University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire

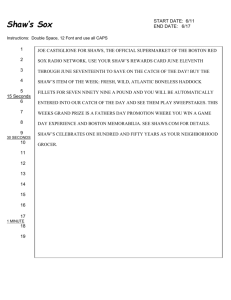

advertisement