Unit Two - Faculty

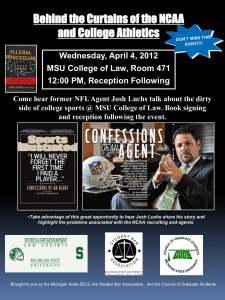

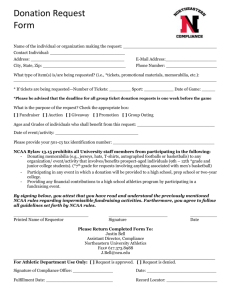

advertisement