Ben & Jerry`s - the Babson College Faculty Web Server

127C98a

COLLEGE

Ben & Jerry’s (A)

To do values-led sourcing well, you have to consider three factors. One is the business concern. One is the environmental concern. And one is the social mission. What we’ve learned is that if a supplier has a great social mission but can’t deliver the business value, the model won’t work long-term. What you are setting up is a dependent system. It’s a false transfer of wealth. The supplier isn’t really delivering the service you need, so they can’t get other customers. You’re paying them for something they can’t get anyone else to buy. Even if the supplier’s product is viable on the open market, if you’re too high a percentage of their output, you really aren’t doing them a favor. We encourage our suppliers to diversify their customer base, especially because our product demand has so much fluctuation.

1

-- Debra Heintz-Parente, Director of Materials, Ben & Jerry's

Introduction

In 1963, Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield were the two chubbiest and least athletic kids in

7 th

grade at Merrick, Long Island, New York. Their love of food brought them together and they became lifelong friends. However, they could not figure out what to do with their careers.

Realizing that they did not want to work for someone else; they decided to go into the food business since eating was their greatest passion. Bagel-making equipment was too expensive

($40,000), so they picked ice cream. They found a $5 ice-cream-making correspondence course offered by Penn State University and started out on the path to becoming ice cream moguls.

They knew college students ate a lot of ice cream and so they investigated most warm climate college towns, to see if they had a homemade ice cream parlor. They ultimately threw out the temperature criteria (all the warm climate cities already had a homemade ice cream outlet) and landed in Burlington, VT, where there was no competition. With a $12,000 investment ($4,000 of it borrowed), Ben and Jerry renovated an abandoned gas station in downtown Burlington and opened Ben & Jerry’s Homemade Ice Cream scoop shop, on May 5,

1978.

2

Today, Ben & Jerry's Homemade Ice Cream is a publicly traded (stock symbol: BJICA) frozen dessert company that manufactures and distributes super-premium ice cream, low fat ice cream, frozen yogurt and sorbet products in all 50 states and has over 160 franchised "scoop shops" in 20 states. The company employs 700 people and has international operations in Israel,

1 Ben & Jerry’s Double Dip , How to run a values-led business and make money, too , by Ben Cohen and Jerry

Greenfield, Simon & Schuster, 1997, p. 73.

2 Ben & Jerry’s: The Inside Scoop , by Fred “Chico” Lager, Crown Publishers, New York, 1994, p.13.

Professors James Hunt, Jay Rao, Richard Bliss, Michael Fetters, Carol Fiske, and Carl Gwin of Babson College, prepared this case as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation.

All information has been obtained from publicly available sources. Copyright © Babson College 1998

Canada, United Kingdom, Japan, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. In 1996, net sales exceeded $167 million

3

(See Exhibit 1).

However, business success was not enough by itself, particularly for Ben. In 1988, Ben,

Jerry, members of their Board of Directors and their senior managers, formally began the complex task of trying to operate a business that is both profitable and socially responsible.

Together they created a Mission Statement that survives to this day (See Exhibit 2). Ben &

Jerry’s contributes 7.5% of pretax profits to philanthropic activities.

Concocting Zany Flavors

In the beginning we simply made the highest quality ice cream we could. We like ice cream with chunks in it – pieces of Oreo, Heath Bars, nuts, candies. The original person we satisfied was Ben. At the same time, he couldn’t taste very well. So, I made the ice cream and he tasted it and I had to keep adding flavor till he knew what it was. He was the taste buds of the company.

4

-- Jerry Greenfield, Founder, Ben & Jerry’s

Ben and Jerry set out to make an ice cream that was rich, creamy, smooth, dense, and chewy. With 17-25% overrun,

5

Ben & Jerry’s ice cream and yogurts were heavier, creamier and richer than most ice cream brands. Today at Ben & Jerry’s, alchemists, flavor developers and ice cream therapists (not scientists) are responsible for mixing and blending ingredients. They develop over 100 prototype flavors every year, with a majority of them failing to reach the production line because the processors cannot handle mass production of some of the chunky, chewy, gummy add-ins.

Customers’ suggestions, especially for ingredients, are used in the product development process. The idea for “Cherry Garcia” in honor of Jerry Garcia, the lead guitarist of the Grateful

Dead, came via an anonymous postcard from two “Dead heads” in Portland, Maine.

6

Another customer, Susan Aprill, suggested “Chunky Monkey”, a concoction sounding like – banana

(monkey) with nuts and hunks of chocolate (chunks). “Chubby Hubby” – a vanilla malt ice cream with a fudge swirl, a peanut butter swirl, and chocolate-covered peanut-butter-filled pretzels – was suggested by a customer as well.

7

In the company’s early years, Jerry answered all the mail by himself. “I was the person making the ice cream, so I figured they were writing to me personally,” he used to say 8

. By

1986, they were getting letters by the sack, so Alice Blachly was hired. Her only job was to respond to customers. Each incoming letter received a handcrafted reply. Today, Alice has three more letter writers to assist her in responding to the nearly 20,000 letters, faxes, emails and voice mails they receive each year. They also do feedback tracking of customer comments (Exhibit 3) to production and R&D. Each pint container comes with a control number (Exhibit 4).

Customers are encouraged to enclose this control number along with their complaints and comments.

3 Ben & Jerry's Annual Report, 1997.

4 "What’s the scoop on Ben & Jerry?" Direct Marketing , Aug. 1994, v57, n4.

5 S ee the

" Note on the U.S. Ice Cream and Frozen Dessert Industry ", Babson College, Industry Note 127-N98, for definitions of industry terms.

6 Ben & Jerry’s: The Inside Scoop, p157.

7 Mitch Curren, PR Info Queen & Research Relationist, Personal Interview, August 25, 1998.

8 Ben & Jerry’s: The Inside Scoop, p157.

2

The R&D process represented a significant opportunity for Ben & Jerry’s to pursue their newly created company mission. At their 1988 annual meeting, shareholders criticized the management for using Oreo cookies because they are made by Nabisco, which is owned by R. J.

Reynolds. The shareholders didn’t like doing business with a tobacco company. The cookies were re-sourced and the flavor name was changed to Mint Chocolate Cookie.

9

Buying the Right Stuff, from the Right Sources

Cost of Goods. That’s the big lever. Ben & Jerry’s spends $90 million a year in packaging and ingredients. If we can spend a major portion of that in ways that benefit the community, we’ll accomplish a lot more than we can with philanthropy.

10

-- Ben Cohen, Founder, Ben & Jerry’s

The leadership of Ben & Jerry's has always had a sense of gratitude for support they receive from their customers. The initial results of this gratitude showed in their tendency to find excuses to give away ice cream, even at the expense of their ability to make a profit. Their sense of connection with the state of Vermont, as a community, helped to promote their interest in preserving Vermont family farms (suppliers of their raw materials) by providing a market for their dairy products. The farms were losing out competitively because of overproduction of milk in the rest of the country, low government floor prices, and the dominance of corporate megadairies using federally subsidized water in the Southwest.

Vermont dairy farmers represented the values that both Ben and Jerry believed in: small farms as opposed to bottom line driven corporate agribusiness; cows grazing on farm pastures as opposed to cows tied in barns all day and fed large amounts of drugs to combat disease and increase milk production. In 1991, the price of milk dropped tremendously forcing the farmers to sell below their cost of production. Most buyers pocketed the increased profits; except Ben &

Jerry’s. The board of directors decided to pay the same amount for milk that they had paid the year before. That meant nearly $500,000 less to Ben & Jerry’s bottom line. The company's view was that “this year’s milk isn’t worth any less to us than last year’s.” 11

This symbiotic relationship with the Vermont dairy farmer suppliers who have worked closely with Ben & Jerry’s from day one can pay off. In 1995, when Ben & Jerry’s was building its St. Albans plant, they desperately needed extra manufacturing space. The St. Albans co-op, one of its key milk suppliers, gave rent-free space in their building to set up a temporary manufacturing line, until their new plant was fully functional. Without this help, Ben & Jerry’s would not have been able to meet demand and would have lost business.

I’d be lying if I said it’s no extra trouble to do values-led sourcing. But one of the most powerful ways that Ben & Jerry’s can influence the world is through our purchasing power. We’re talking about $90 million a year of spending. That’s worth some extra work up front.

12

-- Debra Heintz-Parente, Director of Materials, Ben & Jerry's

9 Ben & Jerry’s: Double Dip, p 83.

10 ibid., p 55.

11 ibid., p 58.

12 Ben & Jerry’s Double Dip , p 63.

3

Some suppliers that might be desirable from the perspective of the company's social mission are not up to the task of providing either the quality or quantity of products needed by a large business such as Ben & Jerry's. One example of such a challenge involved Greyston

Bakery of Yonkers, New York. Ben had to invest considerable time and energy helping

Greyston qualify as a supplier. It was owned by a non-profit religious institution whose purpose was to train and hire unemployed or otherwise disadvantaged people. Greyston almost went out of business when it was unable to make a brownie ingredient that was good enough, in sufficient quantities, to meet Ben & Jerry's needs.

The first order was a couple of tons. That was a small order for Ben & Jerry’s, but huge for Greyston. Their system broke down. The brownies were coming off the line too fast and ended up being packed hot. They then were frozen. By the time it reached Ben & Jerry’s they had turned into fifty-pound blocks of brownie. Ben & Jerry’s production people wanted to pack it up and send it back. If they had done that Greyston could not have met its payroll the next day. Ben & Jerry’s production staff had to work overtime to break-up all the brownies.

Company staff kept going back and forth with Greyston, trying to get the brownies right. The explanation that this was an exception for this supplier was not well received by the production people and they were outraged. Working with Greyston didn’t seem socially beneficial to Ben &

Jerry’s workers.

13

Tensions were eased when Ben & Jerry’s had its employees visit Greyston and see first-hand what it was like to work there. The process of collaboration between the two companies moved forward with the result that now Greyston is a solid supplier of Ben & Jerry’s.

Out of this effort, a new flavor – Chocolate Fudge Brownie – was introduced that used the brownie pieces when the brownie blocks were broken.

Not all values-led purchases have been successes. Rev. James Carter of Howell

Township, New Jersey, ran a bakery called La Soul that was staffed with recovering alcoholics and drug addicts. In 1993, Ben & Jerry’s started buying piecrust and “goo” from La Soul for its

Low-Fat Apple Pie frozen yogurt. That year, the bakery sold some $1.5 million of crust and goo.

It received technical and financial support from Ben & Jerry’s as well. But the Apple Pie Frozen

Yogurt flopped and the orders stopped, leaving La Soul $500,000 in debt and its employees jobless. La Soul sued Ben & Jerry’s.

14

In response to media criticism for this and other failures, Ben stated: “No business that attempts to redefine the social and environmental role of business is going to have an easy time of it. The issues of social justice and commerce are complex. This does not mean we should not keep trying. We’ve made mistakes and plan on making a lot more.” 15

Making Ice Cream the Right Way

For a brief overview of the ice cream manufacturing process, please refer to “ Note on the

U.S. Ice Cream and Frozen Dessert Industry

”, Babson College, Industry Note 127-N98.

All of Ben & Jerry’s production is done at their 3 plants in Vermont – Waterbury,

Springfield and St. Albans.

16 Ben & Jerry’s low overrun, high butterfat, gooey swirls, chunky-

13 Ibid.

, p 60.

14 “Ben & Jerry’s: Corporate Orge,” Fortune , July 10, 1995

15 “At Ben & Jerry’s, social agenda churns with ice cream,” Knight-Ridder/Tribune Business News , Nov. 12, 1995

16 Ben & Jerry's Ice Cream was forced to manufacture outside Vermont in 1994, due to growing demand for product and their inability to meet that demand from their existing capacity in Vermont, prior to the opening of the St.

4

ingredient-filled ice creams require special equipment and handling. In addition to using modified special machinery to mix large chunks, the company has designed proprietary processes for swirling variegates (dessert sauces) into its finished products. All its plants are equipped with the latest in technology and efficiency. The company developed these capabilities by using and adapting a lot of their older equipment to improve operations. Many of these improvements came directly from the production floor staff. Some of Ben & Jerry’s veteran production staff is now in R&D. Through years of experience on the production floor they now know the capabilities and limitations of the machines. This helps in the design and development of new flavors that can be brought to mass production with few start-up problems. Ben & Jerry’s employees are proud of their accomplishments and eagerly talk about them.

For instance, it’s now famous Chocolate Chip Cookie Dough ice cream was originally sold in bulk only at scoop shops and did not come in pints. Automatic pint filling turned out to be a nightmare. Cookie dough swirls had to be mixed into the ice cream when it was cold. If it got soft, it would bind up the feeder and there would be ice-cream explosions flying all over the place. There were no existing machines to buy. Groups of people tried to get the dough into the ice cream by trying to keep the dough cold. Finally, a feeder task force was put in place and the people who worked with the machine every day were put on the task force. It took them almost

5 years to retrofit the feeder machine and successfully bring out the Chocolate Chip Cookie

Dough ice cream in pints.

In 1985, when Ben & Jerry’s moved into its plant in Waterbury, it was limited in the amount of wastewater that it could discharge into the municipal treatment plant. As sales and production skyrocketed, so did their wastewater, most of which was milky water. Ben & Jerry’s made a deal with Earl, a local pig farmer, to feed the milky water to his pigs. Earl’s pigs alone could not handle Ben & Jerry’s volume, so eventually they loaned Earl $10,000 to buy 200 piglets.

Once we did the pigs thing, we started to think way “out-of-the-box”.

17

-- Mitch Curren, PR Info Queen & Research Relationist, Ben & Jerry’s

The company’s experiences with TQM (Total Quality Management) were mixed with reactions varying from person to person, depending upon who is asked.

Back during our big failed TQM effort, we were trying to fit into a mold and we couldn’t. It was too rigid. We even tried to soften it and make it Ben & Jerry’s style. We were already using the tenets of TQM anyway and it became overkill.

Some of the PDCA [Plan, Do, Check, Act] was done during regular conversation.

Only now, we were over-communicating.

18

-- Mitch Curren, PR Info Queen & Research Relationist, Ben & Jerry's

TQM was very successful in some places. Like in manufacturing. Some of the

PDCA did work well. They [management] took it away from us because we were making all the decisions and the management was very afraid of that. Managers were leaving. There was upheaval. The new management was not taught this

Albans plant. They contracted for additional capacity from Edy's, of Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Source: Ben & Jerry’s

1996 10-K filing.

17 Personal interview, August 25, 1998

18 Personal interview, August 25, 1998.

5

TQM stuff and they did not know what was going on, and simultaneously, we were feeling good about ourselves because of all the empowerment.

19

-- Steve Hebert, Waterbury plant, Ben & Jerry's

As Exhibit 5 chronicles, Ben & Jerry's was facing increasingly difficult management tasks as it tried to develop more sophisticated systems to help manage growth, and achieve it’s goals. It’s organizational culture and management staff seemed more competent in the development of creative new products and novel marketing strategies, than with the detail oriented work of meshing people and operations effectively. One symptom of their managerial difficulties was their rate of on the job accidents and other illnesses (Exhibit 6). Its 1997 Annual

Report stated that the rate of injuries of workers trended downward in 1997. However, the rate was still higher than the industry average.

20

Nevertheless, it has continued to carefully monitor product quality. The Quality Control

Lab at each plant conducts tests to make sure the ice cream meets their standards. As pints come off the line, all are weighed and stamped with a control number indicating the plant number, production line, product SKU, batch number and time (Exhibit 4). Prior to packaging, sample pints are pulled off every half-hour and are cut in quarters or melted down to check for chunk amounts, chunk dispersal and consistent distribution of variegate patterns. The results of the tests are logged against the control numbers.

Ben & Jerry's has been attempting to address a number of environmental concerns related to its operations, as well. Conversion to more environmentally friendly pint packaging is it’s #1 priority in this area. Paperboard currently used in all Ben & Jerry’s pints (as well as by the industry as a whole) is coated with polyethylene that renders it non-compostable. The pints are also whitened using a chlorine bleaching process that produces a family of hazardous compounds, including dioxins, which are released into the environment.

Distribution

In September 1998, angered by an unwanted takeover offer from Dreyer’s Grand Ice

Cream Inc., and worried that it will lose control over its own fate, Ben & Jerry’s decided to end their 12-year old distribution relationship. Ben & Jerry's distribution agreement with Dreyer’s had gradually evolved to the point at which Dreyer's controlled 70% of Ben & Jerry’s distribution. Dreyer’s is known for its unusually good distribution system, in which its employees deliver and stock store freezers rather than rely on third-party wholesalers. However,

Ben & Jerry’s is planning on increasing its own field sales force by 50% and forging a new alliance with Diageo PLC’s Haagen-Dazs – until now regarded as an arch-competitor – to deliver its products. This new system is meant to get better control over retail selling prices and get its products into more small stores, and forge relationships with retailers that will help launch new products.

21

Apart from Dreyer’s, Ben & Jerry’s distribution hinges on nearly 300 other distributors and co-distributors.

We want them to take good care of our products and have a passion for it.

Running a distribution of frozen product, and especially ice cream, is about

19 Personal interview, August 25, 1998.

20 Ben & Jerry's 1997 Annual Report , p. 17.

21 “Ben & Jerry’s to End Relationship With Dreyer’s After Takeover Bid,” The Wall Street Journal , Sept., 1, 1998.

6

knowing how to handle the products. That is why we spend so much time trying to get to know the distributors well and do such silly things as riding their trucks. It is all about taking the extra care so that a customer does not bite into a pint that is icy. The constant challenge is managing all of them and align ourselves with the ones that can take care of our products well. The biggest percentage of product complaints we get is people finding icy crystallization in their pints. We give them their money back even though it is not our fault.

22

-- Mitch Curren, PR Info Queen & Research Relationist, Ben & Jerry's

Leadership, Social Responsibility, and Growth

Trying to integrate social responsibility with day to day business decision making adds another level of complexity to the task of running a company such as Ben & Jerry's. Ben, with

Jerry's support and the help of Jeff Furman (a Board member and business mentor from the early days of the company), has continued to be the visionary leader of this effort. This, at times, has left the operational managers of the business struggling to keep up.

In the early stages of its development, Ben & Jerry's was simply an ice cream business.

While both Ben and Jerry had had an interest in a variety of social causes during their late teens and early twenty's, once their own business was underway, they focused on making it successful.

They understood, for instance, that sometimes it was necessary to fire a worker if she or he wasn't able to get the hang of scooping the right amount into the cone or dish, quickly enough.

Ben would signal his having reached the conclusion that the offending party must go by signaling to Jerry: "The Monster is hungry. The Monster must eat."

23

Jerry, actually had the responsibility to do the firing.

In the early 1980's, both Ben and Jerry felt themselves becoming 'burned out' from struggling to keep their business heads above water and working 16 hour days. Worse, from their perspective, they saw themselves becoming "business people," just like the business people they had grown to instinctively distrust from their upbringing in the 1960's. They feared that leading a successful business required them to exploit others, for example, always going with the low cost supplier, even though such a decision might seem morally wrong. The public stock offering in 1985, and accompanying scrutiny from the business press, intensified these feelings.

Jerry began at that point to pull back from the business, even selling a substantial portion of his ownership (he did retain 10% of outstanding shares). He would subsequently move to Arizona and marry. However, since the late 1980's, he has been fully involved in the business again and has returned to Vermont.

Ben also contemplated leaving, feeling that there was nothing special about what he and

Jerry had accomplished. His course seemed set until a friend, Maurice Purpora, a local entrepreneur interested in social causes, convinced him otherwise. Purpora argued that "there was nothing to keep Ben from redefining the business so that it was consistent with his personal values, even if they didn't conform with traditional notions of how a business should be run."

24

He chided Ben to find a way to run the business so that it would become an actual expression of his progressive social beliefs.

22 Personal interview, August 25, 1998.

23 Ben & Jerry's Double Dip , p. 164.

24 Ibid.

, p. 57.

7

Ben took to the challenge with vigor and ultimately became the personal embodiment of the social mission of the company, as well as its marketing guru. Unfortunately, it became clear with his decision to stay in the business that neither he nor Jerry had been very effective at handling the duties required for effective management of a growing firm. Their business success resulted in an average growth rate of almost 60% per annum between the years of 1985 and

1989. Ben was not particularly skilled in finance, managerial accounting, operations management, or human resource management. Ben and Jerry realized rather quickly that they needed someone who did have those skills to manage the firm.

The first defacto chief operating officer of the firm was Fred "Chico" Lager. (Titles were rather informal and fluid during Ben & Jerry's early years.) Chico had had experience with several businesses including a restaurant/bar and entertainment venture. Just as importantly, he could accept Ben's growing interest in a social mission, love of product quality, and desire to grow the business. Ben, and subsequently their formal Board of Directors, gave Chico the responsibility for running the business operation, while Ben promoted the social mission and developed new products.

25

However, with this "split" between leadership of the mission and management of the business operations of the firm, the company began a long term "struggle" to develop harmony between the two. A typical, and visible, aspect of this struggle has been over a most basic question of human resource management: how to hire and reward the right people.

Ben has pushed the idea of hiring for values to varying degrees for the past decade, provoking strong opposition, even from Jerry. A Ben and Jerry dialogue from Double-Dip illustrates this tension:

26

Jerry: I'm sure there are people at Ben & Jerry's who disagree wholeheartedly with what we believe and what we do. And that's Okay, as long as they are doing their jobs.

Ben: How far would you take that idea? What if an employee is bad-mouthing gays, or people of color?

Jerry: It's a value of the company that we don't support that. While you're at work you can't bad-mouth any group of people.

Ben: I guess it's true - we don't control your whole life. Go home and badmouth gays or people of color, but not while you're in our workplace.

Jerry: We don't control your beliefs. It's your job performance, which incorporates the economic, quality and social missions. And that's all we have the right to comment on.

The dilemma involves several issues. First, how are jobs defined? Are jobs defined in a fashion that requires that employees accept the social mission of the company? Second, what is the impact of such an intense, top-down, leadership style? Ben has been criticized for pushing his values-based agenda too hard, rather than taking a more educational approach and trying to

'sell' his agenda to employees and others. Finally, can the rapidly growing company find good

25 Ben & Jerry's: The Inside Scoop , p. 180- 200.

26 Ben & Jerry's Double-Dip , p. 187.

8

managers? Will they overlook a potentially outstanding business manager because she or he has a different set of values from the founders?

Most employees (more than 85% in the yearly surveys of employee morale) state that they support the social mission and like working at Ben & Jerry's. Many employees are drawn to work at Ben & Jerry's because of the mission. Others find it compatible with their beliefs even though they may be more interested in other aspects of the business than the mission itself. The most significant complaints that employees voice about working at Ben & Jerry's have to do with what could only be seen as failures of basic business management. Employees feel confused about their roles, complain of a lack of interdepartmental communications, can't see reasonable career paths and don't receive the necessary training and development, for instance. Their problems with the implementation of Total Quality Management (Exhibit 5) are a reflection of such problems.

Ben & Jerry's Board of Directors is quite open about these difficulties, and has struggled with the problem of trying to professionalize its management for a number of years. Typically, a growing company would look to experienced managers, often from the outside, to help it develop and implement the necessary systems and processes to manage growth. (The complexity of Ben & Jerry's organization can be seen in Exhibit 7.) Its need to do so, however, has run squarely up against the question: how much do you pay professional managers?

Ben and Jerry were very aware of the growing criticism of corporate executives whose salaries and other forms of compensation are many, many multiples of those who actually make and deliver the product. In 1988, as they were refining their mission statement, Ben & Jerry's with their Board of Directors, set a standard for executive compensation in which the highest paid professional would make no more than five times the lowest paid plant employee. Their intent was not to limit higher levels of compensation but rather to raise everyone's salary.

Executives could earn as much as they wanted as long as the salaries for the lowest paid were no less than 20% of theirs. The 1:5 plan, pushed particularly by Ben, was the subject of intense debate within the company. Chico Lager, responsible for running the plants, felt like there were too many problems to solve with too few professional managers in the company to do so. The problem was becoming worse with the company's continued yearly growth. He argued that the

1:5 plan made it impossible to attract the right people to the company.

27

They searched for years for a Chief Financial Officer (CFO) but could not find anyone willing to take the position. Ultimately, they turned to someone from within the company who seemed to have the talent. They then helped her to develop into the role with the aid of an outside consultant.

Perhaps more importantly, they have had difficulty in recent years keeping the position of

CEO filled, as the Board tries to continue the process of professionalizing the management of the firm. Since 1990, the following executives have occupied the position of President or President and CEO (really the chief professional manager but second in command to Ben who currently serves as Chairman of the Board).

February 1989: Fred Lager is named president and chief executive officer, succeeding Ben Cohen, who retained, at that time, the position of co-

27 Ben & Jerry's Inside Scoop, p. 193-195.

9

Chairman of the Board of Directors with Jerry.

28

Lager was planning his own departure from Ben & Jerry's at this point, and one of his tasks was to provide time for him to mentor a successor, Chuck Lacey.

December 1990: Fred Lager departs, Chuck Lacey who had been groomed as a potential successor for several years, steps up to the position of

President.

29 Lacey had had some managerial experience in the health care industry before coming to Ben & Jerry's, and had served as chief operating officer before moving up to the role of President. Lacey's title did not include that of chief executive office. Ben Cohen carried the title of CEO.

June 1994: The company begins the search for a new CEO to replace Ben and culminating in a nationwide essay contest for potential replacements. Ben

& Jerry's had hoped to avoid the need to use an executive recruiter.

February 1995: Ben Holland, a former consultant from McKinsey, is hired as

President and CEO of Ben & Jerry's Ice Cream. On the day of the announcement, the company also announces that Chuck Lacey, who had held the title of President, was leaving. There is speculation that he was largely blamed for Ben & Jerry's lackluster financial performance.

30

Mr.

Holland was located with the assistance of an executive recruiter. Known as a "turn around" artist, he had been at the helm of several companies prior to coming to Ben & Jerry's. He plans to push into overseas markets as well as provide more effective management of plant operations. His value system is very consistent with that of the founders, and he has had experience in a variety of not-for-profit activities in addition to his business career.

31

September 1996: Ben Holland leaves the company, with one month's notice. Ben

& Jerry's Board of Directors launches another search with the help of an executive recruiter. Reasons for Holland’s departure included disputes with the founders, continued lackluster financial performance, and eroding market share in supermarkets. Additionally, his plans to move the company into the French marketplace were a source of tension with the founders because of France's tests of nuclear weapons.

32

January 1997: Perry Odak, a marketing specialist, accepts the position of CEO.

He is chosen for his marketing expertise, as well as his social values. He had held positions in a variety of companies, including Atari. His appointment is the subject of controversy because of his most recent job as a senior manager with U.S. Repeating Arms Co., the maker of Winchester

Rifles.

33

He is still CEO of Ben & Jerry's as of September 1998.

34

28 Wall Street Journal , February 28, 1989.

29 Ben & Jerry's Inside Scoop, p 204-212 .

30 Wall Street Journal , February 2, 1995.

31 Ibid., February 2, 1995.

32 Ibid., September 30, 1996.

33 Ibid., January 3, 1997.

34 Ben & Jerry's Web Site, http://www.benjerry.com, Ben & Jerry's Timeline.

10

In 1995, the salary ratio moved to 1:18, at which it currently stands. At the same time,

Ben & Jerry's developed an aggressive benefits policy which employees found very helpful.

They were named as one of the "one hundred best companies for working mothers" by Working

Mother magazine in 1994, 95, and 96.

35

The Future

As the United States’ population ages and becomes more health conscious, the industry is scrambling to provide low- or no-fat alternatives such as low fat ice cream, sorbet and frozen yogurt. While the low-fat healthy frozen desserts are here to stay, 1998 saw a surge in superpremium sales and the low-fat and yogurt lines were declining. For the first time there was a shortage in butterfat supply. According to Mary Lou Kelly, director of product marketing for

Ben & Jerry’s, “consumers are smart and they’re getting smarter. They understand fat, they understand calories, they understand the consequences of everything they eat. The bottom line is they’re looking for taste and innovative flavors. They are looking for fun and they’re looking for a treat. That’s what’s brought a lot of people back to ice cream.” 36

The one thing that people are still screaming for is sugar-free ice cream and ice cream with sugar substitutes. We have tried for a while and we have decided against sugar substitutes. We have not found a natural one that mixes well for the tastes we wan.

37

-- Mitch Curren, PR Info Queen & Research Relationist, Ben & Jerry's Ice Cream

Ben & Jerry's meanwhile, is moving vigorously into the international market while continuing their program of dessert and flavor research and development. In 1998, the company plans to open markets in Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the United Arab Emirates.

38

It won't be easy, and is likely to further tax their ability to function as an effectively managed organization. The excerpts (Exhibit 8) from a recent article in the Economist highlights the concerns of some industry experts abroad. It remains to be seen how their values will interact with those of the rest of they world, as they push their mission forward.

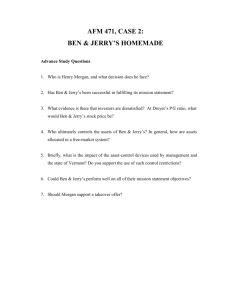

Discussion Questions

1.

What are the key characteristics of Ben & Jerry’s supply chain? How do their activities in the supply chain support their company mission?

2.

How would you recommend that Ben Cohen and the leadership of Ben & Jerry's work to mesh their business and social agenda? What do they need to do to exercise both aspects of their mission effectively?

3.

Analyze Ben & Jerry's financial performance during the period of rapid CEO Turnover.

Does this analysis shed any light on the issue of hiring the best available manager or hiring a manager whose social agenda is aligned with Ben & Jerry’s stated mission?

35 Ben & Jerry's Web Site, http://www.benjerry.com.

36 “Indulgence supreme,” Dairy Foods , March 1998, v99, n3.

37 Personal interview, August 25, 1998.

38 Ben & Jerry's Web Site, http://www.benjerry.com.

11

Exhibit 1: Ben & Jerry's Historical Financial Performance

(in 1000s )

1996 1995 1994

Net sales

Cost of sales

Gross profit

SG&A Expenses

Operating Income

Other Income (Expense)

Asset write-down

Pre-tax Income

Income taxes

Net income

Year-end Stock Price

Balance Sheet Data:

Working capital

Total assets

Long-term debt

Stockholders' equity

$ 167,155

$ 115,212

$ 51,943

$ 45,531

$ 6,412

$ (77)

$

$

$

$

6,335

2,409

3,926

11.75

$ 155,333

$ 109,125

$ 46,208

$ 36,362

$ 9,846

$ (441)

$

$

$

$

9,405

3,457

5,948

14.75

$ 148,802

$ 109,760

$ 39,042

$ 36,253

$ 2,789

$ 229

$ (6,779)

$ (3,761)

$ (1,893)

$ (1,868)

$ 11.50

$ 140,328

$ 100,210

$ 40,118

$ 28,270

$ 11,848

$ 197

$ 12,045

$ 4,845

$ 7,200

$ 15.75

1993 1992 1991

$ 131,969

$ 94,389

$ 37,580

$ 26,243

$ 11,337

$ (23)

$ 96,997

$ 68,500

$ 28,497

$ 21,264

$ 7,233

$ (729)

$ 11,314

$

$

$

4,639

6,675

25.25

$

$

$

$

6,504

2,765

3,739

19.25

$ 50,055

$ 136,665

$ 31,087

$ 82,685

$ 51,023

$ 131,074

$ 31,977

$ 78,531

$ 37,456

$ 120,295

$ 32,419

$ 72,502

$ 29,292

$ 106,361

$ 18,002

$ 74,262

$ 18,053

$ 88,207

$ 2,641

$ 66,760

$ 11,035

$ 43,056

$ 2,787

$ 26,269

Net sales

Cost of sales

Gross profit

SG&A Expenses

Operating Income

Other Income (Expense)

Asset write-down

Pre-tax Income

Income taxes

Net income

Year-end Stock Price

Balance Sheet Data:

Working capital

Total assets

Long-term debt

Stockholders' equity

1990 1989 1988

$ 77,024

$ 54,203

$ 22,821

$ 17,639

$ 5,182

$ (709)

$ 58,464

$ 41,660

$ 16,804

$ 13,009

$ 3,795

$ (362)

$ 47,561

$ 33,935

$ 13,626

$ 10,655

$ 2,971

$ (274)

$ 31,838

$ 22,673

$ 9,165

$ 6,774

$ 2,391

$ 305

1987 1986

$ 19,954

$ 14,144

$ 5,810

$ 4,101

$ 1,709

$ 208

1985

$ 9,858

$ 7,321

$ 2,537

$ 1,812

$ 725

$ (31)

$ 4,473

$ 1,864

$ 2,609

$ 8.00

$ 3,433

$ 1,380

$ 2,053

$ 7.50

$ 2,697

$ 1,079

$ 1,618

$ 7.75

$ 2,696

$ 1,251

$ 1,445

$ 7.25

$ 1,917

$ 901

$ 1,016

$ 4.50

$ 694

$ 143

$ 551

$ 5.00

$ 8,202

$ 34,299

$ 8,948

$ 16,101

$ 5,829

$ 28,139

$ 9,328

$ 13,405

$ 5,614

$ 26,307

$ 9,670

$ 11,245

$ 3,902

$ 20,160

$ 8,330

$ 9,231

$ 3,678

$ 12,805

$ 2,442

$ 7,758

$ 4,955

$ 11,076

$ 2,582

$ 6,683

12

Exhibit 2: Ben & Jerry's Mission Statement

BEN & JERRY'S IS DEDICATED TO the creation & demonstration of a new corporate concept of linked prosperity. Our mission consists of three interrelated parts.

UNDERLYING THE MISSION is the determination to seek new and creative ways of addressing all three parts, while holding a deep respect for individuals inside and outside the company, and for the communities of which they are a part.

Product

To make, distribute and sell the finest quality all natural ice cream and related products in a wide variety of innovative flavors made from Vermont dairy products.

Economic

To operate the Company on a sound financial basis of profitable growth, increasing value for our shareholders, and creating career opportunities and financial rewards for our employees.

Social

To operate the Company in a way that actively recognizes the central role that business plays in the structure of society by initiating innovative ways to improve the quality of life of a broad community - local, national, and international.

Underlying the mission of Ben & Jerry's is the determination to seek new & creative ways of addressing all three parts, while holding a deep respect for individuals inside and outside the

Company and for the communities of which they are a part.

© Ben & Jerry's Homemade, Inc.

13

Exhibit 3: Customer Comments

Total Customer Contacts

Type of Comment

Fan with complaint

Fan

General Comments

Complaint only

Social Mission

Nutritional concerns

Inquiry only

1995

16,210

7,492

2,835

2,292

1,534

860

323

683

1996

16,111

7,582

3,284

2,346

1,434

635

376

366

Lost customers 191 88

(Source: Ben & Jerry’s 1996 and 1997 Annual Reports)

Exhibit 4: Quality Tracking Information

1997

19,761

8,761

4,673

2,988

1,164

895

677

527

76

14

Exhibit 5: Excerpts from “Getting It Right,” by Liz Bankowski, Crunch Time (company newsletter), April 4 1995

Amidst 37% growth in business, in 1992 Ben & Jerry’s embarked on an ambitious training program in Total Quality Management (TQM) that involved nearly a third of the company. In addition to focusing on attention to process and on always meeting customer needs, the training was intended to begin a transformation of how we worked. The “Ready, Fire, Aim” approach to problem solving was replaced with the

PDCA – “Plan, Do, Check, Act.” Instead of top-down decision making, problems were solved where they occurred. The traditional, hierarchical management structure would evolve to a team-based environment with the role of coach or team leader replacing the role of the manager.

Although they had some successes with team-based design, there were no clear business objectives provided at the start. The agenda for the Big Nine Teams was too ambitious and senior management skills were too shallow to pull it off. Teams were left to do the best they could to create their own mission and objectives. The learning curve for team members was too steep in attempting to solve big problems like safety, new product rollouts and designing a new plant. Expertise outside the teams was not sufficiently valued and “teamness” took precedence over results.

The TQM training was too removed from day to day application to change the overall environment. Few managers were involved and thus unfamiliar with the principles of

TQM. Coworkers came to resent the time away and their added workload. No one was seeing tangible results from the significant investment of resources.

15

Exhibit 6: Injury Incident Rates

25

20

15

10

35

30

Dairy Mfg.

Trucking, Distribution,

Warehousing

Retail Stores

Administration

5

0

1995 Ind. Avg.

1995 1996 1997

(Number of illnesses/injuries per 100 full-time workers)

(Note: Some 1995 Ben & Jerry’s figures are not available)

(Source: Ben & Jerry’s 1997 Annual Report)

Exhibit 7: Ben & Jerry's Organization

Board of Directors

Sr. Dir. Ops.

Bruce Bowman

Manufacturing

Operations

Retail

Operations

Reserach &

Development

Quality

Assurance

Natural

Resources

Materials &

Logistics

Sr. Dir. Soc. Mission

Liz Bankowski

Sr. Dir. Bus. Dev.

Angelo Pezzani

The Foundation International

Licensing

Legal

CEO

Perry Odak

Sr. Dir. HR

Richard Doran

Human

Resources

Organization

Development

Communications

(Internal)

Safety

Central

Facilities

CFO

Fran Rathke

Corporate

Controller

Treasury

Information

Systems

CMO

Larry Benders

Product

Marketing

Innovation

Communications

(External)

Design

Sr. Dir. Sales

Chuck Green

Regional

Management

Sales

Analysis

Vermont's

Finest

Food

Service

(Source: Mitch Curren, PR Info Queen & Research Relationist, Ben & Jerry’s)

16

Exhibit 8:

Excerpts from “Raspberry Rebels,” The Economist, Sept. 6, 1997, p 61

….Ben & Jerry’s will find it hard to grow much faster than the stagnant American market for ice cream. That suggests looking abroad, which could put still pressure on the firm to step away from its roots. One reason is that overseas expansion will not be easy. Haagen-Dazs is already present internationally. The brand has the advantage of the multinational marketing and distribution network of Grand Metropolitan. Haagen-Dazs is strong in several big markets outside

America, including Japan, whose 640,000 tonnes of annual ice cream consumption is the second largest in the world. By contrast, Ben & Jerry’s efforts outside North America have so far been haphazard. In 1986 a friend of Mr.

Cohen’s set up a Ben & Jerry’s shop in Israel. In 1992, Ben & Jerry’s set up a joint venture known as Iceverk in Karelia in Russia, which it walked away from in 1996, leaving the equipment that it had installed to its awkward local partners.

Another difficulty with being international is that Ben & Jerry’s idiosyncrasies risk translating badly in different parts of the world. In Europe strong advertising has established Haagen-Dazs in consumers’ mind as a sophisticated, sexy luxury.

Against this, Ben & Jerry’s zaniness can look goofy. Subsidizing schools in

French city slums or backing green projects may be generous and caring, but it hardly marks the company out as a bunch of fun-loving rebels. In some parts of

Asia, the notion that companies should help the local community is as conventional as raspberry ripple.

Some of the firm’s other virtues will also be worth less and cost more to international customers. Messrs. Cohen and Greenfield generously decided to support their neighbors on Vermont’s dairy farms by buying milk and cream exclusively from them. It was also a sensible commercial decision: Vermont cream has a good, wholesome reputation. Proclaiming on tubs that the ingredients come from Vermont is a selling point in New England. But the assertion resonates less with Californians, let alone Bavarians; while the tie to one corner of America raises transport costs. Haagen-Dazs, by contrast, is made in two places in the United States, as well as in Canada, France and Japan.

It is wrong to say that Ben & Jerry’s social mission is just a drag on its commercial aspirations: after all, some of its customers shell out the extra cash for

Rainforest Crunch precisely because it is chock full of righteously harvested nuts from tribal cooperatives in the Amazon. But the logic of commercial success and geographical expansion means that what started as a rebellion of sorts, risks becoming just another brand strategy. As Mr. Perry Odak (CEO of Ben &

Jerry’s) warned shareholders earlier this year, Ben & Jerry’s must beware “the inexorable drift and pull toward the mainstream.”

17