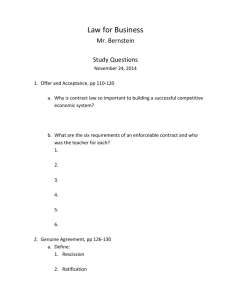

CONSIDERATION

advertisement