Death is the only certainty in life. End of Life Care in the Emergency

advertisement

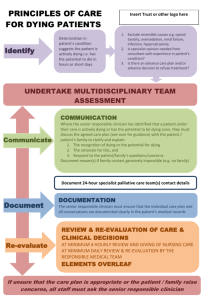

Death is the only certainty in life. End of Life Care in the Emergency Department is a recently coined phrase, but the concept predates all of those in this room. And most people who contemplate the end of their own life fear certain aspects of it - particularly the risk of pain, or indignity. Whereas it was common up to 50 years ago for people in this country to die at home, it is increasingly uncommon. 48% of of deaths occur in acute hospitals, 20% in long term care facilities, 25% at home and only 4% in hospice care. When expected, arrangements may be in place to deal with the concerns of the dying person, and their relatives. When unexpected, or precipitate, such plans may may be thwarted, or simply not yet in place. Interestingly, surveys have shown that most medical doctors would opt to die at home, if at all feasible. An audit study from 4 years ago showed that 84% of patients dying in hospital had accessed the hospital via the Emergency Department, with 24% of the deaths being unexpected. End of Life Care in the Emergency Department is opportunistic, in that it depends on many factors coming together at the one time. It relies on the determination of the staff to ensure the best possible experience for their patients and the patient’s relatives or friends. For it does require determination to deliver quality care in what is perceived by many outsiders as a chaotic setting. Every dying person has physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs. And it is relatively uncommon for one person to be able to supply support for each and every one of these needs. Instead, a team effort is essential. But that team must be prepared and, like an elite squad, practiced at their task. What are the barriers to a “high quality” death in the Emergency Department? They include the physical setting; often overcrowded, noisy, and with high intensity lighting 24 hours a day. It is psychologically extremely difficult to be plucked from one’s bed at home, gasping for breath, and be brought by ambulance, careening through the streets with sirens blaring, to a noisy environment, where the bustle of life-saving measures applied to one person may interfere with the peace and quiet required by a dying woman contemplating her last few hours or minutes on this earth. There is an understandable difficulty ensuring caring time for a person known to be dying, whose life cannot be prolonged by any means within the power of nursing and medical staff. Whilst concerned for these people, the pressure of other patients’ needs can be very distracting, running the risk of a lonely death within a crowded room. And what of the tensions within a family, knowing their loved one has been injured in a traffic collision, or in a murderous assault, and who now lies sedated, ventilated and paralysed, unable to communicate their needs, and with no prospects for survival? All deaths in the Emergency Department, or within 24 hours of admission, must be reported to the Coroner, with a very high proportion having post-mortem autopsies, as they will not otherwise fulfill the legal requirements for death certification. This places a further tension on the relations between families and staff, which may lead to difficulties. What can be done to optimise End of Life Care in Emergency Departments? The first thing is to believe that it can be improved, to examine each element carefully and to deal with every deficiency in a constructive fashion. The environment of the Emergency Department is designed for large-volume patient care, in a physically-confined area. To reduce the inevitable noise, bustle and constant light, requires a separate area that can be used to support the patient and their family, during the process of dying, and after death. Very few Emergency Departments in this country have adequate physical facilities for death and bereavement, although these facilities are, in fact, cheaper to provide than acute clinical space. The necessary investment is small, relative to the overall departmental budget, but the potential good for the lives of those who have been bereaved is enormous. And the possibility remains that good bereavement care will lead to shorter, less intense, grief responses and lower levels of psychological ill-health afterwards, with an earlier return to productive life for those remaining. This quiet place must have auditory and visual separation from the main business of the Emergency Department, whilst close enough to the main clinical area to allow ready access, with staff able to move to-and-fro without difficulty. It must be decorated in calm and soothing colours and fabrics, whilst keeping in mind the infection control elements required in a clinical environment. Access to refreshments and to external communications for family is vital. Nowadays, this means ensuring adequate mobile phone signal strength, which can be a difficulty in areas with radiation protection built-in to the walls. Staff, whether medical, nursing, clinical or clerical support personnel, must all be trained in the ways they can support dying people and their families. This equally means they (the staff) must face their own inevitable death, at least in broad philosophical terms. Several departments, my own included, now run End of Life Care seminars for their staff, as a multi-disciplinary effort to enhance the response to dying patients and bereaved families. We also teach Breaking Bad news and End of Life Care to undergraduate medical students in Trinity College. There must be a willingness to engage with the physical, emotional and spiritual needs of patients, whatever the religious beliefs of the staff. This is increasingly important in an Ireland which, 50 years ago had mainly Roman Catholics and Protestant denominations, with a smattering of Jewish people, but which now has many other different religious groups, ranging from Muslim, thorough Animist, Buddhist, Coptic, Daoist, Eastern Orthodox, Hindu, Sikh and others. Unless the inevitability of death is recognised, there may be a reluctance to use adequate doses of powerful painkillers, despite clear evidence of need. However, access to adequate pain relief is a “must” for those who have pain. Once the decision is made, the the provision of relief can be complex, depending on the specific needs of the patient. Methods to enhance this include the use of technology, such as patient-controlled analgesic pumps, or trans-cutaneous pain relief, and the use of personnel, such as paincontrol, or palliative-care, specialists. The latter are rarely available on a 24-hour basis, but can provide tuition for those who are, such as medical and nursing staff in Emergency Departments, who can then use the technology as required. Furthermore, spiritual support can reduce significantly the expressed need for pain relief. This can be supplied by pastoral professionals or, to a certain extent, by appropriately prepared Emergency Department staff. All these issues might be dealt with better if there was a more open and structured approach to End-of-Life Care planning at personal and family level. If a person is discharged from hospital to home, with a known terminal illness, there seems to be a reluctance to engage with them and their family to understand the next step in the process. The process of dying is now unfamiliar to most Irish people, as death now occurs predominantly in healthcare facilities. Delirium in the final stages Is much more distressing for the observers than for the delirious, dying individual. This often leads to a panic situation when the patient eventually deteriorates and the family, or friends, lose control and dial the emergency number for the ambulance service. Once that behemoth is unleashed, the result is predictable - the patient will be brought to the nearest Emergency Department, usually in extremis. They will then die in the Emergency Department, or during the journey. In cases where the patient has already suffered a cardiac arrest, there is a natural reluctance on the part of pre-hospital emergency care providers (ambulance personnel) to pronounce death in the home, which leads to ongoing resuscitative efforts and pronouncement of death in the Emergency Department. Some of this is explained by a wish to spare the family the aftermath of dealing with the mortal remains in their home, a process now foreign to most people. That then leaves the Emergency Department team to deal with the process of informing relatives and dealing with their grief, and with the logistic difficulties of identification, and referral to the Coroner. Although the Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council has developed a Clinical Practice Guideline to reduce this problem, it is likely to remain an issue of concern into the medium-term future. An increasing concern for Emergency Medicine practitioners is the apparent reluctance to allow frail elderly men or women die peacefully in nursing homes. Hypostatic pneumonia, which leads to delirium and death over a period of a few days used be termed “the old man’s friend”. Once secretions were dealt with, the patient turned regularly to reduce discomfort and pain prevented by the use of “the Brompton Cocktail”, the patient would slip away quietly, with their relatives and friends by the bedside. This no longer occurs. A similar issue also affects demented elderly patients who fall in nursing homes, or who develop urinary tract infections and sepsis. Our perception of underlying cause is the risk of an adverse comment from the coroner, or worse still, from a HIQA investigation into increasing numbers of deaths in nursing homes. The fallout from Lees Cross has had both positive and negative effects in this regard, in my view. What can the Oireachtas Committee do? Probably simply encourage Health Policy that supports good End of Life Care, including early bereavement care, within Emergency Departments. Ensuring that it is firmly on the agenda for healthcare planning is critical to developing a response from planners, managers and clinicians that will lead to a greater, more positive, societal impact. It behoves us all to consider how and where we would wish to die and to plan for “a good death”, on a personal basis. Once such a plan is devised, it should be shared with others, such as the next of kin and the family doctor, with clarity achieved on the wishes of the person involved. Using the “Think Ahead” template developed by the Forum on the End of Life and supported by the Irish Hospice Foundation is a readily accessible way to deal with this issue. It is important to ensure access to this personal plan on a 24/7 basis, ideally in a central on-line register, to ensure that appropriate levels of care and comfort can be provided, consistent with the wishes of the patient and their current clinical status. Ideally, every competent person entering a nursing home for long-term, end-of -life care, should be provided with encouragement and support to fill in this template. The Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Bill 2013 may have a role to play in ensuring that the loss of ability to communicate, or to make further decisions, does not lead to a situation where an incapacitated person’s wishes are nullified by external pressures, or by uncertainty as to their desires. A peaceful, timely death at home, or in a nursing home, should be seen as the norm, rather than an aberration and a failure of the health care system. Death in hospital, particularly the Emergency Department will remain an everyday reality, but careful planning, sensible use of existing resources and the provision of low-cost, lowtech environmental improvements should make it a much more acceptable process for those dying and for their families. Death in th eEmergency Department can be made peaceful. It only needs willing hearts.