concise Oxford English Dictionary) Definition #3 - A manipulation designed to lead you to a simplistic conclusion rather than a carefully considered one. (Source: Dr. Anthony Pratkanis, Professor of Psychology, University of California Santa Cruz) Definition #4 - The deliberate, systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions [thoughts], and direct behavior to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the propagandist. (Source: Propaganda and Persuasion, Garth Jowett and Victoria O’Donnell, 1999) Write your own working definition of propaganda: Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 9 (Handout 18.2) ”Healthy Parents Have Healthy Children” The caption on this poster reads: "Healthy Parents have Healthy Children." Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 10 (Handout 18.3) The Poisonous Mushroom The text on this age from the German children's book, "Der Giftpilz" (The Poisonous Mushroom) reads, . "Just as it is often very difficult to tell the poisonous from the edible mushrooms, it is often very difficult to recognize Jews as thieves and criminals." Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) (Handout 18.4) Hitler Youth Poster “Youth Serves the Fuhrer: All Ten Year Olds into the Hitler Youth” Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION page 11 Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 12 (Handout 18.5) Trust No Fox on His Green Meadow and No Jew on His Oath This picture comes from the children’s book Trust No Fox on His Green Meadow and No Jew on His Oath,. which was used in many German schools. 2 2 http://www.calvin.edu/academic/cas/gpa/fuchs.htm Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 13 Lesson idea #19 – “He alone who owns the youth, gains the future” Suggested duration: 60-90 minutes Key terms: propaganda, conformity, civic education Materials: Confessions of a Hitler Youth (video), chapters “Hitler Youth” and “Nuremberg” Childhood Memories (video), chapters “Frank S.” and “Walter K.” • Readings from Chapter 5 of Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior • (Handout 19.1) Definitions of propaganda • (Handout 19.2) Life for German Youth (1933-1939) – Sample Analysis Worksheet Recommended journal and discussion prompts • • • • What messages does society send to young people today about the proper way to think and act? Where do these messages come from? To what extent do you agree or disagree with these messages? Hitler said, “He alone who owns the truth, gains the future.” What do you think he meant by this? Do you strongly agree, agree, disagree or strongly disagree with this statement? Explain. If you were designing a school that was supposed to prepare young people for their role as citizens in a democracy, what would it be like? What would students learn? What would happen at this school? How might this school be different than one that was preparing students for their role as citizens in a dictatorship? Where is the line between education and indoctrination? What is the difference between education and propaganda? Activity ideas Preparation – The purpose of this lesson is to help students explore the different strategies the Nazis used to prepare young Germans for their role as obedient followers of Hitler. You might begin this lesson by having students think about the purpose of education, especially civic education. Any of the suggested journal questions could be used to prompt students’ writing and discussion. In addition to journal writing, we suggest having students view two chapters, “Hitler Youth” and “Nuremberg,” from the video Heil Hitler: Confessions of a Hitler Youth. In these chapters, Alfons Heck, a high-ranking member of the Hitler Youth, describes how peer pressure and propaganda helped Hitler and the Nazis recruit eight million German children to participate in the “war effort.” Handout 19.1, a viewing guide for these chapters of this film, follows the levels of questions strategy, including questions ranging from factual to inferential to universal. You could use this handout, or you could simply ask students to describe what they saw and heard in the film and then interpret the significance of this information. What Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 14 does this clip reveal about growing up in Nazi Germany? Where do they see evidence of the influence of propaganda? Of conformity? Explore other narratives describing life for German youth in the 1930s - The Nazis focused much of its propaganda on the youth. Hitler often spoke of the importance of indoctrinating German youth to Nazi ideals. In a 1935 speech to Nazi party officials, Hitler declared, “He alone, who owns the youth, gains the future,”3 and four years later he announced, “I am beginning with the young. . . . With them I can make a new world.”4 You can ask students to discuss why they think the Nazis would focus so much attention on the youth. Then explain that they will be exploring different texts that represent many of the choices, pressures and experiences facing German youth in the 1930s. • Facing History and Ourselves, working with Yale University, has produced Childhood Memories, a video montage of Holocaust survivors, many of whom share stories of what it was like to grow up in Nazi Germany and attend German schools. We especially recommend having students view the testimonies of Frank S. and Walter K. before reading one or more of the following texts from the resource book: “Changes at School,” pp. 175–76 “School for Barbarians,” pp. 228–31 “Belonging,” pp. 232–35 “Propaganda and Education,” pp. 242–43 “Racial Instruction,” pp. 243–45 “School for Girls,” pp. 245–46 “A Lesson in Current Events,” pp. 246–48 • Students can analyze these texts using a process similar to the one they used when interpreting Nazi propaganda in the previous lesson. Handout 19.2 is a sample worksheet designed to break down the interpretation process for students. You can model this process by analyzing one of the clips from Childhood Memories as a whole class before students engage in this process independently or in small groups. • The jigsaw teaching strategy is an effective way to structure students’ reading and sharing of ideas from various texts. • Encourage students to connect what they are reading to other material they have covered, such as the story of Alfons Heck or the propaganda posters. In groups or individually, students can use the text to text, text to self, text to world strategy to help identify these connections. These reflections can prepare students for a debrief discussion focused around the question, “What was it like growing up in Nazi Germany?” Students’ responses should reference the extreme degree of conformity that was influenced by government policies and propaganda. Defining and discussing civic education – Nazi Germany was not the only government to make civic education an important priority. Many nations, including the United States, have said that one of the purposes of schooling, especially public schooling, is to prepare the young for their 3 4 DM DM Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 15 role as citizens. After reflecting on what kinds of citizens were desired in Nazi Germany and how schooling was adapted to achieve this goal, students can reflect on civic education in their own society. Before beginning this discussion, students can create working definitions for the phrase “civic education.” In small groups, students can respond to the following prompt and then share their answers with the whole class: If you were designing a school that was supposed to prepare young people for their role as citizens in a democracy, what would it be like? What would students learn? What would happen at this school? How might this school be different than one that was preparing students for their role as citizens in a dictatorship? Assessment ideas (for class work and/or homework) • • Students’ responses to the questions on the viewing guide (handout 19.1) and/or their analysis of suggested videos and readings (see handout 19.2) will reveal the degree to which they understand the role of propaganda and conformity in the lives of German youth. Have students add to their definitions of conformity and propaganda. They can turn in an exit card with their revised understanding of these terms. Or, you can ask them to identify a specific way that these concepts played out in the lives of German youth. Extensions: Civic education debate - The materials in this lesson might spark students’ interest in civic education. Students could research what their school, district, or state mandate in terms of civic education. They could also analyze civics or history textbooks. Another way to deepen students’ understanding of civic preparation in a democracy is to organize a debate on the topic. Students can take positions on statements such as: • The purpose of public schools is to prepare youth for their role as citizens. • Schools today do a good job of preparing young people to be effective democratic citizens. • It is appropriate for schools to teach youth about the norms valued in that society. The following teaching strategies provide useful structures for classroom debates: SPAR, barometer, and four corners. Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 16 (Handout 19.1) Heil Hitler: Confessions of a Hitler Youth – Viewing Guide Questions for “Hitler Youth” • • • • • • • • • • • Approximately how many children pledged themselves to Hitler and the Third Reich? How old was Alfons when he joined the Hitler Youth Corp? Identify at least 3 examples of propaganda that Alfons said had an impact on him. How did the propaganda impact him? How did the Nazis try to attract young people to their cause? (Identify at least three strategies they used.) What do you think was the intended purpose of showing films like The Eternal Jew and Hitlerjugend Quex? Which film did Alfons say had a greater impact on him? Why do you think that might have been the case? What is racial science? Why do you think people believed it? How do you think learning about racial science influenced young school age children? Why do you think the Nazis targeted the youth? Why did they devote so much time to their education and training? What does this film reveal about how the Nazis taught young Germans about distinctions between we and they? What do you think might be the impact of these lessons? According to this film, how were the Nazis trying to shape the morals of the young? What were they teaching was the “right” way to behave? The “wrong” way to behave? To what extent do you think it is possible for governments to shape the morals of its citizens? What shapes your morals and beliefs? Questions for “Nuremberg” • • • • • • • • • • Where did the Nazis hold the Annual Nazi Party Conference? What was the purpose of this conference? What “mesmerizing” message did Hitler give the Youth Corp? Why do you think Hitler referred to young people as “his?” What are some feelings Alfons experiences at the Nazi rally in Nuremberg? Why do you think belonging to the Hitler Youth is important to Alfons? Do you think belonging to a group is important to teenagers today? Why or why not? Identify an example of obedience in this film. Who is obedient? To whom? Why? Identify an example of conformity in this film. Who is conforming? To what norm or set of behaviors? Why? What are the benefits of having a charismatic government leader? What are the dangers of having a charismatic government leader? (Handout 19.2) Life for German Youth (1933-1939) – Sample Analysis Worksheet Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 17 Based on the information in this text (video or reading), what message is being sent to German youth?Who was sending this message? (In other words, who is the “messenger?”)? What might be the purpose of disseminating this message? How might this message influence the thoughts and actions of German youth? Who else might have been impacted by this message? How so? What questions or thoughts does this document or video raise for you? Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 18 Lesson idea #20 – Obedience Suggested duration: 60-90 minutes Key terms: obedience, unconditional obedience, authority, resistance Materials: Obedience (video) • From Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior: o “A Matter of Obedience” pp. 210-212 o “Birthday Party,” pp. 237–40 o “A Matter of Loyalty,” pp. 240–41 o “Models of Obedience,” pp. 235–37 o “Rebels without a cause,” pp. 249-250 Recommended journal and discussion prompts • • • • • • Think of a time when you obeyed a rule or an authority figure (a parent, teacher, group leader, etc). Why did you obey? What were the consequences of your decision? Now think about a time when you ignored or disobeyed a rule or an authority figure? Why did you resist authority? What were the consequences of your decision? What is obedience? What factors encourage obedience to authority? What is resistance? What factors encourage resistance to authority? Under what circumstances are people are more likely to obey authority? Why? Under what circumstances are people are more likely to resist authority? Why? Under what conditions do people act against their conscience? Activity ideas Think-pair-share: Ask students to identify specific moments of obedience from their own lives. You could use a prompt such as: Think of a time when you obeyed a rule or an authority figure (a parent, teacher, group leader, etc). Why did you obey? What were the consequences of your decision? Now think about a time when you ignored or disobeyed a rule or an authority figure? Why did you resist authority? What were the consequences of your decision? In the sharing portion of this exercise, focus on the reasons why students choose to obey and to resist authority. Defining obedience and resistance– To prepare students to learn about Professor Stanley Milgram’s study, have them create working definitions for obedience and resistance. In prior lessons when discussing questions such as, “Why did so many Germans follow the Nazis’ policies?” and “What was it like growing up in Nazi Germany?” students may have already raised “obedience” as a factor that influenced decision-making at this time. Remind students of these conversations as they brainstorm examples of obedience and resistance from their study of Nazi Germany thus far. You could also ask students to react to the adjectives Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 19 “obedient” and “resistant.” Do they think of these as positive or negative qualities? At this point, the purpose of asking these questions is to pique students’ thinking and help them articulate their initial thoughts. At the end of this lesson, students can review their journal entries and note how their ideas may have changed. Watch Obedience: The film Obedience is a 45-minute documentary about Stanley Milgram’s famous experiment which demonstrated the human tendency to obey authority. We strongly recommend that you watch the entire film before deciding whether or not it is appropriate for your students. To allow ample time for preparation and debrief, many teachers show students only excerpts of the film. Excepts commonly used include: • (9:30-11:45) – The “teacher” (subject) refuses to go along with the experimenter’s instructions • (21:50–35:15) – The “teacher” volunteer obeys the instructions of the test administrator to the most advanced degree • (39:40-44:17) - Milgram describes variations to the experiment and how that influenced the results. In particular, this excerpt shows how subjects were influenced by the actions of people around them. When the group obeyed, the subject was more likely to obey, and vice versa. Thus, this clip can be useful in helping students consider the relationship between conformity and obedience. In addition to or instead of viewing Obedience, students can read “A Matter of Obedience” (pp. 210-212). This reading provides a description of this experiment. • Pre-viewing: Give students some background information about Milgram’s experiment through a brief lecture or by having students read the following excerpt from “A Matter of Obedience”: Working with pairs, Milgram designated one volunteer as “teacher” and the other as “learner.” As the “teacher” watched, the “learner” was strapped into a chair with an electrode attached to each wrist. The “learner” was then told to memorize word pairs for a test and warned that wrong answers would result in electric shocks. The “learner” was, in fact, a member of Milgram’s team. The real focus of the experiment was the “teacher.” Each was taken to a separate room and seated before a “shock generator” with switches ranging from 15 volts labeled “slight shock” to 450 volts labeled “danger–severe shock.” Each “teacher” was told to administer a “shock” for each wrong answer. The shock was to increase by 15 volts every time the “learner” responded incorrectly. The “teacher” received a practice shock before the test began to get an idea of the pain involved. Before viewing, some teachers ask students to form a hypothesis about the results of Milgram’s study by answering questions such as: • What percentage of volunteer “teachers” do you think will refuse to give the “learner” any electric shocks at all? • What percentage of volunteer “teachers” do you think will refuse to give electric shocks of more than 150 volts? • What percentage of volunteer “teachers” do you think will give shocks up to 450 volts (labeled “danger–severe shock”)? Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 20 Record students’ hypotheses on the board so they can be reviewed after students learn the results of Milgram’s experiment. Before you show the video, you might also share Milgram’s hypothesis with the class: he predicted that most volunteers would refuse to give electric shocks of more than 150 volts. • During-viewing: While viewing this clip, ask students to closely observe the behavior of the “teacher” and the test administrator. Provide frequent opportunities for students to write in their journals about what they have viewed, for example by pausing after selected excerpts. Two-column note-taking can be a useful structure to help students capture information about what they observe as well as their reactions (feelings, questions, comments) to this information. To provide more structure for students’ note-taking, ask them to respond to specific questions such as: • What language is used by the experimenter and the “teacher”? • What is the teacher’s body language? • How does the teacher act as he administered the shocks? What does he say? • What pressures were placed on the teacher as the experiment continued? • How does viewing this film make you feel? What ideas and questions does it raise for you? This film has been known to provoke strong emotional reactions in students. Many teachers have been surprised when students laugh at sensitive moments of the documentary. This laughter can be interpreted in many ways, but often it is a sign of discomfort or confusion, not of enjoyment. Those who study human behavior say that laughter can be a way of relieving tension, showing embarrassment, or expressing relief that someone else is “on the spot.” You might share these findings with students so that they see laughter as something other than an indication of humor or foolishness. • Post- viewing: Teachers who have used this film comment on the importance of planning sufficient time for debriefing during that class period, making sure that students process their reactions before moving on to their next class. Leave time for initial reactions to the film, as a whole class discussion or as a think-pair-share. There are so many ways that this film can be a springboard to deep discussions about obedience and conformity in the past and today. You might begin by asking students to generate a list of questions that they want to talk about. As you discuss, make sure students know that 65 percent of the volunteers gave the “learner” the full 450 volts. (You may want to remind students that the “learner” in the experiment was a member of the research team and was not actually receiving any electric shocks.) In addition to students’ own questions, here are examples questions that teachers have used following this film: ? What were the results of this experiment? ? Why do people go all the way to 450 volts? Why do some refuse? ? What does this study teach us about human behavior? ? What does this study teach us about Nazi Germany? ? What conclusions does Milgam draw from this experiment? To what extent do you agree with his conclusions? Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) page 21 ? How do the results of this experiment relate to what you know about other moments in history? ? How do the results of this experiment relate to what you have observed or experienced about people today? ? How do people learn to be obedient? Do you think this is something that is taught to people or is it just an instinctive part of human nature? Explain. ? How should young people, especially, be taught to approach issues of obedience? What should they learn about obeying authority? How might they be taught these lessons? ? Milgram concluded that “relatively few people have the resources to resist authority.” What do you think he meant this statement? To what extent do you agree with this statement? What resources are needed to resist authority? How might someone acquire or develop these resources? ? Some people make a distinction between obedience and “blind obedience.” How can you explain the difference between these concepts? Under what conditions might someone obey “blindly”? The Think-pair-share or fishbowl teaching strategies can be used to structure a class discussion. Or, small groups of students can select one or more of these questions to discuss and then they can share the highlights of their discussion with the larger class. Obedience and resistance in Nazi Germany: While most Germans obeyed the Nazis’ policies, they did not do so to the same degree: some barely obeyed while others went even farther than the Nazis’ orders. And, a minority of Germans resisted Nazi authority. The following readings in the resource book reflect the range of responses to Nazi policy: • “Birthday Party,” pp. 237–40 • “A Matter of Loyalty,” pp. 240–41 • “Models of Obedience,” pp. 235–37 • “Rebels without a cause,” pp. 249-250 Students can read one or more of these and then meet in a small group to discuss the range of responses to Nazi policies. One way to structure this activity is to have students identify examples of barely following orders, following orders, following orders to an extreme, and resistance (not following orders). Groups can then discuss how this evidence supports and/or refutes the results of Milgram’s study and suggest other factors, in addition to obedience, that might have influenced the choices made by German youth. Exploring the ethical dimensions of obedience and resistance - For societies to function it is critical that individuals obey authority. The purpose of this lesson is not for students to come away with the idea that obedience is “bad” but to develop their ability to draw distinctions between situations when it is appropriate to obey authority and situations that call for resistance to authority. Here are some ways you can help them hone this skill: • Ask students to create examples of situations when it is good, and even vital, that individuals obey authority. For example, as a matter of public safety, when a mayor asks citizens to leave town before a hurricane, it is important that residents of that town Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (ce) • • page 22 listen. Then, ask students to brainstorm examples that call for resistance to authority. These examples could come from history or from students’ own experiences. Working in groups, students can create at least one obedience scenario and one resistance scenario. After presenting a scenario to the class, the “audience” can suggest if they think that scenario calls for obedience or resistance. If there are scenarios where the class does not agree about the appropriate course of action, give students the opportunity to explain their positions and to listen to the ideas of others. This also could be structured as a barometer activity. After this exercises, students can determine the criteria they might use to evaluate when it is acceptable or unacceptable to obey authority or conform to the norms of the group. Groups can present their criteria to the class verbally. Or they can record their criteria on a poster, put their posters on the wall, and do a gallery walk of the room. A final activity might ask students to determine their own “obedience and conformity criteria,” drawing on the ideas from the various posters. Assessment ideas (for class work and/or homework) Any of the journal prompts or discussion questions included in this lesson idea could be used as the basis for formal or informal essay writing. Students can demonstrate their understanding of conformity and obedience by responding to the question, “Define obedience and conformity. How are they similar? How are they different?” Or you might ask students to synthesize their understanding of conformity, propaganda and obedience in Nazi Germany by addressing the following prompt: This section focused on the themes of obedience, conformity and propaganda. For each of these terms, do the following: 1) Define the term in your own words, 2) Identify at least two specific examples of how this concept played out in Nazi Germany, 3) Explain how the concept relates to experiences in your own life, and 4 )List one question that you have related to this concept. Encourage students to use their journals to help them with this assignment. Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION