Report on Uganda Visit - Imaging in Developing Countries

advertisement

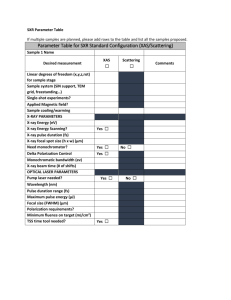

Report on Uganda Visit 13th – 22nd October 2004 Visit Aims and Rationale A visit was made to Kumi Hospital in Eastern Uganda by Andy Creeden, a member of the Imaging in Developing Countries Special Interest Group and Senior Radiographer, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust. The aim of the visit was evaluate the existing equipment and training within the x-ray department at Kumi Hospital and to determine how best the department could be supported by radiographers in the UK. This will ensure that any assistance provided will be appropriate for the needs of the department and be of maximum effectiveness in improving the service provided to patients. Whilst in Uganda a number of other hospitals were also visited in order to establish the health care context in which Kumi works and to investigate other potential avenues of support for radiography in Uganda. 1 Uganda Background Uganda lies between the Eastern and Western branches of the Great Rift Valley in Eastern Africa and occupies an area of 235,796 km2, which makes it similar in size to UK. In 2002 Uganda was found to have a population of approximately 24.6 million, 87% of whom live in rural areas. The annual national population growth rate is estimated at 3.5%. Kampala, the capital and only city in Uganda is home to 1.2 million people. At least 33 local languages are spoken in Uganda, with the most common being Luganda. English is the official language and is spoken as a second language by most educated Ugandans. Uganda has a gross domestic product (GDP) of US$5.8 billion, which equates to US$236 per capita (US$1989 purchasing power parity adjusted). In 2002 Uganda received US$638 in official development aid, but the economy is hampered by a large external debt estimated in 2000 to be around $3.3 billion. The economy is based for the most part on agriculture, accounting for 60% of the GDP, making it extremely vulnerable to fluctuations in commodity prices. A large proportion of the population are subsistence farmers who grow crops mainly for their own consumption. Major export crops include coffee, fish, tea and tobacco. The GDP per capita figure of US$236 does not give a true idea of normal income since the GDP is not equally divided; the richest 10% of people earn 15 times more than the poorest 10%. As a result 44% of people live below the national poverty line. Low national income goes some way to explaining Ugandas lack of development. Overall Uganda is ranked 146 (out of a total of 177 countries) on the United Nations table of Human Development Indicators. 31% of adults are illiterate and 48% of the population lack sustainable access to a safe water supply. Basic health indicators are also very poor. Life expectancy is only 45.7 years and over 14% of children die before their 5th birthday. Nearly 1 in 5 of the population are undernourished at any given time. There has been some success in reducing the spread of HIV/AIDS in recent years, nevertheless 4.1% of the population are HIV positive. Poor basic health indicators are exacerbated by low spending on healthcare, with just US$57 (purchasing parity adjusted) spent per person per year on all aspects of healthcare, and 5 doctors for every 100,000 people. This compares to US$1989 total healthcare spending per person and 164 doctors per 100,000 people in the UK. Since independence in 1962 Ugandas development and prosperity has been significantly undermined by civil and international war. However, whilst armed conflict continues between government and Lords Resistance Army forces in the North of the country, the majority of Uganda has enjoyed relative peace and stability over the past 15 years. A major problem continuing to face Uganda is power supply. All of the country’s electricity is generated by a single hydroelectric power station on the Nile as it leaves Lake Victoria. However, increasing demand and low poor rainfall over recent years has left water levels in Lake Victoria extremely low. The water that remains has had to be rationed and a system of ‘load shedding’ has been brought into operation whereby power supplies to various areas of the country are switched off for several hours at a time. Combined with an already unreliable distribution system, this makes the countrys’ electricity supply very unpredictable and this looks set to continue for the foreseeable future. 2 Kumi Hospital Contact Details Medical Superintendent: Address: Dr. John Opolot (+256 77 416 795) Kumi Hospital PO Box 9 Kumi UGANDA E-mail: kumihosp@africaonline.co.ug Getting to Kumi Hospital - - Taxis are available from airport to Entebbe for approximately 10,000 Ush (around £3.50). Minibus taxis from the main taxi park in Entebbe to the bus park in Entebbe run approximately every 15 minutes during the day and cost around 1,500 Ush. The post bus runs from Kampala to Mbale each day except Sunday. It leaves from outside the main post office on Kampala Road at 8am and takes around 6 hours. Tickets can be bought from the Private Boxes office on the Speke Road side of the building and cost 8000 Ush. Minibus taxis run throughout the day between Mbale (near the clocktower in the town centre) and Kumi. They take around an hour and cost 2500 Ush. A boda-boda (motorcycle or bicycle taxi) will take you the two or three miles between Kumi town and the hospital for 1500 Ush or a ‘special hire’ private taxi will charge around 3000 Ush. Hospital Background Kumi hospital was founded in 1929 as a leprosy colony and is located in the Teso region of Eastern Uganda close to the main road between Mbale and Soroti. Between 1986 and 1992 the Teso region, whose main economic activity was cattle trading, was devastated by both civil war and cattle rustling conducted by a hostile neighbouring nomadic tribe. The hospital was also affected, having its water supply destroyed and losing 2000 cattle from the hospital farm, and is still recovering from these troubles today. In 1997 the hospital transformed to a general hospital, with a capacity of 290 beds and specialising in the care of people with disabilities. The 8 wards consist of Surgical, Paediatrics, Male Medical, Female Medical, Maternity, Nutrition, Rehabilitation and Private and between them received 10,129 admissions during 2003. A large number of patients are also seen each day in the outpatient clinic. These services are supported by 2 operating theatres, a laboratory, an x-ray department, a dental department, a physiotherapy department and an orthopaedic workshop. The hospital currently has 215 staff including 4 doctors, 5 clinical officers (medical assistants), around 45 registered/enrolled nurses and 15 paramedical staff. The hospital operates as a Private Not for Profit Hospital (PNFP). It receives funding from a number of donors (particularly Leprosy Mission International and Chrisofell Blinden Mission)and the Ugandan Government. Patients are also required to make a small contibution towards the cost of some consultations, investigations and treatment. However, 3 due to the support of the donors, the hospital is able to offer a number of free services to the local community, and a number of other services at a reduced rate; Free Services: Leprosy management and care TB treatment Immunisation HIV counselling and testing Prevention of MTCT (Mother to Child Transmission) services Nutritional rehabilitation Blood transfusions VVF repair Reconstructive and rehabilitative services for disabled children Epilepsy treatment Antenatal care services Highly Subsidised: Cataract surgery Malaria treatment for under 5’s Normal deliveries All childrens ward admissions Very poor/very old patients Internally displaced persons The catchment population of Kumi hospital varies from 166,000 for primary health services to over 3 million for specialist services such as leprosy care and cataract surgery. Hospitals with neighbouring catchment areas include the governement hospitals at Atutur and Mbale and the PNFP Fredicar hospital. Kumi is able to refer patients beyond its capabilities to the government run Mulago National Referral Hospital in Kampala. Whilst treatment at government hospitals is technically free they frequently run out of medicines and supplies and patients have to buy them themselves from vendors at inflated prices. Staffing, hygiene and general quality of care is also often lower at government hospitals. Even the poorest patients therefore commonly prefer to pay a small fee for treatment at a PNFP hospital. Due to its relative proximity to the continuing armed resistance in the North of Uganda, the Teso region continues to receive a large number of refugees, known as internally displaced persons (IDP’s) from the conflict. In addition to their need for shelter, food and water these people also need access to health services, and this places an extra strain on the hospital. The greatest challenge facing the hospital is the absence of a piped water supply. This supply was destroyed around 15 years ago during the civil war and has not yet been rebuilt. Currently all water for the hospital and staff housing is extracted from bore holes and wells. This obviously impacts on Kumis ability to maintain a hygienic environment for patients. However it is hoped that the water supply will be restored within the next few years with the help of Australian aid. As discussed previously the electricity supply in Uganda is extremely unreliable, resulting in frequent power cuts and periods of low voltage supply. The hospital has a large generator, installed in the 1960s but unfortunately this was not working at the time of my visit and looked unlikely to be repaired in the foreseeable future. Presently during power cuts wards and departments have to cope without power, with the exception of the operating theatre which has a small petrol generator. As with most hospitals in Uganda, due to the extremely high patient to nurse ratio, basic nursing care of the patients in the hospital has to be carried out by relatives of the patient (generally referred to as the guardians). This releases the small number of nurses available for tasks such as changing dressings, dispensing drugs, keeping records and co-ordinating 4 investigations and procedures etc. Since Kumi may be many miles from the patients village and transport is scarce and costly, guardians normally stay with the patient at the hospital. Unfortunately there is no accommodation specifically for the use of guardians so most sleep alongside the patients bed on the ward or out in the open. In addition to IDP’s, the hospital provides treatment and care to a range of other disadvantaged groups. Although Uganda has had some success over recent years in combating HIV/AIDS there still remains a very high infection rate. Consequently the hospital treats a wide range of HIV related conditions, a disproportionate number of those affected being women. The hospital also offers maternity services to women, supporting national efforts to reduce the unacceptably high maternal death rates. Owing to its history, the hospital treats a large number of leprosy patients and this work has developed into more general help and support for those with physical disabilities, especially through the prosthetic workshop. The malnutrition unit cares for malnourished babies and children who are too sick to be cared for in the home. X-Ray Department Background The x-ray department at Kumi opened in 1973 with a Philips mobile x-ray unit donated from the Netherlands and a member of staff seconded from the medical records department. Previous to this patients were transferred to other hospitals for examinations. In 1998 a static GE unit was donated from the US giving the hospital 2 working units but in 2002 the x-ray tube on the Philips unit blew and is now uneconomical to repair. X-Ray Department Equipment The x-ray machine is a GE DXS 350 floor mounted x-ray unit. It was donated ‘second hand’ from the USA and installed in 1998 by engineers from Achilles, based in Kampala. Equipment details: Tube serial no. 591647 Tube model no. 11DB4 LBD serial no. 773652 LBD model no. 11FP6 CY60 AMP 1 LBD voltage 117v Whilst it was not possible to determine the age of this equipment it is estimated to be between 15 and 20 years old. It appears to be in reasonable working order except the electromagnetic locks and the light beam diaphragm (LBD). None of the electromagnetic locks work, and in practice the tube assembly is held in the correct longitudinal position with sandbags. The bulb in the LBD is absent, having been found to be not working at installation. A number of attempts have been made by the department staff to replace the bulb but to no avail. As a result, all exposures are made with the collimators fully open. In addition to the unnecessary radiation dose that this causes to the patient, the increased scatter leads to reduced image quality. The x-ray beam on this unit cannot be angled across the table for horizontal beam views of the hip, femur or tibia/fibula. The patient therefore has to be turned into position, sometimes despite significant trauma. The department also has no mobile x-ray unit and consequently patients have to be brought to the department regardless of their condition. The x-ray examination table was fixed height with a fixed top. Underneath was a PotterBucky tray, however this was not able to be connected to the x-ray generator. Consequently the grid did not oscillate and produced marked lines on films placed in the cassette tray. During my visit the grid assembly was removed from the bucky in order that, with difficulty, a cassette and a stationary grid could be placed in the film tray so that abdomen, spine and 5 pelvis films could be obtained without having to lift the patient to place the grid and cassette directly underneath. Whilst this did not produce results as good as might be expected from a working Potter-Bucky system it did represent a significant improvement. There are a reasonable of cassettes, although these are of varying age, type and condition. It was not possible to ascertain whether they are all the same speed but the staff appeared aware that different cassettes produced films that needed different amounts of time in the developer. The department has recently acquired a 43x43cm grid that is used in conjunction with all cassette sizes. It required a certain amount of practice to ensure that cassette, grid and x-ray beam were all aligned correctly, a task made more difficult with an uncooperative patient. There are few pieces of accessory equipment such as aspect markers, sandbags or foam pads. The staff have fashioned improvised aspect markers by cutting letter shapes out of lead sheets. No lead screen exists to protect staff whilst making exposures. In practice the radiographic staff wear a lead apron and stand as far back as the cable on the exposure switch allows. Unfortunately from this position it is not possible to observe the patient whilst the exposure is made. The lead apron appeared very tatty and worn but it was not possible to assess the integrity of the lead rubber inside. In order to permanently mark films with the patients name a home made ID marker is used. Although this doesn’t work as well as commercially available ID markers, it is remarkably effective. Films are processed manually and developed by inspection. The department staff are familiar with the idea of developing by time but since chemicals often have to used for more than a month and there is no replenisher available, the activity of the developer does not remain constant for a given temperature. In addition the department does not have a timing clock. As there is no running water at the hospital films are washed in standing water, which is changed daily. Whilst the department has a reasonable number of film hangers many of these, particularly the larger ones, are badly worn. As a result films are often only held at one corner during developing and can easily fall off or become stuck to others. The darkroom has a single safelight, which is in poor condition. The red film coating on the safelight filter has completely melted and cracked and has been replaced with cardboard. Luckily this appears to filter all wavelengths of light making the darkroom excessively dark rather than letting white light through and causing film fogging. In the absence of a film dryer, films are hung on a wooden rack and put outside to dry. This works very effectively on sunny days but obviously takes much longer when it is cold and wet. The films can also get quite dirty when there is a lot of dust blowing around. Availability of viewing boxes is limited to the x-ray department, OPD and operating theatre. Generally films are viewed by holding them up to the light. X-Ray Department Consumables and Supplies The x-ray department currently receives a single phase power supply. However a 3 phase supply enters the OPD building in which the x-ray equipment is situated and it would appear to be reasonably straightforward to extend the 3 phase supply as far as x-ray. In common with the rest of the country, the power supply to the x-ray department is very erratic. In 6 addition to total power cuts the department also experiences frequent ‘grey-outs’, (a drop in line voltage too large for the voltage stabilisers on the x-ray equipment to compensate for). In theory the x-ray department is supplied from the hospital emergency generators but at the time of my visit this was out of order and unlikely to be repaired in the foreseeable future. Consequently the x-ray department was out of action for a significant amount of time during my visit. Whilst the x-ray department has plumbing in place for a running water supply, the water supply to the hospital has not been in operation for a number of years. There are plans to reconnect this supply in the next couple of years. In the meantime water for washing films during processing and cleaning the department must be collected from one of the hospitals boreholes. X-ray film and processing chemicals are purchased from the government run Joint Medical Stores (JMS) in Kampala. A significant part of the government funding that the hospital receives is direct into its JMS account; as a result where items are available through JMS the hospital is almost obliged to purchase through them. Chemical supplies are usually fairly constant although the hospital budget only allows fresh chemicals to be mixed once a month. Film supplies through JMS are far less reliable and there are often nation-wide shortages of particular film sizes. On these occasions films are often ‘borrowed’ from neighbouring hospitals but collecting this film occupies a significant amount of staff time. In a short-term attempt to save money the hospital will often only buy certain sizes of film. In the long term however this results in increased film expenditure since inappropriate films have to be used (eg. fingers on 24x30cm or lumbar spines on 35x43cm). X-Ray Department Staff The department has 2 full time staff, Mr John Esunget and Mr James Oluka. Mr Esunget was working as the Senior Medical Records Assistant in 1973 when the Philips mobile unit was donated to the hospital. He showed an interest in radiography and was trained to perform basic examinations by a visiting Dutch doctor over a period of about 3 years, and has also received a short training placement at Mulago Referral Hospital in Kampala. Unfortunately however Mr Esunget is due to retire in the very near future. Mr Olaka undertook a 4-year diploma course in radiography qualifying in 1982 and coming to Kumi in 2001. He has also undertaken 8 months sonography training in Kampala. X-Ray Department Common Conditions The x-ray department receives referrals for most conditions and injuries that are commonly seen in the UK such as trauma, chest infections and joint pain. Motor vehicle trauma is particularly common, as are fractures in children. In addition there is a high prevalence of conditions not so frequently seen in the UK such as osteomyelitis, tuberculosis (often as a result of HIV infection) and longstanding uncorrected disabilities such as club foot. Due to the hospitals historical origin leprosy patients also make up a significant part of the workload. X-Ray Department Workload The department has a high workload by local standards and this has increased significantly over recent years. A slightly higher number of males than females were x-rayed in 2003; this is likely to be due to the fact that men are more likely to suffer trauma. X-rays of the chest and limbs make up the majority of the workload. Radiography of the axial skeleton is rarely performed due to the poor quality images produced and the lack of possible treatment options should pathology be identified. 7 Breakdown of Workload by Year Year 2001 2002 2003 No. of Patients X-Rayed 1214 1742 2302 Breakdown of 2003 Workload by Gender Gender Male Female No. of Patients X-Rayed 1348 954 Breakdown of 2003 Workload by Age Group Age Group Adults Children No. of Patients X-Rayed 1940 362 Breakdown of 2003 Workload by Referral Source Referral Source No. of Paitents X-Rayed Outpatients 1607 Inpatients 695 Breakdown of 2003 Workload by Body Part Body Part Skull Chest Abdomen Pelvis Spine Limbs Foreign Body Barium Study Other No. of Patients X-rayed 3.7% 41.1% 1.1% 7.3% 3.8% 42% 0.2% 0.54% 0.2% Consultations with Hospital Staff A wide range of hospital staff were consulted on the range and quality of services offered by the x-ray department. Many staff appeared to be happy with what was available. However it must be borne in mind that in Uganda it is not normally socially acceptable to directly criticise ones colleagues and that staff might have been concerned that complaints about the x-ray department might have been perceived as criticism of the radiographers. In addition many staff have limited experience of hospitals outside of Kumi and therefore have little to base their expectations on. Medical Superintendent – The medical superintendent was very supportive of any efforts to build the capacity of the x-ray department and was very helpful in answering questions about the running of the hospital, its services and background. He has experience of working with overseas supporters and the accountability they expect. He was keen to stress the very limited budget of the hospital and that any donated equipment must be affordable to run and maintain. Malnutrition ward – Clinical staff on the malnutrition ward were concerned about the quality of chest x-rays obtained for their patients. Chest x-rays are obtained routinely on admission to rule out tuberculosis (very common in malnourished children). Unfortunately films were 8 often rotated, of low contrast and had parts of the chest missed off. When repeats were requested these were often not much better. As a result clinical staff had difficulty in correctly diagnosing tuberculosis (sputum samples being particularly difficult to obtain from young children). Thus there was significant risk that patients might receive TB treatment when they didn’t have TB (a six-month course of tablets), or worse, not receive TB treatment when they did. The low standard of films appeared to be due to a combination of poor training, radiographers not being able to observe the patient whilst the exposure is being made, inability to collimate (no LBD bulb) and poor processing conditions. TB officer – The TB officer was generally happy with the quality of films he received. He was however concerned about the frequent disruptions to the service caused by power cuts and shortage of x-ray film. This resulted in a delay in starting treatment, and patients having to return at a later date to be x-rayed, often from a long distance away. OPD and orthopaedic clinical officers and doctors – clinical officers and doctors were generally able to diagnose gross pathology and trauma from the x-rays but were more challenged by more subtle conditions. This appeared to result from quality of training and experience of the clinical officers and doctors and the poor quality of the x-ray films. Two examples which presented whilst I was with them were a possible torus fracture of the wrist in a child and a possible neck of femur fracture in an elderly gentlemen. Both could have been diagnosed with much greater confidence had clearer x-rays been available. Conclusions and Recommendations Whilst the level of training of the staff working in the plain film x-ray department is a long way short of that in Western countries, it is adequate given the extremely limited resources available. During my visit I made a number of suggestions for minor improvements in techniques but I was not able to identify any significant ways in which the equipment that they had could be used better. If improved equipment were installed then further training for the staff would be needed. One of the existing staff is due to retire shortly and there is an urgent need to find a replacement. Qualified staff are very difficult to recruit in Uganda, particularly for hospitals in the PNFP sector. The best solution is probably to sponsor a local member of staff through a diploma in radiography, since a radiographer from the Kumi area is most likely to return to Kumi and remain loyal to the hospital. The cost of radiography training is estimated at around £300 per year for a total of 4 years. The hospital is greatly benefited by having a radiographer trained in ultrasound. However it is important to both continue to refresh and develop his skills and to train further staff in ultrasound techniques. A program to do this is currently being undertaken by the UK based charity OPT-IN. There is also a need to increase awareness around the appropriateness of referrals amongst both medical and radiographic staff. Skull and lumbar spine x-rays for instance are performed fairly regularly without any potential for alteration in management. Whilst this is a global problem it is a particular problem in an environment of such limited resources. The issue is likely best addressed through clinical staff Continuing Medical Education (CME), facilitated by support from overseas. It is important to ensure that effective use is made of overseas support. Several requests for assistance in obtaining books on radiography were made by hospital staff during my visit, for instance, despite a large box of donated radiography textbooks in one of the offices which had apparently remained largely untouched since it had arrived several months before. The hospital and donors together need to ensure that this kind of situation is not repeated. 9 In terms of equipment, a darkroom fed automatic processor would undoubtedly improve the quality of x-rays as well as reducing the time it takes to produce them. This would normally require a constant supply of running water which is unfortunately not currently available at the hospital. One solution might be a tabletop theatre type processor, some designs of which are able take their wash water from a refillable bottle. Using a theatre type processor would also overcome the problem of low throughput, which can result in unstable processing conditions in larger processors. Significant issues would still need to be addressed such as commitment by the hospital to the purchase of automatic processing chemicals (which cannot be ‘pushed’ in the same way as manual chemicals) and the financing of maintenance and repairs. Owing to the unpredictable electricity supply, consideration would have to be given to protecting the processor from power spikes with a voltage stabiliser or UPS. Nevertheless, an automatic processor has the potential to greatly enhance the quality of radiographs generated at Kumi. There are a number of other ways in which the x-ray department at Kumi could be helped in terms of equipment. These range from very inexpensive items to equipment that would cost thousands of pounds. Although very cheap to buy, assuming a suitable bulb could be found, a replacement LBD bulb could lead to a huge improvement in the diagnostic quality of the films produced. Positioning and centring could be done with much greater accuracy and collimation would reduce the scatter affecting the image as well as the radiation dose to the patient. There is also a significant amount of second hand equipment that could be collected in the UK and posted to the hospital at reasonable cost. This could include replacement cassettes, a 24x30cm secondary radiation grid, film hangers for manual processing, viewing boxes and anatomical markers. The current shift towards CR and DR in the UK is likely to result in a large number of cassettes and viewing boxes becoming available. Since the lead apron in the department looked old and could not be checked for internal damage it might also be helpful to check a second-hand apron in this country and also send it to Kumi. Although costing more, funding might also be sought for larger items of equipment that would also greatly enhance the capacity of Kumi’s x-ray department; The x-ray table was in a very poor state of repair and had no oscillating grid in the bucky. A replacement table would cost in the region of £800, but could be used with other units if an entire new x-ray unit were purchased in the future. A lead screen for the radiographers to stand behind whilst making exposures would not only improve radiation safety but also allow radiographers to watch the patient whilst the exposure is made, allowing better co-ordination in breath hold techniques. Mobile lead screens are available in Uganda for around £600 but it is likely that a double thickness brick wall coated in barium plaster would suffice for significantly lower cost. In the darkroom the safelight was next to useless, and had been repaired using a piece of cardboard. The safelight housing did not appear to be a modern type so the whole unit would probably need to be replaced instead of just the filter. In order to dry films quicker and reduce damage to them whilst they are drying one of the radiographers had produced diagrams and a budget for building a makeshift drying cabinet. The cost of the components was around £70. In the longer term a replacement static x-ray unit is required. The current unit has a large number of problems (faulty locks, unreliable exposures etc.) which cannot easily be remedied and it is unlikely that the x-ray tube will last for more than a couple of years. 10 Possibly even more useful than a replacement fixed unit would be a mobile x-ray unit. As well as allowing radiography on the wards it could act as a useful back-up for the fixed unit and supplement it by allowing horizontal beam lateral views. A mobile battery powered unit could also be used within the x-ray department during power cuts, helping to maintain the xray service without the need for a generator. Clearly x-ray units are exceptionally expensive. Replacing the current unit or buying a mobile would requite an exceptional level of funding, beyond the scope of conventional fundraising. Approaches and applications would therefore need to be made to appropriate grant making bodies and trusts for this kind of project. Radiographers in the UK are well placed to act as advocates in this process. 11 Mbale Government Hospital Mbale Government Hospital Mbale Government Hospital is a reasonably large regional referral hospital. No fees are charged to patients and little aid is received from donors. As a result the hospital suffers from regular shortages of drugs and consumables. X-ray Department The x-ray department employs a radiologist, a principal radiographer (Mr. Dan Wandera) and an assistant. The departments workload is low (around 10 patients per day) since there are 3 private clinics with x-ray facilities in Mbale. X-rays are taken using a Philips Practix mobile which is in good condition. Films are processed manually. Particular problems experienced by the department include the lack of any 35x35cm or 35x43cm cassettes (these film sizes are cut down in the darkroom to fit a 30x40cm cassette) and very old and badly damaged screens in the departments only 18x24 cassette. The department does not have a secondary radiation grid and, like Kumi, suffers from frequent shortages of film. The safelight in the darkroom is also in very poor condition. Given these challenges however, the department does produce some remarkably good quality radiographs. Conclusions and Recommendations A great deal of money could be spent increasing the capacity of the x-ray department at Mbale. However, given the relatively small workload of the department it is likely that any money could be better spent elsewhere. One notable exception to this might be the donation of a small selection of ‘second hand’ x-ray cassettes and possibly a secondary radiation grid; the relatively small cost of postage would likely result in significant improvements in image quality and thus improved diagnostic accuracy. 12 Mbale CURE Neurosurgical Hospital Mbale CURE Neurosurgical Hospital The hospital is fairly recently built and is heavily donor funded mainly by CURE USA. It specialises exclusively in paediatric neurosurgery with most patients suffering from hydrocephalus of varying aetiology. The ethos of the hospital appears to be to provide a relatively high standard of care to a small number of patients. X-Ray Department The x-ray department employs one radiographer and is visited one day per week by the radiologist from Mbale government hospital. The department consists of 1 fixed x-ray unit, 1 mobile unit, a CT scanner and an ultrasound system. Films are processed by a darkroom fed automatic processor. The departments radiographer appears well trained and the equipment is well maintained. The CT scanner has been installed within the last year and appears to be working well. Equipment in the department is serviced by engineers from Achilles (agents for Philips equipment) and Seimens, based in Kampala. Supplies of automatic processing chemistry, dry laser film etc. are also obtained through dealers in Kampala. Conclusions and Recommendations Whilst the x-ray department at CURE isn’t quite up to the standards of a Western department, it is significantly better than most others in Uganda. The department is well run and reasonably well resourced by donors in the US. Consequently little help is needed from the UK at this time. The department is however a good illustration of the standards that can be achieved within the constraints of a developing country. 13 Mulago National Referral Hospital Mulago National Referral Hospital Principle Radiographer: Philip Wegoye (Principle Radiographer) Address: Mulago National Referral Hospital PO Box 7051 Kampala UGANDA Mulago receives referrals from government and PNFP hospitals throughout Uganda and enjoys a strong reputation. Many patients choose not to be referred from the regions however due to the cost of reaching the capital from the regional centres and the reluctance of guardians to travel with them. The national School of Radiography is also located on the Mulago Hospital site. X-ray Department The x-ray department consists of 3 general x-ray rooms, a fluoroscopy room, a mammography unit, a mobile unit and 5 ultrasound rooms. Films are processed by a darkroom fed automatic processor. Much of the equipment is new thanks to a large recent donation from Japan. The department also has a teleradiology link to a local mental health facility, funded by donors from Canada. Staff appeared unclear about the purpose of the link, which was not in use due to the tubes in the digitisers at either end having blown and not been replaced. Conclusions and Recommendations Although the equipment donated from Japan might not be exactly what the radiographic staff themselves would have chosen, at least it is reasonably suitable and in good working order. The teleradiology project does not appear to have got off the ground yet, but this is not hampering the functioning of the x-ray department. Given that Mulago has the largest x-ray department in the country and is the site of the country’s only radiography training school, improving the knowledge and skills of the staff at Mulago would hopefully have the long term benefit of improving standards of radiography across Uganda. The staff seemed keen to update their knowledge and particularly asked for copies of Synergy to be sent out to them in order to help them keep abreast of recent developments. 14 Mbarara Government Hospital Mbarara Government Hospital Mbarara Government Hospital is, like Mbale, a regional referral hospital, covering a large area to the West of Kampala. The hospital is almost entirely funded by the government. X-ray Department The department is equipped with an Apelem fluoroscopy unit combined with an over-couch tube used for general radiography work. The department also owns an Apelem ‘Rafale’ mobile machine but this is out of action due to leaking capacitors. Usually films are processed using a darkroom fed automatic ‘Protec Compact 2’ processor but at the time I visited this was out of operation as a result of a burnt out drive motor. A ‘Sonodiagnost 250’ ultrasound scanner appeared to be in good working order but it appeared that there was no-one trained in its use. A further four scanners were found in ‘storage’ but it was not possible to ascertain their condition since the plugs had been removed and no-one appeared to know their origin. A ‘Picker IQ’ CT scanner was also found in storage, packed in a large shipping container. From what I could gather, this had been donated and shipped around 3 years ago by a Prespyrtarian Church in America but on arrival it was found to be missing an important part which apparently could not be replaced. I was unable to discover what this part was. Although the scanner was protected to some extent by its packaging the shipping container was full of dust which may well have damaged the equipment. A building, built from double thickness breeze-block, has been built to house the scanner. This appeared well designed and laid out but unfortunately did not contain any lead shielding. A 3-phase power supply was located close to the building. Conclusions and Recommendations The x-ray department appears reasonably well equipped and maintained, and the staff competent at plain film examinations. Although ultrasound equipment is available there does not appear to be anyone trained in its use. Given its wide potential application and low running cost ultrasound is an excellent technology for the African healthcare setting. Having a radiographer trained in ultrasound would bring significant benefits to the hospital and quality of care it can deliver. Medical staff at the hospital feel that having a working CT scanner would greatly enhance the options available to them in managing patients with acute head injuries; a very commonly seen condition. Being able to discover the site of bleed within the brain would allow surgeons to create burr holes in the skull and thus reduce the intracranial pressure. However, a number of challenges stand in the way of getting the scanner operational. Assuming the scanner is currently in good working order except for the missing part (and there is a strong chance that dust will have caused irreparable damage), suitably qualified engineers must be found to both install and maintain it. A suitable (and stable) power supply would need to found, as would a way of shielding scattered radiation. The scanner does not appear to have come with a method of hard-copying images so examinations would either need to be reported directly from the monitors or a method of hard-copy bought (and the 15 consumables funded). In addition staff would need to be allocated and trained to perform the scans, either by sending them to other hospitals in Uganda who already have scanners or by a radiographer visiting from outside the country. Given the significant hurdles involved in getting the current scanner running, the hospital management must decide if this is the course of action they wish to persue or whether the time, money and effort might be more effectively applied elsewhere. 16 References Uganda - The Bradt Guide (4th Ed), Philip Briggs Uganda – Oxfam Country Profile, Ian Leggett Human Development Report 2004, United Nations Kumi Hospital Annual Report 2003, Dr John Opolot 17