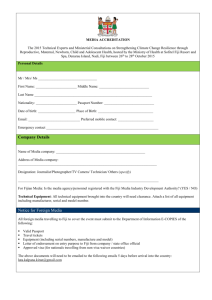

The Women`s Plan of Action 1999-2008

advertisement

The Women's Plan of Action 1999-2008. Volume 1 The Women's Plan of Action 1999-2008. Volume 2 Date: 1998 Source: The Women's Plan of Action 1999-2008. Ministry for Women and Culture. Suva, Fiji. The Ministry, 1998. 2v. ISBN 982-9007-01-4 Summary The Plan of Action is in two (2) volumes; the first volume contains directions for action required to achieve the broad Strategic Objectives of women and gender concerns/issues whilst the second volume contains the broad text outlines. The Women’s Plan of Action: Volume 1 Foreword CONTENTS INTRODUCTION PLAN OF ACTION FOR MAINSTREAMING WOMEN AND GENDER CONCERNS In summary the strategic objectives of the Plan of Action are to: Strengthen the Enabling Environment for women and gender mainstreaming; Develop and strengthen government processes to be gender responsive; Enhance sectoral and system wide commitment to mainstreaming women and gender; Engendering macroeconomic policies, national budgetary policies and procedures; Strengthen the institutional capacity of the Ministry of Women and Culture [National Machinery for Women] for women and gender policy advocacy and monitoring; Promote effective consultations of government bodies with key CSO's; and Integrate gender training in educational and national training institutions PLAN OF ACTION FOR WOMEN AND THE LAW In summary the strategic objectives of the Plan are categorized under seven broad headings: The law making process Access to justice Equal participation in political life Women and Labour Family Law Women and Health and Women and Education PLAN OF ACTION FOR MICRO-ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT In summary the strategic objectives of the Plan of Action are to: Build on supportive policy environment; Expand excess to micro-credit, particularly for women; Improve women's excess to formal credit through affirmative action; and Link credit facilities with enterprise development. PLAN OF ACTION FOR BALANCING GENDER IN DECISION-MAKING In summary the strategic objectives of the Plan of Action are to: To promote balanced gender representation in Boards, Committees, Council, Commissions and Tribunals; Strengthen women's accessibility to, and full participation in power structures and decision making; Create an enabling environment for equal opportunities in training, promotions, recruitment and appointments in the Public Service and encourage the same in the private sector. Create an enabling educational and social environment where equal rights of girls and boys, men and women are recognized and all, including special groups such as the disabled and immigrant women, are encouraged to achieve their full potential. PLAN OF ACTION FOR VIOLENCE AND CHILDREN In summary the strategic objectives of the Plan of Action is: To educate the community and law enforcement agencies to prevent and eliminate violence against women and children The Women’s Plan of Action: Volume 2: Foreword CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: MAINSTREAMING WOMEN'S AND GENDER ISSUES: Executive Summary, Overview, How Can Women's and Gender Concerns Be Maintained? Implementing Machinery: Executive Summary Previous efforts had sought to address the inequality between men and women through special programmes and projects for women. Mainstreaming on the other hand aims to integrate women’s concerns into the whole government system through a process of analysis of the different situation of men and women and thereby seeking to transform development processes towards greater gender sensitivity. In Fiji the situation of women is such that special programmes and projects for them are still necessary in order to accelerate the narrowing of the gender gap in many areas. However, during this process broader consideration for the transformation of our society to one that recognises and affirms equal rights of women and men, needs also to be taken into account. Throughout this Plan of Action, both approaches are considered necessary as implied in the use of both terms "women" and "gender". While the reference to "women’s concerns" recognises the need to focus on improving their specifically disadvantaged situation in society; the reference to ‘gender concerns issues’ reflects the resolve to address unequal relations between women and men resulting from socially and culturally determined gender roles. This gender inequality infiltrates all aspects of life including the tacit acceptance of violence against women in the home, unequal access to resources, skewed distribution in employment, decision-making and political participation. If both women’s concerns for equal participation and men’s rights to development are to be considered justly and to be integrated effectively into government’s decision-making processes, policies and programmes, decisionmakers must be provided with appropriate information, while planners and implementers must be equipped to build women’s and gender concerns into their activities. Overview The Government’s official planning and national strategy documents over the last 10 years have constantly expressed concern over the need to integrate women into planning process. Whilst women are represented at the district and divisional levels’ decision-making machineries where their concerns can be raised, a lot more needs to be done to ensure that they have effective representation, particularly at higher levels. At the sectoral and national levels, planners will need to undergo gender training to enable them to mainstream women’s issues and concerns. Social attitudes on gender roles continue to be deeply embedded in both genders and in the different cultural groups. This is reflected in the national indicators on the situation of women in the Fiji Islands. National statistics indicate that women are now al most just as well educated as men. Literacy for the younger citizens show no marked gender differences, school enrolments have equalized at both primary and secondary levels. In fact 1995 enrolment figures show girls comprising 48.6% of all primary level enrolments and a little over 50% of total enrolments through all classes form Forms 1 to 7 at secondary level. Female attendance at tertiary level institutions has also significantly increased. However, women still tend to dominate in the courses traditionally considered for females (nurses, secretaries, teachers etc.) while males still dominate course such as engineering and marine studies. Enrolments at the Fiji Institute of Technology in 1996 for example, for these male dominated fields showed less than 3% were females. On the other hand the enrolments for secretarial studies and for office administration were over 98% females. These statistics mirror prevailing attitudes on gender roles which will take a long time to change. According to the national health indicators, women’s health has significantly improved over the last 20 years. Maternal mortality rate for example dropped from 143 per 100,000 live births in 1975 to 34 per 100, 000 in 1994. Infant mortality rates more than halved from 41.4 to 16.3 per 1,000 live births during the same period. Nevertheless, there remains much room for improvement as patterns of mortality change with changes in lifestyle, and in women’s social situation. While maternal and infant mortality indicators show great improvements, increases in rate of lifestyle diseases such as diabetes, and different types of cancer are of concern. Available national economic statistics indicate that despite the great increases in educated women over the last 20 years, the proportion of males to female in the formal labour force has not changed significantly. Labour force participation rates show females comprised some 18.9% of the total labour force in 1985. This only increased slightly to 20.9% in 1992. Despite changes in patterns of economic development with greater income earning opportunities for women in the non-agricultural sectors such as garment manufacturing, women still concentrated in the lower waged jobs, and in the service sector. They are still largely involved in the informal economy with micro business enterprises, and in the subsistence economy. Their relative absence of female participation and input into the upper echelons of management in any sector, is a loss to the efficient running of the country as a whole an is of concern. A current initiative of the Fiji Islands’ government to create greater opportunities for employment for its people is to be introduced through the programme for Integrated Human Resource Development creation. The components of that programme include areas of particular concern to women. In addition, the Ministry for Labour has committed itself to initiate action to reflect in labour legislation women’s rights and also explore the ratification of ILO Conventions 100 and 111. The Government as a whole through the Public Service Commission has resolved to more effectively address the gender imbalance that currently exit in the Service and integrate women’s concerns in its employment systems. While the Fiji Island has a democratic system of Government the participation of different interest groups in the running of the country is variable. This is evident for women. Their representation on decision- making structures of various public and semi-public bodies is often minimal or altogether absent. The Fiji Islands’ Government resolution to achieve a 30% minimum participation of women in public decision-making bodies by 1998 has not been achieved. Participation of women on such bodies stood at a maximum of only 11% by 1996. The role of women in the Fiji Islands, as in many other countries has undergone marked changes as they continue to not only undertake their traditional role both in the informal and formal employment sectors. However, changes in cultural attitudes and practices have not kept pace, so that there is increasing stress not only on women but also on the family as a unit, contributing to the rise in youth delinquency and petty crimes. It is important that national policies address these concerns. WOMEN AND THE LAW. Executive Summary. Overview. The Law Making Process, Access to Justice. Equal Participation in Political Life, Women and Labour, Women and Family law, Women and Health, Women and Education. Executive Summary The law can accord or deny women equal rights. The principle of nondiscrimination on the basis of gender is guaranteed in the Constitution of the Fiji Islands as well as in a number of human rights conventions to which Fiji is a party such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. Guarantees of equality of rights cannot totally eliminate the natural differences between men and women; they can, however, attempt to eradicate unjust culturally- determined inequalities. Treating alike in all situations could also bring about inequalities as certain classes of persons require special treatment such as those with disabilities, children and young persons. Guarantees of equality would need to be balanced against their needs. The law is only one avenue to address the disadvantages and lack of opportunities faced by women. The law in itself could make fundamental changes that could bring about desired results, but the law cannot change overnight the ingrained customary practices that regulate the roles of men and women in society nor can it immediately change society’s assumptions and perceptions of women nor women’s assumptions and perceptions of themselves. It would take the coordinated efforts of law enforcement professionals, politicians, lawyers, physicians, the business community, the media educational institutions and NGOs to have an impact on the broad effects of discrimination against women. Women’s issues cannot be treated in isolation from their families and children. Families in Fiji have undergone dramatic changes in the last 30 years. The increase in single parent families, the rise in the divorce rates and the increasing number of women entering into cash employment have significant implications for the welfare of children and family life. One part of the strategy to deal with the welfare of children has been put in place by Government through the establishment of the Coordinating Committee on Children after ratifying the Convention on the Rights of the child. Fiji cannot afford to overlook the economic costs of absenteeism and reduced employee productivity of women through domestic violence. Women’s work in the subsistence sectors is not given formal recognition and therefore strategies for the protection and development of women through skills training and poverty alleviation and programmes to enhance women’s chances for participation in development would bring about a future that is less marred by gender biases and more respectful of human rights. Overview The law sometimes treats men and women differently and there are provisions in law in which a person’s sex makes the sole difference, as can be found in the laws relating to maternity benefits. Women usually cannot escape disabilities in the legal system, and in customary law of from discrimination imposed through governmental or commercial policies. The achievement or denial of legal rights to women is often an indicator of a country’s perception of the status of women and the role they play in national and community development. Any improvements in women’s legal status is often interpreted within the framework of equality with men. Such an interpretation can be fraught with difficulties because of the different roles men and women occupy in traditional societies. Where the law gives equal rights to men and women, customary rules, entrenched perceptions about women’s roles and community attitudes often prevent women from participating equally (1) In the last two decades, women’s issues have been in the spotlight at international and domestic levels. The "Development Strategies for Fiji: Policies and Programmes for Sustainable Growth" (December 1997) notes that improvements have been made to the commitments announced by the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing(1995) and obligations set out in the Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW Convention). In addition, in 1985 the Fiji Islands was party to the commitments made as the Nairobi Forward Looking Strategies for the Advancement for Women. These commitments and agreements consolidated principles at international levels in that mainstream human rights standards should be available to women as well as men on the basis of equality. All these international agreements strongly endorsed women’s rights as human rights and gender equality and equity in all sectors. The removal of negative stereotypes and attitudes, elimination of violence against women as well as other facets of discrimination, and of recognition of women’s contribution to society were all take into account. These commitments challenge the ability of the State to comply with the obligations. Historically, the Fiji Islands’ commitment to human rights treatise, go back to the time when the country was a British Crown Colony. Britain extended the application of a number of these treaties to the Fiji Islands such as International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Children 1921; Slavery Convention of 1926 and the 1953 Protocol; The Convention on Political Rights of Women 1954; Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery 1957; and The Convention on the Nationality of Married Women 1958. With the growing body of knowledge worldwide on women’s issues, the necessary translations and interpretations of international commitments to the local levels produced active research and a number of reports have been produced by the Ministry of Women and Culture, National Council of Women, Soqosoqo Vakamarama, the Fiji Women’s Rights Movement, the Fiji Women’s Crisis Centre, the Fiji Council of Social Services, the University of the South Pacific, the Regional Rights Resource Team and a number of other civil society organisations, identifying and analysing discrimination faced by women in the Fiji Islands. These reports define the principal legal issues and barriers facing women and the remedial measures to be taken to change and update existing laws, procedures and practices and recommending new laws that could effectively deal with problems faced by women. In practical terms, some laws are currently undergoing review and reform through the Fiji law Reform Commission. Women’s equality of rights and opportunities cannot be treated in isolation from their families and children. Families in the Fiji Islands have undergone dramatic changes in the last thirty years. The increase in single parent families and the high rate of divorce have a significant impact on the welfare of the children. Custodial parents are often the sole source of financial support and since that parent is often a mother with low income, the children are subjected to a childhood of poverty. One part of a strategy to deal with the welfare of children has been put in place by Government in establishing a Coordinating Committee on Children after ratifying the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1993. MICRO-ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT. Executive Summary. Overview. The Rational for Micro-Enterprise Development, the Critical Role of Finance, The Specific Disadvantage of Women, Current Forms of Support for MicroEnterprise Development, Current Lending Policies to Disadvantaged and Young Women, Making Present Systems of Credit more Accessible to Women, Improving Women's Access to Conventional Forms of Credit, Strengthening Micro-Credit Facilities, Developing Sustainable Micro-Credit Facilities, Developing a Sound Legal and Regulatory Environment for Micro-Credit, Linking Credit and Micro-Enterprise Development, The Women Flower Growers Nucleus Project. Executive Summary One of the five commitments made by the Fiji Government at the Fourth World Conference for Women held in Beijing, China in 1995, was to allocate additional resources to develop women’s micro-enterprises and encourage financial institutions to review their lending policies to disadvantaged women and young women who lack traditional sources of collateral. This Plan of Action follows up on this commitment by proposing ways in which existing facilities can be strengthened, describing the policies and institutional changes necessary to accomplish this, and setting out guidelines for microcredit facilities to operate in ways that are sustainable and promote small enterprise development. These proposals rest on several widely accepted understandings as to the economic and social value of increasing women’s involvement in economic enterprises and their access to the necessary credit facilities, in particular, the need for economic empowerment of women, their particular involvement in small-scale enterprises, and their special requirement for micro-credit. These proposals also rest on the analysis presented here of very limited facilities for credit in the Fiji Islands for small-scale borrowers and the restricted access of women to loans from formal financial institutions. They draw on lessons learned from micro-credit schemes in other countries, and make recommendations on ways to link credit provision with micro-enterprise development Overview Policy Support for Micro-credit and Micro-enterprise development There is a recognised need to create a supportive and legitimate environment for micro-credit and enterprise institutions to operate in the Fiji Islands, to: widen the availability of enterprise capital, especially to women; ensure these financial institutions operate within the national legal framework; and develop a supportive environment for small enterprise and selfemployment. This recognition is borne out in current and planned programmes of several ministries: The Ministry of Commerce, Industry, Co-operatives and Public Enterprises is planning to establish a National Centre for Small and Micro-Enterprise Development to provide technical advice, assistance and training for enterprise operators and conduct research into opportunities for small enterprises. The Ministry of National Planning, is strengthening resource planning to address unemployment issues and through the Integrated Human resource Development Programme, encourage small enterprise development. The Ministry of Women and Culture is responsible for the WOSED Programme and is committed to further develop women’s credit facilities and enterprises. The Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forests promotes small enterprise and self-employment in the primary industries but has new resources for enterprise development through the Commodity Development Fund (CDF). The Ministry of Fijian Affairs and ALTA provide special credit and technical support for Fijians and Rotumans to enter business and establish enterprises. Several international donor organisations are providing assistance in microcredit and micro-enterprise development either specifically for the Fiji Islands or in the Pacific region: NZODA provides various forms of support for micro-credit through NGO’s, revolving funds and development banks in several countries fo the region, including the WOSED Programme and the Fiji Development Bank New Zealand Small Loans Scheme in the Fiji Islands. In 1997, NZODA sponsored a regional conference to discuss lessons learned and best practices in micro-credit development assisting small enterprise development through various programmes and funds. UNDP, ILO and UNIDO are assisting small enterprise development through the Pacific Regional Small Enterprise Development Programme, which helps develop and enabling policy and support environment, including micro-credit facilities. UNDP’s Microstart Programme is a regional programme assisting the establishment and expansion of micro-credit facilities in the Fiji Islands, Marshall islands, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. Approximately USD600, 000 is earmarked for development for the Fiji Islands. AusAID is developing a Pacific regional micro-credit programme. World Bank will review donor experiences of micro-credit in the region, specifically the capacity of major micro-credit institutions for sustainability and outreach, their institutional capacity, and legal and regulatory frameworks. IFAD are considering the setting up of a Pacific Fund of USD5 million to be used by their members to establish or support micro-credit programmes. BALANCING GENDER IN DECISION-MAKING. Executive Summary, Overview, Sharing Decision Making- Ministerial Appointments, Nominated and Appointed Local Bodies, Elected Bodies, Public Service, Appointments., Addressing the Gaps, Acting to Balance Gander Against Participation in Decision-Making. Executive Summary The equal distribution of power and decision-making at all levels is essential to the empowerment of women. Government is committed to this and mechanisms need to be put in place and be vigorously applied if Government is to achieve its goal. Achieving the goal of shared decision-making between men and women will reflect the composition of society and strengthen the democratic processes of governance. It is also a necessary condition for women’s interests to be taken into account. Without the active participation of women and the incorporation of women’s perspectives at all levels of decisionmaking, the goals of equality, development and peace articulated in global women’s conferences will not be achieved. Overview Despite government’s clearly stated intentions to promote gender equality in development processes, participation of women in important public decisionmaking bodies remains minimal for most. Additionally gender participation in the upper echelons of the civil service continues to be skewed in favour of men. Although the equal rights of women to political participation is recognised in the Constitution of the Fiji Islands, this has not resulted in equal representation on decision-making bodies. Almost 20 years ago, in its 1980-1985 Development Plan, the government established a clear policy of integration of women as equal partners with men including their participation in employment and training. This resolve was reiterated in its Women and Development Policy stated in Development Plan I covering the period 1986 to 1990. In the latter plan the government not only determined to continue encouragement of the involvement of women as equal partners but also explicitly added that "furthermore, greater participation by women in decision and policy making bodies at the national level needs to be encouraged." These policies have continued to be part of government’s development strategies with additional refinements that show greater resolve to close the gender gap. In its 1993 policy document "Opportunities for Growth-Policies and Strategies for the Medium Term" the government committed itself to encouraging the involvement of women "through positive discrimination (where appropriate), and to making "further efforts to bring women more into the mainstream of management and decision-making." The 1995 Budget address stated that "Government recognises that an important aspect of improved status for women is their greater participation and involvement in decision-making processes at the national level. As such government will continue to assign 30-50% of representation of women on Boards and Committees as approved by Cabinet in June 1993 and will actively support the participation, training, appointment and promotions of women with merits and skills at all levels in both public and private sector." The same sentiments were restated in the 1996 Budget address. Further policy refinements were made by Cabinet. In June 1993, Cabinet urged appointing authorities to increase women’s membership in various Boards, Committees and Councils to reach 30%-50% during the period 1993-1998. In November 1996, Cabinet set the following guidelines for the appointment of Boards of Public Enterprises effective from 1st January 1997: " the numerical size of the Boards of Public Enterprises should be the stipulated quorum requirement plus up to three other members, with the overall size kept within a maximum total of seven members, and within this due consideration should also be given to ensuring a fair degree of gender balance." VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN AND CHILDREN. Executive Summary. Overview. Crimes of Violence, Domestic Violence, Common Forms of Domestic Violence in the Fiji Islands - Incest, Rape, Sexual Harassment, Sexual Offences Against Children and Child Abuse. Executive Summary Violence against women and children is a multifaceted problem. The law is one avenue which can be used to tackle the problem. Law reform in itself however is inadequate as supportive services and the training of care providers and law enforcement agencies are also necessary to ensure the protection of victims of violence and to expedite the process of justice for such victims. Ingrained bias against women and the stigma attached to victims of sexual violence are some of the obstacles to obtaining justice for women. Emphasis is therefore placed on the promulgation of specific laws to deal with violence against women and the improvement in law and practice to deal with child abuse cases. All of society has an interest in ending violence against women and children but it will never end unless we provide useful intervention. Direct services would need to be instituted to provide victims of violence with a safe haven, in urban and rural areas. The improvement in the data collection and analytical services would assist in designing strategies that extend far beyond the legal system, encompassing all aspects of society that deal with women and children. The training and up-skilling of service providers would all be significant steps to meet the stated goal of prohibiting violence against women and children. Overview Violence against women and children is the most pervasive violation of human rights and for women it is considered as a major impediment to their participation in development. Violence against women and children occurs at every level of society and has diverse forms. It ranges from explicit forms of violence such as wife beating, maiming, torture and rape to more covert acts such as regular use of abusive language and mental torture. Some forms of violence against women, particularly those that occur within the family, are entrenched and not recognized by society and our institutions as they are explained as "family discipline" and therefore ignored, condoned or tolerated. These social attitudes perpetuate violence and it requires more than punishment of the perpetrators to change these attitudes and behaviours. On the international level, the awareness of violence against women first emerged over two decades ago as a result of activism and research on issues related to the social status of women and their rights to participation in the total development process. Violence against women, as a major issue in Europe and North America, became visible during the early stages of feminist theory development. In other parts of the world, the convergences of development, human rights and feminist praxis produced the framework for addressing the nature forms, extent and pernicious effects of violence against women. It was the United Nations Decade for Women (1975-1985) that became the catalyst for international concerns on gender violence. Whilst the decade helped to focus attention on the critical importance of women’s activities for economic and social development, "women in development" also became the legitimate focus of research in action. International and local research identified the role played by women as mothers and wives as well as producers in the economic and subsistence sectors, which led many countries to focus their efforts on improving the status of women. Despite the efforts to integrate women in development, women remain only marginal participants in and beneficiaries of development and policy goals. Women continue to remain in a disadvantaged position in certain sectors such as employment and education. The process of change has been slow, but there is ample demonstration at the various levels that some advances have been made to bring about changes to improve the status and conditions of women and children. The UN Decade for Women and `Women in Development’ efforts, in general, have been successful in identifying problems critical to women’s participation that were not previously understood as development issues. One such problem area that has emerged is violence against women. This new alertness by women has also triggered a powerful ability at international and national levels to resolve them. The national recognition of the problem has been sow and although a variety of information emerged into the public sector through literature and media reports and there was sufficient evidence from the rising divorce rates and complaints of female assaults, violence against women as an issue remained unrecognised by society and law enforcement institutions for a complex of reasons. The major reason is that violence against women in frequently identified as a family matter that should remain in the private domain, in the belief that intervention would have an adverse effect on the family unit. In over two decades, as more reliable information began to emerge on the seriousness fo the issue, the United Nations and non-government organisations (NGO’s), religious organisations and other civil society groups initiated discussions on the ability of the law and law enforcement agencies to deal with the issue and on women’s vital roles in development. These discussions confirmed the disturbing conclusion that violence against women was a key impediment to their contribution to the vitality of the economy. Although awareness and acknowledgement emerged, the magnitude of the problem was still unknown due to the lack of statistical data. Despite this, Governments have determined that the problem is serious and that efforts must be made to bring abut changes to prevent and restrict these violations in more effective ways. Two suggestions for improvement have been made at international for a. in 1995, the World Summit for Social Development at Copenhagen suggested as follows: a. "Introducing and implementing specific policies and public health and social services programmes to prevent and eliminate all forms of violence in society, particularly to prevent and eliminate domestic violence and to protect victims of violence against women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities. In particular, the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women should be implemented and enforced nationally." b. "Taking full measures to eliminate all forms of exploitation, abuse, harassment and violence against women, in particular domestic violence and rape…" Also in 1995, at the 4th UN World Conference on Women in Beijing, the following statement was made by the Fiji Islands. "Campaigning to promote a sound and stable environment that is free of violence especially domestic violence, sexual harassment and child abuse." At the national level in the Fiji Islands, the prevalence of violence can only be understood in the context of its socio-economic milieu. A great deal of importance is placed on family relationships, which is generally defined by the caring and sharing attitude among the wide network of kin. This network of family relationships is seen as a social and economic safety net. However, the increasing social problems such as crime, drug abuse, poverty, and abuse of women and children indicate the changes occurring in the family. Perceptions with regard to the roles played by the family members where the husband and father occupies the role of head of the household have changed with the entry of women into the cash economy and the increasing numbers of females as heads of household. Although the dynamics that determine family relationships have changed, society continues to view violence against women and children as an encroachment into family privacy and family unity. There is therefore a deep rooted resistance to accepting violence in the home as an offence and violation of individual rights. Government is addressing the issues of violence and abuse through the Ministry of Education’s Family Life Education Programme and NGO’s in the private sector, such as the Lifeline Wesley Church, the Fiji Women’s Crisis Centre and the Fiji Women’s Rights Movement, YWCA and other religious organisations are also providing counseling services, family life education and support to victims. A number of factors affect improving the response to violence against women. Apart from the lack of knowledge and understanding of the dynamics of violent and abusive relationships, in order to devise strategies and methods to deal with the issue, studies have indicated that spousal abuse in the Fiji Islands is under-reported. According to one study "even with the massive underreporting of family related violence, the number or reported cases of domestic violence is high" (1). The high rate of under-reporting has been identified in the two studies (2) as being caused by the following factors: community and institutional attitude towards victims’ over perception of their situation; lack of access to information and services including police, legal representation and the court system; previous experience with service providers where interventions and outcomes were not helpful; no immediate legal assistance for victims; women’s perception of whether they will be delivered or supported and whether they believe there is likelihood of a positive outcome; fear of being homeless with no financial or emotional security; no immediate redress for perpetrators. These factors are by no means exhaustive as other factors can be added such as `no immediate place of safety available for the victims of violence, particularly in areas outside the urban sector’s. This is not to say that no shelters exist as the Salvation Army, Saint Christopher’s Home and Dilkusha, Mahaffy Girl’s Home and the Women’s Crisis Centre’s half-way houses are available to provide a safe haven for abused women. These problems can be further compounded for older women and women with disabilities. Economic dependency is another reason by women in the Fiji Islands, as elsewhere, have tolerated violence. It is estimated that women make up 30% of the total employment and are concentrated at the lower paid level. Statistics show that the government and the manufacturing sector are the largest employers of women. (Table 1 – not included) One quarter of all their opportunities is concentrated in traditional `women’s’ occupations: clerical, teaching, nursing, factory work and sales (UNICEF Report 1996). The Statistical Gender Profile of Fiji (1994) suggests that women are generally paid lower wages, rank lower in positions, and are less often promoted. The recent productive investments have concentrated on developing a low wage economy that has contributed to a decline in real wages while it has increased the number of women workers, some of these on wages and working conditions that are often labeled to be exploitative (UNICEF 1996). A large number of women are engaged in the informal sector, with many having lower paid jobs or unpaid jobs. It is clear that women in the Fiji Islands are subject to societal norms of being social and economic dependants of their male partners. Gender Impact Analysis must become an analytical tool for all planning and development processes in all public sectors, which will in the long term, assist in shifting societal attitudes. Document Title: National Report on the Implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action Source: National Report on the Implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action. [Suva, Fiji]. Ministry for Women and Culture, 1999. Date: 1999 Summary: The Report is set out in 3 Parts: Part 1 provides an overview of the major achievement that have been accomplished through the implementation policies, institutional strengthening and programmes; the predominant problems faced in certain sectors to achieve gender equality and the general trends towards achieving gender quality and the advancement of women. Part 2 sets out the Financial and Institutional Measures to implement the Fiji Islands on-going programmes to improve the status of women and the actions outlined in the Women's Plan of Action 1998-2008 which are generally consistent with the Beijing Platform for Action. Part 3 outlines the implementation of the 12 Critical Areas of Concern of the Beijing Platform for Action. It sets out innovative policies, programmes, projects and good practices; the obstacles encountered and commitments made for further action and the initiatives to be taken.