Welcome to Advanced Placement Language and Composition

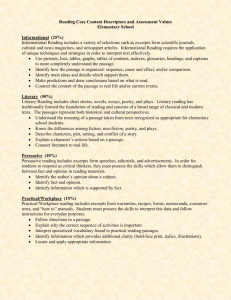

advertisement

Advanced Placement Language and Composition Summer Reading Packet 2010 Welcome to Advanced Placement Language and Composition! Next year, we will be studying together with a dual purpose: to prepare you for the AP Language and Composition test by your learning and applying rhetorical devices and to expose you to the American literary tradition. Luckily, these purposes dovetail nicely together, but we must all be prepared to work hard every day. In order to begin our journey together, you will be required to complete summer readings and assignments tied into those readings. The books you will be reading will meet both of our purposes: one book is a classic piece of American fiction; the other will be a work of nonfiction of your choice from a list of options. Remember, AP Language is a college level class. Therefore, we are setting our expectations of you high, and we know that you can reach them! However, you will need to spend time and effort when reading these books. Reading them quickly “just to get it done,” or worse, reading only Sparknotes or watching film version of your books will not suffice! You will need to read these texts closely, and you will need to be looking for not only what the author says, but also how he/she says it. WE WILL BE COMING BACK TO THESE BOOKS OVER AND OVER THROUGHOUT THE YEAR! Therefore, it is not required, but we highly suggest that you purchase a copy of each of your books. You can get them at a local bookstore or even buy them used on-line. You can borrow the books from the high school or public library if you do not want to purchase them. Within this packet, you will find the two reading assignments and an annotated list of nonfiction books. You will also find some information we want you to be aware of as you are reading—things like close reading strategies and how to mark up a book. We strongly encourage you to read the articles that are enclosed; there is a ton of useful information in them to help you be a close, observant reader—a skill that is critical for this year and after! There will also be instructions for completing the assignments for each of the two books you will read. After school is out for this year and we have had time to catch our breath, we will be posting all of this information on our websites and also updated instructions when necessary. We will also try to start a blog for the American novel to pose some questions and to answer questions you may have. The information will be uploaded to our websites after June 24. We are very excited to create and teach this new course, which we believe will offer you a new way of looking at the things that you read, whether they are pieces of fiction, nonfiction, or even visual texts. As we have already said, we will all be working diligently all year, but we truly feel you will be stronger readers, writers, and thinkers at the end of our time together. Happy summer! Happy reading! Mrs. O’Brien and Mrs. Brown Next year in AP Language, you will be exploring several types of writing. Specifically for the AP Test, you will need to be able to write the following types of essays: 1. Analysis—a close examination of texts, with the awareness of a writer’s purpose and the techniques the writer used to achieve it 2. Argument—a discourse intended to persuade an audience through reasons and/or evidence 3. Synthesis—a bringing together of several texts, both written and visual, to form a coherent essay For the purpose of summer reading, you will focus on analysis of the texts that you are reading. This will require you to read closely and carefully. Yes, you need to read for literal meaning (obviously, you must understand what is going on in the text), but you will also need to read “between the lines.” To analyze is to break a complicated item into its component parts, examine those parts individually, and explain how they work together to create the larger, more complex entity you are studying. Assignment #1: Read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain While we will be expanding your analysis skills next year, for now, we will ask you to analyze the book using some literary elements with which you are used to working. Feel free to “note” any literary elements that you find while reading the novel. However, for the purpose of the essay that you will be writing upon your return to school, you will want to focus your analysis on the elements listed below. The questions are simply to guide your thinking; you should not think that these questions are all-encompassing. Characterization o Who are the characters in the book, and what purpose do they serve? o How does Twain develop the characters? o What do you notice about the way the characters are described? o How does the way the characters speak (i.e. dialect) reveal who they are and their place in their society? o What do the particular characters do to help develop the plot and the theme(s)? Setting o What is the setting (time and place) where the novel takes place? o What do you notice about how the setting is described? o What is the significance of the setting? o How does the setting help to develop the theme(s)? Theme(s) o What are the themes present in the novel? o What theme(s) is/are most important? Why/How? o How does Twain develop the theme(s)? o How do the characterization and setting link to the theme(s)? While reading, complete at least thirty (30) Double Entry Journal (DEJ) entries. Your entries should be a balance of the three literary elements listed above. Of course, you may have more than the minimal number of entries; you may want to include entries that address questions you have, clarifications of things in the text, quotes that you love, etc. (See the attached Double Entry Journal explanation and template. You do not have to use the attached template; it is there for your use or reference. Your DEJ will be graded for completeness, but you will want to make it as thorough and thoughtful as possible. Your DEJ is due the first day of school. Upon our return to school, you will be writing an analysis essay of Huck Finn in class, using your DEJ to support your analysis. Thus, the better your journal entries are, the easier your essay will be to write. ALL DOUBLE ENTRY JOURNAL ENTRIES MUST BE HAND-WRITTEN! Typed journal entries will not be accepted for credit. In this packet is a resource about “squeezing the text,” which gives some insights for closely reading a text. Assignment #2: Choose and read one of the nonfiction selections on the attached annotated list. You need to make sure that you do a close and careful reading. You cannot just read “to get it done.” For this assignment, we are asking you to annotate your book. If you own your book, you can annotate by highlighting and annotating (making notes in) the margins of the text. If you are choosing not to buy your book, you can still annotate the book by making notes on “stickies” and placing them on the pages of the book to which they apply. See the “How to Mark a Book” resource in this packet for more information on how to annotate your book. Upon our return to school, you will create an electronic “book talk,” using a technology platform, to share your book with your classmates. You will be trained on the technology upon your return to school. You will want to annotate your book for items that will help you entice a “would-be” reader to want to read your book. Some things you may want to look for as you read: o Parts that will help you give a brief overview of your book. o Information on the author. o Quotes that you like or that help you make a point. o Parts that help show the writer’s style. Here are some other things to think about and note as your read: o Listen to the questions and observations your mind makes as you read and capture those mind-noises in the book. o Some things to note in your book might be places in the text where you: are confused, puzzled, or surprised struck by the language or an image can relate the text to something in your life or to another text or to something happening locally or globally can predict what might happen react strongly o You may want to use one or more of these to help you create your notes: a paraphrase of a complex segment of text possible explanation of a confusing material a main idea from the resource and why it is important a strong positive or negative reaction and an explanation of that reaction a reason for agreeing or disagreeing with the author/producer a comparison and/or contrast of a passage with another resource or with prior knowledge a prediction based on evidence from the resource a question generated as a result of reading a description of a personal experience that relates to the resource AP Language and Composition Nonfiction Reading Choices 2010-2011 Ambrose, Stephen. Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. In this sweeping adventure story, Stephen E. Ambrose, the bestselling author of D-Day, presents the definitive account of one of the most momentous journeys in American history. Ambrose follows the Lewis and Clark Expedition from Thomas Jefferson's hope of finding a waterway to the Pacific, through the heart-stopping moments of the actual trip, to Lewis's lonely demise on the Natchez Trace. Along the way, Ambrose shows us the American West as Lewis saw it—wild, awesome, and pristinely beautiful. Undaunted Courage is a stunningly told action tale that will delight readers for generations. (Borders) Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. In 1918, a plague swept across the world virtually without warning, killing healthy young adults as well as vulnerable infants and the elderly. Hospitals and morgues were quickly overwhelmed; in Philadelphia, 4,597 people died in one week alone and bodies piled up on the streets to be carted off to mass graves. But this was not the dreaded Black Death-it was "only influenza." In this sweeping history, Barry (Rising Tide) explores how the deadly confluence of biology (a swiftly mutating flu virus that can pass between animals and humans) and politics (President Wilson's all-out war effort in WWI) created conditions in which the virus thrived, killing more than 50 million worldwide and perhaps as many as 100 million in just a year. Overcrowded military camps and wide-ranging troop deployments allowed the highly contagious flu to spread quickly; transport ships became "floating caskets." Yet the U.S. government refused to shift priorities away from the war and, in effect, ignored the crisis. Shortages of doctors and nurses hurt military and civilian populations alike, and the ineptitude of public health officials exacerbated the death toll. In Philadelphia, the hardest-hit municipality in the U.S., "the entire city government had done nothing" to either contain the disease or assist afflicted families. Instead, official lies and misinformation, Barry argues, created a climate of "fear... [that] threatened to break the society apart." Barry captures the sense of panic and despair that overwhelmed stricken communities and hits hard at those who failed to use their power to protect the public good. He also describes the work of the dedicated researchers who rushed to find the cause of the disease and create vaccines. Flu shots are widely available today because of their heroic efforts, yet we remain vulnerable to a virus that can mutate to a deadly strain without warning. Society's ability to survive another devastating flu pandemic, Barry argues, is as much a political question as a medical one. (Publisher’s Weekly) Beavan, Colin. No Impact Man: The Adventures of a Guilty Liberal Who Attempts to Save the Planet and the Discoveries He Makes about Himself and Our Way of Life in the Process. Beavan chronicles his yearlong effort to leave as little impact on the environment as possible. Realizing that he had erred in thinking that condemning other people's misdeeds somehow made [him] virtuous, he makes a stab at genuine (and radical) virtue: forgoing toilet paper and electricity, relinquishing motorized transportation, becoming a locavore and volunteering with environmental organizations. Beavan captures his own shortcomings with candor and wit and offers surprising revelations: lower resource use won't fill the empty spaces in my life, but it is just possible that a world in which we already suffer so much loss could be made a little bit better if husbands were kinder to their wives. While few readers will be tempted to go to Beavan's extremes, most will mull over his thought-provoking reflections and hopefully reconsider their own lifestyles. (Publishers Weekly) Bradley, James. Flags of Our Fathers. In this unforgettable chronicle of perhaps the most famous moment in American military history, James Bradley has captured the glory, the triumph, the heartbreak, and the legacy of the six men who raised the flag at Iwo Jima. Here is the true story behind the immortal photograph that has come to symbolize the courage and indomitable will of America. In February 1945, American Marines plunged into the surf at Iwo Jima--and into history. Through a hail of machine-gun and mortar fire that left the beaches strewn with comrades, they battled to the island's highest peak. And after climbing through a landscape of hell itself, they raised a flag. Now the son of one of the flag raisers has written a powerful account of six very different men who came together in a moment that will live forever. (Bookrags) Bradley, James. Flyboys. In this book Bradley writes of the Pacific and World War II. Over the island of Chichi Jima, nine American flyboys—Navy and Marine airmen sent to bomb the Japanese—were shot down. One would be miraculously rescued, but the others would be imprisoned and subjected to a fate so terrible that it has been kept top secret until now. Flyboys reveals for the first time what happened to these men. Bradley details the war in the Pacific, from the attack on Pearl Harbor through the bitter end, including some of the most savage fighting the world has ever seen. And he explores the Japanese warrior culture and how America’s own ideas about war in peace conflicted with Japan’s. This is not just the story of those who died, but also of those who lived—including the young Navy pilot who would one day become the president of the United States. (Amazon) Bryson, Bill. A Walk in the Woods. In the grand tradition of the travel memoir, writer Bill Bryson tells the story of his trek through the wilderness along the Appalachian Trail. With no real outdoors experience or knowledge of the trail's difficulty, he walks into a sporting goods store in his hometown of Hanover, New Hampshire, and spends a small fortune on the necessary gear, most of which is a mystery to him. His plan is to hike the entire 2,200-mile trail in one season, starting at Springer Mountain in Georgia and ending at Mt. Katahdin in Maine. He has a companion who is as comically unprepared for the trek as he is. Stephen Katz is an old school friend, who climbs off the plane with a large stomach and a duffel bag of Snickers. This hilarious book intertwines a history of the Appalachian Trail, its hikers, and the American wilderness with Bryson’s personal challenge to not give up his trek, even though he has every reason to do so (Amazon). Capote, Truman. In Cold Blood. On November 15, 1959, in the small town of Holcomb, Kansas, four members of the Clutter family were savagely murdered by blasts from a shotgun held a few inches from their faces. There was no apparent motive for the crime, and there were almost no clues. Five years, four months and twenty-nine days later, on April 14, 1965, Richard Eugene Hickock, aged thirty-three, and Perry Edward Smith, aged thirty-six, were hanged for the crime on a gallows in a warehouse in the Kansas State Penitentiary in Lansing, Kansas. In Cold Blood is the story of the lives and deaths of these six people. It has already been hailed as a masterpiece.(Borders) Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. First published by Houghton Mifflin in 1962, Silent Spring alerted a large audience to the environmental and human dangers of indiscriminate use of pesticides, spurring revolutionary changes in the laws affecting our air, land, and water. "Silent Spring became a runaway bestseller, with international reverberations . . . [It is] well crafted, fearless and succinct . . . Even if she had not inspired a generation of activists, Carson would prevail as one of the greatest nature writers in American letters" (Peter Matthiessen, for Time's 100 Most Influential People of the Century). (Borders) Dawidoff, Nicholas. The Catcher was a Spy: The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg. The story of Moe Berg, sometime major-league catcher, sometime spy, sometime lawyer, and full-time enigma. Berg, a Princeton graduate and Wall Street lawyer who played sporadically (and not very well) with the major leagues between 1923 and 1939, was recruited by Wild Bill Donovan for the OSS during World War II, and he eventually was awarded the Medal of Freedom for his work in Germany collecting information for the H-bomb project. A Jew, Berg was the odd man out in nearly every world he inhabited--the Ivy League, baseball, Wall Street, the OSS--and Dawidoff neatly emphasizes how his sense of himself as an outsider worked marvelously to his advantage in espionage, just as it had inhibited and held him back everywhere else. (Biblio.com) Eagon, Timothy. The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dustbowl. The dust storms that terrorized the High Plains in the darkest years of the Depression were like nothing ever seen before or since. Timothy Egan's critically acclaimed account rescues this iconic chapter of American history from the shadows in a tour de force of historical reportage. Following a dozen families and their communities through the rise and fall of the region, Egan tells of their desperate attempts to carry on through blinding black dust blizzards, crop failure, and the death of loved ones. Brilliantly capturing the terrifying drama of catastrophe, Egan does equal justice to the human characters who become his heroes, "the stoic, long-suffering men and women whose lives he opens up with urgency and respect" (New York Times). (Borders) Ellis, Joseph J. American Creation. This subtle, brilliant examination of the period between the War of Independence and the Louisiana Purchase puts Pulitzer-winner Ellis (Founding Brothers) among the finest of America's narrative historians. Six stories, each centering on a significant creative achievement or failure, combine to portray often flawed men and their efforts to lay the republic's foundation. Set against the extraordinary establishment of the most liberal nation-state in the history of Western Civilization... in the most extensive and richly endowed plot of ground on the planet are the terrible costs of victory, including the perpetuation of slavery and the cruel oppression of Native Americans. Ellis blames the founders' failures on their decision to opt for an evolutionary revolution, not a risky severance with tradition (as would happen, murderously, in France, which necessitated compromises, like retaining slavery). Despite the injustices and brutalities that resulted, Ellis argues, this deferral strategy was a profound insight rooted in a realistic appraisal of how enduring social change best happens. (Publishers Weekly) Ellis, Joseph J. Founding Brothers. In retrospect, it seems as if the American Revolution was inevitable. But was it? In Founding Brothers, Ellis reveals that many of those truths we hold to be self-evident were actually fiercely contested in the early days of the republic. Ellis focuses on six crucial moments in the life of the new nation, including a secret dinner at which the seat of the nation's capital was determined--in exchange for support of Hamilton's financial plan; Washington's precedent-setting Farewell Address; and the Hamilton and Burr duel. Most interesting, perhaps, is the debate (still dividing scholars today) over the meaning of the Revolution. In a fascinating chapter on the renewed friendship between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson at the end of their lives, Ellis points out the fundamental differences between the Republicans, who saw the Revolution as a liberating act and hold the Declaration of Independence most sacred, and the Federalists, who saw the revolution as a step in the building of American nationhood and hold the Constitution most dear. Throughout the text, Ellis explains the personal, face-to-face nature of early American politics--and notes that the members of the revolutionary generation were conscious of the fact that they were establishing precedents on which future generations would rely. (Publishers Weekly) Gawande, Atul. Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science. Medicine reveals itself as a fascinatingly complex and "fundamentally human endeavor" in this distinguished debut essay collection by a surgical resident and staff writer for the New Yorker. Gawande, a former Rhodes scholar and Harvard Medical School graduate, illuminates "the moments in which medicine actually happens," and describes his profession as an "enterprise of constantly changing knowledge, uncertain information, fallible individuals, and at the same time lives on the line." Gawande's background in philosophy and ethics is evident throughout these pieces, which range from edgy accounts of medical traumas to sobering analyses of doctors' anxieties and burnout. With humor, sensitivity and critical intelligence, he explores the pros and cons of new technologies, including a controversial factory model for routine surgeries that delivers superior success rates while dramatically cutting costs. He also describes treatment of such challenging conditions as morbid obesity, chronic pain and necrotizing fasciitis the often-fatal condition caused by dreaded "flesh-eating bacteria" and probes the agonizing process by which physicians balance knowledge and intuition to make seemingly impossible decisions. What draws practitioners to this challenging profession, he concludes, is the promise of "the alterable moment the fragile but crystalline opportunity for one's know-how, ability or just gut instinct to change the course of another's life for the better." These exquisitely crafted essays, in which medical subjects segue into explorations of much larger themes, place Gawande among the best in the field. (Publishers Weekly) Gladwell, Malcolm. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference The New Yorker writer Malcolm Gladwell looks at why major changes in our society so often happen suddenly and unexpectedly. Ideas, behavior, messages, and products, he argues, often spread like outbreaks of infectious disease. Just as a single sick person can start an epidemic of the flu, so too can a few fare-beaters and graffiti artists fuel a subway crime wave, or a satisfied customer fill the empty tables of a new restaurant. These are social epidemics, and the moment they take off, they reach their critical mass, or, the Tipping Point. Gladwell introduces us to the particular personality types who are natural pollinators of new ideas and trends, the people who create the phenomenon of word of mouth, and he analyzes fashion trends, smoking, children's television, direct mail, and the early days of the American Revolution for clues about making ideas infectious. He also visits a religious commune, a successful high-tech company, and one of the world's greatest salesmen to show how to start and sustain social epidemics. (Borders) Gladwell, Malcom. Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking Blink is about the first two seconds of looking—the decisive glance that knows in an instant. Gladwell, the best-selling author of The Tipping Point, campaigns for snap judgments and mind reading with a gift for translating research into splendid storytelling. Building his case with scenes from a marriage, heart attack triage, speed dating, choking on the golf course, selling cars, and military maneuvers, he persuades readers to think small and focus on the meaning of "thin slices" of behavior. The key is to rely on our "adaptive unconscious"—a 24/7 mental valet—that provides us with instant and sophisticated information to warn of danger, read a stranger, or react to a new idea. Gladwell includes caveats about leaping to conclusions: marketers can manipulate our first impressions, high arousal moments make us "mind blind," focusing on the wrong cue leaves us vulnerable to "the Warren Harding Effect" (i.e., voting for a handsome but hapless president). In a provocative chapter that exposes the "dark side of blink," he illuminates the failure of rapid cognition in the tragic stakeout and murder of Amadou Diallo in the Bronx. He underlines studies about autism, facial reading and cardio uptick to urge training that enhances high-stakes decision-making. In this brilliant, cage-rattling book, one can only wish for a thicker slice of Gladwell's ideas about what Blink Camp might look like.--Barbara Mackoff (Borders) Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. The life and times of Abraham Lincoln have been analyzed and dissected in countless books. Do we need another Lincoln biography? In Team of Rivals, esteemed historian Doris Kearns Goodwin proves that we do. Though she can't help but cover some familiar territory, her perspective is focused enough to offer fresh insights into Lincoln's leadership style and his deep understanding of human behavior and motivation. Goodwin makes the case for Lincoln's political genius by examining his relationships with three men he selected for his cabinet, all of whom were opponents for the Republican nomination in 1860: William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase, and Edward Bates. These men, all accomplished, nationally known, and presidential, originally disdained Lincoln for his backwoods upbringing and lack of experience, and were shocked and humiliated at losing to this relatively obscure Illinois lawyer. Yet Lincoln not only convinced them to join his administration--Seward as secretary of state, Chase as secretary of the treasury, and Bates as attorney general--he ultimately gained their admiration and respect as well. How he soothed egos, turned rivals into allies, and dealt with many challenges to his leadership, all for the sake of the greater good, is largely what Goodwin's fine book is about. Had he not possessed the wisdom and confidence to select and work with the best people, she argues, he could not have led the nation through one of its darkest periods. Ten years in the making, this engaging work reveals why "Lincoln's road to success was longer, more tortuous, and far less likely" than the other men, and why, when opportunity beckoned, Lincoln was "the best prepared to answer the call." This multiple biography further provides valuable background and insights into the contributions and talents of Seward, Chase, and Bates. Lincoln may have been "the indispensable ingredient of the Civil War," but these three men were invaluable to Lincoln and they played key roles in keeping the nation intact. --Shawn Carkonen (Amazon) Hickman, Homer Jr. Rocket Boys (also published as October Sky). In 1957, when 14-year-old Homer Hickman, a.k.a. Sonny, watches Sputnik fly over his hometown of Coalwood, West Virginia, his life is changed forever. Knowing he wants to be part of the space race, Sonny and his friends, set out to learn as much as they can about launching rockets. Soon, these Rocket Boys wind up enlisting the help of everyone in town. Set against a backdrop of miners' strikes, the beginning of the Cold War, and America's loss of innocence, this book reads like a novel. (Borders) Hillenbrand, Laura. Seabiscuit: An American Legend. The book takes place between 1929 and 1940, a period during which the world changed dramatically. In the United States, a stock market crash heralded the decade-long Great Depression that mired the country in despair and hopelessness. During those dark days, average citizens clung to even the smallest diversion that afforded hope or escape from their daily lives. An unlikely hero—a short, squat, and seemingly unfit racehorse—offered one such distraction, becoming a media darling and capturing the national imagination. In fact, in 1938, as the world teetered on the brink of World War II, the majority of new coverage was devoted not to politicians or warmongers but to one knobby-kneed horse nearly past his prime. Seabiscuit became a cultural icon, according to Hillenbrand, and offered hope to a generation of disadvantaged people: if he could overcome adversity and become a winner, so could they. From his initial outings in the dust of Tijuana to his grudge match with Triple Crown winner War Admiral, Seabiscuit epitomized the rags-to-riches American dream for millions of impoverished citizens who wondered whether the dream was still possible. (Amazon) Krakauer, Jon. Into the Wild. After graduating from Emory University in Atlanta in 1992, top student and athlete Christopher McCandless abandoned his possessions, gave his entire $24,000 savings account to charity and hitchhiked to Alaska, where he went to live in the wilderness. Four months later, he turned up dead. His diary, letters and two notes found at a remote campsite tell of his desperate effort to survive, apparently stranded by an injury and slowly starving. They also reflect the posturing of a confused young man, raised in affluent Annandale, Va., who selfconsciously adopted a Tolstoyan renunciation of wealth and return to nature. Krakauer, a contributing editor to Outside and Men's Journal, retraces McCandless's ill-fated antagonism toward his father, Walt, an eminent aerospace engineer. Krakauer also draws parallels to his own reckless youthful exploit in 1977 when he climbed Devils Thumb, a mountain on the AlaskaBritish Columbia border, partly as a symbolic act of rebellion against his autocratic father. In a moving narrative, Krakauer probes the mystery of McCandless's death, which he attributes to logistical blunders and to accidental poisoning from eating toxic seed pods. (From Publishers Weekly) (Amazon) Krakauer, Jon. Into Thin Air: A Personal Account of the Mt. Everest Disaster. This gripping true-life adventure tale tells the story of the disaster in which several climbers died on the slopes of Mt. Everest in 1996, as witnessed by Jon Krakauer, a journalist who is also one of the climbers to reach the summit that year. Led by Rob Hall, one of the most highly respected climbers in the world at that time, the team Krakauer climbs with becomes split up after a series of small incidents and a sudden change in the weather, leaving five of his teammates dead on the mountain. Another expedition led by the flamboyant Scott Fischer also loses climbers in the storm, including Fischer himself. Krakauer recounts the events of the ill-fated expeditions from his own personal experience and makes several suggestions as to what may have led to the climbers being caught high on. the world’s most sought-after “trophy summit.” Kurlansky, Mark. Salt: A World History. Salt, the only rock we eat, has made a glittering, often surprising contribution to the history of humankind. Until about a hundred years ago, when modern geology revealed its prevalence, salt was one of the world’s most sought-after commodities. A substance so valuable it served as currency, salt has influenced the establishment of trade routes and cities, provoked and financed wars, secured empires and inspired revolutions. Populated by colorful characters and filled with fascinating details, Mark Kurlansky’s kaleidoscopic and illuminating history is a multi-layered masterpiece that blends economic, scientific, political, religious, and culinary records into a rich and memorable tale. Larson, Eric. The Devil and the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America Bringing Chicago circa 1893 to vivid life, Erik Larson's spellbinding bestseller intertwines the true tale of two men -- the brilliant architect behind the legendary 1893 World's Fair, striving to secure America's place in the world; and the cunning serial killer who used the fair to lure his victims to their death. Combining meticulous research with nail-biting storytelling, Erik Larson has crafted a narrative with all the wonder of newly discovered history and the thrills of the best fiction. (Borders) Levitt, Steve D. Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything. Through forceful storytelling and wry insight, Levitt and Dubner show that economics is, at root, the study of incentives—how people get what they want, or need, especially when other people want or need the same thing. In Freakonomics, they explore the hidden side of . . . well, everything. The inner workings of a crack gang. The truth about real-estate agents. The myths of campaign finance. The telltale marks of a cheating schoolteacher. The secrets of the Klu Klux Klan. What unites all these stories is a belief that the modern world, despite a great deal of complexity and downright deceit, is not impenetrable, is not unknowable, and—if the right questions are asked—is even more intriguing than we think. All it takes is a new way of looking. Freakonomics establishes this unconventional premise: If morality represents how we would like the world to work, then economics represents how it actually does work. It is true that readers of this book will be armed with enough riddles and stories to last a thousand cocktail parties. But Freakonomics can provide more than that. It will literally redefine the way we view the modern world. (Borders) M cCollough, David. 1776. In this stirring book, David McCullough tells the intensely human story of those who marched with General George Washington in the year of the Declaration of Independence—when the whole American cause was riding on their success, without which all hope for independence would have been dashed and the noble ideals of the Declaration would have amounted to little more than words on paper. Based on extensive research in both American and British archives, 1776 is a powerful drama written with extraordinary narrative vitality. It is the story of Americans in the ranks, men of every shape, size, and color, farmers, schoolteachers, shoemakers, no-accounts, and mere boys turned soldiers. And it is the story of the King's men, the British commander, William Howe, and his highly disciplined redcoats who looked on their rebel foes with contempt and fought with a valor too little known. (Borders) Mortenson, Greg, and David Oliver Relin. Three Cups of Tea: One Man’s Mission to Promote Peace…One School at a Time. The astonishing, uplifting story of a real-life Indiana Jones and his humanitarian campaign to use education to combat terrorism in the Taliban’s backyard. Anyone who despairs of the individual’s power to change lives has to read the story of Greg Mortenson, a homeless mountaineer who, following a 1993 climb of Pakistan’s treacherous K2, was inspired by a chance encounter with impoverished mountain villagers and promised to build them a school. Over the next decade he built fifty-five schools especially for girls that offer a balanced education in one of the most isolated and dangerous regions on earth. As it chronicles Mortenson’s quest, which has brought him into conflict with both enraged Islamists and uncomprehending Americans, "Three Cups of Tea" combines adventure with a celebration of the humanitarian spirit. (Borders) Mortenson, Greg. Stones to Schools: Promoting Peace with Books, Not Bombs, in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In this dramatic first-person narrative, Greg Mortenson picks up where Three Cups of Tea left off in 2003, recounting his relentless, ongoing efforts to establish schools for girls in Afghanistan; his extensive work in Azad Kashmir and Pakistan after a massive earthquake hit the region in 2005; and the unique ways he has built relationships with Islamic clerics, militia commanders, and tribal leaders even as he was dodging shootouts with feuding Afghan warlords and surviving an eight-day armed abduction by the Taliban. He shares for the first time his broader vision to promote peace through education and literacy, as well as touching on military matters, Islam, and women - all woven together with the many rich personal stories of the people who have been involved in this remarkable two-decade humanitarian effort. (Bookbrowse) Navasky, Victor S. Naming Names. This book, written by a professor at Columbia University, is about the witchhunt for Communist—imagined to be lurking in every corner—during the age of Senator Joe McCarthy. It seems Hollywood insiders were particularly targeted and coerced into turning in friends and family for real or imagined Communist associations. The book focuses heavily on a few people who caved in and named names, a few others who stood strong, and how both sides lived afterwards with their choices. Philbrick, Nathaniel. In the Heart of the Sea. In the Heart of the Sea tells perhaps the greatest sea story ever. Philbrick interweaves his account of this extraordinary ordeal of ordinary men with a wealth of whale lore and with a brilliantly detailed portrait of the lost, unique community of Nantucket whalers. Impeccably researched and beautifully told, the book delivers the ultimate portrait of man against nature, drawing on a remarkable range of archival and modern sources, including a long-lost account by the ship's cabin boy. At once a literary companion and a pageturner that speaks to the same issues of class, race, and man's relationship to nature that permeate the works of Melville, In the Heart of the Sea will endure as a vital work of American history.(Borders) Philbrick, Nathaniel. Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community and War. Nathaniel Philbrick became an internationally renowned author with his National Book Award winning In the Heart of the Sea, hailed as spellbinding by Time Magazine. In Mayflower, Philbrick casts his spell once again, giving us a fresh and extraordinarily vivid account of our most sacred national myth: the voyage of the Mayflower and the settlement of Plymouth Colony. From the Mayflower’s arduous Atlantic crossing to the eruption of King Philips War between colonists and natives decades later, Philbrick reveals in this electrifying history of the Pilgrims a fifty-fiveyear epic, at once tragic and heroic, that still resonates with us today. (Borders) Roberts, Cokie. Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised Our Nation. While much has been written about the men who signed the Declaration of Independence, battled the British, and framed the Constitution, the wives, mothers, sisters and daughters they left behind have been little noticed by history. #1 New York Times bestselling author Cokie Roberts brings us women who fought the Revolution as valiantly as the men, often defending their very doorsteps. Drawing upon personal correspondence, private journals, and even favored recipes, Roberts reveals the often surprising stories of these fascinating women, bringing to life the everyday trials and extraordinary triumphs of individuals like Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, Deborah Read Franklin, Eliza Pinckney, Catherine Littlefield Green, Esther DeBerdt Reed and Martha Washington-proving that without our exemplary women, the new country might have never survived. (Borders) Wolfe, Tom. The Right Stuff. After an opening chapter on the terror of being a test pilot's wife, the story cuts back to the late 1940s, when Americans were first attempting to break the sound barrier. Test pilots, we discover, are people who live fast lives with dangerous machines, not all of them airborne. Chuck Yeager was certainly among the fastest, and his determination to push through Mach 1--a feat that some had predicted would cause the destruction of any aircraft— makes him the book's guiding spirit. Yet soon the focus shifts to the seven initial astronauts. Wolfe traces Alan Shepard's suborbital flight and Gus Grissom's embarrassing panic on the high seas (making the controversial claim that Grissom flooded his Liberty capsule by blowing the escape hatch too soon). The author also produces an admiring portrait of John Glenn's apple-pie heroism and selfless dedication. By the time Wolfe concludes with a return to Yeager and his late-career exploits, the narrative's epic proportions and literary merits are secure. Certainly The Right Stuff is the best, the funniest, and the most vivid book ever written about America's manned space program. (Amazon) Zakaria, Fareed. The Post American World. "This is not a book about the decline of America, but rather about the rise of everyone else." So begins Fareed Zakaria's important new work on the era we are now entering. Following on the success of his best-selling The Future of Freedom, Zakaria describes with equal prescience a world in which the United States will no longer dominate the global economy, orchestrate geopolitics, or overwhelm cultures. He sees the "rise of the rest"—the growth of countries like China, India, Brazil, Russia, and many others—as the great story of our time, and one that will reshape the world. The tallest buildings, biggest dams, largest-selling movies, and most advanced cell phones are all being built outside the United States. This economic growth is producing political confidence, national pride, and potentially international problems. How should the United States understand and thrive in this rapidly changing international climate? What does it mean to live in a truly global era? Zakaria answers these questions with his customary lucidity, insight, and imagination. (Amazon) Double-Entry Journal Double entry reading journals allow you “to put [your] fingerprints all over the text.” You must do more than glide over the text, decoding with ease, but making only limited amounts of meaning. You must handle the text, take it apart, manipulate it, look for its heart, find out what makes it tick, chunk it into meaningful bits and then interrogate each bit. Double entry journals are ways to help you read with an investigating eye. It helps you to slow down and pay attention when you read. Double entry journals teach you the critical art of close reading. To construct knowledge, we have to actively interact with and manipulate the raw materials, facts. A double entry reading journal is one way to interact with what we read, increase critical thinking skills, and create a meaningful construction—namely, a better understanding of what we read. What is it? A double-entry journal (also known as a two-sided or dialectical journal) allows us to record notes on one side of the page and to use the other side to comment on those notes. What kind of journal should I use? Make sure you find something you will use as you read. If you need something small, fine. If you want to write on loose-leaf sheets, fine. Whatever you use, make sure it's with you when you read. Rationale The main idea behind double-entry journals is that we retain more and we learn more deeply when we use metacognition, or reflecting on our thinking. The initial side of the journal allows us to get our thoughts down quickly, just as they occur. The other side of the journal allows us to step back from the initial thoughts and consider implications, connections, and further questions. We also learn more about our strengths and challenges as readers, scholars, and writers. As you read ... Listen to the questions and observations your mind makes as you read and capture those mind-noises on paper. Some things to note in your reading journal might be places in the text where you are confused, puzzled, or surprised struck by the language or an image can relate the text to something in your life or to another text or to something happening locally or globally can predict what might happen react strongly You may want to use one or more of these to help you create your notes: a paraphrase of a complex segment of text a possible explanation of a confusing material a main idea from the resource and why it is important a strong positive or negative reaction and an explanation of that reaction a reason for agreeing or disagreeing with the author/producer a comparison and/or contrast of a passage with another resource or with prior knowledge a prediction based on evidence from the resource a question generated as a result of reading, viewing, or hearing the resource a description of a personal experience that relates to the resource After you finish reading... Re-read your notes. On the other side of the page or the notebook, write down any answers you've found. Write down any thoughts, comments, or questions that jump into your mind as you re-read your initial notes. Follow your thoughts. Note things you might want to research or study further. Double Entry Journal Different Ways to Keep a Double Entry Journal Left Hand Side Right Hand Side Quotes from the text Visual commentary (drawings, visual analogies, doodles) Quotes from the text Written reactions, reflections, commentary, musings (“Hmmm…”) Quotes from the text Connections Text to text Text to Self Text to world Observations, details revealed by close reading Significance What the text says… Why the text says this… Questions: “I wonder why…” Possible answers: “Maybe because…” Quotes from texts Questions (Clarifying & Probing) Quotes from texts Social Questions (Race, class, gender inequalities) Quotes from texts Memories Quotes from texts Naming Literary or Persuasive (Rhetorical) Techniques Double Entry Journal Notes/Passage from Text/ Notes/Comments/Response Make sure to note page # and/or section #’s of notes for future reference. “Squeezing” the Text: Close Reading A close reading is a careful, thorough, sustained examination of the words that make up a text. You "read closely" in order to focus your attention on the actual words contained in the text. Close reading is the most important skill you need for any form of literary studies. It means paying close attention to what is printed on the page. A close reading uses short quotations (a few words or only one word) inside sentences that make an argument about the work itself (rather than an argument about your reactions, incidents in the author's life, or whether things today are different from or similar to the society depicted in the literary work) (Jerz). Example (from Jerz): The imagery in this passage helps turn the tone of the poem from victimization to anger. In addition to fire images, the overall language is completely stripped down to bare ugliness. In previous lines, the sordidness has been intermixed with cheerful euphemisms: the agonizing work is an "exquisite dance" (24); the trembling hands are "white gulls" (22); the cough is "gay" (25). But in these later lines, all aesthetically pleasing terms vanish, leaving "sweet and ...blood" (85), "naked... [and]...bony children" (89), and a "skeleton body" (95). Your thoughts evolve not from someone else's truth about the reading but from your own observations. The more closely you can observe, the more original and exact your ideas will be. Situate the text within the historical or literary context Gather, annotate, and analyze key quotations from the text Use textual evidence to support your claims. To do a close reading, you choose a specific passage and analyze it in fine detail, as if with a magnifying glass. You then comment on points of style and on your reactions as a reader. Close reading is important because it is the building block for larger analysis. (Wheeler). To begin your close reading, ask yourself several specific questions about the passage. The following questions are not a formula but a starting point for your own thoughts. When you arrive at some answers, you are ready to organize and write. You should organize your close reading like any other kind of essay, paragraph by paragraph. 1. Paraphrase in ordinary language: Read the passage and carefully paraphrase its meaning in ordinary language. Does your paraphrase resonate with other important themes or issues in the text? Does your passage merely recapitulate these other themes (hint: it probably doesn't) or does it change your understanding of them in some ways? Does the passage contest or undermine suppositions made elsewhere in the text? What's the significance of the contradiction? (Wheeler). 2. Use sticky notes - Take note of any and all points of interest in the text. If you've got a thesis in mind already, use several different color sticky notes, each for information relevant to a separate prong of your argument. This will make your life much easier when you go back to integrate your sources, particularly if you've got an extensive amount of text to cover (Essberger). 3. Ask questions I. First Impressions: What is the first thing you notice about the passage? What is the second thing? Do the two things you noticed complement each other? Or contradict each other? What mood does the passage create in you? Why? II. Vocabulary and Diction: Which words do you notice first? Why? How do the important words relate to one another? Do any words seem oddly used to you? Why? Do any words have double meanings? Do they have extra connotations? Look up any unfamiliar words. III. Discerning Patterns: Be aware of recurring techniques-both literary and rhetorical-which the author uses to illustrate a concept. Specific sorts of imagery, allusion, or dialogue, which seem to be similar or related inevitably, reveal a larger intention that can be made into an argument. Does an image here remind you of an image elsewhere in the book? Where? What's the connection? How might this image fit into the pattern of the book as a whole? Could this passage symbolize the entire work? Could this passage serve as a microcosm--a little picture--of what's taking place in the whole work? What is the sentence rhythm like? Short and choppy? Long and flowing? Does it build on itself or stay at an even pace? What is the style like? Look at the punctuation. Is there anything unusual about it? Is there any repetition within the passage? What is the effect of that repetition? How many types of writing are in the passage? (For example, narration, description, argument, dialogue, rhymed or alliterative poetry, etc.) Can you identify paradoxes in the author's thought or subject? What is left out or kept silent? What would you expect the author to talk about that the author avoided? IV. Point of View and Characterization: How does the passage make you react or think about any characters or events within the narrative? Are there colors, sounds, physical description that appeals to the senses? Does this imagery form a pattern? Why might the author have chosen that color, sound or physical description? Who speaks in the passage? To whom does he or she speak? Does the narrator have a limited or partial point of view? Or does the narrator appear to be omniscient, and he knows things the characters couldn't possibly know? (For example, omniscient narrators might mention future historical events, events taking place "off stage," the thoughts and feelings of multiple characters, and so on). V. Symbolism: Are there metaphors? What kinds? Is there one controlling metaphor? If not, how many different metaphors are there, and in what order do they occur? How might that be significant? How might objects represent something else? Do any of the objects, colors, animals, or plants appearing in the passage have traditional connotations or meaning? What about religious or biblical significance? If there are multiple symbols in the work, could we read the entire passage as having allegorical meaning beyond the literal level? (Wheeler). 4. Get down to the details - One of the most sophisticated close reading techniques you can incorporate into your work is an analysis of the multiple connotations of a specific word. Be aware of every single word the author uses. When you find one of particular literal definition in mind, see if the connotations of the other definitions can be applied to your idea (This is particularly true of Shakespeare). (Essberger). 5. Consider the source in relation to other texts - If something in the work reminds you of something else you've read, there's quite possibly a good reason why. Consider how your source is a response to or a continuation of other texts. Always be on the look out for Christ symbolism and Greek mythological allusions; both are fairly easy to spot and can be effectively analyzed in support of a particular interpretation. (Essberger). Now, and only now are you ready to begin your actual writing. If you find that what you had thought might be the theme of the work, and it doesn't "fit," you must then go back to step one and start over. This is a trial and error exercise. You learn by doing. (Patten). interest, literally look it up in the dictionary and consider how each and every definition might be applied to the text. Even if the author uses it with one different Levels of Attention Close reading can be seen as four separate levels of attention which we can bring to the text. Most normal people read without being aware of them, and employ all four simultaneously. The four levels or types of reading become progressively more complex. Linguistic - You pay especially close attention to the surface linguistic elements of the text - that is, to aspects of vocabulary, grammar, and syntax. You might also note such things as figures of speech or any other features which contribute to the writer's individual style. Semantic - You take account at a deeper level of what the words mean - that is, what information they yield up, what meanings they denote and connote. Structural - You note the possible relationships between words within the text and this might include items from either the linguistic or semantic types of reading. Cultural - You note the relationship of any elements of the text to things outside it. These might be other pieces of writing by the same author, or other writings of the same type by different writers. They might be items of social or cultural history or even other academic disciplines which might seem relevant, such as philosophy or psychology. Close reading is not a skill which can be developed to a sophisticated extent overnight. It requires a lot of practice in the various linguistic and literary disciplines involved - and it requires that you do a lot of reading. The good news is that most people already possess the skills required. They have acquired them automatically through being able to read - even though they haven't been conscious of doing so. This is rather like many other things which we learn unconsciously. After all, you don't need to know the names of your leg muscles in order to walk down the street. The four types of reading also represent increasingly complex and sophisticated phases in our scrutiny of the text. Linguistic reading is largely descriptive. We are noting what is in the text and naming its parts for possible use in the next stage of reading. Semantic reading is cognitive. That is, we need to understand what the words are telling us - both at a surface and maybe at an implicit level. Structural reading is analytic. We must assess, examine, sift, and judge a large number of items from within the text in their relationships to each other. Cultural reading is interpretive. We offer judgments on the work in its general relationship to a large body of cultural material outside it. (Johnson) Essberger, Josef. “Building Your Argument Part One: Close Readings.” EnglishClub.com. 12 May 2008. <http://www.englishclub.com/writing/college_term_papers/14.html>. Jerz, Dennis G. “Close Reading.” Seton Hill University. 12 May 2008 <http://jerz.setonhhill.edu/EL150/2008/close_reading.php>. Johnson, Roy. “What is Close Reading?” Mantex. 12 May 2008 <http://mantex.co.uk/samples/closeread.htm>. Patten, Dr. Janice E. “Steps for Close Reading or Explication de texte: Patterns, polarities, problems, paradigm, puzzles, perception.” The Literary Link. 12 May 2008 <http://theliterarylink.com/closereading.html>. Wheeler, Dr. L. Kip. “Close Reading of a Literary Passage.” Carson-Newman College. 12 May 2008 <http://web.cn.edu/kwheeler/reading_lit.html>. how to mark a book We pressed a thought into the wayside, planted an impression along the verge.- from "Marginalia" by Billy Collins From the looks of a lot of home libraries I've been in, it would be presumptuous of me to start right in with "how to mark a book." I might as well start in with "how to destroy your garden." Most people would never mark a book. Most people teach their children not to color in books. (I think that coloring books are meant to wean us of this habit. They're a kind of nicotine patch for preschoolers.) Schoolchildren must lug around books all day and read them, but they must never mark in them. At the end of the school year, students are fined if the books have marks. So we have a nation that equates marking in books with sin and shame. To most adults, I think, books are rarefied or holy, perhaps too holy to interact with. Books crouch on shelves like household gods, keeping ignorance at bay. A small library on a home's main floor may amount to a false front, a prop to give neighbors a certain impression of their host's intellectual life. Neighbors may get the idea that he holds a reservoir of learning that could pour out of his mouth at any twist of the conversation. But the presence of a book may have nothing to do with its impact on its owner. A lot of people never really get mad at a book. Few people ever ever throw a book, kiss a book, cry over a book, or reread a page in a book more than once or twice, if that. Some people never use a dictionary to find out what a big word in a book means. As a species, people don't interact with books much. I'm not suggesting that you mark every book you own, any more than I would suggest that my dog mark every tree he sniffs. But you should be free to mark up most books in the most worthwhile core of your collection. My dog has his favorites, and so should you. Why mark in a book? I may retort, Why blaze a trail through a forest? I like hiking in forests, but I'm a tenderfoot, and if I'm going to blaze a trail, I want to do it only once per forest. Marking in a book is a great idea if you have a dreaming idea of picking the book up again someday. It's funny how people and bookstores sell used books on Alibris.com and Amazon.com. The fewer the marks, the greater the price! This is backwards thinking, so take advantage of the bargains. People love the idea of a pristine forest, but wouldn't you compromise some of that pristine-ness for a well-marked trail if you wished to hike in that forest? I mark my books for three reasons. First, I mark books to create trails. If it's a good book, I may be back again to see things I missed the first time. If I have to reestablish a trail, I may be wasting some of my time on that second reading. If my subsequent readings resemble my first, I may not get the full benefit of what only subsequent readings offer. Summaries, graphic organizers, highlighted text, and comments are good things to add to a book for this purpose. Second, I mark my books to establish territory. (My dog and the trees again.) By the time I break in certain kinds of books, I've found out more about myself, perhaps, than about any facts or opinions the book offers. I collect quotes that support ideas that affect me. I put those quotes in my book's margins, and I refer to them in an index I sometimes have to create by hand. (Click here for an example of an index I put together for one of my core books.) In this marking process, the book becomes my territory. In fact, the book becomes part of me in some way. Finally, I mark my books to learn to write. My improvement in writing involves close readings of writers I admire. If I like something I read, I want to know how the writer did it. There are patterns in the use of nouns, pronouns, verbs and other parts of speech; there are patterns in syntax and in sentence variation; and there are patterns in sound devices, such as alliteration and assonance. I mark these with different symbols or colors, and I connect these dots. Patterns emerge, and style emerges from patterns. Here are some other resources for learning how to make a satisfying mess out of your books: "How to Mark a Book," an essay by Mortimer J. Adler "All Books are Coloring Books," a book review of The Art of Reading: a Handbook on Writing by Roger J. Ray and Ann Ray