Final Draft

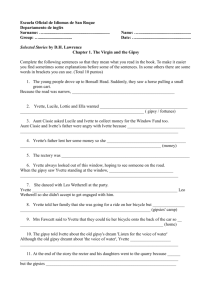

advertisement

Nero 1 I. Introduction: A. Thesis: In the short novel The Virgin and the Gipsy, D. H. Lawrence explores many issues that plague modern society; through his detailed progression of Yvette’s infatuation with the gipsy, he introduces a hidden theme: the effect of time on a woman’s beauty and status. Wurtzel, Elizabeth. Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women. New York: Random House, 1998. Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. Trans. H. M. Parshley. New York: The Modern Library, 1968. B. Subtopics: 1. : Yvette as a Virgin i. She-who-was-Cynthia 2. : Yvette’s Progression into Desirableness/ Realization of Desire 3. : Desire defined 4. : Loss of Desire C. Type of Grabber/Hook: Fancy language and interesting feminist issue. II. Development of Subtopics: A. Subtopic 1: At this point in the novel, Yvette is still young, impressionable, and virginal; she shows this through her insecurities and rash actions. Lawrence, D.H. The Virgin and The Gipsy. Vol. 2 of Short Novels. 3 Vols. London: Windmill Press LTD, 1956. i. She-who-was-Cynthia’s effect on the family and on Yvette’s development. Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. New York: Norton, 1963. B. Subtopic 2: Then, after returning home and reflecting on the mysterious gipsy, Yvette recognizes his desire for her. Leavis, F. R. D. H. Lawrence: Novelist 1955. Rt. In Vol. 2 of TwentiethCentury Literary Criticism. Ed. Dedria Bryfonski and Sharon K. Hall. Detroit: Book Tower, 1979. 360-364. ---. Assorted Articles. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928. Nero 2 C. Subtopic 3: Lawrence states that desirableness makes the woman. ---. Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1963. D. Subtopic 4: The Virgin and the Gipsy ends as Yvette transforms once more into the stage symbolic of a woman’s old age. Siegel, Carol. Lawrence Among The Women: Wavering Boundaries in Women’s Literary Traditions. Charlottesville: The UP of Virginia, 1991. III. Conclusion A. Summary B. Logical Conclusion Nero 3 Willow Nero University English II Mr. Jack L. Carter December 7, 2004 The Theme of a Woman’s Fleeting Existence in Lawrence’s The Virgin and the Gipsy In the short novel The Virgin and the Gipsy, D. H. Lawrence explores many issues that plague modern society; although, through his detailed progression of Yvette’s infatuation with the gipsy, he introduces a hidden theme: the effect of time on a woman’s beauty and status. At the start of the novel, Yvette is a young, innocent virgin. As the story progresses and she meets the gipsy, Yvette wanders from the closed world of the rectory and eventually she loses her symbolic virginity, or the qualities that make her virginal in the story. This transformation is symbolic of the transformation that all women endure as age overcomes beauty and their value to society diminishes. Elizabeth Wurtzel describes this haunting feminist issue in her book Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women. She says, “unlike men, …women age into insignificance. …Feminism wants to pretend we have forever, but we don’t. Men do” (405). Renowned Nero 4 French feminist writer Simone de Beauvoir takes issue with this unfair and short-lived life of the woman. She writes: Whereas man grows old gradually, woman is suddenly deprived of her femininity; she is still relatively young when she loses the erotic attractiveness and the fertility which, in the view of society and in her own, provide the justification of her existence and her opportunity for happiness. (575) Many other feminists take this stance, disgusted that the female livelihood is defined by such a fickle principle of lust. Through D. H. Lawrence’s The Virgin and the Gipsy, he tells the story of a young virgin who finds this lusty desire in herself and then loses it, portraying the sad fate of women. Lawrence starts out The Virgin and the Gipsy, describing Yvette as a “younger girl” with “vague… careless blitheness” (6). She is obviously the cosseted virgin. Of the rector’s two daughters, Yvette displays the most qualities of her “delinquent” mother, “the pure white snow-flower” (4) who was once married to the rector but ran away and is now known only as She-who-was-Cynthia. Because the rector sees these traits in Yvette, he shields her from the outside world, with hopes that Yvette will never become as tainted as her mother. Lawrence even reveals that “[the rector] was afraid his daughter was developing something of the rank, tainted qualities of She-who-was-Cynthia” (26). She-who-was-Cynthia in The Virgin and the Gipsy symbolizes the apex of feminine beauty and charms. Cynthia left the world of the rector and went in search of “something more than [her] husband and [her] children and [her] home” (Friedan, 32), a phenomenon Nero 5 that Betty Friedan found to be the antithesis of “the feminine mystique,” or the urge to uphold a family and surrender individuality. Yvette’s father cannot lose another woman to this power so he keeps her at home and teaches her to date the young men he chooses. Yvette is destined to lose her innocence and learn to use her feminine charms, but her family situation has set up a trap so that she will fall forever into the nothing existence of the housewife.PROOF Yvette will not get away as Cynthia did; Yvette’s individuality, self-image, and essentially her will to live are sacrificed to society’s female role. Yvette shows her young, impressionable, virgin state through her insecurities and rash actions. Yvette fights with her grandmother over the temperature in the room with the window open and breaks into a yelling fit. Lawrence hints at a virginal force “deep inside her [that] worked an intolerable irritation, which she thought she ought not to feel, and which she hated feeling” (10). Yvette’s wondering mind driven by this angst coaxes her to leave the house in search of something with her friends. Yvette first comes in contact with the gipsies while stopping with friends to hear her fortune. The motherly gipsy figure offers Yvette to step inside the caravan to have her fortune told, but Yvette cannot make up her mind and instead lets the woman decide for her. Lawrence says that Yvette feels “wayward, perverse” (23) about the decision. Here her virginity is a force she must fight with and that causes her angst, but it is also a source of her childlike tranquility. In one of her meetings with the gipsy, Yvette is almost drunk in her own virginity: On her face was that tender look of a mysterious early flower, she was full out, like a snowdrop which spreads its three white winds in a flight into the waking Nero 6 sleep of its brief blossoming. The waking sleep of her full-opened virginity, entranced like a snowdrop in the sunshine was upon her. (48) The gipsy is “aware of one thing only, the mysterious fruit of her virginity, her perfect tenderness in the body” (48). Yvette is hardly aware of this mysterious fruit and watches the gipsies in awe. F. R. Leavis asserts that The Virgin and the Gipsy “focuses in the look Yvette catches in the eyes of the gipsy, and the effect it has on her. The tale is concerned with defining and presenting desire as something pre-eminently real” (364). In her first encounter with the young male gipsy Yvette notices “something peculiarly transfusing in his stare.” She “felt it, felt it in her knees” (21). Then, after returning home and reflecting on the mysterious gipsy, Yvette recognizes his desire for her: And the gipsy man himself! Yvette quivered suddenly, as she had seen his big, bold eyes upon her, with the naked insinuation of desire in them. The absolutely naked insinuation of desire made her lie prone and powerless in the bed, as if a drug had cast her in a new, molten mould. (30) Yvette, now fully aware of her sex and desirableness, yearns to know if the gipsy wants her. Through other encounters with the male gipsy, Yvette learns to flaunt her desirable qualities in a way that the gipsy responds to them. Lawrence reveals, “a good-looking woman becomes lovely when the fire of sex rouses pure and fine in her and flickers Nero 7 through her face and touches the fire in [a man]” (“Sex Versus Loveliness,” 27). Yvette has reached this stage with her desirableness in The Virgin and the Gipsy where she can easily arouse these types of feelings in the gipsy. Lawrence states that desirableness makes the woman: “You can see it in every step she takes. She is desirable. And this is the breath of her life” (“Love was once a Little Boy…” 175). Yvette feels this transformation in conversation with her sister Lucille. Lucille and Yvette discuss marriage and sex, which they decide brings two people together. Lucille feels that it is an awful convention that something so common and low is all that connects a marriage. Yvette agrees, saying, “Perhaps we haven’t really got any sex, to connect us with men” (55). Then, Yvette thinks to herself that this is untrue for “Far in the background was the image of the gipsy as he had looked round at her” (55). Yvette’s apprehension in allowing her sister to learn of her love for the gipsy is significant in that it proves her loss of innocence. Lucille can only speak out of experience and she has no experiences with men to believe that marriage is otherwise; Yvette,P on the other hand, has lost her virginity to the gipsy and feels the need to be desired. This stage of Yvette’s desirableness marks the height of her, and women’s, potency in life. The Virgin and the Gipsy ends as Yvette transforms once more into the stage symbolic of a woman’s old age. Without her virginity and desirableness in the way, Yvette feels that she has less for which to live. Yvette awakens the morning after her gipsy has saved her from a flash flood to a policeman in her bedroom, and can only think, “Where was the gipsy? Where was her gipsy of this world’s-end night? He was gone! He was gone” (79)! Lawrence declares, “the grief over him kept her prostrate” (81). It is Nero 8 not until a letter arrives in the mail that Yvette hears of the gipsy again, but her love for him is diminished when she reads his name. Yvette’s gipsy is no longer a fairy-tale innocent crush, but his name is Joe Boswell. Carol Siegel describes Yvette’s encounter as “the wave of desire, invulnerable as long as she defies social rules to express it, because nature takes her part against man’s world” (172). Receiving the letter from the gipsy marks the point where Yvette descends from her highly attractive state of desirableness to the less-coveted role as a common woman. Social rules describe her relationship to the gipsy now that he has a name; Yvette’s fantasy is over. This transition through a loss of innocence is symbolic of the transition women must face in the mirror of time. Lucille and Yvette talk together on the subject of marriage and Yvette finds a frustration in her state with which many women identify: “I think it’s time to think of marrying somebody,” said Lucille, “when you feel you’re not having a good time anymore. Then marry, and just settle down.” “Quite!” said Yvette But now, under all her bland, soft amiability, she was annoyed with Lucille. Suddenly she wanted to turn her back on Lucille. (57) Yvette transforms in The Virgin and the Gipsy from the virgin, to the object of desire, and then into the outcast refuse of society. As Elizabeth Wurtzel describes this event, “Time is not on our side, our youth and beauty is brief, tick-tock the biological clock, and that message is thrown at us over and over again” (26). D. H. Lawrence Nero 9 throws this message once more upon the reader, outlining this desirableness that is “like a delicate flame” (“Love was once a Little Boy…” 176). Depressingly he says, “we have imagined love to be something absolute and personal. It is neither. In its essence, love is no more than the stream of clear and unmuddied subtle desire which flows from person to person, creature to creature, thing to thing. Desire is either flowing, or gone, and the love with it, and the life too” (“Love was once a Little Boy…” 176). Superior Essay! I would think you would show a bit more critical acumen in your analysis of this material. Lawrence makes a distinction between the power of “love,” the arch in The Rainbow and lust in your story and others. Like many other twentieth century writers, Lawrence wants to define sexual desire in terms outside of morality. The influence is Darwin. I would suggest that such analyses ignore the natural roles of different age groups in life. In other cultures and past cultures, the role of “grand” mother is that of a rich source of love and inspiration. That role has been lost in favor of a return to youth or the refusal to accept the changes wrought by time: the source of a great deal of pain and suffering in the name of freedom. Nero 10 Works Cited Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. Trans. H. M. Parshley. New York: The Modern Library, 1968. Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. New York: Norton, 1963. Lawrence, D. H. Assorted Articles. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928. ---. “Love was once a Little Boy.” Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1963. ---. The Virgin and The Gipsy. Vol. 2 of Short Novels. 3 Vols. London: Windmill Press LTD, 1956. Leavis, F. R. D. H. Lawrence: Novelist 1955. Rt. In Vol. 2 of Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism. Ed. Dedria Bryfonski and Sharon K. Hall. Detroit: Book Tower, 1979. 360-364. Siegel, Carol. Lawrence Among The Women: Wavering Boundaries in Women’s Literary Traditions. Charlottesville: The UP of Virginia, 1991. Wurtzel, Elizabeth. Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women. New York: Random House, 1998.