Clergy perspectives on domestic violence

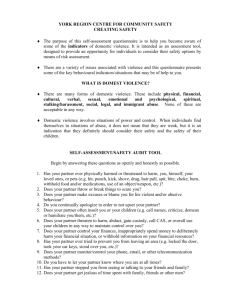

advertisement