Verbal Magic and Other Forms of Magic 1. Let us continue our

advertisement

Verbal Magic and Other Forms of Magic

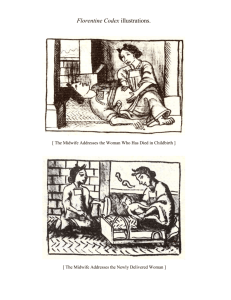

1. Let us continue our discussion of rodiny. One of the midwife's tasks, according to a popular belief, was

rendering assistance in delivery and bathing of the birthing mother and the baby during the first, most

dangerous, days thereafter (some three days, in other places, seven or even nine). That is why many

sources often cite that "the midwife must leave only after that by saying: 'In the name of the Father and

the Son and the Holy Spirit. Like these stones are sleeping and keeping silent; they never cry, never

shriek and don't know anything: neither lessons, nor tendance, nor hexes, nor slander, nor sorrow - so

should thou, baby, servant of God, sleep and keep silent, never crying and knowing anything: neither

lessons, nor tendance, nor hexes, nor slander, nor sorrow. Let my words be firm and tight, very firm and

doubly tight; there is a key to my words, and a lock, and a seal of steel'. Having said this spell over the

water, she started washing the baby with that water..." (cited from: P.S. Efimenko, the Arkhangelsk

Governorate). It was believed that being bathed in such water will bring the baby both protection and

comfort in the beginning.

The midwife cut the umbilical cord or, depending on the baby's sex, even axed it (if a boy) or chopped it

using a spinning wheel or a spindle (if a girl). That was done for the children to be a good hand at their

craft. The cord was often tied with flax or even hemp, plied into a thread. The cut was anointed with

fresh butter or vegetable oil. When it was, as it is called now, a precipitate labour (i.e. unexpected) and

the woman had to go through it alone, she cut the cord with her teeth and tied it with her hair pulled

out of her braids. Sometimes she added a linen thread taken out of the hem of her shirt.

The cut-off cord piece was sometimes knotted, dried and could be stored in a safe place (in a chest or

behind the icon case). It was believed that if the mother gave that knot to her undergrown daughter to

untie it, she would become a skilful spinstress. And if such a knot was given to a childless woman (either

a relative or a complete stranger), she would surely be cured of her infertility.

Yet, more often and according to the custom, both the cord and the afterbirth (placenta) were buried, in

most cases in the corner of the house (somewhere under the sill) or in any other clean and safe place

and sometimes under the threshold of the house. Before that, the placenta was always washed up and

wrapped into a clean cloth and then put onto a piece of birchbark or into an old straw shoe. A slice of

bread, a handful of corn and an egg were also put there - for the baby to grow into a happy and a

wealthy person. We can see that the rites of afterbirth burial demonstrate an important function of the

childbirth rites, namely an exchange of valuables with the "other" world, where the baby has been

received from. According to archaic beliefs, earth is a natural sphere, therefore it is not cultivated;

moreover, it is a life-giving womb. So placenta burial is an equivalent gift to the earth, in exchange for

what has been received. The afterbirth-connected rites prove that there was a belief in Rus' as well as in

many other nations that the placenta was a newborn's counterpart. Such moments as the following

ones pointed at that indirectly:

— the rituals performed by the midwife over the afterbirth were duplicating the rituals performed by

her over the baby;

— an essential requirement to keep the afterbirth safe and sound because the newborn's health

depended on that directly;

— finally, it was the earth that the afterbirth was most often buried in, and in any case the only term

was used to signify this ritual, namely "to bury" the afterbirth.

Moreover, there was quite a clear dependence of the birthing mother's health on the correct treatment

of the afterbirth: it was believed that unless it was buried she will be sick and there may even be a

threat to her life. That was often why people used to say, while burying the afterbirth: "Go back to the

earth what was taken from the earth and the servant of God (name of the woman) will stay on earth".

The bond between the afterbirth and the newborn was somewhat projected on the baby's future - on

the whole infancy of his or her life. If the afterbirth was buried somewhere in the garden, oatmeal or

barley could soon be sowed there. When the stems grew five centimetres long, they were cut, dried,

ground and used as a universal remedy in the treatment of most of the childhood diseases (let us note

that this "panacea" was effective, first of all, for a child whose placenta had nourished that "medicine).

Judging by the afterbirth, people could "see" the future children as well. By its shape they could tell the

sex, for example: a round shape symbolised the female while the elongated one - the male. It was not

only the shape that was studied bit also the nodes on the placenta. The number of such nodes could tell

how many more children this woman was going to have (the same knowledge was used when it came to

animals, e.g. a fresh calved cow). A "clear" afterbirth meant there will be no more children. A buried

placenta could help influence the future children. For example, in the Vladimir Governorate, if people

wanted only boys to be born in future, they buried the placenta wrapped in the back of a men's shirt.

Summing up, both the afterbirth burial and keeping it safe and all the rituals that could be performed

over it guaranteed not only the future well ness of the baby and mother but also the birth of new

children. That means we can speak of the afterbirth as of a means of communication between the living

and the ancestors' world. The earth in these rituals plays the role of a life-giving source for future

generations. Old straw shoes, if we mean the archaic functions of old shoes, were needed for a passage

to the afterworld (i.e. the afterbirth went in such a "package" <equal to a transportation means> to the

world of the dead). Moreover, old straw shoes were associated with fertility. Thus, an old shoe, together

with the afterbirth buried with it, can be considered a sacrifice to the earth in exchange for the valuable

received from it, i.e. the newborn baby.

2. If a baby was born "in a caul" (sometimes referred to as "in a veil"), i.e. in the amniotic sac, the intact

bag of waters, it was considered a sign of good fortune. The amniotic sac was washed up, dried, sewn up

into a piece of cloth and either stored on the icon case or worn around the neck as a strong amulet,

together with the baptismal cross, never taking it off. A.V. Balov has noted the following in his

Poshekhonye Sketches : "The caul, which a baby is sometimes born in, ranks among the amulets. If this

caul is worn around the neck, you will be lucky and happy throughout your whole life". It was believed

that "the caul" can save its owner from various mischiefs and disasters, help in finding truth in court,

save from drowning in the sea, helps women be cured of infertility and helps them stay alive in a

difficult delivery. There are many stories about the fact that, in case of fire, people were rushing first of

all to save not their valuables and savings, not even the icons, but "the caul".

Speaking of the clothes, let us mention a very popular old custom. We mean the custom of wrapping a

newborn into some of its parents' clothes. It is known to almost all of the European nations. The most

interesting and significant fact about that is the motivation of the custom itself, connected with the

interpretation of the function of the traditional “male/female” opposition. The English, for example,

believed that a boy has to be wrapped into his mother's clothes while a girl - into her father's. The

generally accepted motivation of this act is a belief that in future it will surely bring luck to a person of

the opposite sex. Thus, the Radfords' Encyclopedia of Superstitions mentions an old variant of this

custom, typical of the County of Kent. Local midwives prepared two shirts before the delivery: one for a

boy and one for a girl. If a girl was born, she was put onto a boy's shirt; if it was a boy, he was put onto a

girl's one. That had to exert a positive influence on the newborns' fate: a boy will charm all the women

when he grows up and a girl will be courted by many men so the will be able to choose a good husband.

The same book contains a very interesting, to our mind, commentary of a midwife: "If I don't do this, I

shall not be permitted to look in the face of this baby until he or she grows up. Then why must they

suffer if I can bring them luck?"

Of course, the given motif cannot be taken for the original one, and this custom has obviously

undergone some transformation, because it is based on an adapting action meant to introduce a soul

coming from the "other" world as a kin. In the Russian North there was just the same explanation: "...

when born, it is wrapped into a men's shirt, which must be unwashed and worn, so that the father could

love the baby more". Let us also note that in the Russian tradition, unlike the mentioned English one,

there was a more ancient way of dividing into male/female: a boy (as belonging to the male part of the

family) was wrapped into his father's old shirt, while a girl was wrapped into the hem of her mother's

shirt. The weariness and sweatiness of the shirt increased its marking as an attribute of kin (both in the

family sense and in the sense of life - for the dead, as we know, never sweat). That was why that

custom, apart from its adapting meaning, also had a strong apotropaic (defensive) meaning. It was also

believed that such swaddling promoted a good and correct development of the baby - it will be growing

up better. Let us add that instead of a father's shirt father's pants were used sometimes: the baby was

wrapped into them in order to become calm and reasonable.

3. Not only did the midwife delivered the baby, checked if it was alive and washed it up but she also

could, if considered it necessary, correct the shape of its head (she was patting the newborn's head with

her hands, shaping it). In a word, it was believed that it was the midwife that was responsible for making

a person either chubby or long-visaged or even ugly. The same she did to the newborn's nose, by patting

and squeezing its nostrils, for them not to be too broad and flat. She also stretched the baby's little arms

and legs, for them to be straight and equal... "God bless you! Grow up, you little arms, and become

more plump and robust; walk around, you little legs, carrying your body with you; speak and talk, you

little tongue, and feed your own head. The old Solomoneyushka has been washing and adjusting you,

asking for God's protection: Don't you ever sit, just walk on your legs..." (a spell used during the washing

of a newborn).

For obvious reasons, people believed that all the complaints concerning both the physical defects and

unattractiveness can be filed at the midwife: "the old woman has adjusted like that" (only when the

parents themselves have violated no bans being in force at the time of the conception and during the

pregnancy).

4. Upon coping with the baby, swaddling it and laying it into the crib, the midwife started attending to

the mother: washed her in the bathhouse, adjusted her belly, cared for the milk to appear and increase.

One of the midwife's main concerns was the recovery of the mother's wholeness. Her empty body had

now to be brought into its normal state: the old woman had to put all the troubled organs "where they

belong", to re-assemble the woman's body, if we can say so. The womb was the organ of the highest

concern, for it was the womb that played the most significant role in the process of the baby's formation

and development. In the spells it was called zolotnik, 'the golden one', and was treated most

respectfully. It was much flattered when saying spells: "Oh, Zolotnichek, Yakimnichok, a little man of

God, I beg you, I pray that you never fall out, never come to the sides, never fall on the back, never cool

a meal, never spoil the beauty and never interfere with anything. Please stay where you should be,

where your mother has placed you, in your golden chair. Under the navel, under the ball of gold. Oh,

Lord, please render them assistance for ever, for good. Let them be healthy and well again" (recorded

by G.I. Kabakova, Polesia).

The midwife made a special drink for the birthing mother's quick recovery. That drink was intended to

make the woman's body improve in health and strength, to recover "the colours" and produce enough

milk. The drink was based on red wine, with a set of various healing herbs and spices added.

Moreover, the midwife's second, no less important, responsibility was to protect the birthing mother

from evil spirits. She stayed with the woman and her baby practically in private for three or four days

(and in some locations the period of particular "impurity" was prolonged up to seven or even nine days),

in an uninhabited building that, as it has been already mentioned, was considered a dangerous, ritually

impure place (in particular when speaking of a bathhouse - it was merely called "a foul dwelling") - and

an "open" one since it is, in a way, a "crossroad" of the two worlds. To protect the birthing mother in

such a place from spirits of illnesses, from evil spirits' attempts to spoil her body or take away her soul, a

knife, certain enchanted herbs and three interwoven wax candles were put under the headbed. An oven

fork was put by the stove with its horns upwards for just the same reason. If the woman had to go out,

she used it as a stick to lean on. Meanwhile, the midwife, as D.K. Zelenin characterised her role, "not

only helps the woman to give birth but also rousts her out of bed if needed and heals her and bathes

both her and the baby. She can even cook a dinner instead of her and milk the cow, etc. In cases when

there was only one grown-up woman in the family, the midwife plays at the same time the role of a

hostess, i.e. does all the necessary housework until the woman is able to work herself".

To do the housework, to cook the dinner and to milk the cow - all that, in fact, became possible only

with the loss of clear vision concerning the fact that the midwife was only a mediator during the delivery

period and undertook a world-connecting mission. A mediator's status and functional characteristics

imply that she is wholly and inevitably marked by the abovementioned ritual impurity. In the old days it

was clearly illustrated by the fact that, until she had undergone a purification ritual, the midwife could

not go and help another birthing mother even if she was in the immediate vicinity of her place. It was

not the distance or lack of the willingness to help that restrained the old woman but her own ritual

impurity.

5. Only after the delivery was over, the birthing mother's relatives and neighbours were informed

thereof, by hanging the mother's shirt near the door of the house or near the bathhouse on the pole. It

was a sign for the female neighbours, particularly for those having children, that "there was another one

for their ranks" and they could visit the mother. That rite was called navedy ('calling on') and it was wellknown to many peoples of Central and Eastern Europe. Let us note once again that it was only married

women with children who could 'call on'. They were required to bring some tasty treat. Yet, almost

every "treat" was easily defined as a ritual dish: porridge, pancakes, pies. All that was meant for the

mother, to taste "barely a mouthful" and stimulate her appetite. Her children, if she had any, could eat a

bit of the treat but her husband was strictly prohibited even to touch that food.

6. In this regard I would like to touch upon another food taboo. Even if it has the same roots with the

abovementioned one, they are very deep. Even today both midwives and parous women often say the

following about the delivery: "Like you forget an arduous hill, you forget the delivery process". The motif

of quick oblivion of labour (passing by the road between the worlds), dates back, according to T.Yu.

Vlaskina, to very ancient concepts about the need to hide information on passing through the sacral

space and time of "the passage". Strong beliefs concerning "piling the souls of the dead with food and

drink" prove that. It were special food and special drinks and they were believed to bring "oblivion" (see,

for instance, the inevitable custom of drinking water from the river of oblivion practiced by ancient

Greeks). So, the Russian tradition has kept only a verbal motif of the oblivion of the way passed. Yet,

Southern Slavs do have its ritual decoration, too: soon after the baby is born special bread for the Holy

Mother, who is the birthing mother's recognised patroness, has to be baked. "Upon having seen that the

bread has been baked, the Holy Mother leaves the birthing mother, by tipping her on the cheek with her

hand and saying 'Please forget it!' for the woman to forget her labour pains. Then the Holy Mother

departs to help other women. The birthing mother had no right to eat this bread."

7. The rites symbolising the acceptance of the baby into the family and the community started with the

christening party. Unlike other Christian churches that practise confirmation that has replaced the

archaic initiation forms, the Orthodox church practises only baptism. That is why Russian church

christening combines purification rites, acceptance of the newborn into the family and the name-giving

ritual.

The common tradition of the Eastern Slavs has not kept any churchless rite of name-giving. Yet, there

had been, until recently, an interesting custom of giving a second name to a baby, apart from its official

one, e.g. Zhdan (from dolgozhdanny, 'long-awaited'), Pervusha (from pervy, 'the first'), Tretyak (from

trety, 'the third'), etc. In such cases people try not to use the official name. The double name custom

had been very popular until the 17th century: the first name was given in accordance with the church

calendar, the second name was a pagan one. The famous 11th century Ostromir Gospels can serve as an

example thereof. It has got its name from its ordering party whose church name was Iosif and the

secular one was Ostromir. The church name was chosen within eight days before and after birth. It was

preferred that the corresponding saint be older (i.e. in accordance with the calendar his or her day

should be earlier than the baby's birthday). The guardian angel was thought to be stronger in such cases.

The name was enormously important it signified the person's inclusion into the human society and

influenced the fate of its bearer. Once the main role in the name choosing belonged to the midwife;

later on it was transferred to the godfather and the godmother (kum and kuma).