Cross-Cultural Approaches to Work Family Conflict

Cross-Cultural Approaches to WFC

Invited Presentation at the Arab Women Leadership Forum, 12-13 January 2010

Work Family Conflict from a Cross-Cultural Perspective

Zeynep Aycan, Ph.D.

Department of Psychology

Koç University, Istanbul zaycan@ku.edu.tr

Abstract

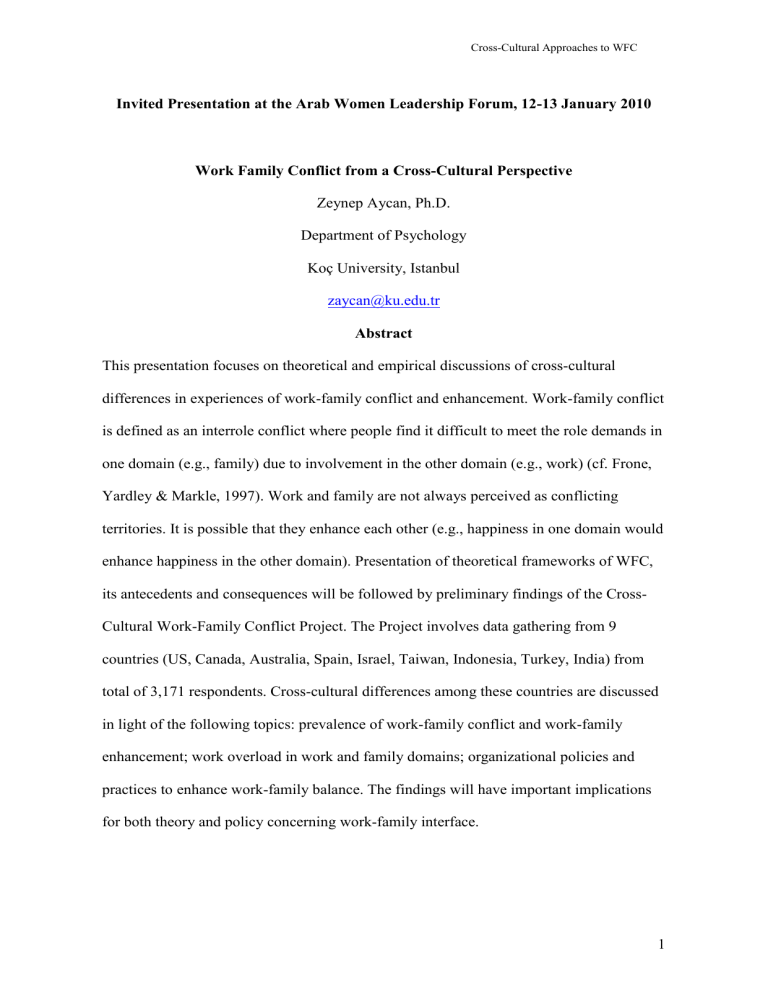

This presentation focuses on theoretical and empirical discussions of cross-cultural differences in experiences of work-family conflict and enhancement. Work-family conflict is defined as an interrole conflict where people find it difficult to meet the role demands in one domain (e.g., family) due to involvement in the other domain (e.g., work) (cf. Frone,

Yardley & Markle, 1997). Work and family are not always perceived as conflicting territories. It is possible that they enhance each other (e.g., happiness in one domain would enhance happiness in the other domain). Presentation of theoretical frameworks of WFC, its antecedents and consequences will be followed by preliminary findings of the Cross-

Cultural Work-Family Conflict Project. The Project involves data gathering from 9 countries (US, Canada, Australia, Spain, Israel, Taiwan, Indonesia, Turkey, India) from total of 3,171 respondents. Cross-cultural differences among these countries are discussed in light of the following topics: prevalence of work-family conflict and work-family enhancement; work overload in work and family domains; organizational policies and practices to enhance work-family balance. The findings will have important implications for both theory and policy concerning work-family interface.

1

Cross-Cultural Approaches to WFC

“Work and family – almost conflict in terms”

(An Australian woman)

“Work and family: salt and pepper of life”

(A Taiwanese woman)

“I work for my own personal well-being. I cannot waste my years of education”

(An

American woman)

“My family is my priority; I do everything for them – I work like crazy so that they don’t have to go through the difficulties that I have gone through in life”

(A Chinese men)

“My mother-in-law said when we had our first child, ‘Do the tigers give their babies to the elephants to get raised? Do the elephants ever give their babies to the lions to get raised?’ I thought ‘Oh gosh, I better stay at home with my own kids’”.

(An American woman; from

Joplin, Shaffer, Francesco, Lau, 2003)

“My mother-in-law almost got fainted when I told her that I wanted to give my child to daycare. She took it as the biggest insult to herself”

(A Turkish woman)

Work-family conflict (WFC) is a common phenomenon of modern life in many countries and cultural contexts. However, as the above quotations demonstrate, the perception and prevalence of WFC, its antecedents and consequences tend to vary across cultures. According to Russell and Bowman “global organizations have realized that there is a need to understand variations in work/family issues from one country or region to another, and what the key drivers of these variations are” (2000, p.124). Understanding cultural differences in WFC is necessary not only for global organizations (e.g., MNCs), but also for domestic organizations with a multicultural workforce. To effectively manage diversity, these organizations seek to develop policies to balance work and family that are sensitive to cultural differences. Studying the influence of culture on WFC will also help

2

Cross-Cultural Approaches to WFC managers in non-Western contexts (e.g., emerging economies), who are in need of understanding the applicability of WFC models and policies that are developed in Western industrialized societies. Cross-cultural studies, therefore, will contribute to practice and policy development, and enhance theory building by introducing the boundary conditions

(i.e., cultural contingencies) in conceptualizing the WFC phenomenon and arriving at a more universal knowledge (Gelfand & Knight, 2005).

This paper aims at providing a review of the cross-cultural literature and providing first findings of our cross-cultural research. How does culture influence WFC? The model presented in this paper (Figure 1) is based on the theoretical model of the International

Work-Family Conflict Project (Project 3535). This project aims at testing the Frone,

Yardley and Markle’s (1997) integrative model of WFC in ten cultural contexts (i.e., US,

Canada, Spain, Australia, the Arab sect of Israel, the Jewish sect of Israel, Indonesia,

India, Taiwan, and Turkey)(Aycan, Ayman, Bardoel, Desai, Drach-Zahavy, Hammer,

Huang, Korabik, Lero, Mawardi, Poelmans, Rajadhyaksha, Shafiro, Somech, 2004;

Korabik, Lero, & Ayman, 2003).

Table 1. Sample size for each country included in Project 3535. country Male female total

Australia 86 123 209

Canada

India

Indonesia

Israel

US

Spain

349

276

137

118

95

79

303

300

175

118

286

118

652

576

312

236

381

197

Taiwan

Turkey

Total

77

165

1382

205

161

1789

282

326

3171

3

Cross-Cultural Approaches to WFC

Type of support

Satisfaction with support

Source of support

Work

Support

Guilt

Satisfaction with family

Work

Demands

Work interfering family

Negative

Family Outcomes overload involvement control

Psychological

Well-Being control involvement overload

Family

Demands

Family

Interfering

Work

Negative Work

Outcomes

Job satisfaction

Turnover intention

Family

Support

Type of support

Satisfaction with support

Source of support

Figure 1. Theoretical Model of Project 3535 (based on Frone, Yardley & Markle, 1997)

Cross-Cultural Differences in WFC

There is research to suggest that WFC is construed in different ways across cultures. For example, the work and family domains are perceived to be segmented in the

US, but integrated in China (Yang, 2005). Because of the perception of segmentation, work and family roles are considered to be incompatible, rather than congruent . Role incompatibility leads to experiences of conflict in the US, whereas role integration leads to experiences of balance in Hong Kong (Joplin, Shaffer, Francesco, & Lau, 2003).

Findings of our cross-cultural project suggested that type of interrole conflict experienced by employees also varied across cultures. For example, the roles of employee and parent are seen as conflicting in Israel, Singapore and India; the employee and

4

Cross-Cultural Approaches to WFC homemaker roles are viewed as conflicting in the Arab sect of Israel, Singapore and India; the roles of employee and spouse are seen as conflicting in Singapore and India; and roles of employee and social woman (e.g., organizing and attending social events and functions) are viewed as conflicting in the Arab sect of Israel and Indonesia. The crosscultural differences in the strength of various interrole conflicts could be a function of the salience of different roles in societies. For example, if the role of a woman in the Arab culture as a good housewife and a social woman is very strong, then it is more likely that the interrole conflict would be experienced between job and homemaker roles or between job and social woman roles. In summary, the job role conflicts with the social roles that are most salient in societies. We also found that work-family conflict is experienced to a greater extend than work-family enhancement (also referred to as positive spillover) in economically developed countries (Figure 2).

4,5

4

3,5

3

2,5

2

1,5

1

0,5

0

Indonesia India Taiwan Turkey Israel Spain Canada US Australia

WIF FIW Positive Spillover

Figure 2. Findings of Project 3535 pertaining to cross-cultural differences in workinterfering-family (WIF), family-interfering-work (FIW), and work-family enhancement

(positive spillover).

5

Cross-Cultural Approaches to WFC

Cross-Cultural Differences in the Demands Leading to WFC

How does the cultural context influence the type and strength of demands in the work and family domains? Among the most highly cited demands in the work and family domain is the work overload. Work overload is the perception that one has too much to do

(Leiter & Schaufeli, 1996). Work overload was found to be one of the strongest correlates of WFC (e.g., Aryee et al., 1998; Britt & Dawson, 2005; Mckay et al., 1999). A person may experience work overload because of high number of tasks or low level of resources

(time, budget, manpower) available to complete the tasks. Mesmer-Magnus and

Viwesvaran (2005) found that work overload is the demand that had the strongest correlation with WFC. Work overload aggrevates WFC, because an employee spends more time at work to finish tasks and less time at home. This is referred to as time-based work-family confict (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). Even if the employee spares time for family, physical and emotional exhaustion caused by overload decrease the quality of time spent with family (Britt et al., 2005; Leiter & Schaufeli, 1996). Strain caused by work overload may interfere with the functioning in the family, and this is referred to as strainbased conflict (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). We, therefore, expect work overload to have a positive relationship with WIF. Work overload will interfere with personal life for the same reasons. Employees experiencing work overload will not be able to spend time for their personal lives.

6

Cross-Cultural Approaches to WFC

Cross-cultural differences in overload in work and family domains in our research suggest that overload in family is slightly more experienced than overload at work, and that overload in both domains aggravate WFC in all countries.

4,5000

4,0000

3,5000

3,0000

2,5000

2,0000

1,5000

1,0000

,5000

,0000

In do ne si a

Sp ai n

C an ad a

US

Isra el

Tu rke y

Au st ra lia

Ta iw an

In di a

Overload - work overload - family

Figure 3. Cross-cultural difference in the report of work and family overload.

Cross-Cultural Differences in the Availability and Use of Family-Friendly

Policies and Practices

The following chart presents the answers of participants to the following question:

“Please indicate the extent to which the workplace practice cited in this question helped you to maintain work-family balance when you used it” (1 = not at all helpful; 5 = extremely helpful). It appears that not all countries find the workplace practices equally helpful to enable them to establish the work-family balance. For example Indonesian respondents implied that such practices were not helpful to improve their work-family balance. Similarly, not all practices were equally helpful. For example, home office was not a practice that was perceived to be extremely helpful in balancing work and family.

7

Cross-Cultural Approaches to WFC

1,5

.

1

0,5

0

5

4,5

4

3,5

3

2,5

2 fle xib le

w or k h o ur s re d uc ed

w o rk

w ee k ho m e o ffi ce ex tr a m ate rn ity

le av e ch ild

c ar e i n th e w or kp la ce

Indonesia India Israel Canada Taiwan Australia US Spain Turkey

Figure 4. Cross-cultural differences in the perceived helpfulness of organizational practices to enhance work-family balance (note that none of the Australian participants reported using home office and childcare facilities).

8

Cross-Cultural Approaches to WFC

4

3,5

3

2,5

2

1,5

1

0,5

0

S ati s.

O na l P

&

P

S ati s.

G ov er n.

P

&

P

Taiw an Spain Turkey Canada Indonesia Israel US Australia India

Figure 5. Cross-cultural differences in satisfaction with organizational (Onal.) and governmental (Govern.) policies and practices to enhance work-family balance.

Summary and Implications

The aim of this paper was to present the preliminary findings of the crosscultural WFC project. It appears that there are differences among countries in the prevalence of work-family conflict and work-family enhancement. Economically developed countries report negative spillover (WFC) more than positive spillover (workfamily enhancement). Overload in both work and family domains seem to be responsible for WFC in all countries. Among the organizational practices, home office appears to be the least useful, and flexible work hours and extra maternity leave allowance seem to be the most useful practices to facilitate work-family balance. In general, participants from the economically developed countries (with the exception of India) were more satisfied with organizational and governmental policies and practices to enhance work-family

9

Cross-Cultural Approaches to WFC balance than were economically developing countries. The findings will be discussed in light of culture and economic development.

References

Aryee, S., Luk, V., Leung, A., & Lo, S. (1998). Role stressors, interrole conflict, and wellbeing: The moderating influence of spousal support and coping behaviors among employed parents in Hong Kong. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 259-278.

Aycan, Z., Ayman, R., Bardoel, A., Desai, T. P., Drach-Zahavy, A., Hammer , L.

Huang, T. P., Korabik, K., Lero, D. S., Mawardi, A., Poelmans, S. A. Y.,

Rajadhyaksha, U., Shafiro, M., Somech, A. (2004). Work-family conflict in cultural context: A ten-country investigation. Paper presented at the 19th Annual

SIOP Conference, Chicago, April.

Britt, T. W., & Dawson, C. R. (2005). Predicting work-family conflict from workload, job attitudes, group attributes, and health: A longitudinal study. Military Psychology,

17 (3), 203-227.

Joplin, J.R.W., Shaffer, M.A., Francesco, A.M., & Lau, T. (2003). The macro environment and work-family conflict: Development of a cross-cultural comparative framework. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management , 3

(3), 305-328.

Gelfand, M.J., & Knight, A. P. (2005). Cross-cultural perspectives on work-family conflict. In S. A. Y. Poelmans (Ed.). Work and family: An international research perspective (pp. 401- 415). London: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10, 76-88.

Frone, M.R., Yardley, J.K. and Markle, K.S. (1997). Developing and Testing an

Integrative

Model of Work–Family Interface. Journal of Vocational Behavior 50: 145–67.

Korabik, K., Lero, D.S., & Ayman, R. (2003). A multi-level approach to cross-cultural work-family research: A micro- and macro- perspective. International Journal of

Cross-Cultural Management, 3 (3) , 289-303.

Leiter, M. P., & Schaufeli, W. B. (1996). Consistency of the Burnout Construct Across

Occupations. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 9, 229-243.

Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., & Viwesvaran, C. (2005). Convergence between measures of work-to-family and family-to-work conflict: A meta-analytic examination. Journal of Vocational Behavior,67, 215-232.

Yang, N. (2005). Individualism-collectivism and work-family interface: A Sino-US comparison. In S. A. Y. Poelmans (Ed.). Work and family: An international research perspective (pp. 287-319). London: Lawrence Erlbaum.

10