The Economics of Homeland Security

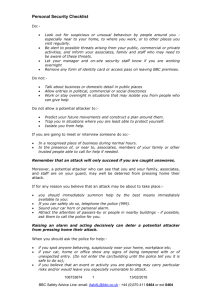

advertisement