extending the product process diagonal

advertisement

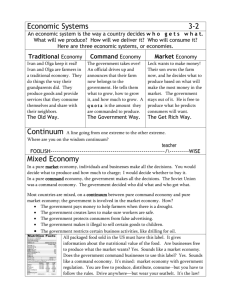

EXTENDING THE PRODUCT PROCESS DIAGONAL TO SERVICE ORGANIZATIONS Tony Polito, Terry College of Business, 260F PE Building, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, 30602, 706.542.3751 ABSTRACT The explanatory power of the product process matrix does not include current industry trends to increase the service content of goods. When the matrix is coupled with the works of Schmenner and Sasser, an expanded framework emerges that fits well with many existing service classification schemes. TREND TO SERVICE VIA CUSTOMIZATION A number of Original Levi's retail outlets now offer made-toorder women's bluejeans on a mass customization basis. Customer measurements are entered at the POS terminal and directed to a numerically controlled cutting device at the company's Tennessee plant. Levi's customization strategy effected a 300% increase in sales and a simultaneous reduction in inventory at introduction. Currently, the company is codeveloping a POS "body scanner" expected to decrease response time and improve the quality of the process [14]. The application is not unique; Tom Peters notes a similar process for the tailoring of suits at Saks Fifth Avenue [15]. Anderson windows, Motorola pagers, and Hallmark Create-A-Card vending machines provide examples of mass customization from other industries. Even McDonald's, the bellwether of Levitt's industrialized service, now carries hundreds of menu items targeted by region, rotates specialty items seasonally or monthly, and offers its once standardized burgers on an assemble-to-order basis. In some ways, mass customization implies a shift towards craft shop production, including higher product heterogeneity and increased levels of customer involvement, specification, and delivery convenience. However, it also expects increased volumes, economies of scale, capitalization, and commoditylike behaviors, as found in flow production of goods. These contradictions in the trend to mass customization represent directly opposing shifts along the main diagonal of the product process matrix developed by Hayes and Wheelwright to depict the relationship between a product's growth and volume and its process technology. The matrix, now accepted as a standard framework, is robust with implications for strategy, operations, and marketing. Here, however, it falters under the higher service content of the mass customized product. Increased volumes, economies of scale, capitalization, and commodity-like behaviors do, however, represent an outward shift along the diagonal within the service process matrix, developed by Schmenner for equivalent analysis of service products and processes. REVIEW OF RECENT SERVICE PERSPECTIVES Hill's economic analysis of goods and services provides a foundation for synthesis. Both goods and services are transaction-based; the transfer of ownership identifies a good, and the change in the condition of an object identifies a service. Hill's perspective allows for the bundling of goods and services within a single product transaction; a position supported by numerous researchers [2] [4] [5] [8] [9] [16] [17] [19]. Advocacy for bundling from a practitioner perspective is exemplified by Lexus management, recently defining its product, not as a good, but as a luxury service package. Hill also recognizes the potential utility of a good or service, and delineates it from the underlying transaction; the interpretation of service as consumers transacting for utility finds modern support as well [7] [13]. If both goods and services are viewed by consumers as creating utility, then a single product variously bundled with proportions of goods and services allows for the efficient and rational consumer to effect equivalent utility substitutions, eg, grocery stores versus restaurants in the case of food products. Therefore, a specific product should be viewed on a continuum representing its relative proportion of goods and services, a conclusion reached by others [16] [17] [19]. Bell [2] jointly classifies goods and services within a 2 x 2 continuum based on levels of tangibility and customer involvement. The main diagonal moves from highly tangible, low involvement products, referred to as commodity-like "pure" goods, eg, rolled steel, to highly intangible, high involvement products, titled customized service. The central point is described as a bundle of goods and services bearing a median level of product differentiation. Later work by Bell [1] explores the strategic implications of repositioning a product along the diagonal via bundling. Bell's classification offers a "goods" diagonal that bears resemblance to the product process diagonal, coupled to a equivalent diagonal for services, resulting in a continuum of bundled goods and services. Schmenner [18] expands the perspective within a 'service process' matrix that dichotomizes the degree of such interaction and customization by the degree of labor intensity. Professional service firms are characterized by high degrees of interaction, customization, and labor intensity; service factories, by low degrees. Service shops have low labor content, but a high level of customization; mass services, the reverse. Schmenner characterizes this work as a clear services parallel to the Hayes and Wheelwright matrix for manufacturing [6], eg, that increasing interaction and customization causes the service factory to give way to the service shop in similar manner as continuous flow gives way to job shop manufacturing. Schmenner also notes the attraction of services toward, and movement along, the main diagonal from 'professional service' to 'service factory,' and the related strategic implications of such positioning. Chase [3] proposes a service diagonal similar to that of Schmenner within a 'service system design matrix' to integrate marketing and operational strategy, which he credits as strongly influenced by the product process matrix. Though abbreviated herein, the review of service typologies consistently identifies two perspectives with broad and continuous support, ie, a product continuum containing bundled goods and services and a service classification scheme which mirrors the Hayes and Wheelwright diagonal. elusive, the attributes are also significant for empirical research. The content continuum still contains the strategic implications of previous research. Positioning towards the continuum is effected within the framework of the product or service process matrix; repositioning along the continuum reflects an altering of the proportional content of goods and services as well as changes in volume and process. Pure goods contain the lowest levels of total customer affinity, product customization, needs determination by consumer, product durability, product heterogeneity, customer participation, customer as object of utility creation, economy of scope, and hierarchical needs levels fulfilled; pure services, the highest levels. Both pure goods and pure services contain the lowest levels of labor intensity, employee / customer physical contact; good/service bundles, the highest levels. Both pure goods and pure services contain the highest levels of capital intensity, product volume, proximity of delivery, process stability, operational standardization and efficiency, and commodity attributes; good/service bundles, the lowest levels A CONTENT CONTINUUM HARMONY WITH OTHER TYPOLOGIES These two perspectives suggest a single "content continuum" embracing both the Hayes & Wheelwright and the Schmenner diagonals, in the manner concisely illustrated below as Figure 1. There appears to be a high degree of concordance between the content continuum and the existing body of knowledge in service classification; Figure 2 equates, in an abbreviated manner, the continuum with a few of the more visible schemes (though some typologies are mirrored or extended by degree in order to encapsulate both goods in addition to services.). CONCLUSION FIGURE 1 Content Continuum Product Process Diagonal (Hayes & Wheelwright) Continuous Flow Job Shop Service Process Diagonal (Schmenner) Professional Service Service Factory Pure Goods Pure Service Product as %age of Goods and Services (Sasser) To exemplify, consider a continuous flow commodity good at left that contains relatively little service, while a resort, eg, Disney World, positioned at right, produces relatively little goods, rather a highly customized service. At left of center, the traditional print shop product is primarily a good bundled with facilitating services; At right of center, professional firms provide services bundled with facilitating goods, eg, accountants and prepared tax returns. This content continuum moves from uniform commodity goods to unique commodity services across the two previous frameworks. A number of attributes to facilitate a deeper intuitive understanding of the continuum are offered below. Since measurement of proportional service content may prove Though this framework does not provide a single multidiscipinary model required under service, a return to the motivational example of custom-cut bluejeans illustrates useful inference. The continuum suggests proximate distribution for higher customer convenience; the location of a POS body scanner, if fully automated, within a traditional retail outlet becomes arbitrary. Such a device could be situated anywhere target markets flow; the notion is barely more extravagant than the decisive strategy that placed hosiery displays within supermarkets. Incremental emphasis on service flow strategy might include a more capable device to allow for complimentary goods, eg, blouses and slacks, and greater consumer needs determination, eg, styles and fabrics, furthering an economy of scope. Direct effects of such a strategy include lower labor intensity and physical contact, [3] FIGURE 2 Continuous Flow Job Shop Professional Service Service Factory Pure Goods Pure Service Product as %age of Goods and Services (Sasser) [4] [5] Distribution, Lovelock [10] [11] at producer at mutual at customer convenience convenience convenience [6] [7] Workflow Interface, Mills and Marguiles [12] MaintTask Personal Task Maintenance interactive interactive interactive enance interactive goods goods and services interactive goods / or services services Customer Contact vs. Economic Concentration, Stiff and Pollack [20] Low contact, High contact, low Low contact, high concentration high concentration goods and / or concentration goods services services Object of Service, Lovelock [10] [11] Goods and Intangible People's People's physical assets bodies charminds (perpossessions acteristics) ceptions) with higher customer participation, capitalization, and degree of flow. As competitors duplicate such technology, consumers could be expected to treat the product much like a commodity, requiring marketing efforts to enhance the depth of the customer relationship sufficiently to ensure the next purchase. Even this brief example effectively suggests that the content continuum is generally robust enough to provide management with insight into the manufacturing, marketing, and strategic implications of its decisions regarding the service content of its products. [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] REFERENCES [1] [2] Bell, M. Some Strategy Implications of a Matrix Approach to the Classification of Marketing Goods and Services. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 1986, 14(1), 13-20. Bell, M. A Matrix Approach to the Classification of Marketing of Goods and Services. J. Donnelly & W. George (Eds.), Marketing of Services, Chicago: American Marketing Association, 1981, 208-212. [19] [20] Chase, R. A Matrix for Linking Marketing and Production Variables in Service System Design. B. Hartman and J. Ringuest (Eds.), 1985 Proceedings of the American Institute for Decision Sciences, 739-742. Fitzsimmons, J., and Sullivan, R. Service Operations Management. New York : McGraw-Hill, 1982. Foxall, G. Marketing in the Service Industries. Totowa, N.J.: Frank Cass and Company, 1985. Hayes, R. and Wheelwright, S. Link Manufacturing Process and Product Life Cycles. Harvard Business Review, 1979, 57(1), 133-140. Hsieh, C. and Chu, T. Classification of Service Businesses from a Utility Creation Perspective. Service Industries Journal, 1992, 12(4), 545-557. Kotler, P. and Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1980. Levitt, T. Production-line Approach to Service. Harvard Business Review, 1972, 50(5), 41-52. Lovelock, C. Services Marketing: Text, Cases and Readings. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1984. Lovelock, C. Classifying Services to Gain Strategic Marketing Insight. Journal of Marketing, 1983, 47(3), 9-20. Mills, P. and Marguiles, N. Towards a Core Typology of Service Organizations. Academy of Management Review, 1980, 5(2), 255-265. Murdick, R., Render, B., and Russell, R. Service Operations Management. Needham Heights, Massachusetts: Allyn and Bacon, 1990. New York Times. Computer allows Levi's to offer made-to-order jeans. 1994, November 8: D10. Peters, T. Thriving on Chaos: Handbook for Management Revolution. New York: Knoph, 1987. Rathmell, J. What is Meant by Services. Journal of Marketing, 1966, 30(4), 32-36. Sasser, W., Olsen, R., and Wyckoff, D. Management of Service Operations: Text, Cases and Readings. Boston: Allen and Bacon, 1978. Schmenner, R. How can Service Businesses Survive and Prosper? Sloan Management Review, 1986, 27(3), 21-33. Shostack, G. Breaking Free from Product Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 1977, 41(4), 73-80. Stiff, R. and Pollack, J. Consumerism in the Service Sector. L. Berry, G. Shostak, and G. Upah (Eds.), Emerging Perspectives on Services Marketing, Chicago: American Marketing Association, 1983, 54-48.