Subject to Authority: Hamlet, The Prince, Resistance to Civil

advertisement

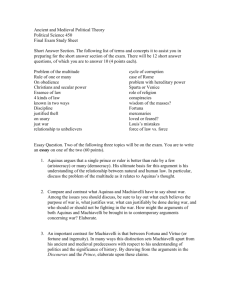

Subject to Authority: Hamlet, The Prince, Resistance to Civil Government Unit Introduction Greetings Friends, Today we begin a unit on “authority,” in which we will study three texts. The main focus of the unit will be William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, an exhaustive, probing study of the modern humankind in the form of a revenge tragedy set in the prison known as Denmark. Many of the questions which Hamlet presents to us will serve as a guide for our study of two political essays/treatises: Machiavelli’s The Prince and Henry David Thoreau’s Resistance to Civil Government, or Civil Disobedience. The purpose of reading these three texts together is to encourage creative answers to complex questions. What is the relationship between human nature and authority? What is the relationship between divine authority and human authority? What is the role of the individual in relation to these two types of authority? These are just some of the questions we will trace through our examination of these three texts. Required Texts: Hamlet, The Prince, and Civil Disobedience Unit outline (subject to change) 1. The Prince 2. Civil Disobedience 3. Hamlet, Acts 1-2 4. Hamlet, Acts 3-4 5. Hamlet, Act 5 6. Essay Workshop Grade requirements for this unit will be as follows: reading quizzes, 1 public speaking engagement, 1 group presentation, 1 discussion paper, 1 passage analysis, and participation (totaling 200 pts), choice of 4 short essays (1 page max each, choice, 200 pts) Essay Topics (complete 4 total) The Prince Essays (choose 1): 1. Discuss Machiavelli on the relationship between the political leader and the citizen. What is the nature of each? What is the responsibility of each in relation to the other? Support with quotes from the texts, interpret them in support of your argument, and cite them properly. You also may wish to demonstrate the similarities and differences by proposing a hypothetical political scenario or issue and discuss how each side would act. 2. Discuss Machiavelli’s views regarding free will. To what extent can historical events be shaped by individuals, and to what extent are such events the consequence of fortune and circumstance? Give examples to illustrate your reading. Civil Disobedience Essays (choose 1): 1. Thoreau believes that people should not participate in injustice but that they do not have to actively promote a more just world. What is the difference between these two concepts, and why does Thoreau make this moral distinction? Evaluate his position, providing examples. 2. Thoreau asks rhetorically, "Must the citizen ever for a moment, or in the least degree, resign his conscience to the legislator?" How would you answer this question? Is compromise on moral issues a necessary part of living with other people? Hamlet Essays (choose 1): 1. Argue for Hamlet's sanity or insanity, supporting with key pieces of evidence and interpreting them in order to prove your case. You must also acknowledge how the opposing view would interpret that piece of evidence, and then explain why your interpretation is superior. You must use quotes from the play as your pieces of evidence, and site them properly in your essay. 2. Does Hamlet “delay” his revenge? If so, why? If not, why? Support with quotes from the text, interpret them in support of your argument, and cite them properly. 3. How does Hamlet change over the course of the play? Support with quotes from the text, interpret them in support of your argument, and cite them properly. Is Hamlet an admirable hero, why or why not? 4. Compare and contrast two characters in the play. For example: Hamlet and Laertes, Ophelia and Gertrude, Polonius and “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern”, or any two main characters you wish. Tell how they are similar, how they are different, and why these similarities and differences are important to the play. Support with quotes from the text, interpret them in support of your argument, and cite them properly. Texts in Conversation Essays (choose 1): 1. Discuss Machiavelli’s qualities for a successful Prince. How do both Hamlet and Claudius meet or fall short of these qualities? Which one would make the better Prince? Be sure to consider the theme of “appearances and reality” in both texts, citing specific examples. 2. Discuss Machiavelli on the relationship between Fortune/Providence and human action/free will. Compare and contrast this with Hamlet’s attitude concerning the complexity of action and Divine Providence in the play. Cite at least three concrete examples from the play to support your argument. 3. Compare and contrast Hamlet and Thoreau on the issue of conscience. What role does conscience play in forming human action? 4. You may create your own essay question. The only requirements are that 1) you do not simply re-hash a previous; and 2) you discuss at least 2 of our three texts on your chosen topic. Hamlet Passage Recitation Options and Dates Dainty You are to choose one passage to memorize and recite before the class. You may choose to work with a partner(s) and recite a passage that specifies two or more people. If choosing the partner option, the lines must be divided evenly among the partners, and each must deliver no fewer than 10 lines (see me concerning prose passages). Assignment is worth 30 quiz points and you will be graded not only on how precisely you render the text, but also on interpretation and delivery (in other words, you have to perform the passage). You must sign up for a passage and date by TBA. 1st recitation: TBD Page 9: “Seems Madam…” Page 10-11: “O that this too too sullied flesh…” (3 people) Page 17: “Yet here Laertes…” (2 people) Page 23: “I am thy father’s spirit…” Page 25: “ O, all you host of heaven…” (2 people) Page 28: “And therefore…” Page 32: “He took me by the wrist…” Page 41: “I will tell you why…” (2 people) Page 49: “O what a rogue and peasant slave…” (4 people) 2nd recitation: TBD Page 53: “To be or not to be…” (3 people) Page 55: “O what a noble mind…” Page 62: “So many journeys…” Page 68: “’Tis now the very witching hour…” Page 69-70: “My offense is rank…” (3 people) Page 70-71: “Now might I do it pat…” (2 people) Page 77: “Not this, by no means…” 3rd recitation: TBD Page 83: “And England…” Page 85: “How all occasions…” (3 people) Page 95: “O, for two special reasons…” Page 98: “Not that I think…” Page 99: “Let’s think further…” Page 106: “Alas, poor Yorick…” Page 109 and page 116: “Sir, in my heart…” and “Not a whit…” Hamlet Study Guide 1.1 1. At the very beginning of the play, Bernardo comes to relieve Francisco from his guard shift. What is the significance of this scene? In other words, why begin with this scene? What does it reveal about Denmark? 2. What do Horatio and Marcellus plan to do at the end of Scene 1? 1.2 1. What 4 topics does Claudius discuss in his first speech at the beginning of Scene 2? 2. What does Laertes ask Claudius? 3. Describe the argument between Hamlet and Gertrude: What does she tell Hamlet to do? What does she then ask him? How does he respond? Why does he respond this way? 4. What does Hamlet mean when he tells Horatio that he thinks he sees his father “in [his] mind’s eye”? 5. What does Hamlet plan to do after Horatio tells him about the sighting of his father’s ghost? 1.3 1. What advice does Laertes give to Ophelia before leaving for France? 2. How does Ophelia respond to Laertes’ advice? How does she challenge him in return? 3. What advice does Polonius then give to Ophelia? What does he tell her to do? 1.4 1. What is Horatio afraid the ghost might do to Hamlet? 1.5 1. What does the ghost tell Hamlet? 2. What “one poor request” does Hamlet make Horatio and Marcellus swear by his sword? 3. What does Hamlet ask of Horatio in 1.5:174-189? 2.1 1. Who is Polonius sending Reynaldo to visit? 2. What frightening experience does Ophelia describe to Polonius? 3. How does Polonius react to this information? 2.2 1. At the very beginning of 2.2, what does the King ask of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern? 2. In 2.2:60-80, what does Voltimand say has been done in response to King Claudius' letter to the King of Norway? 3. How does Claudius respond to what has been asked of him by Norway? 4. What does Polonius think is the cause of Hamlet's insanity? 5. What plan does Polonius come up with to test his theory? 6. Why do you think Hamlet behaves the way he does towards Polonius? 7. How does Hamlet act towards Rosencrantz and Guildenstern? 8. What does Hamlet ask the players (or actors) to do for him? 3.1 1. Who listens while Ophelia is sent to talk to Hamlet? 2. Describe Ophelia and Hamlet’s conversation, giving at least two quotes spoken by each person and an explanation of what those quotes mean and what they reveal about the entire conversation. 3. How do the “spies” react to the conversation they overhear? Do they think Hamlet’s madness was indeed caused by neglected love? What do they say? 3.2 1. What does Hamlet ask Horatio to do during the play? 2. How does Hamlet act towards Ophelia just before the play begins? 3. What do the players enact? How does Claudius react to this? What does Hamlet conclude? 3.3 1. What is the King concerned about at the beginning of 3.3? What does he plan to do to solve his “problem”? 2. Who plans to spy on Hamlet and Gertrude when Hamlet goes to speak to his mother? 3. In 3.3:36-72, what does Claudius do and say? What does it reveal to the audience? 3.4 1. Who does Hamlet kill while in his mother’s room? How does this murder occur? 2. What is Hamlet’s goal in talking to his mother? In other words, what does he want to accomplish? 3. Who unexpectedly interrupts Hamlet’s conversation with his mother after the murder has already occurred? How does the Queen react to this interruption? 4. How do you explain the different reactions from Hamlet and the Queen to the unexpected interrupter? 5. What instructions does Hamlet leave Gertrude with? 6. What does Hamlet reveal to Gertrude about Claudius’ plans for Hamlet and Hamlet’s plans to thwart them? 4.1 1. What does Gertrude tell Claudius about Hamlet 4.2 1. What do Rosencrantz and Guildenstern ask Hamlet? How does he respond? What does his answer mean? 4.3 1. What does Claudius say about Hamlet at the beginning of 4.3? 2. When Hamlet appears on the scene, what does he tell Claudius about the body? 3. Where does Claudius tell Hamlet he must go? Why does Claudius claim he is sending Hamlet there? What is Claudius’ real reason for sending Hamlet? 4.4 1. Who does Hamlet encounter at the beginning of 4.4? What does the captain reveal to Hamlet? 4.5 1. Describe what Ophelia does and how she acts from the beginning of 4.5 to 4.5:74. Does there seem to be any method in her madness? What does she do or say that may have an explanation? Explain. 2. What does the King think is wrong with Ophelia (4.5:75-97)? 3. Describe what Laertes does when he arrives on the scene (4.5:115-157)? 4.6 1. What does Hamlet say in his letter to Horatio? 4.7 1. After Claudius receives a letter telling of Hamlet’s return to Denmark, what plan do Claudius and Laertes agree to enact so that Laertes can revenge his father’s death? (4.7:128-164) 5.1 1. Describe how Hamlet reacts to Ophelia’s funeral. How does he act toward Laertes? What does this reveal about Hamlet’s feelings for Ophelia (do you think he truly loved her, or not?) 5.2 1. What is Hamlet’s explanation to Horatio about how he got back to Denmark? (5.2:12-55) 2. What does Hamlet say in his apology to Laertes? How does he explain his actions? Why should Laertes forgive Hamlet according to Hamlet? Give two quotes and explain them. (5.2:224-241) 3. What is Laertes response to Hamlet’s offer of apology and request for forgiveness? (5.2:242-250) 4. Describe how everyone dies. (You need to know the details of all the deaths in this scene) 5. What is the significance of Fortinbras finally showing up at the end of the play? Answer this question as specifically as possible, with as much detail as you can. Resistance to Civil Government by Henry David Thoreau Study Questions Part 1: The nature of government and of the individual 1. What distinction does Thoreau make between the US Government and the American people? (12) 2. With what does Thoreau say the individual should serve the state? (2-3) 3. What does Thoreau mean by the rule of expediency? What does this indicate about his views on the majority rules government versus the individual’s conscience? (1, 4-5) 4. What is Thoreau’s attitude toward voting? What does he advocate instead? (5) 5. What is a “man” (a person) according to Thoreau? What, according to him, is the nature of civil government? (3-6) Part 2: Combating Injustice 1. What options does Thoreau present the individual when confronted with unjust laws? Which of these options does he say is most preferable? 2. What does Thoreau mean by a “majority of one”? 3. What does Thoreau say would be the abolition of slavery in America? What does he mean by this? 4. What does Thoreau say about prison? Who belongs there? Why? How does Thoreau end up spending a night in prison? 5. What does Thoreau say about the relationship between money and virtue? Part 3: Thoreau’s Prison experience 1. How does Thoreau see his village from within the prison? How does he see his village once he is out of prison? 2. What kind of statement is Thoreau making by saying he prizes allegiance over money? 3. What does Thoreau mean when he says he wants to conform to laws? What would it take to get him to conform? 4. Do you agree with Thoreau that you have to be an outsider to see something (such as a system of government) objectively? Why or why not? 5. What is Thoreau’s final opinion/analysis of the government of his time? Enrichment article: Nederman, Cary, "Niccolò Machiavelli", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2009 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2009/entries/machiavelli/>. Niccolò Machiavelli Why Machiavelli? That question might naturally and legitimately occur to anyone encountering an entry about him in an encyclopedia of philosophy. Certainly, Machiavelli contributed to a large number of important discourses in Western thought—political theory most notably, but also history and historiography, Italian literature, the principles of warfare, and diplomacy. But Machiavelli never seems to have considered himself a philosopher—indeed, he often overtly rejected philosophical inquiry as beside the point—nor do his credentials suggest that he fits comfortably into standard models of academic philosophy. His writings are maddeningly and notoriously unsystematic, inconsistent and sometimes self-contradictory. He tends to appeal to experience and example in the place of rigorous logical analysis. Yet succeeding thinkers who more easily qualify as philosophers of the first rank did (and do) feel compelled to engage with his ideas, either to dispute them or to incorporate his insights into their own teachings. Machiavelli may have grazed at the fringes of philosophy, but the impact of his musings has been widespread and lasting. The terms “Machiavellian” or “Machiavellism” find regular purchase among philosophers concerned with a range of ethical, political, and psychological phenomena, even if Machiavelli did not invent “Machiavellism” and may not even have been a “Machiavellian” in the sense often ascribed to him. Moreover, in Machiavelli's critique of “grand” philosophical schemes, we find a challenge to the enterprise of philosophy that commands attention and demands consideration and response. Thus, Machiavelli deserves a place at the table in any comprehensive survey of philosophy. 1. Biography Relatively little is known for certain about Machiavelli's early life in comparison with many important figures of the Italian Renaissance (the following section draws on Grazia 1989 and Viroli 2000). He was born 3 May 1469 in Florence and at a young age became a pupil of a renowned Latin teacher, Paolo da Ronciglione. It is speculated that he attended the University of Florence, and even a cursory glance at his corpus reveals that he received an excellent humanist education. It is only with his entrance into public view, with his appointment as the Second Chancellor of the Republic of Florence, however, that we begin to acquire a full and accurate picture of his life. For the next fourteen years, Machiavelli engaged in a flurry of diplomatic activity on behalf of Florence, travelling to the major centers of Italy as well as to the royal court of France and to the imperial curia of Maximilian. We have letters, dispatches, and occasional writings that testify to his political assignments as well as to his acute talent for the analysis of personalities and institutions. Florence had been under a republican government since 1484, when the leading Medici family and its supporters had been driven from power. During this time, Machiavelli thrived under the patronage of the Florentine gonfaloniere (or chief administrator for life), Piero Soderini. In 1512, however, with the assistance of Spanish troops, the Medici defeated the republic's armed forces and dissolved the government. Machiavelli was a direct victim of the regime change: he was initially placed in a form of internal exile and, when he was (wrongly) suspected of conspiring against the Medici in 1513, he was imprisoned and tortured for several weeks. His retirement thereafter to his farm outside of Florence afforded the occasion and the impetus for him to turn to literary pursuits. The first of his writings in a more reflective vein was also ultimately the one most commonly associated with his name, The Prince. Written at the end of 1513 (and perhaps early 1514), but only formally published posthumously in 1532, The Prince was composed in great haste by an author who was, among other things, seeking to regain his status in the Florentine government. (Many of his colleagues in the republican government were quickly rehabilitated and returned to service under the Medici.) Originally written for presentation to Giuliano de'Medici (who may well have appreciated it), the dedication was changed, upon Giuliano's death, to Lorenzo de'Medici, who almost certainly did not read it when it came into his hands in 1516. Meanwhile, Machiavelli's enforced retirement led him to other literary activities. He wrote verse, plays, and short prose, penned a study of The Art of War (published in 1521), and produced biographical and historical sketches. Most importantly, he composed his other major contribution to political thought, the Discourses on the Ten Books of Titus Livy, an exposition of the principles of republican rule masquerading as a commentary on the work of the famous historian of the Roman Republic. Unlike The Prince, the Discourses was authored over a long period of time (commencing perhaps in 1514 or 1515 and completed in 1518 or 1519, although again only published posthumously in 1531). The book may have been shaped by informal discussions attended by Machiavelli among some of the leading Florentine intellectual and political figures under the sponsorship of Cosimo Rucellai. Near the end of his life, and probably as a result of the aid of well-connected friends whom he never stopped badgering for intervention, Machiavelli began to return to the favor of the Medici family. In 1520, he was commissioned by Cardinal Giulio de'Medici to compose a History of Florence, an assignment completed in 1525 and presented to the Cardinal, who had since ascended the papal throne as Clement VII, in Rome. Other small tasks were forthcoming from the Medici government, but before he could achieve a full rehabilitation, he died on 21 June 1527. 2. The Prince: Analyzing Power It has been a common view among political philosophers that there exists a special relationship between moral goodness and legitimate authority. Many authors (especially those who composed mirror-of-princes books or royal advice books during the Middle Ages and Renaissance) believed that the use of political power was only rightful if it was exercised by a ruler whose personal moral character was strictly virtuous. Thus rulers were counseled that if they wanted to succeed—that is, if they desired a long and peaceful reign and aimed to pass their office down to their offspring—they must be sure to behave in accordance with conventional standards of ethical goodness. In a sense, it was thought that rulers did well when they did good; they earned the right to be obeyed and respected inasmuch as they showed themselves to be virtuous and morally upright. It is precisely this moralistic view of authority that Machiavelli criticizes at length in his bestknown treatise, The Prince. For Machiavelli, there is no moral basis on which to judge the difference between legitimate and illegitimate uses of power. Rather, authority and power are essentially coequal: whoever has power has the right to command; but goodness does not ensure power and the good person has no more authority by virtue of being good. Thus, in direct opposition to a moralistic theory of politics, Machiavelli says that the only real concern of the political ruler is the acquisition and maintenance of power (although he talks less about power per se than about “maintaining the state.”) In this sense, Machiavelli presents a trenchant criticism of the concept of authority by arguing that the notion of legitimate rights of rulership adds nothing to the actual possession of power. The Prince purports to reflect the self-conscious political realism of an author who is fully aware—on the basis of direct experience with the Florentine government—that goodness and right are not sufficient to win and maintain political office. Machiavelli thus seeks to learn and teach the rules of political power. For Machiavelli, power characteristically defines political activity, and hence it is necessary for any successful ruler to know how power is to be used. Only by means of the proper application of power, Machiavelli believes, can individuals be brought to obey and will the ruler be able to maintain the state in safety and security. Machiavelli's political theory, then, represents a concerted effort to exclude issues of authority and legitimacy from consideration in the discussion of political decision-making and political judgement. Nowhere does this come out more clearly than in his treatment of the relationship between law and force. Machiavelli acknowledges that good laws and good arms constitute the dual foundations of a well-ordered political system. But he immediately adds that since coercion creates legality, he will concentrate his attention on force. He says, “Since there cannot be good laws without good arms, I will not consider laws but speak of arms” (Machiavelli 1965, 47). In other words, the legitimacy of law rests entirely upon the threat of coercive force; authority is impossible for Machiavelli as a right apart from the power to enforce it. Consequently, Machiavelli is led to conclude that fear is always preferable to affection in subjects, just as violence and deception are superior to legality in effectively controlling them. Machiavelli observes that “one can say this in general of men: they are ungrateful, disloyal, insincere and deceitful, timid of danger and avid of profit…. Love is a bond of obligation which these miserable creatures break whenever it suits them to do so; but fear holds them fast by a dread of punishment that never passes” (Machiavelli 1965, 62; translation altered). As a result, Machiavelli cannot really be said to have a theory of obligation separate from the imposition of power; people obey only because they fear the consequences of not doing so, whether the loss of life or of privileges. And of course, power alone cannot obligate one, inasmuch as obligation assumes that one cannot meaningfully do otherwise. Concomitantly, a Machiavellian perspective directly attacks the notion of any grounding for authority independent of the sheer possession of power. For Machiavelli, people are compelled to obey purely in deference to the superior power of the state. If I think that I should not obey a particular law, what eventually leads me to submit to that law will be either a fear of the power of the state or the actual exercise of that power. It is power which in the final instance is necessary for the enforcement of conflicting views of what I ought to do; I can only choose not to obey if I possess the power to resist the demands of the state or if I am willing to accept the consequences of the state's superiority of coercive force. Machiavelli's argument in The Prince is designed to demonstrate that politics can only coherently be defined in terms of the supremacy of coercive power; authority as a right to command has no independent status. He substantiates this assertion by reference to the observable realities of political affairs and public life as well as by arguments revealing the self-interested nature of all human conduct. For Machiavelli it is meaningless and futile to speak of any claim to authority and the right to command which is detached from the possession of superior political power. The ruler who lives by his rights alone will surely wither and die by those same rights, because in the rough-and-tumble of political conflict those who prefer power to authority are more likely to succeed. Without exception the authority of states and their laws will never be acknowledged when they are not supported by a show of power which renders obedience inescapable. The methods for achieving obedience are varied, and depend heavily upon the foresight that the prince exercises. Hence, the successful ruler needs special training. 3. Power, Virtù, and Fortune Machiavelli presents to his readers a vision of political rule purged of extraneous moralizing influences and fully aware of the foundations of politics in the effective exercise of power. The term that best captures Machiavelli's vision of the requirements of power politics is virtù. While the Italian word would normally be translated into English as “virtue,” and would ordinarily convey the conventional connotation of moral goodness, Machiavelli obviously means something very different when he refers to the virtù of the prince. In particular, Machiavelli employs the concept of virtù to refer to the range of personal qualities that the prince will find it necessary to acquire in order to “maintain his state” and to “achieve great things,” the two standard markers of power for him. This makes it brutally clear there can be no equivalence between the conventional virtues and Machiavellian virtù. Machiavelli expects princes of the highest virtù to be capable, as the situation requires, of behaving in a completely evil fashion. For the circumstances of political rule are such that moral viciousness can never be excluded from the realm of possible actions in which the prince may have to engage. Machiavelli's sense of what it is to be a person of virtù can thus be summarized by his recommendation that the prince above all else must acquire a “flexible disposition.” That ruler is best suited for office, on Machiavelli's account, who is capable of varying her/his conduct from good to evil and back again “as fortune and circumstances dictate” (Machiavelli 1965, 66). It is not a coincidence that Machiavelli also uses the term virtù in his book The Art of War in order to describe the strategic prowess of the general who adapts to different battlefield conditions as the situation dictates. Machiavelli sees politics to be a sort of a battlefield on a different scale. Hence, the prince just like the general needs to be in possession of virtù, that is, to know which strategies and techniques are appropriate to what particular circumstances. Thus, virtù winds up being closely connected to Machiavelli's notion of the power. The ruler of virtù is bound to be competent in the application of power; to possess virtù is indeed to have mastered all the rules connected with the effective application of power. Virtù is to power politics what conventional virtue is to those thinkers who suppose that moral goodness is sufficient to be a legitimate ruler: it is the touchstone of political success. What is the conceptual link between virtù and the effective exercise of power for Machiavelli? The answer lies with another central Machiavellian concept, Fortuna (usually translated as “fortune”). Fortuna is the enemy of political order, the ultimate threat to the safety and security of the state. Machiavelli's use of the concept has been widely debated without a very satisfactory resolution. Suffice it to say that, as with virtù, Fortuna is employed by him in a distinctive way. Where conventional representations treated Fortuna as a mostly benign, if fickle, goddess, who is the source of human goods as well as evils, Machiavelli's fortune is a malevolent and uncompromising fount of human misery, affliction, and disaster. While human Fortuna may be responsible for such success as human beings achieve, no man can act effectively when directly opposed by the goddess (Machiavelli 1965, 407-408). Machiavelli's most famous discussion of Fortuna occurs in Chapter 25 of The Prince, in which he proposes two analogies for understanding the human situation in the face of events. Initially, he asserts that fortune resembles “one of our destructive rivers which, when it is angry, turns the plains into lakes, throws down the trees and buildings, takes earth from one spot, puts it in another; everyone flees before the flood; everyone yields to its fury and nowhere can repel it.” Yet the furor of a raging river does not mean that its depredations are beyond human control: before the rains come, it is possible to take precautions to divert the worst consequences of the natural elements. “The same things happen about Fortuna,” Machiavelli observes, “She shows her power where virtù and wisdom do not prepare to resist her, and directs her fury where she knows that no dykes or embankments are ready to hold her” (Machiavelli 1965, 90). Fortuna may be resisted by human beings, but only in those circumstances where “virtù and wisdom” have already prepared for her inevitable arrival. Machiavelli reinforces the association of Fortuna with the blind strength of nature by explaining that political success depends upon appreciation of the operational principles of Fortuna. His own experience has taught him that “it is better to be impetuous than cautious, because Fortuna is a woman and it is necessary, in order to keep her under, to beat and maul her.” In other words, Fortuna demands a violent response of those who would control her. “She more often lets herself be overcome by men using such methods than by those who proceed coldly,” Machiavelli continues, “therefore always, like a woman, she is the friend of young men, because they are less cautious, more spirited, and with more boldness master her” (Machiavelli 1965, 92). The wanton behavior of Fortuna demands an aggressive, even violent response, lest she take advantage of those men who are too retiring or “effeminate” to dominate her. Machiavelli's remarks point toward several salient conclusions about Fortuna and her place in his intellectual universe. Throughout his corpus, Fortuna is depicted as a primal source of violence (especially as directed against humanity) and as antithetical to reason. Thus, Machiavelli realizes that only preparation to pose an extreme response to the vicissitudes of Fortuna will ensure victory against her. This is what virtù provides: the ability to respond to fortune at any time and in any way that is necessary. 4. Morality, Religion, and Politics These basic building blocks of Machiavelli's thought have induced considerable controversy among his readers going back to the sixteenth century, when he was denounced as an apostle of the Devil, but also was read and applied sympathetically by authors (and politicians) enunciating the doctrine of “reason of state” (Viroli 1992). The main source of dispute concerned Machiavelli's attitude toward conventional moral and religious standards of human conduct, mainly in connection with The Prince. For many, his teaching adopts the stance of immoralism or, at least, amoralism. The most extreme versions of this reading find Machiavelli to be a “teacher of evil,” in the famous words of Leo Strauss (1957, 9-10), on the grounds that he counsels leaders to avoid the common values of justice, mercy, temperance, wisdom, and love of their people in preference to the use of cruelty, violence, fear, and deception. A more moderate school of thought, associated with the name of Benedetto Croce (1925), views Machiavelli as simply a “realist” or a “pragmatist” advocating the suspension of commonplace ethics in matters of politics. Moral values have no place in the sorts of decisions that political leaders must make, and it is a category error of the gravest sort to think otherwise. Weaker still is the claim pioneered by Ernst Cassirer (1946) that Machiavelli simply adopts the stance of a scientist—a kind of “Galileo of politics”—in distinguishing between the “facts” of political life and the “values” of moral judgment. Thus, Machiavelli lays claim to the mantle of the founder of “modern” political science, in contrast with Aristotle's classical norm-laden vision of a political science of virtue. Perhaps the mildest version of the amoral hypothesis has been proposed by Quentin Skinner (1978), who claims that the ruler's commission of acts deemed vicious by convention is a “last best” option. Concentrating on the claim in The Prince that a head of state ought to do good if he can, but must be prepared to commit evil if he must (Machiavelli 1965, 58), Skinner argues that Machiavelli prefers conformity to moral virtue ceteris paribus. In direct contrast, some of Machiavelli's readers have found no taint of immoralism in his thought whatsoever. Jean-Jacques Rousseau long ago held that the real lesson of The Prince is to teach the people the truth about how princes behave and thus to expose, rather than celebrate, the immorality at the core of one-man rule. Various versions of this thesis have been disseminated more recently. Some scholars, such as Garrett Mattingly (1958), have pronounced Machiavelli the supreme satirist, pointing out the foibles of princes and their advisors. The fact that Machiavelli later wrote biting popular stage comedies is cited as evidence in support of his strong satirical bent. Thus, we should take nothing Machiavelli says about moral conduct at face value, but instead should understood his remarks as sharply humorous commentary on public affairs. Alternatively, Mary Deitz (1986) asserts that Machiavelli's agenda was driven by a desire to “trap” the prince by offering carefully crafted advice (such as arming the people) designed to undo the ruler if taken seriously and followed. A similar range of opinions exists in connection with Machiavelli's attitude toward religion in general, and Christianity in particular. Machiavelli was no friend of the institutionalized Christian Church as he knew it. The Discourses makes clear that conventional Christianity saps from human beings the vigor required for active civil life (Machiavelli 1965, 228-229, 330-331). And The Prince speaks with equal parts disdain and admiration about the contemporary condition of the Church and its Pope (Machiavelli 1965, 29, 44-46, 65, 91-91). Many scholars have taken such evidence to indicate that Machiavelli was himself profoundly anti-Christian, preferring the pagan civil religions of ancient societies such as Rome, which he regarded to be more suitable for a city endowed with virtù (Sullivan 1996). Anthony Parel (1992) argues that Machiavelli's cosmos, governed by the movements of the stars and the balance of the humors, takes on an essentially pagan and pre-Christian cast. For others, Machiavelli may best be described as a man of conventional, if unenthusiastic, piety, prepared to bow to the externalities of worship but not deeply devoted in either soul or mind to the tenets of Christian faith. A few dissenting voices, most notably Sebastian de Grazia (1989), have attempted to rescue Machiavelli's reputation from those who view him as hostile or indifferent to Christianity. Grazia demonstrates how central biblical themes run throughout Machiavelli's writings, finding there a coherent conception of a divinely-centered and ordered cosmos in which other forces (“the heavens,” “fortune,” and the like) are subsumed under a divine will and plan. Cary Nederman (1999) extends and systematizes Grazia's insights by showing how such central Christian theological doctrines as grace and free will form important elements of Machiavelli's conceptual structure.