Part II - Lesson 7-2 Human Suffering - William Cowper.doc

advertisement

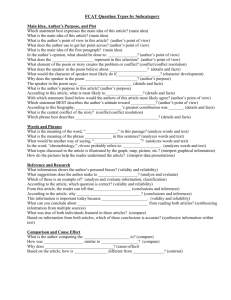

CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Seven – The Eighteenth Century (1770 – 1789) Lesson 7.2 – Human Suffering: William Cowper George Romney, William Cowper (1792) National Portrait Gallery, London Overview: This lesson examines another eighteenth-century poet, William Cowper, whose work is both deeply religious and highly emotive. His principal subject, in the following poems, is human suffering, a central Christian theme, which we discussed earlier in our reading of the Psalms. We will begin with “The Castaway,” a narrative based on a true story, which also seems to express Cowper’s own condition of mental illness, despair, deep loneliness, and resignation to his destructive end. Then, we will read Cowper’s Olney Hymns, which he composed while deeply influenced by the Evangelical preacher John Newton, a period of considerable fervor in the Evangelic movement. Cowper’s desire to overcome sin and to attain intimacy with God is expressed with deep emotion and vivid imagery; at times, too, we sense his very personal pain of severe mental illness. Objectives: To explore Cowper’s expression of profound individual suffering (that of others and his own) To identify the ways in which Cowper’s poems oscillate between expressions of loneliness and abandonment in the world, and assertions that salvation is found in God To consider how Cowper’s highly emotive poems anticipate the emphasis that will emerge more strongly in the Romantic period on the importance of subjectivity, human feeling, and the imaginative mind as a foundation for redemption in a fallen world To acknowledge how Cowper, in style and tone, anticipates William Blake Lesson 7.2 – Human Suffering: William Cowper ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 1 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Seven – The Eighteenth Century (1770 – 1789) Readings: “The Castaway” (1799) http://www.poetryfoundation.org/search/?q=castaway From Olney Hymns (1765 - 1773) “The Contrite Heart” (#9) “Jehovah our Righteousness” (#11) “The Shining Light” (#32) “The Waiting Soul” (#33) “Light Shining out of Darkness” (#68) http://www.theotherpages.org/poems/olney.html 7.2.1. Biography The poetry of William Cowper (1731 – 1800) is characterized by a distinctive emotional strain. It is quite unlike much 18th – century verse, including the polished, intellectual poetry of writers like Alexander Pope, who exemplified a Neoclassical concern for formal order and emotional restraint. Because of his impassioned poetry, Cowper was later admired by Romantic poets, especially William Wordsworth and S.T. Coleridge. Cowper’s emotional tone arises from two principal sources: his psychological instability, which caused immense personal suffering, and his deep Christian faith (and, later, lack of it). In 1763, Cowper tried to commit suicide. Following that incident, he was deeply troubled by his sinful act and saw himself as damned. He turned to religion for hope, forming a deep friendship John Newton, a form captain in the Atlantic slave trade who converted to evangelic Christianity and became a clergyman. Newtown’s repentance for his involvement in the atrocities of the slave trade is powerfully expressed in the now-famous poem (and hymn), “Amazing Grace,” in which recounts how he was divinely saved from that moral blight: Amazing grace! How sweet the sound! That saved a wretch like me! I once was lost, but now am found, Was blind, but now I see. (1-4) Cowper, too, found his spiritual home in the Evangelical Church. He collaborated with Newton to compose a series of poems, the Olney Hymns. (Cowper lived in Olney, Buckinghamshire from 1767 – 1786). In 1773, however, Cowper experienced another episode of depression and madness. This time, he felt cast out by God and he abandoned the church, a sentiment that Lesson 7.2 – Human Suffering: William Cowper ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 2 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Seven – The Eighteenth Century (1770 – 1789) underpins his most famous work, “The Castaway” (1779). Thereafter, he found comfort, instead, in gardening, walking, poetry, and his pets. Another important aspect of Cowper’s life was his support for the Abolitionist movement, which gained its first considerable momentum during the 1780s and 1790s, as Christians, parliamentarians, political thinkers, writers, artists, and women banded together to force England to terminate its involvement in the Atlantic Slave trade: its abduction of Africans from their homes, inhumane transportation of them to the West Indies, enforcement of unpaid labour on cotton and sugar plantations, and accumulation of enormous profits from the sale of these highly-sought commodities. Cowper was one of many poets, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (the first Abolitionist bill was passed in Parliament in 1807), who contributed anti-slavery poems to the growing movement. “The Negro’s Complaint” (1788) is a powerful poem, spoken by a fictional African slave who articulates the injustice of his condition. Cowper, then, as all of these works suggest, was a sensitive man: he felt his own pain and that of others, a condition that he mitigated, for a time, through his intense devotion to God. 7.2.2. Literary Analysis and Study Questions “The Castaway” (1799) http://www.poetryfoundation.org/search/?q=castaway 1. “The Castaway” a. Diction Be sure to consult the dictionary to define all of the words that are unfamiliar to you. Cowper uses diction that is characteristic of the 18th century, and not of our own era. Note these words, in particular. What does each mean? Perforce Succor Cask, coop, and cord Respite Descant Allayed Propitious Whelm b. The Form of the Poem The poem is narrative: it tells a story. o Trace the sequence of events: A ship is at sea in a fierce storm. One member on board is “washed headlong” into the water. The rest of the crew try to save him with their “cask,” “coop,” and “cord,” but to ensure their own safety, they must not Lesson 7.2 – Human Suffering: William Cowper ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 3 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Seven – The Eighteenth Century (1770 – 1789) linger in treacherous waters and chose, instead, a quick “flight” from the drowning man. He struggles to save himself, desperately “repelling” his “destiny,” but he is overcome by the “stifling wave” and sinks to his death. The poem is also lyric: it expresses a deeply personal, private emotion. o The poem does not end with its narrative completion, when the drowning man “sank” to his death (58). Rather, it continues with three more stanzas. These final stanzas turn to the speaker and his emotional response to the event. He is intimately connected to them—not, it seems, because he was on board the ship and saw the event, but because he somehow knows of the tale and sees its relationship to his own condition of “misery.” He feels compelled to “trace / Its semblance in another’s case,” which is his own. In fact, the poem begins with his confession that he is as much “a destined wretch” (3) as the drowning man whose story he goes on to tell. c. The Speaker The speaker, clearly, wants to memorialize a man lost at sea, whose experience would otherwise not be recorded. He simply disappears. The speaker/poet steps in to record an event that would otherwise be overlooked: his work will “immortalize the dead.” His motive, though, goes deeper. He says that “misery still delights to trace / Its semblance in another’s case.” The final stanza gives added significance to the story of the drowning man, by suggesting that the cause was not only the invincible storm but also God’s abandonment of his people. These aren’t feeling that we know to have been the drowning man’s; instead, they are the speaker’s feelings. His feeling of being abandoned by God is like the drowning man’s aloneness in the water when he is not rescued by the crew still on board the ship. The final stanza expresses the speaker’s suffering: he uses the storm, now, as a metaphor for his own drowning in life, without a caring God. o Read the final stanza carefully. The storm was not “allayed” (diminished) by a “divine voice”: God did not intervene; furthermore, He is reduced to an impersonal “voice,” and is not, in the speaker’s mind, a fully compassionate being. No “propitious” (favourable) “light” shone in the darkness: God did not illumine the chaos with evidence of His providence, or plan for order. Darkness (evil, suffering) triumphs, it seems, not light. Lesson 7.2 – Human Suffering: William Cowper ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 4 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Seven – The Eighteenth Century (1770 – 1789) No “aid,” from any divine intervention, occurs. Instead, a person is “snatched” from safety (the literal ship and spiritual guardianship). Every person dies “alone,” without the comfort of feeling God’s presence. o Think even more carefully about the last two lines. They puzzle us. How could the speaker’s wretchedness be greater than that of the drowning man? The speaker lives while the man at sea died. Is it self-indulgent for the speaker to say that his “gulfs” are deeper and his condition “rougher”? Is this self pity? Or: Is his pain so great—the pain of life with no meaning and with no conviction of God’s salvation—that dying would be a comfort? In that sense, the man who drowned is better off. He is “whelmed” (engulfed, submerged, crushed) day after day after day by his emotional and spiritual pain, while the drowned man is released. d. Psalms The poem invites us to think of the Psalms, specifically those that utter the speakers’ cries of pain: they describe a wretched difficulty (sickness, treachery, ostracism from a community, persecution, personal sin) and they call to God for help and pray for rescue. Often, the suffering is expressed in dramatic, even exaggerated, terms. o Look at Psalms 12 and 13, for example. While each begins with a piercing cry for help, and an impassioned plea “How long, O Lord?,” both ultimately turn to reassurance that, with time, God’s “promises” and “steadfast love” will prevail. However, notice the difference between the poem and the Psalms, in that the Psalmists, in spite of unbearable suffering, have not lost their faith in God. They remain loyal followers of God and anticipate rescue, even though they are victims of a serious affliction. The Psalm is a call to God—communication that is meaningful because God is present and does listen—even though the speaker is puzzled by the seeming abandonment. o Cowper’s poem, however, is not a petition to God: His “voice” is absent; He is not present to hear the call, much less respond. Instead, the poem asserts implacable aloneness: all “perish, each alone.” This is a devastating state of mind: to have no faith in a benevolent God that cares about his Creation. Perhaps, then, we can understand how the speaker’s suffering, in life, is “deeper” and “rougher” than the other man’s death at sea. Lesson 7.2 – Human Suffering: William Cowper ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 5 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Seven – The Eighteenth Century (1770 – 1789) e. Metaphor We could say, then, that Cowper uses the story of the storm as a metaphor for the speaker’s own condition: he compares the two states to illuminate their similarities. Think carefully about what those similarities are. Ultimately, though, Cowper sets the speaker’s psychological and spiritual turmoil above the natural storm, saying that it is ongoing and worse. 7.2.3. Analysis and Questions for Blackboard Discussion Analysis: Cowper uses the metaphor of a storm at sea to make familiar the speaker’s own state of mind (which is, autobiographically, also his own). That metaphor is not surprising, perhaps, for an English poet, in a country whose maritime history would be filled with countless adventures and shipwrecks at sea. Shortly, we will read S.T. Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” which offers a similar setting at sea. Among English painters, too, that subject is common. J.M.W. Turner, especially, during the early nineteenth century, depicted storms and shipwrecks often. In France, Théodore Géricault The Raft of the Medusa similarly portrays a disaster at sea, powerfully expressing the desperate human struggle to survive. Lesson 7.2 – Human Suffering: William Cowper ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 6 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Seven – The Eighteenth Century (1770 – 1789) Slaves Throwing the Dead and Dying Overboard, Typhoon Coming On J.M.W. Turner (1840) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Lesson 7.2 – Human Suffering: William Cowper ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 7 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Seven – The Eighteenth Century (1770 – 1789) Snow Storm: Steamboat off a Harbour's Mouth, J. M. W. Turner (1842), Tate Britain, London Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa (1819), Louvre, Paris Lesson 7.2 – Human Suffering: William Cowper ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 8 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Seven – The Eighteenth Century (1770 – 1789) Further Analysis: These three paintings, however, and others like them, are secular seascapes: they depict an atrocious incident of deliberately throwing slaves overboard (in order to claim insurance for their deaths); a ship lost in a blinding snowstorm; the abandonment of struggling survivors on a tiny raft following the sinking of a large French frigate, whose upper-class passengers saved themselves at the expense of these people. Cowper’s poem, however, equates abandonment at sea with God’s seeming absence. He gives his subject a Christian context, which is not implied, it seems, by these paintings. Questions for Discussion: Think, then, about the poem in relation to the Psalms. Do any of them use the perils at sea as a metaphor (or literal experience) for the Psalmist’s cry for help? One would think that the sea would be a rare setting for the Psalms, in a geographic region (unlike England and parts of Europe) where remoteness from, rather than proximity to, water was characteristic. Many of the 150 Psalms are attributed to King David, living in Judah. Question 1: Can you find, in the Psalms, images and/or settings that describe the sea in relation to the speaker’s suffering, either literally or as a metaphor? If so, what Psalms are they and how is the sea portrayed? Question 2: What other images and settings recur through the Psalms in relation to the Psalmist’s expression of suffering? Is desert/dryness/thirst, for example, a recurring image and setting? 7.2.4. Literary Analysis and Study Questions 2. Onley Hymns (1765 – 1773) Notice how these poems, written earlier in Cowper’s life than “The Castaway,” are different in tone. The speaker does address God, expecting Him to hear and respond; in this respect, they resemble the Psalms. Cowper experienced his first bout of madness in 1762; it was followed by a turn to evangelical Christianity for hope and salvation, the period during which these poems were written. When he descended into madness again in 1773, he subsequently abandoned the church, feeling that God had abandoned him. We will read 5 of the 68 hymns: “The Contrite Heart” (#9) “Jehovah our Righteousness” (#11) “The Shining Light” (#32) “The Waiting Soul” (#33) “Light Shining out of Darkness” (#68) Lesson 7.2 – Human Suffering: William Cowper ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 9 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Seven – The Eighteenth Century (1770 – 1789) http://www.theotherpages.org/poems/olney.html “The Contrite Heart” What does “contrite” mean? Does it signify a broken spirit? Is that what is acceptable to God because it enables interior renewal and a turn to God for help? (Pride, in contrast, assumes independence and no need for God.) A broken spirit is a sacrifice for God, enabling a newly enlivened spirit. A spirit that is repentant, that desires renewal? What is troubling the speaker? Does he want to love God more deeply? What is preventing that? Look carefully at the final stanza. What does the speaker request of God? Why does he ask for either rejoicing or aching? Why would either be better than his current state? One would think that he might want only rejoicing. Is he not feeling anything at all, in which case pain would be better, even, than numbness? Oh make this heart rejoice or ache; Decide this doubt for me; And if it be not broken, break -And heal it, if it be. “Jehovah our Righteousness” In this poem, too, the speaker desires a deeper relationship with God. Here, his sin obstructs that. The sin is not named, but we know, biographically, that Cowper felt great personal shame after this attempted suicide, an act that, he felt, would damn him in God’s eyes. Also, he refers here to pride—“self-applause”—suggesting, again, perhaps, the need for a contrite heart. To understand just how agonized the speaker is, look at the vivid images that are used: o “polluted,” “sin twines” and “slides,” “fountain of vile thoughts” that “overflows” o God’s goodness, in contrast, is a “holy flame” o Why does Cowper use these vivid images, which we can almost see? Why does he create such a striking contrast between the two? o What other images in the poem are particularly effective? “The Shining Light” This poem expresses a greater sense of hope than the preceding hymns. Still, the speaker’s faith that God’s goodness will prevail, and that he will be rescued from despair, is articulated as a fragile hope. Lesson 7.2 – Human Suffering: William Cowper ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 10 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Seven – The Eighteenth Century (1770 – 1789) o Notice the diction and the images: it is a “whisper” (not a shout), a “glimmering” (not a bright light), a “forerunner of the sun” (not yet dawn). These words and images are beautiful, but they suggest fragility and mystery—something not yet fully present or known. Is that the condition of hope and faith? Is it always elusive and never fully grasped or counted on? o However, other words in the poem do express greater conviction: certainty that “the pilgrim’s way” is visible before him, that “the rising day” will come, and that he will “run” to greet it. Light is the poem’s principal image, named in the title. What, then, do you think is the dominant tone in the poem: is it “terror” and “despair” or emerging hope and joy? Or both? “The Waiting Soul” God is associated with the south wind, “breathing,” and “blowing” on the speaker, and able to bring the fragrance of spices. The speaker, in contrast, is the north, feeling cold, feeble, and in thirst. o Why are these images used? Are they effective? o Does the speaker have hope? If so, how much? “Light Shining out of Darkness” This is Cowper’s final Olney Hymn, and one of the best, I think. It is a hymn of praise for God, rather than a petition to be saved, like the earlier ones. As the final work, it exemplifies a concluding confidence in God’s goodness, omnipotence, and wondrous mystery. o goodness: How is that suggested? Why is he “smiling”? How is he like a sweet “flower” and not the “bitter” “bud”? Does he have “mercy” and “blessings” in abundance, like rain bursting from clouds? o omnipotence: How do we know that he does act and is not helpless in relation to the world’s affairs, and that he cares for his creation? What does he “perform”? Does he have “designs” and “purposes.” Why are they not withheld but “unfold every hour”? o mystery: How is that expressed? Where does God reside? Do we know? In the sea, mines, clouds? In what way is God “his own interpreter”? o The speaker, now, is certain that God is all of these things: because he is good and omnipotent his ultimate mystery is not a disconcerting act of abandonment but evidence of something immeasurably great. Lesson 7.2 – Human Suffering: William Cowper ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 11 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Seven – The Eighteenth Century (1770 – 1789) Notice how, in this final hymn, the speaker does not address God, in a cry for help, but addresses the readers (us). The poem asks us to share in the speaker’s praise for God: it discourages “blind unbelief”; likewise, it counsels against seeking to “scan” or know God fully, which we cannot as humans. Instead, he exhorts patient faith that God’s plan will, with time, be made “plain.” The poem is a call to all Christians to believe in God’s ways. 7.2.5. Question for Blackboard Discussion Read Cowper’s other Olney Hymns. Select one (among those we did not discuss above) that you think is particularly good. Name it and tell the class what you think its strengths are. Lesson 7.2 – Human Suffering: William Cowper ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 12