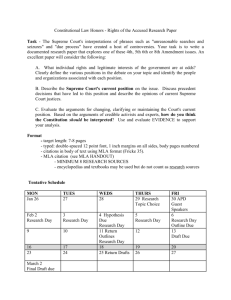

Criminal Procedure – Lerner.doc

advertisement