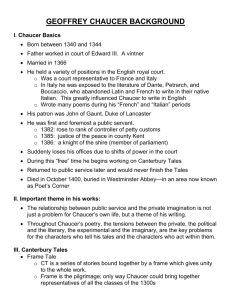

View/Open - Cadair Home - Aberystwyth University

advertisement