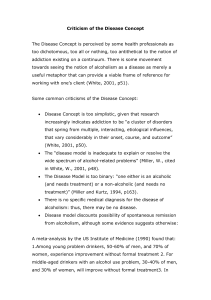

alcoholism - Innovative Educational Services

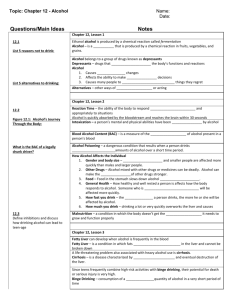

advertisement