Sylvia Plath: dynamic concepts, a storm

advertisement

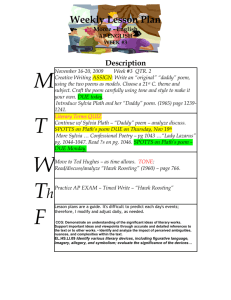

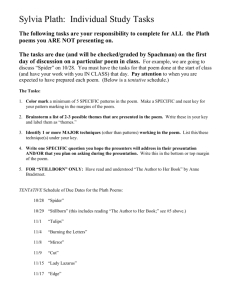

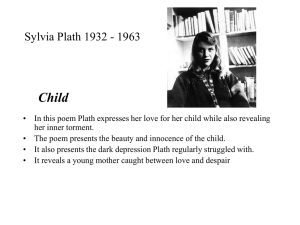

Sylvia Plath: dynamic concepts, a storm-tossed life. (BOOK WORLD) Publication: World and I Publication Date: 01-OCT-06 Author: Stern, Fred COPYRIGHT 2006 News World Communications, Inc. Perhaps there is no poet who has created as much excitement in both literary and feminist circles as the New England writer Sylvia Plath (1933-1963). Plath reached the height of her career shortly before her death in the early 1960s, but her poems are as fresh today as they were then. In those poems, she created an internal landscape of such meaning and scope that she remains the object of fan clubs, the topic of bloggers across two continents; and her life is the subject of biographies produced at a rate of four or five per year. Sylvia Plath spent her brief life on both sides of the Atlantic: the United States and Great Britain. But geography played only a minor part in her dramatic presentations. However, her poems sometimes appear in British anthologies of poetry, and, of course, they are in almost every anthology of American poetry where they are likely to remain for generations into the future. The elements of Plath's life can be easily established through her journals, her letters, and in more artistic and penetrating form, the 274 poems that frame the years of her all too brief life. Sylvia Plath was born in Boston on October 27 (prophetically, sharing that birthday with the noted Welsh poet, Dylan Thomas, who like Plath would also have a strong influence on the direction of twentiethcentury English language poetry). Her father, Otto Plath, was a college professor of entomology, the study of insects. His specialty was the life of the bumblebee, and his daughter would later write a number of poems that have bees as their primary theme. She lost her father at age eight, and as she confessed to a friend, she alternately adored him and hated him for "abandoning her." Her mother, Aurelia, was also a teacher, but unlike her father, was cool and domineering, causing a wall of resistance to spring up between daughter and mother. Her father's premature death haunted Plath and perhaps set her on the pathway to depression and tragedy. It was not until many years after his death that Plath actually visited her father's grave for the first time. In her poem, titled after the ancient Greek tragic story of a daughter Electra in love with her father, Plath writes with stunning incisiveness and painful self-accusations: Electra on Azalea Path The day you died I went into the dirt, Into the lightless hibernaculum, Where bees striped black and gold, sleep out the blizzard Like hieratic stones, and the ground is hard It was good for twenty years that winteringO pardon the one who knocks for pardon at Your gate father-your hound-bitch, daughter, friend. It was my love that did us both to death. Early success of a precocious poet Plath had her first poem published at the amazing age of eight. Other publications followed, notably in the magazine Seventeen, reinforcing her early love for writing and no doubt whetting her appetite for the satisfaction that goes with seeing one's work in print. A highlight of her teen years was a scholarship to Smith College, awarded upon her high school graduation. In 1953 she became a "guest editor" (the equivalent of what we now call an "intern") at Mademoiselle magazine in New York City. Plath could not endure the stress and overwork in the high-tension publishing world, and suffered a nervous breakdown. It would not be her last such episode. The Bell Jar a depiction of the episode and its resolution was published under a pseudonym in 1963, then with her own name posthumously in 1971. Back at school and writing again, her ambition returned. She applied for and was awarded a prestigious Fulbright Scholarship. Soon she was aboard the Queen Mary for a thrilling voyage to England, to study at Cambridge University. A transatlantic life At Cambridge she met Ted Hughes, a British poet who celebrated the fauna and flora of England in his poems, and who in later years was to become England's poet laureate. Plath and Hughes married secretly in 1956 on "Bloomsday." (Bloomsday, June 16, is the day on which all events in James Joyce's novel Ulysses take place). During that newlywed summer she seemed truly happy, which is reflected in a number of her poems from that time. In this excerpt from "Wreath for a Bridal," she writes of weddings and marriage--"let flesh be knit"--in a unique, yet very romantic way: Wreath for a Bridal From this holy day on, all pollen blown Shall strew broadcast so rare a seed on wind That every breath, thus teeming, set the land Sprouting of fruit, flowers, children most fair in legion Today spawn of dragon's teeth: speaking this promise, Let flesh be knit, and each step hence go famous. The poem has a distinctly Elizabethan tone, a voice that she had seldom before used and which she soon abandoned, returning to her far more original mode of versifying. Anxious to further her career, Plath accepted a teaching position in the English department of Smith College, her alma mater. While there, however, she went through a prolonged period of "writer's block," unable to express her thoughts as she wished, and at a more primitive level, unable to compete with the current luminaries of the poetic world, such as Marianne Moore and Elizabeth Bishop. She was deeply troubled by her inability to fulfill the high standards she set for herself. Although her new husband was with her, the pressures of academic life proved too great for Plath, and she resigned after a year. Her inability to tolerate stress was becoming a disturbing pattern, one predictive of disaster down the road. Hughes and Plath returned once again to England, where prospects for the young couple would move to the upswing. Ted Hughes had his first book accepted for publication. And, happily, Plath's writer's block was finally broken. She landed a "right of first refusal" contract with the New Yorker magazine. This type of contract meant that the magazine would have "first dibbs" on every poem she wanted published; other publications could use it only if the New Yorker declined to publish it. To this very day, publication in the prestigious and influential New Yorker is a lofty goal for a poet, and a "right of first refusal" contract is highly desirable, because the magazine's reputation and scope catapults a poet from obscurity to national recognition. The magazine published many Plath poems, and her reputation did indeed become established. Among her poems appearing that year, 1958, was "In Midas Country." It's a typical Plath poem: straightforward, with nothing tentative about it. In Midas Country It might be heaven, this static Plenitude: apples gold on the bough, Goldfinch, goldfish, golden tiger cat stockStill in one gigantic tapestryAnd lovers affable, dovelike. So we are hauled, though we would stop On this amber bank where grasses bleach. Already farmer's after his crop. August gives over its Midas touch, Wind bares a flintier landscape. With "In Midas Country," Plath gained an even stronger foothold in the world of poetry. Projecting a serious, yet sensual note, this work became and remained Plath's signature poem for quite awhile. In October 1959, Plath returned once more to Boston. She enrolled in a poetry class with Robert Lowell, who had fashioned the concept of the "confessional poet." Lowell would celebrate this by no means new philosophy, with his next book Life Studies. "Confessional poetry" frees the poet so that when writing about himself, he can relate every experience, any thought or emotion without trepidation, and be assured of a sympathetic readership. Plath learned much from Lowell, although in the strictest sense she cannot be considered a confessional poet. Her work was only partly autobiographic with its details owing as much to her imagination as it did to actual occurrences. In Boston she met another young writer, Anne Sexton, who like Plath would become a major figure in American poetry. Plath had a profound influence on Sexton's writings, and the two women remained lifelong friends. Again, Plath and Hughes returned to England. It would be her last transatlantic voyage. It's unclear whether the ongoing instability in Plath's life--the disruptions of moving back and forth across the Atlantic and changing domiciles- -was a source of excitement and stimulation, or a cause of insecurity and unhappiness. Certainly London, where they initially settled after this latest journey, offered much in the way of stimulation for a writer. London was the vortex of literary life, attracting successful writers as well as would-be authors from all over the English-speaking world. Hughes signed a book contract and so did Plath, a collection entitled The Colossus and Other Poems. And she was expecting her first child. Coping with misfortune Soon, Frieda was born and the Hughes family, seeking a more suitable environment for their young daughter, moved once again, this time to a little market town in Devonshire, not too far from London. Their new house was called "Green Court." Here Hughes grew vegetables while Plath tried her hand at beekeeping. In this idyllic setting and pregnant again, she wrote her mother, "This is the happiest time of my life," even though the reviews of Colossus had been tepid. Then, misfortune struck. She suffered a miscarriage in 1961. We read about it in "Stillborn." Here are excerpts from the poem. Stillborn These poems do not live: it's a sad diagnosis. They grow their toes and fingers well enough And still the lungs won't fill and the heart won't start. Shortly thereafter they had another child, Nicholas, whose arrival she celebrates in this poem. Nick and the Candlestick Love, love, I have hung your cave with roses, With soft rugs You are the one Solid the spaces lean on, envious, You are the baby in the barn. During this period, Plath overheard a fateful telephone conversation between her husband and the wife of a poet the Hughes' had befriended. She learned that Hughes was having an affair with the woman. Devastated by the infidelity, Plath separated from her husband and returned to London with Nicholas and Frieda. One of the effects of her husband's deception was to spur Plath to even greater productivity. We could speculate she was inspired in part by the location of her newly rented flat; it was in the same building where the Irish poet W. B. Yeats had once lived. In any event, in the short span of a little over a month she wrote an astonishing number of high quality poems. These were placed in a black loose-leaf notebook, which would later be published under the title Ariel. It was an unusually cold and dreary winter. Finances were tight. And Plath, with a history of emotional fragility, was perhaps suffering more than most from the depression that sometimes accompanies childbirth, now (but not then) a recognized phenomenon. On February 11, 1963, carefully shielding her two children safely asleep in their bedroom, Plath turned on her gas stove. This time, her suicide attempt was successful. Integrity and honesty In all of the poems in which she writes of herself, Plath is clinically, sometimes brutally honest. Her lack of self-deception is documented in poem after poem. And all of her poems have an immediacy not equalled in contemporary writing. She read her poetry frequently on English radio's BBC. Her voice had a solemn but modest quality. Even after a single hearing of these poems, or after reading them only once, they were likely to be unforgettably etched in one's memory. Although Plath's early poems appearing in the New Yorker and in Colossus brought her considerable acclaim and firmly established her reputation, it is her last book, Ariel, published posthumously, that is truly and consistently unique, and likely to guarantee her a lasting coveted position in the world of poetry. Had Plath not composed the poems in this final sequence, perhaps her name would have been consigned to the purgatory of merely "good contemporary poets" read only by enthusiasts, or excavated by students writing master theses or doctoral dissertations. Like other great poets, Plath's work evolved steadily in her early creative years. Her self-knowledge increased geometrically, and her hold on language became solid bedrock. She had discussed the new direction her writing was taking with her estranged husband, and after her death Hughes took charge of the black loose-leaf notebook containing her last group of poems. Acting as a self-appointed editor, he added as well as deleted poems and rearranged the poems in the sequence he thought best suited for publication. The result was Ariel, her signature book. Although separated from his wife, they were still legally married at the time of her death, and Hughes felt an obligation to have her work presented in the best possible way. Yet, there is a great deal of controversy about his actions. Was he correct in taking liberties with Plath's poetry? Did he violate her intent? Of course, being an editor put him in a position to remove poems that were critical of him, which he did. Years later, Frieda Hughes, the daughter of the two poets and herself a fine poet, reinserted the deleted poems, reordered the poems to their original sequence, and published the restored edition in 2004. Both versions of Ariel are bestsellers. Much has been made of the opening and closing words of the original poem sequence, which begin and end the poems with an upbeat, positive tone. These words are "love" and "spring," respectively. In between these words and the poems that contain them, Plath covers every conceivable emotion--hate, anger, frustration, pity, horror, rebellion, blind acceptance of fate and more. Throughout Ariel, Plath uses metaphor, the two main ones being fauna and illness. For example, in "The Rabbit Catcher" she reveals her feelings on the restrictions within her marriage, as demonstrated in these excerpts: The Rabbit Catcher And we, too, had a relationshipTight wires between us, Pegs too deep to uproot, and a mind like a ring Sliding shut on some quick thing. The constriction killing me also. There are some poems which so powerfully describe an object that one cannot think of or see the object thereafter without recalling the poem in its entirety. The poem "Tulips" is a good example. In "Tulips," the writer is in a hospital where "they have swabbed me clear of my loving associations" and "they bring me numbness in their bright needles, they bring me sleep." The tulips escort the lines throughout the poem, which ends with the tulips' diffusion throughout the room: Tulips Nobody watched me before, now I am watched. The tulips turn to me, and the window behind me Where once a day the light slowly widens and slowly thins, And I see myself, flat, ridiculous, a cut-paper shadow And Plath actually expresses a fear of the flowers: The vivid tulips eat my oxygen. The tulips should be behind bars like dangerous animals. "Ariel," the title poem of its sequence, was the name of the horse Plath rode. But the poem "Ariel" is not simply about the horse. As in almost everything that she wrote, she uses the poem's overt subject as a vehicle to express other thoughts and feelings, in this case, her inner turmoil. The poem's language is brisk, sharp and brittle. Ariel Something else Hauls me through airThighs, hair, Flakes from my heels. White Godiva, I unpeelDead hands, dead stringencies. Eye, the cauldron of morning. Like many women in the 1950s she became aware of the unfair discrimination between the sexes, made evident in a poem like the following: Lesbos Viciousness in the kitchen! The potatoes hiss. And my child-look at her face down on the floor, I should wear tiger pants, I should have an affair We should meet in another life, we should meet in air. As before, she writes about bees, and bees are also often called upon to serve as a metaphor. These poems draw upon her personal experience with her own beehives in Devonshire, and of course, hark back to her father, the entomologist. In "The Bee Meeting" we learn of her insecurity, her discomfort at meeting other people. She writes, "In my sleeveless summery dress I have no protection" and "I am nude as a chicken neck, does nobody love me?" She continues, The villagers open the chambers, they are hunting the queen. Is she hiding, is she eating honey? She is very clever. She is old, old, old, she must live another year, and she knows it. While in their fingerjoint cells the new virgins Dream of a duel they will win inevitably, I am the magician's girl who does not flinch. In "The Arrival of the Bee Box" the poet receives a new hive. "It is the noise that appalls me most of all," she writes imploringly. "I have simply ordered a box of maniacs" ... "I am no source of honey" ... "why should they turn on me? Tomorrow I will be sweet God. I will set them free. The box is only temporary." When she writes "set them free" she seems to be expressing her outlook on life, and she strikes a note which lingers in our thoughts and which we can understand in our attempts to confront our own fears. Fred Stern has explored the creative efforts of artists and writers worldwide. His work has appeared in European and Asian publications as well as on Artnet.com. He writes a bimonthly column on the arts for Commuter Week and is a frequent contributor to The World and I Online. He has given courses on American writers and has taught poetry and creative writing at the Institute of New Dimensions. He has lectured widely on these topics. A volume of his verses is scheduled for appearance in 2006 under the title Corridors of Light.