Banha University Faculty of Arts English Department A Guiding

advertisement

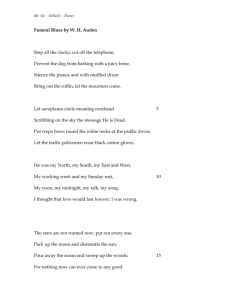

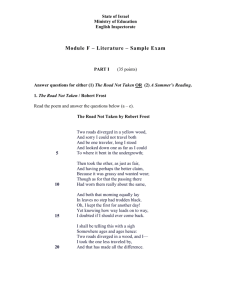

ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Banha University Faculty of Arts English Department A Guiding Model Answer for Modern Culture Second Level January 2011 Open Education Prepared by Mohammad Al-Hussini Mansour Arab, Ph.D. University of Nevada, Reno (USA) 1 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Banha University Free Education Department of English Second Level First Term (January 2011) Time Allowed: 3 hours Culture ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Respond to the following question: 1. Define modernism and state its major characteristics? Respond to only two of the following questions: 1. Analyze W. H. Auden's poem "Musée des Beaux Arts"? 2. Analyze Robert Frost's poem "The Road Not Taken"? 3. Discuss James Joyce's short story "Eveline" from a psychological perspective? Good Luck Mohammad Al-Hussini AbuArab 2 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Answers Part I Question # 1: Define modernism and state its major characteristics? Answer: Modernism, as a term, is often used to identify what is considered to be most distinctive in concepts, sensibility, form, and style in literature and art since the First World War. Most critics agree that it involves a radical break with the traditional bases of Western culture and art. The modernist revolt against literary forms and subjects manifested itself strongly after the catastrophe of World War I shook men's faith in the foundations and continuity of Western civilization and culture. The early years of the twentieth century produced three separate groups of poetic innovators: the Georgian poets, the Sitwell group, and the Imagists. The first group represents a break with the Imperial poetry of the same period, for it loosened the reins on traditional verse, and introduced the conversational diction and the simplicity of poetry. The work of the second group foreshadows the spiritual despair, the often-forced gaiety, the combination of wit and bleakness that show up in many other writers' work in the century. But their poetry had much surface but lacked substance. Of the three, Imagism is by far the most important school for modern verse at large. The goal of the movement was to bring to poetry a new emphasis on the image as a structural, rather than an ornamental, element. In "A Retrospect," the three cardinal rules of the movement are mentioned: direct treatment of the thing discussed; absolute economy of diction; and composition "in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in the sequence of the metronome." But the goals and techniques of the movement were antithetical to sustaining even a poem of any considerable duration. The tiny Imagist poem is much too limiting to allow its creator much variety from one poem to the next. The chance to explore themes, ideas, and beliefs simply does not exist. Though too restrictive to endure long, it proved to be the beginning of modern poetry. Almost every major poet up to this day has felt strongly the influence of the Imagist experiments with precise, clear images, juxtaposed without expressed connection. Perhaps, the single most important influence has been nineteenth century French symbolism. What was fresh and unique was the insistence of the symbolists on the symbol as the structural raison d’être of the poem. In fact, they were reacting against the loose, discursive verse as well as, the allegorical and didactic verse. They also mistrusted language and placed heavy emphasis on the poetic moment, the symbol. Although there were three sources of importation, the outstanding importer of symbolism was Eliot, whose, The Waste Land, demonstrates its creator's overwhelming debt to the symbolists, which is 3 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ apparent in the use of urban landscape, the feverish, nightmarish quality of the imagery, the darkness of the vision, the layering of symbols and images within symbols and images. Another example of Eliot's importance is the resurrection of the English Metaphysical poets as models for modern verse. Long ignored by English critics, the Metaphysical poets offer the modern poet another use of a controlling metaphor. The conceit of the Metaphysical poem, like the symbol of the symbolist poem, is an example of figurative language used as structural principle. Since the conceit of a Donne poem is used as a way of integrating metaphor with argument, the model served to overcome the limiting element of Imagism and, to a lesser extent, of symbolism itself. Both the latter movements, since they eschewed argument as a poetic method, shut themselves off from the possibility of sustained use. The Metaphysical conceit, also, allows Eliot to adapt Imagist and symbolist techniques to a long, elaborately structured poem. Another, very different model for long poems was found in Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass. His great contribution is in the area of open form, which has done more than anything else to show the path away from iambic verse. By the end of World War II, the poetics of impersonality and detachment as sponsored by Eliot suddenly seemed outmoded, and the movement in much of modern poetry since that time has been toward a renewed involvement with the self with its flaws, hungers, and hidden violence. This led to what is to be called "confessional poetry" which appears in the poems by Emily Dickinson. The interest in Dickinson leads to a new involvement with the darker side of Romanticism, as well as the buoyant optimism as shown in the poems of Lawrence and Whitman. Another branch of postwar American and English poetry has been heavily influenced by surrealism, which has been imported into American poetry through the work of Bly, and Wright, whose "deep image" poetry often reads like a symbolist rendering of deep consciousness. Another distinctive characteristic of modern poetry is its preoccupation with myth and archetype. Among the fruits of this trend were the two most important works produced in English in this century, James Joyce's Ulysses (1922) and T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land. Joyce's work recounts the story of a single day in Dublin in 1904, during which the ramblings of an Irish Jew parallel the wanderings chronicled in the Odyssey (c. 800 B.C.). In his essay "Ulysses, Order, and Myth," Eliot announced that in place of the traditional narrative method, the modern artist could henceforth use the mythic method, that fiction and poetry would gain power not from their isolated stories, but through the connection of the stories to a universal pattern. This is exemplified in James Frazer's book The Golden Bough and the works of Sigmund Freud and Carl G. Jung. A final defining characteristic of modern poetry is its ambivalence. Yeats provides an elaborate image of that ambivalence with his "whirling gyres." In Yeats, one idea is never whole; it must have its opposite idea. The most famous example of Yeatsian 4 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ ambivalence, mirroring the pair of gyres, is a pair of interlocking poems about Byzantium. In "Sailing to Byzantium," the old speaker seeks the tranquility of the artificial world represented by Byzantium. In "Byzantium" he looks back to the world of flesh and mire. The Byzantium poems embody a fundamental feature of modern poetry: the chaos of the modern world which leads the poet's desire retreat into the sheltered world of aesthetics. His desire to retreat and not to retreat forms ambivalence. In general, modern poetry may be characterized fairly as the poetry of ambivalence. In turn, much of the attitudinal bias of the New Criticism can be explained on the basis of ambivalence: the emphasis on irony, tension, ambiguity, as keys to poetry; the elevation of the Metaphysical poets and the concomitant devaluation of Romantic and Victorian verse; the blindness to poetry that is open or single-minded. Despite its shortcomings, the New Criticism's great contribution was that it taught readers, and still teaches them, how to read modern poetry. Part II Question # One: Analyze W. H. Auden's poem "Musée des Beaux Arts"? Answer: W. H. Auden's "Musée des Beaux Arts" is a poem about the universal indifference to human misfortune. Following a series of reflections on how inattentive most people are to the sufferings of others, the poet focuses on a particular interpretation of his theme: a sixteenth century painting by the Flemish master Pieter Brueghel, the Elder, called The Fall of Icarus. It contemplates the nature of suffering and transcendence through reference to Pieter Breughel's painting The Fall of Icarus, which the poet had perhaps seen on a trip to Brussels. In Greek mythology, Icarus and his father Daedalus had escaped from the labyrinth by crafting wings made of wax. Icarus in his sense of exhilaration at his escape dared to climb higher and higher in the sky until the sun melted his wings and he plunged to his death. Breughel's painting shows the moment when the youth hits the water, his legs barely visible in the remote distance in the right hand corner of the painting. In the center of the canvas is the ploughman who either does not hear the splash of Icarus' fall over the snort of his plough horse or ignores the event, too involved in his daily affairs to bother about such a miraculous event. Auden's poem begins by contemplating the nature of suffering, recalling the "Old Masters," presumably those Dutch religious painters who portrayed sacred events in the garb of contemporary Antwerp or Brussels. Many such canvases represented miraculous events from Scripture occurring amidst the hustle and bustle of city streets, a fact which sparks Auden's imagination. Suffering, he speculates, "takes place / While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along." He elaborates upon this truth and 5 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ attempts to mildly shock his readers by his use of vulgar language: "even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course / Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot / Where the dogs go on with their doggy life." Naturally Auden was keenly aware that the central events in Christ's life were surrounded by the banal and the everyday—he was born in a stable, surrounded by tax collectors and fishermen, and died with Roman soldiers marching underneath the Cross. Part of Auden's intention is to satirize the bourgeois smugness of a Europe on the brink of war—the poem dates from 1938, months before Hitler's troops invaded Poland—but the poem would not capture one's imagination if it had remained simply an attack upon middleclass thick-headedness and insensitivity. Ultimately, the crude language is abandoned in favor of an elegant simplicity, as if affirming paradoxically the simple faith of common folk and the pathos of everyday suffering: "the ploughman may / Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry, / But for him it was not an important failure." Auden's image remains ambiguous, caught between his own revulsion at humanity's blindness to suffering, and his admiration for their strong, stoic endurance of suffering itself. The poem is an example of ekphrasis, the embedding of one kind of art form inside another, because it summarizes a famous painting. Brueghel's The Fall of Icarus captures the final moment of an elaborate and portentous Greek myth. In his interpretation, the disappearance of the imprudent boy is not the center of the viewer's attention, just as it passes unnoticed by everyone else within the frame. Like Brueghel, Auden would force one to take notice of universal disregard. Thus, the poem questions the ability of art to matter in a world of intractable apathy. Not only is Daedalus rendered powerless, but the horrendous death of his son Icarus passes unheeded and unmourned. Even the sun, which, by melting the wax wings, is most directly responsible for the catastrophe, shines without pause or compunction. Question # Two: Analyze Robert Frost's poem "The Road Not Taken"? Answer: By Frost's own account, he wrote "The Road Not Taken" as ironic commentary on his friend Edward Thomas's Romantic nature. Biographical studies have held that Frost and the British poet often went walking in the English countryside and, on more than one occasion, Thomas expressed regret that they must choose one road over another. The poem begins with a sense of division and fragmentation—the speaker betrays a sense of being alienated from himself, and a feeling that the choice he is faced with will divide him further: "sorry I could not travel both / And be one traveler, long I stood / And looked down one as far as I could / To where it bent in the undergrowth." From his wordchoices, Frost appears to gaze into the woods, perhaps symbolic of his own unconscious, for knowledge, only to abandon himself to chance when no knowledge is forthcoming, 6 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ when nothing appears to make one path more attractive than the other. The two paths to his mind's eye become equals—"both that morning equally lay / In leaves no step had trodden black." In these woods the poet seems to imagine an Edenic paradise, not yet blackened by sin, but that evocation seems mainly ironic, as the final lines of the third stanza indicate that the narrator is aware of humanity's fall from grace, and of his own exile from the paradise he sees before him: "Yet knowing how way leads on to way, / I doubted if I should ever come back." The choice is final and irreversible, as "way leads on to way," yet the reason to choose one path over the other remains undisclosed. The woods do not yield their secrets, and the narrator, left prey to his own irrational whim, must choose one path over the other without any useful knowledge of what lies ahead on either. The final stanza, while often read as a tribute to self-reliance, suggesting a break with social conventions, also seems to dramatize a self-deception in the speaker. The first two lines are sentimental and self-congratulatory, a fantasy of bragging to one's offspring of virtue and self-mastery, of striking out on one's own to be a trailblazer—"I shall be telling this with a sigh / Somewhere ages and ages hence." The break in the third line, the "Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—," seems to have the speaker poised at the edge of authentic self-revelation, of truly understanding why he will choose one path. Ultimately it does not come, however, and he reverts to the comfortable fiction of self-reliance, suggesting that his choice, though made essentially at random, has a profound significance: "I took the one less traveled by, / And that has made all the difference." So, this poem which has been read over the decades as a validation of self-reliance and individuality, is also, or is perhaps primarily, a portrayal of humanity's self deception in the face of cosmic abandonment and difficult choices, the true significance of which is forever beyond our grasp. The prevailing theme of Frost's "The Road Not Taken" is individualism. The traveler is alone and must face this difficult choice alone. Both roads seem very similar, and their differences may only be subjective. The traveler cannot go in both directions because he is but one person. The tension in the poem is provided by the individual's interaction with nature, which combines a sense of wonder at the beauty of the natural world with a sense of frustration as the individual tries to find a place for himself within nature's complexity. Romanticism is another theme of "The Road Not Taken." Frost has made it clear in his essays and letters as to the origins of this poem and its inherent ironic nature as it pokes fun at the Romantic character of his close friend Thomas. Many critics still maintain that "The Road Not Taken" does not just describe another man's Romantic nature but also bears traces of Frost's own Romantic influences. Frost's debt to Romanticism is readily apparent in this poem, but is mitigated by his own ironic interpretation of the work. 7 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Question # Three: Discuss James Joyce's short story "Eveline" from a psychological perspective? Answer: On either side of Eveline's major life decision about whether to leave her home is a suspect and potentially abusive man. Because of the manner in which Joyce has set up the story, however, she must choose one of them; and due in large part to what is probably the result of years of psychological and physical abuse, Eveline pictures both of these men as her potential protector. She seems to be searching for a tender father figure; somewhat illogically, she tries to balance her father's increasing capacity for violence by remembering three random acts of gentleness. And she pictures Frank in a similar way, as a savior and protector to "take her in his arms, fold her in his arms," repeating as if to convince herself that "he would save her." According to Freud, attraction to a parent of the opposite sex and rivalry with the parent of the same sex represents an extremely important developmental stage for children. Psychoanalysis attributes much abnormal psychology in later life to a failure to successfully emerge from this role, highlights its prevalence in dreams and in primitive societies, and ultimately concludes that it is a central conflict for all of human psychology. Freud began with some ambiguity about the distinction between boys and girls in their enactment of the Oedipal drama, but as his 1916 "Development of the Libido and Sexual Organizations" lecture clarifies, he considered that things proceed in just the same way, with the necessary reversal, in little girls. The loving devotion to the father, the need to do away with the superfluous mother and to take her place, the early display of coquetry and the arts of later womanhood, make up a particularly charming picture in a little girl, and may cause us to forget its seriousness and the grave consequences which may later result from this situation. Grave consequences indeed follow for Eveline, in whom the reader notices the key symptoms of an Oedipal complex: major problems in adult sexuality that relate to her parents. Joyce seems to be implying that Eveline has failed to emerge from a childhood attraction to her father, which is a vital element in Freud's analysis of the complex, in a number of ways. First, Joyce makes it clear that Eveline has a rather ungrounded attraction to her father when she says, "Sometimes he could be very nice," and remembers three instances of his tenderness. In fact, it is particularly interesting that Mr. Hill puts on his wife's bonnet because it was an important belief of Freud's that pre-pubescent girls are first attracted to their mothers before they begin their more prolonged attraction to their fathers. Secondly, there is Eveline's fondness for her brothers, although they have disappeared as possible incestuous partners (consider Freud's remarks later in "Development of the Libido and Sexual Organizations" that incestuous partners are a 8 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ detriment to emergence from the Oedipal complex: "A little girl takes an older brother as a substitute for the father who no longer treats her with the same tenderness as in her earliest years.") The fact that Harry and Ernest have departed from Eveline's life would imply, in Freudian terms, that she is now freer to find a non-incestuous, although father-like, sexual partner. For Freud, the only possibility of successful escape from the Oedipal drama is with a father-like lover that will eventually lead the female child to what Freud would consider "normality," or what Eveline might mean by "life." Of course, this lover is Frank; as has already been established, Eveline treats her lover as another version of her father, a new father that will protect her and "perhaps love" her but, more importantly, "give her life." Perhaps the most convincing evidence that "Eveline" can be read as a Freudian Oedipal drama, however, is the influence of Mrs. Hill on the story. Eveline has taken her mother's place in exact parallel to Freud's theory. She acts as her father's housewife to the point where even Mr. Hill associates her with his late wife when he becomes abusive toward her: "latterly he had begun to threaten her and say what he would do to her only for her dead mother's sake." There is a perverse sense in this phrase, and throughout the story, that sex is always related to a violent exchange of property, that intercourse itself is implied in what he would "do to her." Confrontational with her mother's ghost but unable to disregard the promise to fulfill her duty, "keep the home together," and inhabit Mrs. Hill's own doomed role (including her nervous breakdown), Eveline is condemning herself to a life of Oedipal inhibition. Joyce supports this idea, which many critics have termed Eveline's "paralysis," with sophisticated symbolism. The author is by no means straightforward in his implication that Eveline has failed to successfully emerge from her Freudian conflict via its only solution, her lover. Many suspicions about Frank's character are implied in the text, including his symbolic association with exile and questionable morality, since Buenos Aires was associated with prostitution and the "Patagonians" he describes were notorious for their barbarity. Also, the night boat journey from the "North wall" may be a reference to the mythological voyage through the river Styx to the Underworld and therefore Eveline's death (as opposed to the "life" of psychological normality she seems to desire). But the main force of the symbolism in the story, including the sea as spiritual regeneration and baptismal font, is Ireland as Eveline's mother finally sees it: "Derevaun Seraun" (which probably means something like "worms are the only end" and certainly connotes terrifying oppression). Take the climax of Eveline's psychosexual development: --Come! All the seas of the world tumbled about her heart. He was drawing her into them: he would drown her. She gripped with both hands at the iron railing. --Come! No! No! No! It was impossible. Her hands clutched the iron in frenzy. 9 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Examined from the Freudian lens it is clear that this orgasm is Frank's, and that Eveline's is denied; instead of "Yes! Yes! Yes!" she experiences "No! No! No!" The orgasmic seas of the world, she feels, will drown her, so she grips the phallic alternative to Frank, the iron railing that echoes the first image of her father's "blackthorn stick." It is no surprise that, like her mother, gripping this iron railing representing Mr. Hill sends Eveline into a "frenzy" that reminds us of her palpitations and her mother's nervous breakdown. Eveline has, in Freudian terms, become entirely frigid and failed to escape from the prison of her own psychology. The only method of emergence from the Oedipal complex, despite his suspect intentions and his own orgasm seeming to drown Eveline, is Frank, so it is no surprise that the final imagery of the story is one of suppression and regression to extreme infancy: "She set her white face to him, passive, like a helpless animal." Joyce is at one of his bleakest moments here, envisioning almost hopeless psychological oppression as Eveline is unable to break free of her abusive father. 10