Light in August

advertisement

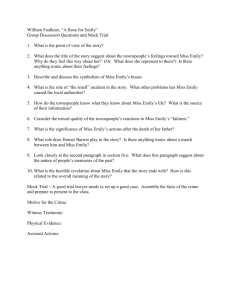

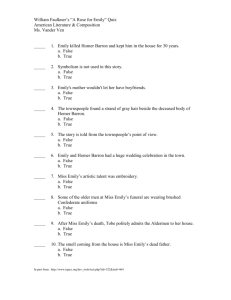

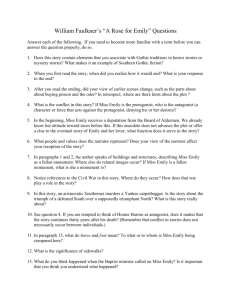

Brief Introduction about William Faulker William Faulkner(1897-1962):American novelist and short story writer best known for his Yoknapatawpha cycle, developed as a fable of the American South and of human destiny. Faulkner’s style is not very easy—in this he has much connections to European literary modernism. His sentences are long and hypnotic, sometimes he withholds important details or refers to people or events that the reader will not learn about until much later. After briefly attending the University of Mississippi, Faulkner worked as a bookshop assistant in NewYork and a journalist in New Orleans where he made friends with Sherwood Anderson, who helped him published Soldiers’ pay (1926), his first novel, about the homcoming of a fatelly wounded soldier, in the vein of the “lost generation.” It was followed by Mosquitoes(1927), a satirical portrait of Bohemian life, artist and intellectuals, in New Orleans. In 1929, Faulkner wrote Sartoris, the first novel in his long, loosely constructed Yoknapatawpha sage. Yoknapatawpha was a Chickasaw Indian term which meant “water passes slowly through flatlands.” In the same year, Faulkner published the Sound and the Fury, and established a solid reputation among critics. This novel is a study of the collapse of a proud Southern family, the Compsons. Faulkner told the sroty first through the eyes of an idiot, then through the eyes of two brothers-known as the multiple point of view technique. As I Lay Dying came out in 1930, which reveals the psychological relationships of a subnormal poor-white family on a pilgrimage to bury their mother. Like the Sound and the Fury , the novel has no single narrator. Instead, it has 15 narrators—family members and outsiders—who piece together a funeral journey in 59 unmembered sections. The result is a tour de force, a work of art that displays Faulkner’s incredible technical skill as a writer. Even more, incredible is the fact that he wrote it in just 47 days. In 1930, Faulkner began contributing short stories to national magazines.”A Rose for Emily” appeared in 1930 in Forum, one of the popular magazines. In 1931, Faulkner published Sanctuary. In this book,he ruturned to a more conventional way of presenting materal. He conceived of Sanctuary as a “pot-boiler”—a saleable mix of sex and violence. During the 1930s and the 1940s Faulkner wrote many of his finest books, including Light in August(1932), Absalom,Absalom!, The Wild Palms, The Hamlet, Go Down, Morses. By 1945, when his novels were out of print, Faulkner accepted a contract to write movie scripts in Hollywood. His second period od success bagan with the publication in 1946 of the Portable Faulkner, which presented his Yoknapatawpha legend as a whole. In 1948 Faulkner published another novel, Intruder In The Dust. Collected Stories, published in 1950, won the National Book Award. In 1949, for his literary accomplishments, Faulkner was awarded the Noble Prize for literature. In his acceptance speech, he explained that it is the writer’s duty and privilege”to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honour and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars, to help him endure and prevail.” His later books became didactic, however, often seeming to be mere echoes of his Noble Prize acceptance speech. In 1954 Faulkner’s longest novel, A Fable, on which he had been working for mearly 10 years, was published. Faulkner rounded out the Yoknapatawpha story with The Town and The Mansion. A Classic Short Fiction -- A Rose for Emily 1 When Miss Emily Grierson died, our whole town went to her funeral: the men through a sort of respectful affection for a fallen monument, the women mostly out of curiosity to see the inside of her house, whice no one save an old manservant—a combined gardener and cook—had seen in at least ten years. It was a big, squarish frame house that had once been white, decorated with cupolas and scrolled balconies in the heavily lightsome style of the seventies, set on what had once been our most select street. But garages and cotton gins had encroached and obliterated even the august names of that neighbourhood: only Miss Emily’s house was left, lifting its stubborn and coquettish decay above the cotton wagons and the gasoline pumps—an eyesore among eyesores. And now Miss Emily had gone to join the representatives of those august names where they lay in the cedar-bemused cemetery among the ranked and annoymous graves of Union and Confederate soldiers who fell at the battle of Jefferson. Alive, Miss Emily had been a tradition, a duty, and a care; a sort of hereditary obligation upon the town, dating from that day in 1894 when Colonel Sartoris, the mayor—he who fathered the edict that no Negro woman should appear on the streets without an apron—aemitted her taxes, the dispensation dating from the death of her father on into perpetuity. Not that Miss Emily would have accepted charity. Colonel Sartoris invented an involved tale to the effect that Miss Emily’s father had loaned money to the town, which the town, as a matter of business, preferred this way of repaying. Only a man of Colonel Sartoris’ generation, with its more modern ideas, bacame mayors and aldermen, this arrangement created some little dissatisfaction. On the first of the year they mailed her a tax notice. February came, and there was no reply. They wrote her a formal letter, asking her to call at the sheriff’s office at her convenience. A week later the mayor wrote her himself, offering to call or to send his car for her, and received in reply a note on paper of an archaic shape, in a thin, flowing calligraphy in faded ink, to the effect that she no longer went out at all. The tax notice was also enclosed, without comment. They called a special meeting of the Board of Aldermen. A deputation waited upon her, knocked at the door through which no visitor had passed since she ceased giving china-painting lessons eight or ten years earlier. They were admitted by the old Negro into a dim hall from which a stairway mounted into still more shadow. It smelled of dust and disuse—a close, dank smell. The Negro led them into the parlor. It was furnished in heavy, leather-covered furniture. When the Negro opened the blinds of window, they could see that the leather was cracked; and when thet sat down, a faint dust rose sluggishly about their thighs, spinning with slow motes in the single sun-ray. On a tarnished gilt easel before the fireplace stood a crayon portrait of Miss Emily’s father. They rose when she entered—a small, fat woman in black, with a thin gold chain descending to her waist and vanishing into her belt, leaning on an ebony cane with a tarnished gold head. Her skeleton was small and spare; perhas that was why what would have been merely plumpness in another was obesity in her. She looked bloated, like a body long submerged in motionless water, and of that pallid hue. Her eyes, lost in the fatty ridges of her face, looked like two small pieces of coal presses into a lump of dough as they moved from one face to another while the visitors stated their errand. She did not ask them to sit. She just stood in the door and listened quietly until the spokesman came to a stumbling halt. Then they could hear the invisible watch ticking at the end of the gold chain. Her voice was dry and cold. “I have no taxes in Jefferson. Colonel Sartoris explained it to me. Perhaps one of you can gain access to the city records and satisfy yourselves.” “But we have. We are the city authorities, Miss Emily. Didn’t you get a notice from the sheriff, signed by him?” “I received a paper, yes,”Miss Emily said.”perpahs he considers himself the sheriff...I have no taxes in Jefferson.” “But there is nothing on the books to show that, you see. We must go by the--” “See Colonel Sartoris. I have no taxes in Jefferson.” “But, Miss Emily--” “See Colonel Sartoris.”(Colonel Sartoris had been dead for almost ten years.) “I have no taxes in Jefferson. Tobe!” The Negro appeared. “Show these gentlemen out.” 2 So she vanquished them, horse and foot, just as she had vanquished their fathers thirty years before about the smell. That was two years after her father’s death and a shorttime after her sweetheart—the one we believed would marry her—had deserted her. Afterher father’s death she went out very little; after her sweetheart went away, people hardly saw her at all. A few of the ladies had the temerity to call, but were not received, and the only sign of life about the place was the Negro man—a young man then—going in and out with a market basket. “Just as if a man—any man—could keep a kitchen properly,” the ladies said; so they were not surprised when the smell developed. It was another link between the gross, teeming world and the high and mighty Griersons. A neighbour, a woman, complained to the mayor, Judge Stevens, eighty years old. “But what will you have me do about it, madam?” he said. “Why, send her word to stop it,” the woman said. “Isn’t there a law?” “I’m sure that won’t be necessary,” Judge Stevens said.”It’s probably just a snake or a rat that nigger of hers killed in the yard. I’ll speak to him about it.” The next day he received two more complaints, one from a man who came in diffident deprecation. “We really must do something about it, Judge. I’d be the last one in the world to bother Miss Emily, but we’ve got to do something.” That night the Board of Aldermen met—three gray—beards and one younger man, a member of the rising generation. “It’s simple enough,” he said. “Send her word to have her place cleaned up. Give her a certain time to do it in, and if she don’t...” “Dammit, sir,” Judge Stevens said, “will you accuse a lady to her face of smelling bad?” So the next night, after midnight, four men crossed Miss Emily’s lawn and slunk about the house like burglars, sniffing along the base of the brickwork and at the cellar openings while one of them performed a regular sowing motion with his hand out of a sack slung from his shoulder. They broke open the cellar door and sprinkled lime there, and in all the outbuildings. As they recrossed the lawn, a window that had been dark was lighted and Miss Emily sat in it, the light behind her, and her upfight torso motionless as that of an idol. They crept quietly across the lawn and into the shadow of the locusts that lined the streer. After a week or two the smell went away. That was when people had begun to feel really sorry for her. People in our town, remembering how old lady Wyatt, her great-aunt, had gone completely crazy at last, believed that the Griersons held themselves a little too high for what they really were. None of the young men were quite good enough for Miss Emily and such. We had long thought of them as a tableau, Miss Emily a slender figure in white in the background, her father a spradded silhouette in the foreground, his back to her and slutching a horsewhip, the two of them framed by the back-flung front door. So when she got to be thirty and was still single, we were not pleased exactly, but vindicated; even with insanity in the family she wouldn’t have turneddown all of her chances if they had really materialized. When her father died, it got about that the house was all that was left to her; and in a way, people were glad. At last they could pity Miss Emily. Being left alone, and a pauper, she had become humanized. Now she too would know the old thrill and the old despair of a penny more or less. The day after hisdeath all the ladies prepared to call at the house and offer condolence and aid, as is our custom. Miss Emily met them at the door, dressed as usual and with no trace of grief on her face. She told them that her father was not dead. She did that for three days, with the ministers calling on her, and the doctors, trying ro persuadeher to let them dispose of the body. Just as they were about to resort to law and force, she broke down, and they buried her father quickly. We did not say she was crazy then. We believed she had to do that. We remembered all the young men her father had driven away, and we knew that with nothing left,she would have to cling to that which had robbed her, as people will. 3 She was sick for a long time. When we saw her again, her hair was cut short, making her look like a girl, with a vague resemblance to those angels in colored church windows—sort of tragic and serene. The town had just let the contracts for paving the sidewalks, and in the summer after her father’s death they began the work. The construction company came with niggers and mules and machinery, and a foreman named Homer Barren, a Yankee—a big, dark, ready man, with a big voice and eyes lighter than his face. The little boys would follow in groups to hear him cuss the niggers, and the niggers singing in time to the rise and fall of picks. Pretty soon he knew everybody in town. Whenever you heard a lot of laughing anywhere about the square, Homer Barren would be in the center of the group. Presently we began to see him and Miss Emily on Sunday afternoons driving in the yellow-wheeled buggy and the matched team of bays from the livery stable. At first we were glad that Miss Emily would have an interest, because the ladies all said, “Of course a Grierson would not think seriouslyof a Northerner, a day laborer.” But there were still others, older people, who said that even grief could not cause a real lady to forget noblesse oblige—without calling it noblesse oblige. They just said, “Poor Emily. Her kinsfolk should come to her.” She had some kin in Alabama; but years ago her father hadfallen out with them over the estate of old lady Wyatt, the crazy, and there was no communication between the two families. They had not even been represented at the funeral. And as soon as the old people said,”Poor Emily,” the whispering began. “do you suppose it’s really so?” They said to one another. “Of course it is. What else could...” This behind their hands; rustling of craned silk and satinbehind jalousies closed up the sun of Sunday afternoon as the thin, swift clop-clop-clop of the matched team passes: “Poor Emily.” She carried her head high enough—even when we believed that she was fallen. It was as if she demanded more than ever the recognition of her dignity as the last Grierson; as if it had wanted that touch of earthiness to reaffirm her imperviousness. Like when she bought the rat poison, the arsenic. That was over a year after they had begun to say “Poor Emily,” and while the two female cousins were visiting her. “I want some poison,” she said to the druggist. She was over thirty then, still a slight woman, though thinner than usual, with cold, haughty black eyes in a face the flesh of which was strained across the temples and about the eye-sockets as you imagine a lighthouse-keeper’s face ought to look. “I want some poison,” she said. “Yes, Miss Emily. What kind? For rats and such? I’d recom--” “I want the best you have. I don’t care what kind.” The druggist named several. “They’ll kill anything up to an elephant. But what you want is--” “Arsenic,” Miss Emily said. “Is that a good one?” “Is ... arsenic? Yes, ma’am. But what you want--” “I want arsenic.” The druggist looked down at her. She looked back at him, erect, her face like a strained flag. “Why, of course,” the druggist said. “If that’s what you want. But the law requires you to tell what you are going to use it for.” Miss Emily just stared at him, her head titled back in order to look at him eye for eye, until he looked away and went and got the arsenic and wrapped it up. The Negro delivery boy brought her the package; the druggist didn’t come back. When she opened the package at home there was written on the box, under the skull and bones: “For rats.” 4 So the next day we all said, “She will kill herself”; and we said it would be the best thing. When she had first begun to be seen with Homer Barren, we had said, “She will marry him.” Then we said, “She will persuade him yet,” because Homer himself had remarked—he liked men, and it was known that he drank with the younger men in the Elks’ Club—that he was not a marring man. Later we said, “Poor Emily” behind the jalousies as they passed on Sunday afternoon in the glittering buggy, Miss Emily with her head high and Homer Barren with his hat cocked and a cigar in his teeth, reins and whip in a yellow glove. Then some of the ladies bagan to say that it was a disgrace to the town and a badexample to the young people. The men did not want to interfere, but at last the ladies forced the Baptist minister—Miss Emily’s people were Episcopal—to call upon her. He would never divulge what happened during that interview, but he refused to go back again. The next Sunday they again drove about the streets, and the following day the minister’s wife wrote to Miss Emily’s relations in Alabama. So she had blood-kin under roof again and we sat back to watch developments. At first nothing happened. Then we were sure that they were to be married. We learned that Miss Emily had been to the jeweler’s and ordered a man’s toilet set in silver, with the letters H.B. on each piece. Two days later we learned that she had bought a complete outfit of men’s clothing, including a nightshirt, and we said, “They are married.” We were really glad because the two female cousins were even more Grierson than Miss Emily had ever been. So we were not surprised when Homer Barren—the streets had been finished some since—was gone. We were a little disappointed that there was not a public blowing—off, but we believedthat he had gone on to prepare for Miss Emily’s coming, or to give her a chance to get fid of the cousins. (By that time it was a cabal, and we were all Miss Emily’s allies to help circumvent the cousins.) Sure enough, after another week they departed. And, as we had expected all along, within three days Homer Batten was back in town. A neighbor saw the Negro man asmit him at the kitchen door at dust one evening. And that was the last we saw Homer Barren. And Miss Emily for some time. The Negro man went in and out with the market basket, but the front door reminded closed. Now and then we would see her at a window for a moment, as the men did that night when they sprinkled the lime, but for almost six months she did not appear on the sreeets. Then we know that this was to be expected too; as if that quality of her father which had thwarted her woman’s life so many times had been too virulent and too furious to die. When we next saw Miss Emily, she had grown fat and her hair was turning gray. During the next few years it grew grayer and grayer until it attained an even pepper-and-salt iron-gray, when it ceased turning. Up to the day of her death at seventy-four it was still that vigorous iron-gray, like the hair of an active man. From that time on her front door remained closed, save for a period of six or seven years, when she was about forty, during which she gave lessons in china-painting. She fitted up a studio in one of the downstairs rooms, where the daughters and granddaughters of Colonel Sartoris’ contemporaries were sent to her with the same regularity and in the same sprit that they were sent to church on Sundays with a twenty-five-cent piece for the collection plate. Meanwhile her taxes had been remitted. Then the newer generations became the backbone and the sprit of the town, and the painting pupils grew up and fell away and did not send their children to her with boxes of color and tedious brushes and pictures cut from the ladies’ magazines. The front door closed upon the last one and remained closed for good.When the town got free postal delivery, Miss Emily alone refused to let them fasten the metal numbers above her door and attach a mailbox to it. She would not listen to them. Daily, monthly, yearly we watched the Negro grow grayer and more stooped, going in and out with the market basket. Each December we sent her a tax notice, which would be returned by the post office a week later, unclaimed. Now and then we would see her in one of the downstairs windows—she had evidently shut up the top floor of the house—like the craven torso of an idol in a niche, looking or not looking us, we could never tell which. Thus she passed from generation to generation—dear, inescapable, impervious, tranquil, and perverse. And so she died. Fell ill in the house filled with dust and shadows, with only a doddering Negro man to wait on her. We did not even know she was sick; we had long since given up trying to get any information from the Negro. He talked to no one, probably not even to her, for his voice had grown harsh and rusty, as if from disuse. She died in one of the downstairs rooms, in a heavy walnut bed with a curtain, her gray head propped on a pillow yellow and moldywith age and lack of sunlight. 5 The Negro met the first of the ladies at the front door and let them in, with their hushed, sibilant voices and their quick, curious glances, and then he disappeared. He walked right through the house and out the back and was not seen again. The two female cousins came at once. They held the funeral on the second day, with the town coming to look at Miss Emily beneath a mass of bought flowers, with the crayon face of her father musing profoundly above the bier and the ladies sibilant and macabre; and the very old men—some in their brushed Confederate uniforms—on the porch and the lawn, talking of Miss Emily as if she had been a contemporary of theirs, believing that they had danced with her and courted her perhaps, confusing time with its mathematical progression, as the old do, to whom all the past is not a diminishing road but, instead, a huge meadow which no winter ever quite touches, divided from them now by the narrow bottle-neck of the most recent decade of years. Already we knew that there was one room in that region above stairs which no one had seen in forty years, and which would have to be forced. They waited until Miss Emily was decently in the ground before they opened it. The violence of breaking down the door seemed to fill this room with pervading dust. A thin, acrid pall as of the tomb seemed to lie everywhere upon this room decked and furnished as for a bridal: upon the valance curtains of faded rose color, upon the rose-shadedlights, upon the dressing table, upon the delicate array of crystal and the man’s toilet things backed with tarnished silver, silver so tarnished that the monogram was obscured. Among them lay a collar and tie, as if they had just been removed, which, lifted, left upon the surface a pale crescent in the dust. Upon a chair hung the suit, carefully folded; beneath it the two mute shoes and the discarded socks. The man himself lay in the bed. For a long while we just stood there, looking down at the profound and fleshless grin. The body had apparently once lain in the attitude of an embrace, but now the long sleep that outlasts love, that conquers even the grimace of love, had cuckolded him. What was left of him, rotted beneath what was left of the night-shirt, had become inextricable from the bed in which he lay; and upon him and upon the pillow beside him lay that even coating of the patient and biding dust. Then we noticed that in the second pillow was the indentation of a head. One of us lifted something from it, and leaning forward, that faint and invisible dust dry and acrid in the nostrils, we saw a long strand of iron-gray hair. POLT SUMMARY A Rose for Emily is a classic story representing Faulker’s favorite subject, theme and style. The story begings with a funeral of the eponymous Mis Emily. It doesn’t follow a particular order of chronological time. The narration flows backwards of forwards in a line of reality, revealing signicant details of Emily’s life and the murder of the Homer Barron by Emily, which are suspected till the end of the story. The narrative is also divided into five parts, allowing for flexible shifts in time and displays of Emily’s image at various stages of her life. Through a story about Emily, the author tries to pinpoint an unavoidable fate of the aristocracy anf various changes in the South America after the Cicil War. TEXT ANALYSIS In striking contrast with most North American anthors, we find in Faulkner’s works, an almost universal sence of tightly knit and long established community. Diffused and anonymous though it be, the community is the field for man’s action and the norm by which his action is judged and regulated. Here, human behaviour is often determined more by social custom than by legal restraint. For example, when Miss Emily’s house begins to smell, it is the youngest alderman who wants to give Miss Emily offical notice to clean up her place. Judge Stevens, however, a gentleman of the old school, angrily denounces the plan. The conflict between them is not only growing generation against the old. The final decision to secretly lime the ground id clearly illegal, which proves again unoffical code behaviour is stronger than the force of law. Although a person’s ties to the community are important, Faulkner suggests that man must never let it become the solo arbiter of their values. In this fiction, keen awareness of the perils risked by the individual who attempts to run counter to the communter is also revealed. Doing so, the divergent individual may risk fanaticism, madness or martyrdom, just as Miss Emily’s final fanatiscism and absolute isolation. One of Faulkner’s chief thematic preoccupations is the past. He regards the past as a repository of great images of human effort and intergrity, and also as the source of a dynamic evil. He is aware of the romantic attraction of the past and realizes that submission to this romance of the past is a form of death. In A Rose for Emily, Faulkner contrasts the past with the present era. The past is represented in Emily herself, in Colonel Sartoris, in the old Negro servant, and in the Board of Alderman. Miss Emily Griersons is one of the numerous characters in Faulkner’s works who are warped by their inheritance from the past and who are cut off from the community—sometimes by their own will—to their detriment. In the story, Miss Emily is described as a “fallen monument”. She seems to be the product of an earlier era and surrounde herself with reminders of the past. When she dies, only her house was left, “lifting its stubborn and coquettish decay above the cotton wagons and the gasoline pumps—an eyesoreamong eyesores”. The house thus becomes a juxaposition of Emily herself. Emily’s embracing of her dead lover becomes a gruesome symbol of what happens then one is fettered to the past. Her face is compared to that of a lighthouse keeper—a person who necessarily lives in isolation from the people whom he protects and whose vessels he warns off the rocks and shoals. Her fanaticism and madness is in part a concequence of the injury done her by the fact of isolation, but it is also related to her pride. Pride can play an important role in the formation of one’s good character. But if it goes to the extreme, it will pile up obstacles in one’s contingency. In many respects Emily’s story characterises the whole of southern society at that time.The gloty of the South has gone with the end of the Cicil War. On the other hand, the present is expresswd chiefly through the words of the unnamed narrator. The new Board of Alderman, Homer Borron(the representative of Yankee attitude toward the Griersons and thus toward the South), and represent the present time period. This story is related by a member of the community who, though nameless, thinks of himself as representative of the townsfolk. The first sentence strikes this note: “When Miss Emily Grierson died, our whole town went to her funeral...” Throughout the story the anmeless narrator “we” keeps using such locutions as “At first we were glad ...” “So the next day we all said...” “We were glad because the two female cousins...” This nameless narrator “we” rather than “I”, suggest what Miss Emily’s history of madness and murder meant to the community, though “we” never put that meaning into a definition. First-person narrative enables the narrator to comver his own feelings and thoughts as well as report the action, and allows the reader to access to the mind of the narrator. Somebody complains Faulkner’s deliberate use of long convoluted sentence structure, which makes his his work extremely difficult to read. They are, actually, not gratuiously used, but essential to novel’s meaning, and their effect on the reader has been carefully calculated. In an interview, Faulkner said: “...to me, no man is himself, he is the sum of his past. There is no such thing really as “was” because the past is. It is a part of every man, every woman and every moment. All of his and her ancestry, background, is all a part of himself and herself at any moment. And so a man, a character in a story at any moment of action is not just himself as he is then, he is all that made him, and the long sentence is an attempt to get his past and possibly his future into the instant in which he does something...” In part 5, the sentences go like “The two female cousins came at once. They held the funeral on the second day, with the town coming to look at Miss Emily beneath a mass of bought flowers, with the crayon face of her father musing profoundly above the bier and the ladies sibilant and macabre; and the very old men—some in their brushed Confederate uniforms—on the porch and the lawn, talking of Mis Emily as if she had been a contemporary of theirs, believing that they had danced with her and courted her perhaps, confusing time with its mathematical progression, as the old do, to whom all the past is not a diminishing road but , instead, a huge meadow which no winter ever quite touches, divided from them now by the narrow bottle-neck of the most recent decade of years.” Long sentence is adopted here as a “tool” for compressing the greatest posible amount of time, or life, or motion into the smallest unit of time and the smallest possible space, in order to condense and stop it for contemplation. It reveals not only the present, but the whole past on which it depends and which keeps overtaking the present, second by second. Thus the long sentences are not simply functional: they are thematically necessary. Long digression may also result in obscurity. The interrupted chronology in the arrangement of the stories, however, complements the alternation narrative focus of the book and reinforces repetitions that dramatise the past as a force of motion in the presence. Moreover, Faulkner often arranges his fragments around vacancies: events referred to but not described. In this srory, neither Emily’s poisoning of Homer Barron nor her sleeping with his remains for thirty years is actually represented by Faulkner. Doing so, Faulkner deliberately withholds meaning to keep his options open, to keep his story in motion, to intensity the emotional experience. A Rose for Emily is not only a short fiction, but it is of great tension. To read it as merely a piece of cheap Southern Gothicism, an attempt to shock and horrify, would be to miss the point. Also, his other short stories, Dry September, The Old People, That Evening Sun, were included in Fiction 100 An Anthology of Short Stories. The plot summary of other two long novels Light in August Joe Christmas was the illegitimate son of a circus trouper of Negro blood and a white girl named Milly Hines. Joe's old Doc Hines, killed the circus man, let Milly die in childbirth, and put Joe---at Christmas time; hence his last name---into an orphanage, where the children learned to call him "Nigger". Doc Hines then arranged to have Joe adopted by a religious arid heartless farmer called McEachern, whose cruelties to Joe met with amatching stubbornness that made the boy an almost subhuman being. One day in town McEachern took Joe to a disreputable restaurant, where he talked to the waitress, Bobbie Allen. McEachern told the adolescent Joe never to patronize the place alone. But Joe went back. He met Bobbie at night and became her lover. Night after night, while the McEacherns were asleep, he would creep out of the house and hurry to meet her in town. One night McEachern followed Joe to a country dance and ordered him home. Joe reached for a chair, knocked McEachern unconscious, whispered to Bobbie that he would meet her soon, and raced McEachern's mule home.There he gathered up all the money he could lay his hands on and went into town. At the house where Bobbie stayed he encountered the restaurant proprietor and his wife and another man. The two man beat up Joe, took his money, and left for Memphis with the two women. Joe moved on. Sometimes he worked. More often he simply lived off the money women would give him. He slept with many women and nearly always told them he was of Negro blood. At last he went to Jefferson, a small town in Mississippi, where he got work shoveling sawdust in a lumber mill. He found lodging in a long-deserted Negrocabin near the country home of Miss Joanna Burden, a spinster of Yankee origin who had few associates in Jefferson because of her zeal bettering the lot of the Negro. She fed Joe and, when she learned that he was of Negro blood, planned to send him to a Negro school. Joe was her lover for three years. Her reactions ranged from sheer animalism to evangelism, in which she teied to make Joe repent his sins and turn Christian. A young man who called himself Joe Brown came to work at the sawmill, and Joe Christmas invited Brown to share his cabin with him. The two began to sell bootleg whiskey. After a while Joe told Brown that he was part Negro; before long Brown discovered the relationship of Joe and Miss Burden. When thier bootlegging prospered, they bought a car and gave up thier jobs at the lumber mill. One night Joe went to Miss Burden’s room half-determined to kill her. That night she attempted to shoot him with an antiquated pistol that did not fire. Joe cut her throat with his razor and ran out of the house. Later in the evening a fire was discovered in Miss Burden’house. When the townspeople started to go upstairs in the burning house, Brown tried to stop them. They brushed him aside. Ther found Miss Burden’body in the bedroom and carried it outside before the house burned to the ground. Though a letter in the Jefferson bank, the authorities learned of Miss Burden’s New Hampshire relatives, whom they noticed. Almost at once word came back offering a thousand dallors reward for the capture of the murderer. Brown tried to tell the story as he knew it, putting the blame on Joe Christmas, so that he could collect the money. Few believed his story, but he was held in custody until Joe Christmas could be fould. Joe Christmas remained at large for several days, but at last with the help of bloodhounds he was tracked down. Meanwhile old Doc Hines had learned of his grandson’s crime and he came with his wife to Jefferson. He urged the white people to lynch Joe, but for the most part his rantings went unheeded. On the way to face indictment by the grand jury in the courthouse, Joe, hand-cuffed but not manacled to the deputy, managed to escape. He ran to a Negro cabin and found a gun. Some volunteer guards from the American Legion gave chase, and finally found him in the kitchen of the Reverend Gail Hightower, a one-time Presbyterian preacher who now was an outcast because he had driven his wife into dementia by his obsession with the gallant death of his grandfather in the Civil War. Joe had gone to hightower at the suggestion of this grandmother, Mrs Hines, who had a conference with him in his cell just before he escaped. She had been advised of this possible way out by Byron Bunch, Hightower’s only friend in Jefferson. The Legionnaires shot Joe down; then their leader mutilated him with a knife. Brown now claimedhis reward. Adeputy tool him out to the cabin where he had lived with Joe Christmas. On entering the cabin, he saw Mrs Hines holding a new-born baby. In the bed was a girl, Lena Grove, whom he had slept with in a town in Alabama. Lena had start out to find Brown when she knew she was going to have a baby. Traveling most of the way on foot, she had arrived in Jefferson on the day of the murder and the fire. Directed to the sawmill, she had at once seen that Byron Bunch, to whom she had been sent, was not the same man as Lucas Burch, which was Brown’s real name. Byron, a kindly sod, had fallen in love with her. Having identified Brown from Byron’sdescription, she was sure that in spite of his new name Brown was the father of her child.She gave birth to the baby in Brown’s cabin, where Byron had made her as comfortable as he could, with the aid of Mrs Hines. Brown jumped from a back window and ran away. Byron, torn between a desire to marry Lena and the wish to gave her baby its rightful father, tracked Brown to the railroal grade outside town and fought with him. Brown escaped aboard a freight train. Three weeks later Lena and Byron took to the road with the baby, Lena still sreaching Brown. A truck driver gave them a lift. Byron was patient, but one night tyied to compromise her. When she repulsed him, he left the little camp where the truck was parked. But next morning he was waiting at the bend of the road, and he climbed up on the truck as it made its way toward tennessee. Absalom,Absalom! In the summer of 1910, when Quentin Compson was preparing to go to Harvard, old Rosa Coldfield insisted upon telling him the whole imfamous story of Thomas Sutpen, whom she called a demon. According to Miss Rosa, he had brought terror and trategy to all who had dealing with him. In 1833 Thomas Sutpen had come to Jefferson, Mississippi, with a fine horse and two pistols and no known past. He had lived mysteriously for a while among people at the hotel, and after a short time he disappeared. Town gossip was that he had bought one hundred square miles of uncleared land from the Chickasaws and was planning to turn it into a plantation. When he ruturned with a wagon load of wild-looking Negroes, a French artist, and a few tools and wagons, he was as uncommunicative as ever. At once he set about clearing land and building a mansion. For two years he labored and during all that time he hardly ever saw or visited his acquaintances in Jefferson. People wondered about the source of his money. Some claimed that he had stolen it somewhere in his mysterious comings and goings. Then for three years his house remained unfinished, without windowpanes or furnishings, while Thomas Sutpen busied himself with his crops. Occasionally he invited Jefferson men to his plantation to hunt, entertaining them with liquor, cards, and savage combats between his giant slaves-combats in which he himself sometimes joined for the sport. At last he disappeared once more, and when he returned he had furniture and furnishing elaborate and fine enough to make his great house a splendid show-place. Because of his mysterious actions, sentiment in the village turned against him. But this hostility subsided somewhat when Sutpen married Ellen Coldfield, daughter of the highly respected Goodhue Coldfield. Miss Rosa and Quentin’s father shared some of Sutpen’s revelations. Because Quentin was away in college many of the things he knew about Sutpen’s hundred had come to him in letters from home. Other details he had learned during talks with his father. He learned of Ellen Sutpen’s life as mistress of the strange mansion in the wilderness. He learned how she discovered her husband fighting savagely with one of his slave. Young Henry Sutpen fainted, but Judith, the daughter, watched from the haymow with interest and delight. Ellen thereafter refused to reveal her true feelings and ignored the village gossip about Sutpen’ Hundred. The children grew up. Young Henry, so unlike his father, atteneded the university at Oxford, Mississippi, and there he met Charles Bon, a rich planter’s grandson. Unknown to Henry ,Charles was his half-brother, Sutpen’s son by his first marrige. Unknown to all of Jefferson, Sutpen had got his money as the dowry of his earlier marriage to Chareles Bon’s West Indian mother, a wife he discarded when he learned she was partly of Negro blood. Charse Bon became engaged to Judith Sutpen but the engagement was suddenly broken off for a probation period of four years. In the meantime the Civil War began. Charles and Henry served together. Thomas Sutpen bacame a colonel. Goodhue Coldfield took a disdainful stand against the war. He barricaded himself in his attic and his daughter, Rosa, was forced to put his food in a basket let down by a long rope. His store was looted by Confederate solders. One night, alone in his attic, he died. Judith, in the meanwhile, had waited patiently for her lover. She carried his letter, written at the end of the four-year period, to Quentin’s grandmother. About a week later Wash Jones, the handyman on the Sutpen plantation, came to Miss Rosa’s door with the crude announcement that Charles Bon was died, killed at the gate of the plantation by his half-brother and former friend. Henry fled. Judith buried her lover in the Sutpen family plot on the plantation. Rosa,whose mother had died when she was born, went to Setpen’s Hundred to live with her niece. Ellen was already died. It was Rosa’s conviction that she could help Judith. Colonel Thomas Sutpen returned. His slaves had been taked away, and he was burdened with new taxes on his overrun land and ruined buildings. He planned to marry Rosa Coldfield, more than ever desiring an heir now that Judith had vowed spinsterhood and Henry had became a fugitive. His son,Charles Bon, whom he might, in desperation, have permitted to marry his daughter, was died. Rosa, insulted when she understood the true nature of his proposal, returned to her father’s ruined house in the villiage. She was to spend the rest of her miserable life pondering the fearful intensity of Thomas Sutpen, whose nature, in her outraged belief, seemed to partake of the devil himself. Quentin, during his last vacation, had learned more of the Sutpen tragedy. He now revealed much of the story to Shreve McCannon, his roommate, who listened with all of a Northerner’s misunderstanding and indifference. Quentin and his father had visited the Sutpen graveyard, where they saw a little path and a hole leading into Ellen Sutpen’ grave. Generations of opossums lived there. Over her tomb and that of her husband stood a marble monument from Italy. Sutpen himself had died in 1869. In 1867 he had taken young Milly Jones, Wash Jones’ granddaughter. When she bore a child, a girl, Wash Jones had killed Thomas Sutpen. Judith and Charles Bon’s son, his child by an octoroon woman who had brought her child to Sutpen’s Hundred when he was eleven years old, died in 1884 of smallpox. Before he died the boy had married a Negro woman and they had had an idiot son, Charles Bon. Rosa Coldfield had placed headstones on their graves and on Judith’s she had caused to be inscribed a fearful message. In that summer of 1910 Rosa Coldfield confided to Quentin that she felt there was still someone living at Sutpen’s Hundred. Together the two had gone out there at night, and had discovered Clytie, the aged daughter of Thomas Sutpen and a Negro slave. More important, they discovered Henry Sutpen himself hiding in the ruined old house. He had ruturned, he told them, four years before; he had come back to die. The idiot, Charles Bon, watched Rosa and Quentin as they departed. Rosa returned to herhome and Quentin went back to college. Quentin’s father wrote to tell him the tragic ending of Sutpen story. Months later, Rosa sent an ambulance out to the ruined plantation house, for she had finally determined to bring her nephew Henry into the village to live with her, so that he could get decent care. Clytie, seeing the ambulance, was afraid that Henry was to be arrested for the murder of Charles Bon many years before. In desperation she set fire to the old house, burning herself and Henry Sutpen to death. Only the idiot, Charles Bon, the last surviving descendant of Thomas Sutpen, escaped. No one knew where he went, for he was never seen again. Miss Rosa took to her bed and there died soon afterward, in the winter of 1910. Quentin told this story to his roommate because it seemed to him, somehow, to be the story of the whole South, a tale of deep passions, tragety, ruin, and decay. A Reason for Nobel-“for his power and artistically unique contribution to the modern American novel” Banquet Speech I feel that this award was not made to me as a man, but to my work -- life's work in the agony and sweat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before. So this award is only mine in trust. It will not be difficult to find a dedication for the money part of it commensurate with the purpose and significance of its origin. But I would like to do the same with the acclaim too, by using this moment as a pinnacle from which I might be listened to by the young men and women already dedicated to the same anguish and travail, among whom is already that one who will some day stand where I am standing. Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat. He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid; and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed -- love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, of victories without hope and, worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands. Until he learns these things, he will write as though he stood among and watched the end of man. I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal simply because he will endure: that when the last ding-dong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking. I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer's, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet's voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail. 曹静 1001 班