Postmodern & Critique of Capitalism

advertisement

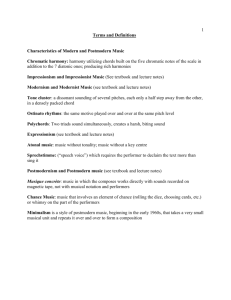

Act 1 Scene 5 Postmodern & Critique of Capitalism This scene is definitions of terms and concepts we will use in analyzing various Theatres of Capitalism. What is Postmodern? "Post" comes after modern (after bureaucracy, after hierarchy & after the industrial era). We are not yet postmodern, but we are making a postmodern turn. Best and Kellner (1997) call this "postmodern turn" a turn with two aspects, (1) the shift in modern to postmodern science knowledge and (2) a shift in aesthetics. For example, Palmer and Clegg (1996) define the postmodern organization aesthetic as one of "de-differentiation" as opposed to the division of labor of bureaucracy and an " incessant intertextuality," "infinite indexicality," and "open horizon" as opposed to the specificity of bureaucracy. In organization studies, there is much written about “postmodern organizations.” At one extreme the "radical" social constructionists version of postmodern theory is that all worldviews are social constructed and are also "arbitrary." The more "moderate" postmodern theory rejects the "arbitrary" or "relativistic" claim you can just "say anything." To the "moderate" postmodernist "everything is NOT "socially constructed." There are also "critical postmodernists" who accept the existence of "real" power structures and "material reality" who will not sit next to a "radical social constructionist." Before getting into critical postmodern, I want to start with what is a postmodern organization? What is a Postmodern Organization? Peter Drucker first used the term postmodern organization in 1957 in a book called Landmarks of Tomorrow. Peter Drucker, for example, sees management as going through paradigm shifts from the pre-industrial, industrial, to the postmodern or what he terms "post-business" era. The postmodern organization is defined, here, as a networked set of diverse, self-managed, self-controlled teams, an organization with many centers of coordination (poly-centered), that folds and unfolds. The ideal is a post-bureaucratic organization with a flatter hierarchy where employees are empowered to control their work, and information is shared so continuous improvement can be achieved. I know of no such organizations. Postmodern organization is also called loosely coupled, fluid, organic, adhocratic, or chaos organizations. Two points are being disputed widely in organization studies. First, the existence of postmodern organization is disputed. Second, there is widespread doubt that modern has been replaced by postmodern. Or even that we have ever been modern (Latour, 1993). Furthermore, the word is always being thrown into the middle of a fight, in a quarrel where there are winners and losers, Ancients and Moderns. 'Modern' is thus doubly asymmetrical: it designates a break in the regular passage of time, and it designates a combat in which there are victors and vanquished (Latour, 1993: 1). 1 The paradigm shift from premodern to modern, never finished off feudal, nor did the postmodern take over from modern (or premodern). I will argue we are still all three, in a process of hybridization (what below is a critical postmodern stance). As Rosenau (1992) theorized, some postmodernists make affirmative assumptions, and others make skeptical assumptions. The former ("affirmatives") posit that it is possible to move beyond exploitation by framing organizations in nonhierarchical and nonpatriarchical metaphors, such as webs and networks. Affirmative postmodern discourse elevates equality, democracy, ecology, and multiplicity and has roots in modern and even premodern models (Toulmin, 1990). There are affirmative postmodernists who see some possibility for modern organizations, skeptical postmodernist who do not believe in a postmodern organization (it is just late modern in disguise) and the critical postmodernist, who has a more moderate position. For example, reviews by Alvesson and Deetz (1996), Kilduff and Mehra (1997), and Hassard and Parker (1993) do not support the theory that there is any such entity as a postmodern organization. On the other end of the debate are those who contend that there are either hybrid or pure forms of postmodern organization, including Boje and Dennehy (1993), Clegg (1990), and Hirschman and Holbrook (1992). Various scholars see postmodern organization as a manifestation of "late modern" or "post-industrial" or "post-Fordism" or even "post-capitalism." These are all different. What is Post-Industrial? There are two views. The affirmative, post-industrialists argue that in the most recent industrial revolution smoke the traditional stake, brick and mortar organization is being replaced by a more virtual and service-business form. It is a form with fewer managers, where workers are gaining more autonomy to self-organize; the controlling and monitoring, once done by cadres of managers (and supervisors) is now being done electronically. The second view is more skeptical. The post-industrial firm has succumb to an age of "surveillance" (Foucault, 1977: 207, 221) because of the "need to maintain control of such aspects as promotion practices, wage scales and job categorizations has required the collection of "objective" data on employees, rather than relying on personal relationships" (Fairweather, 1999: 40-41). What is Post-Fordist? If Henry Ford symbolizes the "Fordist" factory model of mass assembly line production and mass consumption, then what is "Post-Fordism"? PostFordist is a more flexible and leaner (fewer workers) production system. Instead of mass production, small lots are produced with greater product variety to meet the tastes of different consumer groups. These consumer groups want products and services tailored to their unique needs. he new Post-Fordist firms exhibit a penchant for "flexibility" to meet demands of changing consumer demands and changing labor costs (i.e. cheaper labor in other parts of the world). Post-Fordist production also means continuous improvement processes, such as TQM (Total Quality Management), shorter cycle times (time it takes to change production line, invent a new product, change to meet new demands) and JIT (Just in Time Inventory) systems. The result is a flexible production system to meet the contingencies of fragmented markets. The skeptical view is the programs such as TQM result in more not less bureaucracy, the surveillance once performed by the micro- 2 managing supervisor, is now the internalized gaze and the employee micro-managing their performance quality. What is Post-Capitalism? There are three versions. First, Karl Marx (a definite modernists) envisioned a post-capitalist form of organizations that would be run by workers' councils. This cause was taken up in the trade union movement of the 1920s and 1930s and later continued by socialists antagonist to the capitalist model. The great worker revolt did not happen and state socialism collapsed with the former Soviet Union. There are two other approaches to consider. Second, for Peter Drucker (1991, 1993) competing in a global marketplace requires a new form of capitalism, what he terms "post-capitalism." In Drucker's version, "knowledge" is the key asset that managers and firms must manage and we are becoming a "knowledge society." We are going beyond brick and mortar and beginning to become virtual knowledge organizations, working in virtual teams, disseminating knowledge through web-based enterprises. In the new knowledge organizations, electronic technology with high-speed computer systems and automation are becoming common place. This is thought to be changing the very nature of capitalism. An entire consulting industry has sprouted over night to install systematic practices for managing a knowledge in the now postcapitalist enterprises. He views the post-capitalist organizations as innovative in tools, processes, products, work, and knowledge itself, designed for constant change. Of course, not everyone is convinced that there is a fundamental change or a post-capitalist organization, just the old wolf in new clothing. Third, a more recent approach to post-capitalism can be seen in the work of David Korten (1996a,b; 1999). He is calling for citizen participation in corporate governance. In this approach local communities could petition to have corporate charters revoked, particularly corporations that continue to do ecological and social damage. Numerous citizens, activist groups are beginning to take on corporate power. The recent demonstrations against WTO in Seattle and more recently against the World Bank are examples. But, there is also a growing "corporate charter" movement, which asserts that the founding fathers of the U.S. constitution had local control over corporate greed and mayhem. They argue that unbridled global capitalism is not always healthy for the local economy. In sum, Korten contends that multinational corporations use public relations spin control to mask themselves as responsible corporate citizens. But behind the PR mask are practices that pollute the natural environment, destroy labor markets, and exploit indigenous workers. 3 What is Late Modern? Organizations are in constant state of reform but they are still highly modern and even bureaucratic. The skeptical view is that there are fewer layers, fewer managers, and more talk of teams, but just late modern, not really postmodern. What it means to be a manager has changed in the "late modern world." Anthony Giddens (1991), for example, says that under conditions of 'late modernity', the construction and maintenance of managerial-identity is very problematic (see Casey, 1995). As institutional structures become destabilized and open to constant restructuring and revision, so 'self-identity becomes a reflexively organized project' (1991: 5). If a person's identity resides 'in the capacity to keep a particular narrative going' (Giddens, 1991: 54), when the institutional conditions in which viable narratives are constructed change, individuals may find their identities open to reformulation. As the possibilities for alternative identities and narratives emerge, the self enters a period of dislocation which offers the potential both for reaffirmation and transformation, and, since selves and institutions are dialectically related, the outcomes of personal struggles with identity manifest themselves in the identity of the occupation itself. So, for example, the reluctance of many managers to re-identify themselves as 'professionals' has inhibited the recasting of the occupation of management itself as a 'profession' (Reed and Anthony, 1992). [As cited in Danieli &Thomas, 1999: 449-450.] Is there a Dark Side to Postmodern Organization? My answer is Yes. In the postmodern turn, we simulate organizations, using concepts like "Virtual Organizations," where a core of a few full time people with total benefits lord it over the part timers, nobenefit sweatshop workers working for poverty wages throughout the world, and those net-slaves (cyber-commuting to work through computer hookup) also with no benefits at all. The dark side of postmodern virtual organizations is also the way in which Adam Smith’s ideal of an impartial spectator who would self-reflect on the Other, and empathize with the Other, has been all but defeated. In this book, we will look at the theatrics of McDonaldization, Disneyfication, and Las Vegasization. In this new postmodern theatre of capitalism, we will see the stage architecture of Disney and Las Vegas replacing the city center and even the modernist shopping mall. In Las Vegas, simulated New York, simulated Pairs, and simulated Venice are supposed to be safer, cleaner, easier, and more user-friendly than the real places which are too rude, crude, nasty and brutish. Answer the Question: Is there a Postmodern Organization? Call if postmodern, postindustrial, late-modern, or post-Fordist, is there one? Not in any pure form. A postmodern organization, by any name, would be a combination or collage of many types and forms (premodern, modern as well as postmodern), partly bureaucratic, partly chaotic, partly a quest to reform it all, and partly postmodern unknowability. The postmodern organization acts out fragmented and contrary scripts (script here is the story acted out in action). What is Critical Postmodern? Critical postmodern is the nexus of critical theory, postcolonialism, critical pedagogy and postmodern theory. "Critical postmodern 4 organization theory posits the increasing rationalization of organizational life as a threat to individual choice and well-being" (Feldman, S. 1999: 228). What is Critical Postmodern? My own stance on "spectacle" and "spectator," is critical postmodern (Best & Kellner, 1997) rooted in Guy Debord’s (1967) Society of the Spectacle. Critical postmodern is the nexus of critical theory, postcolonialism, critical pedagogy and postmodern theory. It is a growing field of study that is moving beyond the supposedly "radical postmodern" positions of Lyotard and Baudrillard by recognizing the interplay of grand narratives of modernity with the spectacularity of virtuality and hypercompetitiveness that is the basis of global predatory late modern and postmoderncapitalism, and the new forms transcorporate-empire, the postindustrial supply and distribution chains addicted to sweatshops, wedded to postmodern identity-formation through the age of virtuality and advertising, such that we no long discern real from phantasm. Radical postmodern theory is not a tautology, and we can explore the differences between many critical postmodernisms. Some postmodern theory is conservative and neo-liberal, so "radical postmodern theory" is not a tautology. (6-22001 conversation with Steve Best). My philosophical approach is critical postmodern theatre and narrativity, one that combines narrative ethics, critical dramaturgy, with critical postmodern theory (Boje, 1995, 2000). This means, I see myself as a consumer of narratives and corporate theatre, as complicit in the working conditions of labor in the global supply chain; I view my food choices as connected to the plight of animals in the food chain; and I view my life style as answerable to the world's need for sustainable choices (Boje, 2001a). I diverge from postmodern theories that seek to limit being to what is "socially constructed." Social construction theory (or interpretivism) is what many think of as postmodern, and that is dangerous, since it leaves out any consideration of the material conditions of the political economy. I prefer Debord to Baudrillard, and to combine Marx's focus on the material conditions with Guy Debord's (1967) Society of the Spectacle, as the basis of critical postmodern theory. Critical postmodern theory also argues that there is a material condition. The Holocaust did happen, genocide of indigenous people continues, as does the slaughterhouse of animal murder. The postmodern world is often quite a violent one, and I am answerable to try to minimize it, and not participate in it, and find a more festive path. It is time to move beyond the naive constructions of postmodern theory that are devoid of any discussion of the material conditions of Holocaust, slaughterhouse, post-11 war, and Enron. What is Critical Postmodern Theory? In a 'Critical Postmodern Manifesto' Boje, Fitzgibbons, and Steingard (1996: 90-1) argues that critical postmodern theory is about the "play of differences of micropolitical movements and impulses of ecology, feminism, multiculturalism, and spirituality without any unifying demand for theoretical integration or methodological consistency." "Critical postmodern" theory would recognize the multiplicity and multidimensionality that makes up our organizational and consumer experience 5 of ambiguity, conflict and discontinuity, and can inform more useful ways of working and thinking in this postmodern age (Boje, Fitzgibbons, and Steingard, 1996: 64). Critical postmodernism is theorized as a mid-range theory exploring the middle between "epoch postmodernism, epistemological postmodernism, and critical modernism" (p. 64). Critical postmodern theory is epochal in the sense that there is a postmodern turn (Best & Kellner, 1997) from modern to postmodern, but it is still in its infancy (Boje, Fitzgibbons, & Steingard, 1996: 64). Where there are "as yet, no postmodern organizations" there are examples of postmodern discourse embedded in the play of differences (Tamara) of premodern, modern, and postmodern discourses at Disney, as well as Nike (Boje, 1995, 2001b, c). And in the postmodern turn as well as the postmodern adventure of postmodern warfare in the Gulf War, and the new war on terrorism, we there is a dark side to postmodern, that is missed by non-critical approaches to postmodern (Best & Kellner, 2001; Boje, 2001d, e). I think it is possible to de-code the layers of public relations spectacle that heroize global virtual corporations (and since the 9-11, the global war machine), while distancing transnational corporations from responsibility over their far-flung global supply chains, where particularly exploitive conditions seem to flourish. Non-Critical Postmodern Approaches: There are many versions of postmodern theory. These range from the extreme positions of Baudrillard (rejecting real in favor of simulation and implosion), Lyotard (rejecting all grand narrative in favor of networks of local ones) to approaches by Best and Kellner (1991, 1997, 2001) that integrate the work of Marx and the spectacle writing of Guy Debord. The critical postmodern approaches incorporate a concern with how systems of ideas affect the material condition. For example in the Tamara Manifesto (Boje, 2001a), I am concerned with how we can explore the interplay of critical theory, critical pedagogy, and postcolonialism, and their relationship to critical narrative approaches. Other Approaches: Critical postmodern has a number of competing definitions and perspectives. Most include Marx and Nietzsche, but others are decidedly pomophobic (seeing the partnering of critical and postmodern as somehow responsible for all that is wrong with the world). In other words, postmodern has its affirmative and dark side. Postmodern casino resorts fashion a Paris, an Egyptian Pyramid, or a Venice more real than the real, and use Circus acts, street carnival, and the rides and exhibits of a Disney, as well as the mechanistic of McDonaldization to attract entire families to participate in gambling and sex addiction. In short, the postmodern has its dark side and is in strange hybridity with both modern factory, and pre-modern sweatshop and carnivalesque. 6 On the plus side, critical postmodern theory is a way to analyze the fractured and tortured lives of the voiceless who toil beneath the virtual glitz of Nike, Disney and Pairs, Paris. Critical postmodern theory is a way to get a clearer understanding of the relation between modern and postmodern, and take a Deleuzian journey into the middle of the hybridity of per-modern, modern, and postmodern (Boje, 1995). A critical postmodern project can move us beyond exploitation, racism, sexism, and abuse by reframing and restorying organization theory away from its patriarchal lingo in order to reaffirm social justice, equality, democracy, and the wonders of multiplicity (Boje, 1995: 1004). In a critical postmodern theory, such as Tamara, we can explore the 'micro-practices' of organizational life, as well as contextualize the stories of the marginal Other, within the workings of a postindustrial supply and distribution chain addicted to sweatshops, and the cover-stories produced and distributed by the postmodern storytelling organizations that turn out consumer identities and spectacles for mass consumption (Boje, 1995: 998-2). On the plus side, there is always resistance to the forces of global and individual domination and exploitation that stem from the strange hybridity of premodern, modern, and postmodern organizing amalgams. Critical postmodern theory is a rich variety of perspectives that do not accept the total rejection of the grand narrative such as in the work of Lyotard, nor do they abandon the material condition by being seduced into the vortex of hyper-real as in the work of Baudrillard. Rather, as Best and Kellner (1991, 1997, 2001) explore in critical postmodern philosophy, we are looking at a critical postmodern theory that is up to the task of exploring the postmodern turn that never transcends modern, and the postmodern adventure that in its darker manifestation protects predatory transnational corporations that pursue the Biotech Century at the expense of human life and biodiversity (2001: 1). My own project is to awaken the already seduced organization and management theory community of practice to the predatory global capitalism of McDonaldization, Disneyfication, and Las Vegatization. And this requires new forms of writing, and journals such as Tamara: Journal of Critical Postmodern Organization Science, that are prepared to say there is a material condition and a postmodern rampant consumerism as well as a predatory global capitalism, and pockets of resistance. Critical postmodern theory can also mean ways of deconstructing the post-11 war machine (Boje, 2001, d, e). Conclusions A critical postmodern manifesto resists the reduction of all postmodern theories into the camp of naive interpretativism or relativistic social construction. There is a beyond good and evil. There is a myth of Western capitalist Biotech progress. And there has not been a total displacement of premodern discourse by (systemic or critical) modern, or by (critical and uncritical) postmodern epochs, theories or praxis. History is in its grand narrative a three-act play of epochs, but in its material conditions, alternative histories (microstoria) is de-selected for mass consumption. Postmodern theory in it quest to vanquish systemic modernism, has ignored the contributions of critical postmodern and the dark side of the virtual postmodern hyperreality. We do not advocate the dismissive of all grand narratives, and we think that ethical standards can be worked out in networks of local discourse. As we said in 1996, in the Critical Postmodern Manifesto (Boje, 7 Fitzgibbons, & Steingard, 1996: 90-91), "Critical postmodernism is a radical disjunction from the systemic modernism discourse" of Taylorism, reengineering, and structural functionalism. Critical postmodernism is also "a play of differences of the micropolitical movements and impulses of ecology, feminism, multiculturalism, and spirituality without and unifying demand for theoretical integration or methodological consistency" (p. 90). Critical postmodern theory is a middle between critical modern, critical pedagogy, critical feminism, critical hermeneutics, critical-ethnomethod, critical-ecology, and postcolonial theories (p. 90-91). Instead of Baudrillard, we invoke Debord's analysis of the spectacle of late capitalism, and its Frankenstein marriage of postindustrial global supply chains with sweatshops, and the fetish of postmodern consumer identity formations facilitated by NikeTown, Disneyfication, McDonaldization, and Las Vegatization. The Holocaust did happen, the heroic story of Columbus is a fabrication of Washington Irving, animal slaughter is covered over by advertising by feminizing 'meat,' and the macho of carnivores, and it is time we unplug from the Matrix. 8