Understanding current electricity

advertisement

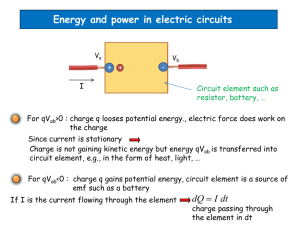

JSSS Teacher support material Understanding current electricity OP49-OP60 Introduction Recent research into students’ understanding of current electricity confirms the classroom experience of science teachers that it is a topic where misconceptions are plentiful. Sometimes there is only partial understanding but often there are incorrect ideas. Students will know from experience that electrical and electronic gadgets must be switched on, can work from batteries or from being plugged in, can give electric shocks in some circumstances and so on. Through these experiences, and also possibly from work at primary school, students will have developed some simple ideas about how electrical appliances work. Some of these ideas may be on the wrong track but many will also be on the right lines. Typical ideas along the right lines include: the need for a complete circuit the circuit cannot have gaps energy comes from the battery the electric current flows the battery runs out of energy Typical ideas on the wrong track include: electricity flows from both ends of the battery electricity is used up the battery runs out of electric current shorter connecting wires need less electricity current flows only as far as the bulb from one side of the battery The key challenge is to lead students from these basic ideas to some understanding of how electric circuits work in terms of objects and ideas that they cannot see or directly experience. Students should eventually be able to explain and visualise the working of electric circuits in terms of charged particles, current, energy and resistance, i.e., to understand what is happening in terms of the ELECTRIC CIRCUIT MODEL. To advance students’ understanding along the right lines, the teaching approach might involve the following elements, in sequence: (1) Using PROBES to establish the students’ initial level of understanding and to build on any ideas along the right lines and redirect ideas that are on the wrong track. (2) Building a single loop BIG CIRCUIT with the students in a ring holding the different components. Through investigation and group discussion, the basic requirements of continuity through the conductors from battery to bulb and questions about what is happening in various parts of the circuit can be teased out. -1- JSSS Teacher support material (3) Developing the ELECTRIC CIRCUIT MODEL either directly through discussion/ computer graphics or indirectly through the use of the SUPERMARKET PICTURE and LOOP OF ROPE analogies. (4) Reinforcing the electric circuit model through an INVESTIGATIVE APPROACH with the students working in groups. The investigative approach will involve: making predictions building suitable circuits from simple components testing to see what actually happens recording the conclusions in worksheets As a bonus, students will also be learning how to represent circuits using standard circuit diagram symbols. Students will also develop practical know-how by constructing and trouble-shooting simple electric circuits. (5) Using further PROBES to establish how successful the various activities have been in developing students’ understanding of the correct electric circuit model. Information from the checking of these sheets can then be used to incorporate remedial action into future teaching strategies. The Big Circuit The Big Circuit helps to open up the problem of coming to understand how an electric circuit works to focus attention on the need for some transport mechanism to transfer energy from the battery to the bulb to lay the groundwork towards developing a scientific model to explain how an electric circuit works Probing aspects of the Big Circuit Build the big circuit, leaving one final connection to the battery unmade. Before making this final connection, each person should be given the option of holding their link in the circuit by the leads or by the attached crocodile clips. 1. What do you think will happen when the final battery connection is made? 2. How fast did the bulb light? 3. Is there anything else happening to the bulb? Touch the bulb quickly and report back. 4. Predict what you think will happen if the bulb is moved to a different position in the circuit. 5. Will the bulb light if it is connected to the left-hand side of the battery? 6. Will the bulb light if it is connected to the right-hand side of the battery? 7. Suggest a number of ways to prevent the bulb from lighting. -2- JSSS Teacher support material Building the Big circuit 12 V battery, 12 V bulb, set of different materials and some connecting leads with crocodile clips Probe and tease out student’s existing ideas on: circuit continuity how fast the bulb lights despite its distance from the battery conductors and insulators switches Note: All analogies have their strengths and weaknesses. The SUPERMARKET PICTURE used below can be used for gaining insight into the charged particles /energy aspect of the ELECTRIC CIRCUIT MODEL. The ‘LOOP OF ROPE’ PICTURE used below offers an insight into the current/resistance aspect of the ELECTRIC CIRCUIT MODEL. -3- JSSS Teacher support material The Supermarket Picture DEVELOPING THE ANALOGY The battery is a source of energy Just as the bakery is the source of the bread. The energy is carried around the circuit by electrically charged particles Just as the bread is carried around by the vans. The electrically charged particles are part of the atoms already there in the wire Just as the waiting delivery vans. The energy carried by the charged particles is converted into other forms in the bulb filament Just as the bread is delivered to the supermarket by the vans. The bread-van analogy is useful for students to get some understanding that the battery is a source of energy and that there has to be a mechanism whereby the energy can be converted into heat and light in the bulb. They must accept that there is a continuous loop of vans. -4- JSSS Teacher support material The ‘Loop Of Rope’ Picture The battery is represented by the teacher/student moving the rope The bulb filament is represented by the student gripping the rope The electric current is represented by the moving rope DEVELOPING THE ANALOGY Developing The Analogy Charged particles originate in the circuit The rope isn’t coming from the teacher/student moving the rope – he/she is just making it move around. In just the same way the charged particles don’t come from the battery. The battery just makes them move around the circuit. Charged particles all round the circuit are set in motion together As soon as the teacher/student sets the rope in motion it starts moving at each point in the loop. In just the same way, as soon as the circuit is completed, the charged particles start moving in all parts of the circuit. Current is conserved The same amount of rope returns to the teacher/student as leaves him/her. In just the same way the current does not get used up on the way round the circuit. Energy is transferred where there is resistance The student gripping the rope can feel his/her hands warming up because he/she is gripping the rope. There is heating due to the resistance as the rope passes through his/her fingers. In just the same way, the energy of the charged particles is converted into heat in the filament because it offers increased resistance to the moving particles. Adding another battery doubles the available energy Adding a second battery is just like the teacher/student pulling and pushing on the rope with twice the effort. The rope moves around more quickly which is just like having an increased current. -5- JSSS Teacher support material Electric current When a battery is connected up to a lamp to make a complete circuit, there is an electric current everywhere in the circuit. The electric current arises from the movement of negatively charged particles, electrons, around the circuit. The electrons originate in the circuit itself. They are simply part of the atoms that make up the battery, wires and bulb. When these components are not connected into a circuit, the free electrons move around a lattice of vibrating positive ions but do not undergo any net displacement. (Students should be familiar with negative and positive charges and their behaviour from static electricity). When all the components are connected up to form a circuit, the negatively charged electrons in the circuit are attracted to the positive terminals in the battery. The electrons drift toward the positive terminal of the battery. How do you explain that it is the electrons moving around the circuit which enables the transfer of energy from battery to bulb? The following explanation goes beyond Junior Certificate Physics, but may be useful background so that students do not get the wrong ideas about current and charge. When a simple circuit is complete, the negatively charged electrons throughout the circuit are pushed away from the negative terminal of the battery and attracted toward the positive terminal. The battery creates an electric field around the circuit and the electrons move due to the effect of this field around the circuit. Think of the way mass behaves near to the earth! Mass feels the pull of the earth and falls toward it. Likewise, electrons are attracted to the positive terminal of the battery and move towards it. All of the electrons experience the effect of the battery even if they are not in direct contact with either of the battery terminals, just as mass feels the effect of the earth even when it is some distance away from it. As the electrons move in the circuit, they collide with the ions in the wires and bulb filament. Some of the energy of the electrons is converted, making the ions vibrate more. The vibrating ions can convert this energy into the form of heat and/or light. The electrons are still under the influence of the battery so continue to move on, colliding with other ions in the wires and bulb filament. Because of the nature of the filament wire in the bulb, the collisions result in a large conversion of energy. The whole wire heats up and the bulb lights. In the connecting wires, the energy conversion is much less and so much less heating occurs. In other words, most of the energy conversion occurs in the filament wire in the bulb. It is very important that students are not left with the idea that an electron leaves the negative terminal of the battery runs through the wires with the speed of light to reach the positive terminal. The free electrons in the wire are moving in a motion similar to Brownian Motion. This is called thermal motion and is of the order of several thousand metres per second. They are continuously colliding with ions, losing energy and regaining it from the electric field. Imposed on the thermal -6- JSSS Teacher support material motion is a slow drift towards the positive terminal. This drift velocity is of the order of millimetres per second. It takes hours for an individual electron to move through a metre of wire. But the electric field moves at the close to the speed of light, causing the bulb to light almost immediately that the circuit is complete. This can be demonstrated using a clear plastic tube and some golf balls. Fill the tube with golf balls. If a ball is now pushed into the tube, all the balls in the tube move at the same time and at the same speed. The coloured golf ball can be seen to move slowly along the tube but the effect is observed almost immediately at the left end of the tube when a ball is introduced on the right. Squeezing the tube can introduce the idea of resistance. The drift of electrons constitutes an ‘electric current’. The greater the drift velocity of the electrons, the greater is the electric current. Convention states that current is in the opposite direction to the drift motion of the electrons, i.e., electric current is from positive to negative. Note: In metallic conductors, the charge carriers are normally electrons. In the battery or cell, the charge carriers are ions. Ions also carry the charge in solutions of electrolytes. (OC34, OC44, OP53) Voltage When a battery is in use, chemical energy is converted into electrical energy. Chemical reactions are going on inside the battery. These reactions release and absorb electrons. They are also the source of energy which maintains a drift of electrons in the circuit as long as the reactions continue. The battery is said to have a potential difference (p.d.) between its terminals. Potential difference is measured in volts (V). The term voltage is often used instead of potential difference. In an electric circuit, the battery is the source of energy for the free electrons throughout the circuit. This energy can be converted into other forms of energy, such as heat and light, at points in the circuit. The unit of electric charge is the coulomb (the charge on about 6×1018 electrons). The voltage of the battery is a measure of how much energy is transferred by the battery to every coulomb of unit of charge. Energy is converted by the battery to the electrons at all points in the circuit. This is converted to other forms of energy at places where the electrons meet resistance. The potential difference or voltage between two points in a circuit is a measure of the amount of energy being converted by each coulomb. If there is a potential difference (voltage) of 6 volts between the terminals of a battery, this means that 6 joules of energy are converted by the battery for each unit of charge (coulomb). -7- JSSS Teacher support material If the potential difference (voltage) between the ends of a resistor in a circuit is 4 volts, this means that for each unit of charge 4 joules of energy are converted in the resistor. The sum of all the potential differences (voltages) around a series circuit must be equal to the total amount of energy converted by the battery, so complying with the Principle of Conservation of Energy. The greater the resistance an electron meets, the more energy is converted. There is twice as much energy converted in a 20 Ω resistor as in a 10 Ω resistor in the same series circuit. The current is the same at all points in the circuit, i.e., the rate of flow of charge is the same. To maintain the uniform rate of flow in this circuit, twice as much energy is converted in the 20 Ω resistor as in the 10 Ω resistor. The potential difference (voltage) between the ends of the 20 Ω resistor is twice what is between the ends of the 10 Ω resistor. The resistance of the connecting wires is negligible and so the amount of energy converted in them is negligible. 6V Each coulomb gains 6 joules of energy from the battery 6V 20 Ω 10 Ω 4V 2V 4 joules of energy are converted for each coulomb 2 joules of energy are converted for each coulomb Each coulomb gains 6 joules of energy from the battery 6V 6 joules of energy are converted for each coulomb If there was only one component, e.g. a bulb, in the circuit, all 6 joules would be converted there. The more items that are in the 6 V series circuit, the less energy will be converted at each as there are only 6 joules to be shared between them. The energy is converted in direct proportion to the size of the resistance of the items. In the parallel circuit shown below, all the components convert the same amount of energy from each coulomb that passes through them – the amount the coulomb gains from the battery, i.e., 6 J. The potential difference (voltage) between the ends of each resistor is the same, i.e., 6 V It is important to note that the number of coulombs flowing through each resistor per second will depend on the value of the resistor. The biggest resistor will have the smallest current. -8- JSSS Teacher support material I = I1 + I2 6 joules of energy are converted for each coulomb I2 6V 6 joules of energy are converted for each coulomb I1 6V I 6V Each coulomb gains 6 joules of energy from the battery Potential difference is measured using a voltmeter. The voltmeter is always connected in parallel with that part of the circuit where the potential difference is to be measured. Note: The volt is defined as follows: The p.d. (voltage) between two points in a circuit is 1 volt if 1 joule of electrical energy is converted into some other form when a charge of 1 coulomb passes between the two points. R Resistance Electrons move more easily through some conductors than others when a potential difference is applied. The opposition to electric Ω current is called resistance and is measured in ohms (Ω). The resistance of a piece of conducting wire depends on three things length cross-sectional area material Ohmmeter A long wire has more resistance than a short one of the same material and thickness. A thin wire has more resistance than a thick one of the same material and length. Copper is commonly used in connecting wires as it is relatively cheap. Aluminium is also used. Other metals such as silver are better conductors than both of these, but are not generally used for economic reasons. The resistance of a metallic conductor is also affected by heat. Resistance increases with temperature. It is important to be aware of this when investigating current in bulbs,etc. Resistance is measured using an ohmmeter. An Ohmmeter is connected in parallel with the component whose resistance is to be measured. The component should not be in a working circuit when its resistance is being measured. The ohmmeter has its own power supply and could be affected by another supply in the circuit. This would lead to incorrect values being obtained for resistance. -9-