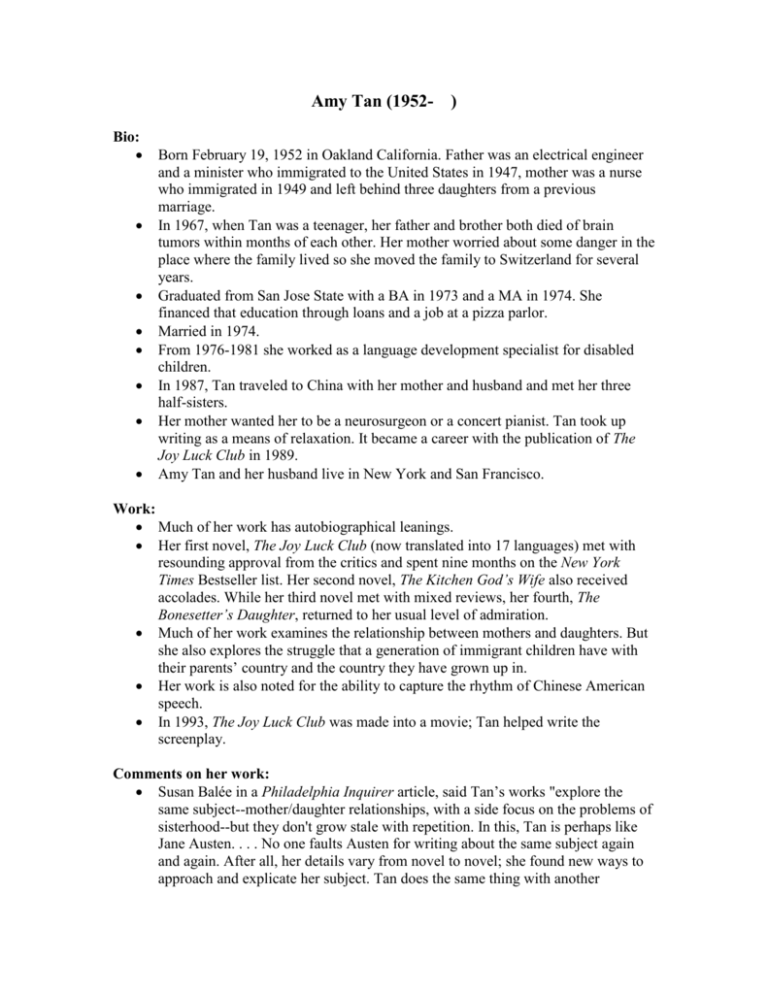

Amy Tan (1952- )

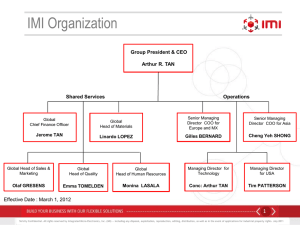

advertisement

Amy Tan (1952- ) Bio: Born February 19, 1952 in Oakland California. Father was an electrical engineer and a minister who immigrated to the United States in 1947, mother was a nurse who immigrated in 1949 and left behind three daughters from a previous marriage. In 1967, when Tan was a teenager, her father and brother both died of brain tumors within months of each other. Her mother worried about some danger in the place where the family lived so she moved the family to Switzerland for several years. Graduated from San Jose State with a BA in 1973 and a MA in 1974. She financed that education through loans and a job at a pizza parlor. Married in 1974. From 1976-1981 she worked as a language development specialist for disabled children. In 1987, Tan traveled to China with her mother and husband and met her three half-sisters. Her mother wanted her to be a neurosurgeon or a concert pianist. Tan took up writing as a means of relaxation. It became a career with the publication of The Joy Luck Club in 1989. Amy Tan and her husband live in New York and San Francisco. Work: Much of her work has autobiographical leanings. Her first novel, The Joy Luck Club (now translated into 17 languages) met with resounding approval from the critics and spent nine months on the New York Times Bestseller list. Her second novel, The Kitchen God’s Wife also received accolades. While her third novel met with mixed reviews, her fourth, The Bonesetter’s Daughter, returned to her usual level of admiration. Much of her work examines the relationship between mothers and daughters. But she also explores the struggle that a generation of immigrant children have with their parents’ country and the country they have grown up in. Her work is also noted for the ability to capture the rhythm of Chinese American speech. In 1993, The Joy Luck Club was made into a movie; Tan helped write the screenplay. Comments on her work: Susan Balée in a Philadelphia Inquirer article, said Tan’s works "explore the same subject--mother/daughter relationships, with a side focus on the problems of sisterhood--but they don't grow stale with repetition. In this, Tan is perhaps like Jane Austen. . . . No one faults Austen for writing about the same subject again and again. After all, her details vary from novel to novel; she found new ways to approach and explicate her subject. Tan does the same thing with another archtypal subject, and . . . like Austen, she will enjoy a secure place in the literary canon 200 years after the ink dries on the last page of her last book." In 1989 Tan told Susan Kepner three basic rules that Chinese mothers live by: "First, if it's too easy, it's not worth pursuing. Second, you have to try harder, no matter what other people might have to do in the same situation--that's your lot in life. And if you're a woman, you're supposed to suffer in silence." Other Resources: 1996 Interview with video and audio clips: http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/tan0int-1 1999 Salon interview: http://www.salon.com/12nov1995/feature/tan.html