Grammar

advertisement

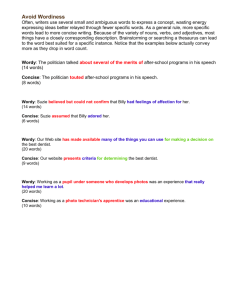

GRAMMAR: TRANSITIONS AND TRANSITIONAL DEVICES Writing Transitions Good transitions can connect paragraphs and turn disconnected writing into a unified whole. Instead of treating paragraphs as separate ideas, transitions can help readers understand how paragraphs work together, reference one another, and build to a larger point. The key to producing good transitions is highlighting connections between corresponding paragraphs. By referencing in one paragraph the relevant material from previous ones, writers can develop important points for their readers. It is a good idea to continue one paragraph where another leaves off (instances where this is especially challenging may suggest that the paragraphs don't belong together at all.) Picking up key phrases from the previous paragraph and highlighting them in the next can create an obvious progression for readers. Many times, it only takes a few words to draw these connections. Instead of writing transitions that could connect any paragraph to any other paragraph, write a transition that could only connect one specific paragraph to another specific paragraph. Example: Overall, Management Systems International has logged increased sales in every sector, leading to a significant rise in third-quarter profits. Another important thing to note is that the corporation had expanded its international influence. Revision: Overall, Management Systems International has logged increased sales in every sector, leading to a significant rise in third-quarter profits. These impressive profits are largely due to the corporation's expanded international influence. Example: Fearing for the loss of Danish lands, Christian IV signed the Treaty of Lubeck, effectively ending the Danish phase of the 30 Years War. But then something else significant happened. The Swedish intervention began. Revision: Fearing for the loss of more Danish lands, Christian IV signed the Treaty of Lubeck, effectively ending the Danish phase of the 30 Years War. Shortly after Danish forces withdrew, the Swedish intervention began. Example: Amy Tan became a famous author after her novel, The Joy Luck Club, skyrocketed up the bestseller list. There are other things to note about Tan as well. Amy Tan also participates in the satirical garage band the Rock Bottom Remainders with Stephen King and Dave Barry. Revision: Amy Tan became a famous author after her novel, The Joy Luck Club, skyrocketed up the bestseller list. Though her fiction is well known, her work with the satirical garage band the Rock Bottom Remainders receives far less publicity. Transitional Devices 1 Transitional devices are like bridges between parts of your paper. They are cues that help the reader to interpret ideas a paper develops. Transitional devices are words or phrases that help carry a thought from one sentence to another, from one idea to another, or from one paragraph to another. And finally, transitional devices link sentences and paragraphs together smoothly so that there are no abrupt jumps or breaks between ideas. There are several types of transitional devices, and each category leads readers to make certain connections or assumptions. Some lead readers forward and imply the building of an idea or thought, while others make readers compare ideas or draw conclusions from the preceding thoughts. Here is a list of some common transitional devices that can be used to cue readers in a given way. To Add: and, again, and then, besides, equally important, finally, further, furthermore, nor, too, next, lastly, what's more, moreover, in addition, first (second, etc.) To Compare: whereas, but, yet, on the other hand, however, nevertheless, on the contrary, by comparison, where, compared to, up against, balanced against, vis a vis, but, although, conversely, meanwhile, after all, in contrast, although this may be true To Prove: because, for, since, for the same reason, obviously, evidently, furthermore, moreover, besides, indeed, in fact, in addition, in any case, that is To Show Exception: yet, still, however, nevertheless, in spite of, despite, of course, once in a while, sometimes To Show Time: immediately, thereafter, soon, after a few hours, finally, then, later, previously, formerly, first (second, etc.), next, and then To Repeat: in brief, as I have said, as I have noted, as has been noted To Emphasize: definitely, extremely, obviously, in fact, indeed, in any case, absolutely, positively, naturally, surprisingly, always, forever, perennially, eternally, never, emphatically, unquestionably, without a doubt, certainly, undeniably, without reservation To Show Sequence: 2 first, second, third, and so forth. A, B, C, and so forth. next, then, following this, at this time, now, at this point, after, afterward, subsequently, finally, consequently, previously, before this, simultaneously, concurrently, thus, therefore, hence, next, and then, soon To Give an Example: for example, for instance, in this case, in another case, on this occasion, in this situation, take the case of, to demonstrate, to illustrate, as an illustration, to illustrate To Summarize or Conclude: in brief, on the whole, summing up, to conclude, in conclusion, as I have shown, as I have said, hence, therefore, accordingly, thus, as a result, consequently, on the whole ADDING EMPHASIS IN WRITING Summary: This handout provides information on visual and textual devices for adding emphasis to your writing including textual formatting, punctuation, sentence structure, and the arrangement of words. Visual-Textual Devices for Achieving Emphasis In the days before computerized word processing and desktop publishing, the publishing process began with a manuscript and/or a typescript that was sent to a print shop where it would be prepared for publication and printed. In order to show emphasis, to highlight the title of a book, to refer to a word itself as a word, or to indicate a foreign word or phrase, the writer would use underlining in the typescript, which would signal the typesetter at the print shop to use italic font for those words. Even today, perhaps the simplest way to call attention to an otherwise unemphatic word or phrase is to underline or italicize it. Flaherty is the new committee chair, not Buckley. This mission is extremely important for our future: we must not fail! Because writers using computers today have access to a wide variety of fonts and textual effects, they are no longer limited to underlining to show emphasis. Still, especially for academic writing, italics or underlining is the preferred way to emphasize words or phrases when necessary. Writers usually choose one or the other method and use it consistently throughout an individual essay. In the final, published version of an article or book, italics are usually used. Writers in academic discourses and students learning to write academic papers are expected to express emphasis primarily through words themselves; overuse of various emphatic devices like changes of font face and size, boldface, all-capitals, and so on in the text of an essay creates the impression of a writer relying on flashy effects instead of clear and precise writing to make a point. Boldface is also used, especially outside of academia, to show emphasis as well as to highlight items in a list, as in the following examples. The picture that television commercials portray of the American home is far from realistic. The following three topics will be covered: 3 Topic 1: brief description of topic 1 Topic 2: brief description of topic 2 Topic 3: brief description of topic 3 Some writers use ALL-CAPITAL letters for emphasis, but they are usually unnecessary and can cause writing to appear cluttered and loud. In email correspondence, the use of all-caps throughout a message can create the unintended impression of shouting and is therefore discouraged. Visual-Textual Devices for Achieving Emphasis In the days before computerized word processing and desktop publishing, the publishing process began with a manuscript and/or a typescript that was sent to a print shop where it would be prepared for publication and printed. In order to show emphasis, to highlight the title of a book, to refer to a word itself as a word, or to indicate a foreign word or phrase, the writer would use underlining in the typescript, which would signal the typesetter at the print shop to use italic font for those words. Even today, perhaps the simplest way to call attention to an otherwise unemphatic word or phrase is to underline or italicize it. Flaherty is the new committee chair, not Buckley. This mission is extremely important for our future: we must not fail! Because writers using computers today have access to a wide variety of fonts and textual effects, they are no longer limited to underlining to show emphasis. Still, especially for academic writing, italics or underlining is the preferred way to emphasize words or phrases when necessary. Writers usually choose one or the other method and use it consistently throughout an individual essay. In the final, published version of an article or book, italics are usually used. Writers in academic discourses and students learning to write academic papers are expected to express emphasis primarily through words themselves; overuse of various emphatic devices like changes of font face and size, boldface, all-capitals, and so on in the text of an essay creates the impression of a writer relying on flashy effects instead of clear and precise writing to make a point. Boldface is also used, especially outside of academia, to show emphasis as well as to highlight items in a list, as in the following examples. The picture that television commercials portray of the American home is far from realistic. The following three topics will be covered: Topic 1: brief description of topic 1 Topic 2: brief description of topic 2 Topic 3: brief description of topic 3 Some writers use ALL-CAPITAL letters for emphasis, but they are usually unnecessary and can cause writing to appear cluttered and loud. In email correspondence, the use of all-caps throughout a message can create the unintended impression of shouting and is therefore discouraged. Choice and Arrangement of Words for Achieving Emphasis 4 The simplest way to emphasize something is to tell readers directly that what follows is important by using such words and phrases as especially, particularly, crucially, most importantly, and above all. Emphasis by repetition of key words can be especially effective in a series, as in the following example. See your good times come to color in minutes: pictures protected by an elegant finish, pictures you can take with an instant flash, pictures that can be made into beautiful enlargements. When a pattern is established through repetition and then broken, the varied part will be emphasized, as in the following example. Murtz Rent-a-car is first in reliability, first in service, and last in customer complaints. Besides disrupting an expectation set up by the context, you can also emphasize part of a sentence by departing from the basic structural patterns of the language. The inversion of the standard subject-verbobject pattern in the first sentence below into an object-subject-verb pattern in the second places emphasis on the out-of-sequence term, fifty dollars. I'd make fifty dollars in just two hours on a busy night at the restaurant. Fifty dollars I'd make in just two hours on a busy night at the restaurant. The initial and terminal positions of sentences are inherently more emphatic than the middle segment. Likewise, the main clause of a complex sentence receives more emphasis than subordinate clauses. Therefore, you should put words that you wish to emphasize near the beginnings and endings of sentences and should never bury important elements in subordinate clauses. Consider the following example. No one can deny that the computer has had a great effect upon the business world. Undeniably, the effect of the computer upon the business world has been great. In the first version of this sentence, "No one can deny" and "on the business world" are in the most emphasized positions. In addition, the writer has embedded the most important ideas in a subordinate clause: "that the computer has had a great effect." The edited version places the most important ideas in the main clause and in the initial and terminal slots of the sentence, creating a more engaging prose style. SENTENCE AND CLAUSE ARRANGEMENT FOR EMPHASIS Sentence Position and Variation for Achieving Emphasis An abrupt short sentence following a long sentence or a sequence of long sentences is often emphatic. For example, compare the following paragraphs. The second version emphasizes an important idea by placing it in an independent clause and placing it at the end of the paragraph: For a long time, but not any more, Japanese corporations used Southeast Asia merely as a cheap source of raw materials, as a place to dump outdated equipment and overstocked merchandise, and as a training ground for junior executives who needed minor league experience. For a long time Japanese corporations used Southeast Asia merely as a cheap source of raw materials, as a place to dump outdated equipment and overstocked merchandise, and as a training ground for junior executives who needed minor league experience. But those days have ended. 5 Varying a sentence by using a question after a series of statements is another way of achieving emphasis. The increased number of joggers, the booming sales of exercise bicycles and other physical training devices, the record number of entrants in marathon races—all clearly indicate the growing belief among Americans that strenuous, prolonged exercise is good for their health. But is it? Arrangement of Clauses for Achieving Emphasis Since the terminal position in the sentence carries the most weight and since the main clause is more emphatic than a subordinate clause in a complex sentence, writers often place the subordinate clause before the main clause to give maximal emphasis to the main clause. For example: I believe both of these applicants are superb even though it's hard to find good secretaries nowadays. Even though it's hard to find good secretaries nowadays, I believe both of these applicants are superb. CONCISENESS The goal of concise writing is to use the most effective words. Concise writing does not always have the fewest words, but it always uses the strongest ones. Writers often fill sentences with weak or unnecessary words that can be deleted or replaced. Words and phrases should be deliberately chosen for the work they are doing. Like bad employees, words that don't accomplish enough should be fired. When only the most effective words remain, writing will be far more concise and readable. This resource contains general conciseness tips followed by very specific strategies for pruning sentences. 1. Replace several vague words with more powerful and specific words. Often, writers use several small and ambiguous words to express a concept, wasting energy expressing ideas better relayed through fewer specific words. As a general rule, more specific words lead to more concise writing. Because of the variety of nouns, verbs, and adjectives, most things have a closely corresponding description. Brainstorming or searching a thesaurus can lead to the word best suited for a specific instance. Notice that the examples below actually convey more as they drop in word count. Wordy: The politician talked about several of the merits of after-school programs in his speech (14 words) Concise: The politician touted after-school programs in his speech. (8 words) Wordy: Suzie believed but could not confirm that Billy had feelings of affection for her. (14 words) Concise: Suzie assumed that Billy adored her. (6 words) Wordy: Our website has made available many of the things you can use for making a decision on the best dentist. (20 words) Concise: Our website presents criteria for determining the best dentist. (9 words) Wordy: Working as a pupil under a someone who develops photos was an experience that really helped me learn a lot. (20 words) Concise: Working as a photo technician's apprentice was an educational experience. (10 words) 6 2. Interrogate every word in a sentence Check every word to make sure that it is providing something important and unique to a sentence. If words are dead weight, they can be deleted or replaced. Other sections in this handout cover this concept more specifically, but there are some general examples below containing sentences with words that could be cut. Wordy: The teacher demonstrated some of the various ways and methods for cutting words from my essay that I had written for class. (22 words) Concise: The teacher demonstrated methods for cutting words from my essay. (10 words) Wordy: Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood formed a new band of musicians together in 1969, giving it the ironic name of Blind Faith because early speculation that was spreading everywhere about the band suggested that the new musical group would be good enough to rival the earlier bands that both men had been in, Cream and Traffic, which people had really liked and had been very popular. (66 words) Concise: Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood formed a new band in 1969, ironically naming it Blind Faith because speculation suggested that the group would rival the musicians’ previous popular bands, Cream and Traffic. (32 words) Wordy: Many have made the wise observation that when a stone is in motion rolling down a hill or incline that that moving stone is not as likely to be covered all over with the kind of thick green moss that grows on stationary unmoving things and becomes a nuisance and suggests that those things haven’t moved in a long time and probably won’t move any time soon. (67 words) Concise: A rolling stone gathers no moss. (6 words) 3. Combine Sentences. Some information does not require a full sentence, and can easily be inserted into another sentence without losing any of its value. To get more strategies for sentence combining, see the handout on Sentence Variety. Wordy: Ludwig's castles are an astounding marriage of beauty and madness. By his death, he had commissioned three castles. (18 words) Concise: Ludwig's three castles are an astounding marriage of beauty and madness. (11 words) Wordy: The supposed crash of a UFO in Roswell, New Mexico aroused interest in extraterrestrial life. This crash is rumored to have occurred in 1947. (24 words) Concise: The supposed 1947 crash of a UFO in Roswell, New Mexico aroused interest in extraterrestrial life. (16 words). Eliminating Words 1. Eliminate words that explain the obvious or provide excessive detail 7 Always consider readers while drafting and revising writing. If passages explain or describe details that would already be obvious to readers, delete or reword them. Readers are also very adept at filling in the non-essential aspects of a narrative, as in the fourth example. Wordy: I received your inquiry that you wrote about tennis rackets yesterday, and read it thoroughly. Yes, we do have... (19 words) Concise: I received your inquiry about tennis rackets yesterday. Yes, we do have...(12 words) Wordy: It goes without saying that we are acquainted with your policy on filing tax returns, and we have every intention of complying with the regulations that you have mentioned. (29 words) Concise: We intend to comply with the tax-return regulations that you have mentioned. (12 words) Wordy: Imagine a mental picture of someone engaged in the intellectual activity of trying to learn what the rules are for how to play the game of chess. (27 words) Concise: Imagine someone trying to learn the rules of chess. (9 words) Wordy: After booking a ticket to Dallas from a travel agent, I packed my bags and arranged for a taxi to the airport. Once there, I checked in, went through security, and was ready to board. But problems beyond my control led to a three-hour delay before takeoff. (47 words) Concise: My flight to Dallas was delayed for three hours. (9 words) Wordy: Baseball, one of our oldest and most popular outdoor summer sports in terms of total attendance at ball parks and viewing on television, has the kind of rhythm of play on the field that alternates between times when players passively wait with no action taking place between the pitches to the batter and then times when they explode into action as the batter hits a pitched ball to one of the players and the player fields it. (77 words) Concise: Baseball has a rhythm that alternates between waiting and explosive action. (11 words) 2. Eliminate unnecessary determiners and modifiers Writers sometimes clog up their prose with one or more extra words or phrases that seem to determine narrowly or to modify the meaning of a noun but don't actually add to the meaning of the sentence. Although such words and phrases can be meaningful in the appropriate context, they are often used as "filler" and can easily be eliminated. Wordy: Any particular type of dessert is fine with me. (9 words) Concise: Any dessert is fine with me. (6 words) Wordy: Balancing the budget by Friday is an impossibility without some kind of extra help. (14 words) Concise: Balancing the budget by Friday is impossible without extra help. (10 words) Wordy: For all intents and purposes, American industrial productivity generally depends on certain factors that are really more psychological in kind than of any given technological aspect. (26 words) 8 Concise: American industrial productivity depends more on psychological than on technological factors. (11 words) Here's a list of some words and phrases that can often be pruned away to make sentences clearer: o o o o o o o o o o o o kind of sort of type of really basically for all intents and purposes definitely actually generally individual specific particular 3. Omit repetitive wording Watch for phrases or longer passages which repeat words with similar meanings. Words that don't build on the content of sentences or paragraphs are rarely necessary. Wordy: I would appreciate it if you would bring to the attention of your drafting officers the administrator's dislike of long sentences and paragraphs in messages to the field and in other items drafted for her signature or approval, as well as in all correspondence, reports, and studies. Please encourage your section to keep their sentences short. (56 words) Concise: Please encourage your drafting officers to keep sentences and paragraphs in letters, reports, and studies short. Dr. Lomas, the administrator, has mentioned that reports and memos drafted for her approval recently have been wordy and thus time-consuming. (37 words) Wordy: The supply manager considered the correcting typewriter an unneeded luxury. (10 words) Concise: The supply manager considered the correcting typewriter a luxury. (9 words) Wordy: Our branch office currently employs five tellers. These tellers do an excellent job Monday through Thursday but cannot keep up with the rush on Friday and Saturday. (27 words) Concise: Our branch office currently employs five tellers, who do an excellent job Monday through Thursday but cannot keep up with Friday and Saturday rush periods. (25 words) 4. Omit Redundant Pairs Many pairs of words imply each other. Finish implies complete, so the phrase completely finish is redundant in most cases. So are many other pairs of words: o past memories 9 o o o o o o o o o o o o o various differences each individual _______ basic fundamentals true facts important essentials future plans terrible tragedy end result final outcome free gift past history unexpected surprise sudden crisis A related expression that's not redundant as much as it is illogical is "very unique." Since unique means "one of a kind," adding modifiers of degree such as "very," "so," "especially," "somewhat," "extremely," and so on is illogical. One-of-a-kind-ness has no gradations; something is either unique or it is not. Wordy: Before the travel agent was completely able to finish explaining the various differences among all of the many very unique vacation packages his travel agency was offering, the customer changed her future plans. (33 words) Concise: Before the travel agent finished explaining the differences among the unique vacation packages his travel agency was offering, the customer changed her plans. (23 words) 5. Omit Redundant Categories Specific words imply their general categories, so we usually don't have to state both. We know that a period is a segment of time, that pink is a color, that shiny is an appearance. In each of the following phrases, the general category term can be dropped, leaving just the specific descriptive word: o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o large in size often times of a bright color heavy in weight period in time round in shape at an early time economics field of cheap quality honest in character of an uncertain condition in a confused state unusual in nature extreme in degree of a strange type 10 Wordy: During that time period, many car buyers preferred cars that were pink in color and shiny in appearance. (18 words) Concise: During that period, many car buyers preferred pink, shiny cars. (10 words) Wordy: The microscope revealed a group of organisms that were round in shape and peculiar in nature. (16 words) Concise: The microscope revealed a group of peculiar, round organisms. (9 words) Changing Phrases 1. Change phrases into single-words and adjectives Using phrases to convey meaning that could be presented in a single word contributes to wordiness. Convert phrases into single words when possible. Wordy: The employee with ambition... (4 words) Concise: The ambitious employee... (3 words) Wordy: The department showing the best performance... (6 words) Concise: The best-performing department... (4 words) Wordy: Jeff Converse, our chief of consulting, suggested at our last board meeting the installation of microfilm equipment in the department of data processing. (23 words) Concise: At our last board meeting, Chief Consultant Jeff Converse suggested that we install microfilm equipment in the data processing department. (20 words) Wordy: We read the letter we received yesterday and reviewed it thoroughly. Concise: We thorougly read the letter we received yesterday. Wordy: As you carefully read what you have written to improve your wording and catch small errors of spelling, punctuation, and so on, the thing to do before you do anything else is to try to see where a series of words expressing action could replace the ideas found in nouns rather than verbs. (53 words) Concise: As you edit, first find nominalizations that you can replace with verb phrases. (13 words) 2. Change unnecessary that, who, and which clauses into phrases Using a clause to convey meaning that could be presented in a phrase or even a word contributes to wordiness. Convert modifying clauses into phrases or single words when possible. Wordy: The report, which was released recently... (6 words) Concise: The recently released report... (4 words) Wordy: All applicants who are interested in the job must... (9 words) 11 Concise: All job applicants must... (4 words) Wordy: The system that is most efficient and accurate... (8 words) Concise: The most efficient and accurate system... (6 words)' 3. Change Passive Verbs into Active Verbs See our document on active and passive voice for a more thorough explanation of this topic. Wordy: An account was opened by Mrs. Simms. (7 words) Concise: Mrs. Simms opened an account. (5 words) Wordy: Your figures were checked by the research department. (8 words) Concise: The research department checked your figures. (6 words) Things to Avoid 1. Avoid overusing expletives at the beginning of sentences Expletives are phrases of the form it + be-verb or there + be-verb. Such expressions can be rhetorically effective for emphasis in some situations, but overuse or unnecessary use of expletive constructions creates wordy prose. Take the following example: "It is imperative that we find a solution." The same meaning could be expressed with this more succinct wording: "We must find a solution." But using the expletive construction allows the writer to emphasize the urgency of the situation by placing the word imperative near the beginning of the sentence, so the version with the expletive may be preferable. Still, you should generally avoid excessive or unnecessary use of expletives. The most common kind of unnecessary expletive construction involves an expletive followed by a noun and a relative clause beginning with that, which, or who. In most cases, concise sentences can be created by eliminating the expletive opening, making the noun the subject of the sentence, and eliminating the relative pronoun. Wordy: It is the governor who signs or vetoes bills. (9 words) Concise: The governor signs or vetoes bills. (6 words) Wordy: There are four rules that should be observed: ... (8 words) Concise: Four rules should be observed:... (5 words) Wordy: There was a big explosion, which shook the windows, and people ran into the street. (15 words) Concise: A big explosion shook the windows, and people ran into the street. (12 words) 2. Avoid overusing noun forms of verbs Use verbs when possible rather than noun forms known as nominalizations. Sentences with many nominalizations usually have forms of be as the main verbs. Using the action verbs disguised in nominalizations as the main verbs--instead of forms of be--can help to create engaging rather than dull prose. 12 Wordy: The function of this department is the collection of accounts. (10 words) Concise: This department collects accounts. (4 words) Wordy: The current focus of the medical profession is disease prevention. (10 words) Concise: The medical profession currently focuses on disease prevention. (8 words) 3. Avoid unnecessary infinitive phrases Some infinitive phrases can be converted into finite verbs or brief noun phrases. Making such changes also often results in the replacement of a be-verb with an action verb. Wordy: The duty of a clerk is to check all incoming mail and to record it. (15 words) Concise: A clerk checks and records all incoming mail. (8 words) Wordy: A shortage of tellers at our branch office on Friday and Saturday during rush hours has caused customers to become dissatisfied with service. (23 words) Concise: A teller shortage at our branch office on Friday and Saturday during rush hours has caused customer dissatisfaction. (18 words) 4. Avoid circumlocutions in favor of direct expressions Circumlocutions are commonly used roundabout expressions that take several words to say what could be said more succinctly. We often overlook them because many such expressions are habitual figures of speech. In writing, though, they should be avoided since they add extra words without extra meaning. Of course, occasionally you may for rhetorical effect decide to use, say, an expletive construction instead of a more succinct expression. These guidelines should be taken as general recommendations, not absolute rules. Wordy: At this/that point in time... (2/4 words) Concise: Now/then... (1 word) Wordy: In accordance with your request... (5 words) Concise: As you requested... (3 words) Below are some other words which may simplify lengthier circumlocutions. "Because," "Since," "Why" = o o o o o o o the reason for for the reason that owing/due to the fact that in light of the fact that considering the fact that on the grounds that this is why "When" = 13 o o o on the occasion of in a situation in which under circumstances in which "about" = o o o o o as regards in reference to with regard to concerning the matter of where ________ is concerned "Must," "Should" = o o o o o it is crucial that it is necessary that there is a need/necessity for it is important that cannot be avoided "Can" = o o o o is able to has the opportunity to has the capacity for has the ability to "May," "Might," "Could" = o o o o it is possible that there is a chance that it could happen that the possibility exists for Wordy: It is possible that nothing will come of these preparations. (10 words) Concise: Nothing may come of these preparations. (6 words) Wordy: She has the ability to influence the outcome. (8 words) Concise: She can influence the outcome. (5 words) Wordy: It is necessary that we take a stand on this pressing issue. (12 words) Concise: We must take a stand on this pressing issue. (9 words) Sentence Variety Strategies for Variation 14 Adding sentence variety to prose can give it life and rhythm. Too many sentences with the same structure and length can grow monotonous for readers. Varying sentence style and structure can also reduce repetition and add emphasis. Long sentences work well for incorporating a lot of information, and short sentences can often maximize crucial points. These general tips may help add variety to similar sentences. 1. Vary the rhythm by alternating short and long sentences. Several sentences of the same length can make for bland writing. To enliven paragraphs, write sentences of different lengths. This will also allow for effective emphasis. Example: The Winslow family visited Canada and Alaska last summer to find some native American art. In Anchorage stores they found some excellent examples of soapstone carvings. But they couldn't find a dealer selling any of the woven wall hangings they wanted. They were very disappointed when they left Anchorage empty-handed. Revision: The Winslow family visited Canada and Alaska last summer to find some native American art, such as soapstone carvings and wall hangings. Anchorage stores had many soapstone items available. Still, they were disappointed to learn that wall hangings, which they had especially wanted, were difficult to find. Sadly, they left empty-handed. Example: Many really good blues guitarists have all had the last name King. They have been named Freddie King and Albert King and B.B. King. The name King must make a bluesman a really good bluesman. The bluesmen named King have all been very talented and good guitar players. The claim that a name can make a guitarist good may not be that far fetched. Revision: What makes a good bluesman? Maybe, just maybe, it's all in a stately name. B.B. King. Freddie King. Albert King. It's no coincidence that they're the royalty of their genre. When their fingers dance like court jesters, their guitars gleam like scepters, and their voices bellow like regal trumpets, they seem almost like nobility. Hearing their music is like walking into the throne room. They really are kings. 2. Vary sentence openings. If too many sentences start with the same word, especially "The," "It," "This," or "I," prose can grow tedious for readers, so changing opening words and phrases can be refreshing. Below are alternative openings for a fairly standard sentence. Notice that different beginnings can alter not only the structure but also the emphasis of the sentence. They may also require rephrasing in sentences before or after this one, meaning that one change could lead to an abundance of sentence variety. Example: The biggest coincidence that day happened when David and I ended up sitting next to each other at the Super Bowl. Possible Revisions: Coincidentally, David and I ended up sitting right next to each other at the Super Bowl. In an amazing coincidence, David and I ended up sitting next to each other at the Super Bowl. Sitting next to David at the Super Bowl was a tremendous coincidence. But the biggest coincidence that day happened when David and I ended up sitting next to each other at the Super Bowl. When I sat down at the Super Bowl, I realized that, by sheer coincidence, I was directly next to David. By sheer coincidence, I ended up sitting directly next to David at the Super Bowl. 15 With over 50,000 fans at the Super Bowl, it took an incredible coincidence for me to end up sitting right next to David. What are the odds that I would have ended up sitting right next to David at the Super Bowl? David and I, without any prior planning, ended up sitting right next to each other at the Super Bowl. Without any prior planning, David and I ended up sitting right next to each other at the Super Bowl. At the crowded Super Bowl, packed with 50,000 screaming fans, David and I ended up sitting right next to each other by sheer coincidence. Though I hadn't made any advance arrangements with David, we ended up sitting right next to each other at the Super Bowl. Many amazing coincidences occurred that day, but nothing topped sitting right next to David at the Super Bowl. Unbelievable, I know, but David and I ended up sitting right next to each other at the Super Bowl. Guided by some bizarre coincidence, David and I ended up sitting right next to each other at the Super Bowl. SENTENCE TYPES Structurally, English sentences can be classified four different ways, though there are endless constructions of each. The classifications are based on the number of independent and dependent clauses a sentence contains. An independent clause forms a complete sentence on its own, while a dependent clause needs another clause to make a complete sentence. By learning these types, writers can add complexity and variation to their sentences. 1. Simple sentence: A sentence with one independent clause and no dependent clauses. My aunt enjoyed taking the hayride with you. China's Han Dynasty marked an official recognition of Confucianism. 2. Compound Sentence: A sentence with multiple independent clauses but no dependent clauses. The clown frightened the little girl, and she ran off screaming. The Freedom Riders departed on May 4, 1961, and they were determined to travel through many southern states. 3. Complex Sentence: A sentence with one independent clause and at least one dependent clause. After Mary added up all the sales, she discovered that the lemonade stand was 32 cents short While all of his paintings are fascinating, Hieronymus Bosch's triptychs, full of mayhem and madness, are the real highlight of his art. 4. Complex-Compound Sentence: A sentence with multiple independent clauses and at least one dependent clause. 16 With her reputation on the line, Peggy played against a fierce opponent at the Scrabble competition, and overcoming nerve-racking competition, she won the game with one wellplaced word. Catch-22 is widely regarded as Joseph Heller's best novel, and because Heller served in World War II, which the novel satirizes, the zany but savage wit of the novel packs an extra punch. For Short, Choppy Sentences If your writing contains lots of short sentences that give it a choppy rhythm, consider these tips. 1. Combine Sentences With Conjunctions: Join complete sentences, clauses, and phrases with conjunctions: and, but, or, nor, yet, for, so Example: Doonesbury cartoons satirize contemporary politics. Readers don't always find this funny. They demand that newspapers not carry the strip. Revision: Doonesbury cartoons laugh at contemporary politicians, but readers don't always find this funny and demand that newspapers not carry the strip. 2. Link Sentences Through Subordination: Link two related sentences to each other so that one carries the main idea and the other is no longer a complete sentence (subordination). Use connectors such as the ones listed below to show the relationship. after, although, as, as if, because, before, even if, even though, if, if only, rather than, since, that, though, unless, until, when, where, whereas, wherever, whether, which, while Example: The campus parking problem is getting worse. The university is not building any new garages. Revision: The campus parking problem is getting worse because the university is not building any new garages. Example: The US has been highly dependent on foreign oil for many years. Alternate sources of energy are only now being sought. Revision: Although the US has been highly dependent on foreign oil for many years, alternate sources are only now being sought. Notice in these examples that the location of the clause beginning with the dependent marker (the connector word) is flexible. This flexibility can be useful in creating varied rhythmic patterns over the course of a paragraph. For Repeated Subjects or Topics Handling the same topic for several sentences can lead to repetitive sentences. When that happens, consider using these parts of speech to fix the problem. 1. Relative pronouns 17 Embed one sentence inside the other using a clause starting with one of the relative pronouns listed below. which, who, whoever, whom, that, whose Example: Indiana used to be mainly an agricultural state. It has recently attracted more industry. Revision: Indiana, which used to be mainly an agricultural state, has recently attracted more industry. Example: One of the cameras was not packed very well. It was damaged during the move. Revision: The camera that was not packed very well was damaged during the move. Example: The experiment failed because of Murphy's Law. This law states that if something can go wrong, it will. Revision: The experiment failed because of Murphy's Law, which states that if something can go wrong, it will. Example: Doctor Ramirez specializes in sports medicine. She helped my cousin recover from a basketball injury. Revision 1: Doctor Ramirez, who specializes in sports medicine, helped my cousin recover from a basketball injury. Revision 2: Doctor Ramirez, whose specialty is sports medicine, helped my cousin recover from a basketball injury. 2. Participles Eliminate a be verb (am, is, was, were, are) and substitute a participle: Present participles end in -ing, for example: speaking, carrying, wearing, dreaming. Past participles usually end in -ed, -en, -d, -n, or -t but can be irregular, for example: worried, eaten, saved, seen, dealt, taught. Example: Wei Xie was surprised to get a phone call from his sister. He was happy to hear her voice again. Revision 1: Wei Xie, surprised to get a phone call from his sister, was happy to hear her voice again. Revision 2: Surprised to get a phone call from his sister, Wei Xie was happy to hear her voice again. 3. Prepositions Turn a sentence into a prepositional phrase using one of the words below: 18 about, above, across, after, against, along, among, around, as, behind, below, beneath, beside, between, by, despite, down, during, except, for, from, in, inside, near, next to, of, off, on, out, over, past, to, under, until, up, with Example: The university has been facing pressure to cut its budget. It has eliminated funding for important programs. (two independent clauses) Revision: Under pressure to cut its budget, the university has eliminated funding for important programs. (prepositional phrase, independent clause) Example: Billy snuck a cookie from the desert table. This was against his mother's wishes. Revision: Against his mother's wishes, Billy snuck a cookie from the desert table. For Similar Sentence Patterns or Rhythms When several sentences have similar patterns or rhythms, try using the following kinds of words to shake up the writing. 1. Dependent markers Put clauses and phrases with the listed dependent markers at the beginning of some sentences instead of starting each sentence with the subject: after, although, as, as if, because, before, even if, even though, if, in order to, since, though, unless, until, whatever, when, whenever, whether, and while Example: The room fell silent when the TV newscaster reported the story of the earthquake. Revision: When the TV newscaster reported the story of the earthquake, the room fell silent. Example: Thieves made off with Edvard Munch's The Scream before police could stop them. Revision: Before police could stop them, thieves made off with Edvard Munch's The Scream. 2. Transitional words and phrases Vary the rhythm by adding transitional words at the beginning of some sentences: accordingly, after all, afterward, also, although, and, but, consequently, despite, earlier, even though, for example, for instance, however, in conclusion, in contrast, in fact, in the meantime, in the same way, indeed, just as... so, meanwhile, moreover, nevertheless, not only... but also, now, on the contrary, on the other hand, on the whole, otherwise, regardless, shortly, similarly, specifically, still, that is, then, therefore, though, thus, yet Example: Fast food corporations are producing and advertising bigger items and high-fat combination meals. The American population faces a growing epidemic of obesity. Revision: Fast food corporations are producing and advertising bigger items and high-fat combination meals. Meanwhile, the American population faces a growing epidemic of obesity. 19 PARALLEL STRUCTURE IN PROFESSIONAL WRITING It is important to be consistent in your wording in professional writing, particularly in employment documents; this is called parallelism. When you are expressing ideas of equal weight in your writing, parallel sentence structures can echo that fact and offer you a writing style that uses balance and rhythm to help deliver your meaning. You can use parallel structure in any kind of writing that you do, whether that writing is on or off the job. Here are some examples that demonstrate how to implement parallelism in preparing employment documents. When you're done reviewing them, try the practice exercise at the bottom. Incorrect: My degree, my work experience, and ability to complete complicated projects qualify me for the job. Correct: My degree, my work experience, and my ability to complete complicated projects qualify me for the job. Incorrect: Prepared weekly field payroll Material purchasing, expediting, and returning Recording OSHA regulated documentation Change orders Maintained hard copies of field documentation Correct: Prepared weekly field payroll Handled material purchasing, expediting, and returning Recorded OSHA regulated documentation Processed change orders Maintained hard copies of field documentation Practice Correct the following bulleted list from a final report. On the web page there is much wasted space which is unappealing to the viewer. Following are suggestions for eliminating the unwanted blank space: Move some of the text into the blank space Centering the picture Centering the picture and add text to each side On the right of the picture, tell a little bit about the picture (who owns the balloon, what year and where this picture was taken, etc.) Have pictures that stretch the length of the screen, like with a panoramic camera Or as a last resort even take the picture out 20 QUOTING, PARAPHRASING, AND SUMMARIZING This handout is intended to help you become more comfortable with the uses of and distinctions among quotations, paraphrases, and summaries. This handout compares and contrasts the three terms, gives some pointers, and includes a short excerpt that you can use to practice these skills. What are the differences among quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing? These three ways of incorporating other writers' work into your own writing differ according to the closeness of your writing to the source writing. Quotations must be identical to the original, using a narrow segment of the source. They must match the source document word for word and must be attributed to the original author. Paraphrasing involves putting a passage from source material into your own words. A paraphrase must also be attributed to the original source. Paraphrased material is usually shorter than the original passage, taking a somewhat broader segment of the source and condensing it slightly. Summarizing involves putting the main idea(s) into your own words, including only the main point(s). Once again, it is necessary to attribute summarized ideas to the original source. Summaries are significantly shorter than the original and take a broad overview of the source material. Why use quotations, paraphrases, and summaries? Quotations, paraphrases, and summaries serve many purposes. You might use them to . . . Provide support for claims or add credibility to your writing Refer to work that leads up to the work you are now doing Give examples of several points of view on a subject Call attention to a position that you wish to agree or disagree with Highlight a particularly striking phrase, sentence, or passage by quoting the original Distance yourself from the original by quoting it in order to cue readers that the words are not your own Expand the breadth or depth of your writing Writers frequently intertwine summaries, paraphrases, and quotations. As part of a summary of an article, a chapter, or a book, a writer might include paraphrases of various key points blended with quotations of striking or suggestive phrases as in the following example: In his famous and influential work On the Interpretation of Dreams, Sigmund Freud argues that dreams are the "royal road to the unconscious" (page #), expressing in coded imagery the dreamer's unfulfilled wishes through a process known as the "dream work" (page #). According to Freud, actual but unacceptable desires are censored internally and subjected to coding through layers of condensation and displacement before emerging in a kind of rebus puzzle in the dream itself (page #s). How to use quotations, paraphrases, and summaries 21 Practice summarizing the following essay, using paraphrases and quotations as you go. It might be helpful to follow these steps: Read the entire text, noting the key points and main ideas. Summarize in your own words what the single main idea of the essay is. Paraphrase important supporting points that come up in the essay. Consider any words, phrases, or brief passages that you believe should be quoted directly. There are several ways to integrate quotations into your text. Often, a short quotation works well when integrated into a sentence. Longer quotations can stand alone. Remember that quoting should be done only sparingly; be sure that you have a good reason to include a direct quotation when you decide to do so. You'll find guidelines for citing sources and punctuating citations at our documentation guide pages. Sample essay for Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Quoting The following is a sample essay you can practice quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing. Examples of each task are provided at the end of the essay for further reference. So That Nobody Has To Go To School If They Don't Want To by Roger Sipher A decline in standardized test scores is but the most recent indicator that American education is in trouble. One reason for the crisis is that present mandatory-attendance laws force many to attend school who have no wish to be there. Such children have little desire to learn and are so antagonistic to school that neither they nor more highly motivated students receive the quality education that is the birthright of every American. The solution to this problem is simple: Abolish compulsory-attendance laws and allow only those who are committed to getting an education to attend. This will not end public education. Contrary to conventional belief, legislators enacted compulsoryattendance laws to legalize what already existed. William Landes and Lewis Solomon, economists, found little evidence that mandatory-attendance laws increased the number of children in school. They found, too, that school systems have never effectively enforced such laws, usually because of the expense involved. There is no contradiction between the assertion that compulsory attendance has had little effect on the number of children attending school and the argument that repeal would be a positive step toward improving education. Most parents want a high school education for their children. Unfortunately, compulsory attendance hampers the ability of public school officials to enforce legitimate educational and disciplinary policies and thereby make the education a good one. Private schools have no such problem. They can fail or dismiss students, knowing such students can attend public school. Without compulsory attendance, public schools would be freer to oust students whose academic or personal behavior undermines the educational mission of the institution. 22 Has not the noble experiment of a formal education for everyone failed? While we pay homage to the homily, "You can lead a horse to water but you can't make him drink," we have pretended it is not true in education. Ask high school teachers if recalcitrant students learn anything of value. Ask teachers if these students do any homework. Quite the contrary, these students know they will be passed from grade to grade until they are old enough to quit or until, as is more likely, they receive a high school diploma. At the point when students could legally quit, most choose to remain since they know they are likely to be allowed to graduate whether they do acceptable work or not. Abolition of archaic attendance laws would produce enormous dividends. First, it would alert everyone that school is a serious place where one goes to learn. Schools are neither day-care centers nor indoor street corners. Young people who resist learning should stay away; indeed, an end to compulsory schooling would require them to stay away. Second, students opposed to learning would not be able to pollute the educational atmosphere for those who want to learn. Teachers could stop policing recalcitrant students and start educating. Third, grades would show what they are supposed to: how well a student is learning. Parents could again read report cards and know if their children were making progress. Fourth, public esteem for schools would increase. People would stop regarding them as way stations for adolescents and start thinking of them as institutions for educating America's youth. Fifth, elementary schools would change because students would find out early they had better learn something or risk flunking out later. Elementary teachers would no longer have to pass their failures on to junior high and high school. Sixth, the cost of enforcing compulsory education would be eliminated. Despite enforcement efforts, nearly 15 percent of the school-age children in our largest cities are almost permanently absent from school. Communities could use these savings to support institutions to deal with young people not in school. If, in the long run, these institutions prove more costly, at least we would not confuse their mission with that of schools. Schools should be for education. At present, they are only tangentially so. They have attempted to serve an all-encompassing social function, trying to be all things to all people. In the process they have failed miserably at what they were originally formed to accomplish. Example Summary, Paraphrase, and Quotation from the Essay: Example summary: Roger Sipher makes his case for getting rid of compulsory-attendance laws in primary and secondary schools with six arguments. These fall into three groups—first that education is for those who want to learn and by including those that don't want to learn, everyone suffers. Second, that grades would be reflective of effort and elementary school teachers wouldn't feel compelled to pass 23 failing students. Third, that schools would both save money and save face with the elimination of compulsory-attendance laws. Example paraphrase: Roger Sipher concludes his essay by insisting that schools have failed to fulfill their primary duty of education because they try to fill multiple social functions. Example quotation: According to Roger Sipher, a solution to the perceived crisis of American education is to "Abolish compulsory-attendance laws and allow only those who are committed to getting an education to attend" (Page#). (Source: The Online Writing Lab (OWL) at Purdue University: http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/681/01/) 24