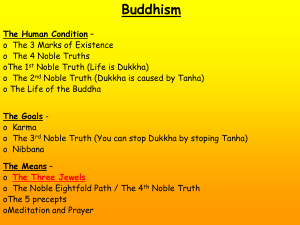

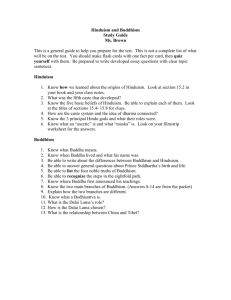

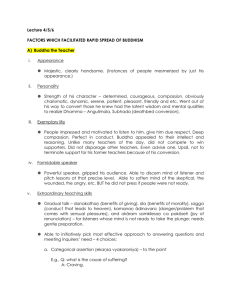

Buddhism in a Nutshell

advertisement